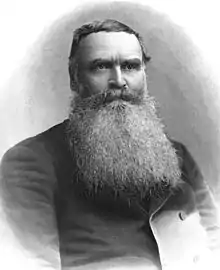

William Taylor | |

|---|---|

Bishop William Taylor | |

| Born | |

| Died | May 18, 1902 (aged 81) California, U.S. |

| Spouse | Isabelle Kimberlin |

| Parent(s) | Stuart Taylor and Martha Hickman |

William Taylor (1821–1902) was an American Missionary Bishop of the Methodist Episcopal Church, elected in 1884. Taylor University, a Christian college in Indiana, carries his name.

Ancestry and birth

Taylor was born May 2, 1821, in Rockbridge County—home to Sam Houston (born 1796), Robert E. Lee (born 1807), and Stonewall Jackson (born 1824)—in the Commonwealth of Virginia. He was the oldest of eleven children born to Stuart Taylor and Martha Hickman.[1] In his autobiography, Story of My Life (1896), Taylor describes his grandfather, James, as one of five brothers who were "Scotch-Irish of the Old Covenantor type…who emigrated from County Armagh, Ireland, to the colony of Virginia, about one hundred and thirty years ago" (i.e. 1766). The Hickman family was of English ancestry and settled in Delaware in the late 1750s. Both families "fought for American freedom in the Revolution of 1776" and afterward emancipated their slaves.[2] Taylor’s father, Stuart, was a "tanner and currier—a mechanical genius of his times"; his mother was "mistress of the manufacture of all kinds of cloth". Both parents, he says, were of "powerful constitution of body and mind…their English school education quite equal to the average of their day".[3]

Conversion to Christ

Before William was ten years old, his grandmother had taught him the Lord's Prayer and explained that he could become a son of God. He longed for this relationship, but was unsure how to obtain it. Overhearing the story of a poor Black man who had received salvation, he wondered why he could not, also. He recounts in his autobiography,

- "soon after, as I sat one night by the kitchen fire, the Spirit of the Lord came on me and I found myself suddenly weeping aloud and confessing my sins to God in detail, as I could recall them, and begged Him for Jesus' sake to forgive them, with all I could not remember; and I found myself trusting in Jesus that it would all be so, and in a few minutes my heart was filled with peace and love, not the shadow of a doubt remaining."

He entered the Baltimore Annual Conference in 1843. Bishop Taylor traveled to San Francisco, California, in 1849, and organized the first Methodist church in San Francisco. The 1860 edition of Address to Young America refers to him as "... of the California Conference." Taylor University was named after him and according to its website, he started the first hospital in California.

Missionary travels

Between 1856 and 1883, he traveled in many parts of the world as an evangelist. His vast missionary travels included Australia and South Africa (1863-1866); England, the West Indies, British Guiana, and Ceylon (1866-1870); India (1870-1875); South America (1875-1884); and Liberia, Angola, Congo, and Mozambique (1885-1896).[4] He was elected Missionary Bishop of Africa on May 22, 1884,[5] and retired in 1896 to California. His son Henry Reed Taylor was born in Cape Town became a pioneer ornithologist of California. As stated in his book "The Flaming Torch in Darkest Africa," the title of the work was adopted by the bishop according to the nickname given to him by the local community. In the introduction, written by Henry M. Stanley, it states, "The natives everywhere on the territories where his missionary work called him knew him as 'The Flaming Torch,' or 'Fire Stick,' as some might translate the Zulu word Isikunisivutayp."[6]

Criticism

Bishop Taylor was criticized by Robert Cust, Acting Secretary of the Royal Asiatic Society, writing in the introduction to Heli Chatelain's Grammatica Elementar du Kimbundu ou Lingua de Angola for conducting "Self-Supporting Missions" in Angola, implying that the poverty his leadership caused for his deacons resulted in the death of Dr. Summers at the Luluaburg mission on the Upper Kassai River, Angola. Nonetheless, the mission did produce the first modern grammar of Kimbundu, the national language of Angola. The "self-supporting mission" concept is not explained in Robert Cust's note, but he squarely identified himself as critical of Taylor's "missionary methods".[7]

Selected works

- Seven Years' Street Preaching in San Francisco (1857)

- Address to Young America, and a Word to the Old Folks (1857)

- Christian Adventures in South Africa (1867)

- Four Years' Campaign in India (1875)

- Our South American Cousins (1878)

- Ten Years of Self-Supporting Missions in India (1882)

- Story of My Life (1895)

- Flaming Torch in Darkest Africa (1898)

See also

- List of bishops of the United Methodist Church

- Justus Henry Nelson – Amazon missionary recruited by Taylor

- 100 McAllister Street – originally known as the William Taylor Hotel and Temple Methodist Episcopal Church

References

- ↑ Taylor 1896, p. 32.

- ↑ Taylor 1896, p. 25.

- ↑ Taylor 1896, p. 26.

- ↑ Lay, Robert F. "Lessons of Infinite Advantage: William Taylor's California Experiences." Lanham: The Scarecrow Press, 2010.

- ↑ Hunt, Rockwell D. (January 1950). California's Stately Hall of Fame. Stockton, California: College of the Pacific. p. 258.

- ↑ Taylor, William. "The Flaming Torch in Darkest Africa." New York: Eaton & Mains, 1898.

- ↑ Chatelain, H, Grammatica Elementar du Kimbundu ou Lingua de Angola, Charles Schuchardi, Genebra,1888-89 p.V-VII

- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Gilman, D. C.; Peck, H. T.; Colby, F. M., eds. (1905). New International Encyclopedia (1st ed.). New York: Dodd, Mead.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: Missing or empty|title=(help)

Sources

- Taylor, William (1896). John Clark Ridpath (ed.). Story of My Life: An Account of What I Have Thought and Said and Done in My Ministry of More than Fifty-Three Years in Christian Lands and Among the Heathen. Written by Myself. New York: Hunt & Eaton.

Further reading

- William C. Ringenberg, Taylor University: The First 150 Years (Upland IN: Taylor University Press, 1996) ISBN 0-9621187-2-9