| Van Orden v. Perry | |

|---|---|

| |

| Argued March 2, 2005 Decided June 27, 2005 | |

| Full case name | Thomas Van Orden v. Rick Perry, in his official capacity as Governor of Texas and Chairman, State Preservation Board, et al. |

| Docket no. | 03-1500 |

| Citations | 545 U.S. 677 (more) 125 S. Ct. 2854; 162 L. Ed. 2d 607; 2005 U.S. LEXIS 5215; 18 Fla. L. Weekly Fed. S 494 |

| Case history | |

| Prior | Judgment for defendant, 2002 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 26709 (W.D. Tex. Oct. 2, 2002); affirmed, 351 F.3d 173 (5th Cir. 2003); rehearing denied, 89 Fed. Appx. 905 (5th Cir. 2004); cert. granted, 543 U.S. 923 (2004). |

| Holding | |

| A Ten Commandments monument erected on the grounds of the Texas State Capitol did not violate the Establishment Clause, because the monument, when considered in context, conveyed a historic and social meaning rather than an intrusive religious endorsement. | |

| Court membership | |

| |

| Case opinions | |

| Plurality | Rehnquist, joined by Scalia, Kennedy, Thomas |

| Concurrence | Scalia |

| Concurrence | Thomas |

| Concurrence | Breyer (in judgment) |

| Dissent | Stevens, joined by Ginsburg |

| Dissent | O'Connor |

| Dissent | Souter, joined by Stevens, Ginsburg |

| Laws applied | |

| U.S. Const. amend. I | |

Van Orden v. Perry, 545 U.S. 677 (2005), is a United States Supreme Court case involving whether a display of the Ten Commandments on a monument given to the government at the Texas State Capitol in Austin violated the Establishment Clause of the First Amendment.

In a suit brought by Thomas Van Orden of Austin, the United States Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit ruled in November 2003 that the displays were constitutional, on the grounds that the monument conveyed both a religious and secular message. Van Orden appealed, and in October 2004 the high court agreed to hear the case at the same time as it heard McCreary County v. ACLU of Kentucky, a similar case challenging a display of the Ten Commandments at two county courthouses in Kentucky.

The appeal of the 5th Circuit's decision was argued by Erwin Chemerinsky, a constitutional law scholar and the Alston & Bird Professor of Law at Duke University School of Law, who represented Van Orden on a pro bono basis. Texas' case was argued by Texas Attorney General Greg Abbott. An amicus curiae was presented on behalf of the respondents (the state of Texas) by then-Solicitor General Paul Clement.

The Supreme Court ruled on June 27, 2005, by a vote of 5 to 4, that the display was constitutional. The Court chose not to employ the oft-used Lemon test in its analysis, reasoning that the display at issue was a "passive monument."[1] Instead, the Court looked to "the nature of the monument and ... our Nation's history."[1] Chief Justice William Rehnquist delivered the plurality opinion of the Court; Justice Stephen Breyer concurred in the judgment but wrote separately. The similar case of McCreary County v. ACLU of Kentucky was handed down the same day with the opposite result (also with a 5 to 4 decision). The "swing vote" in both cases was Breyer.

Background

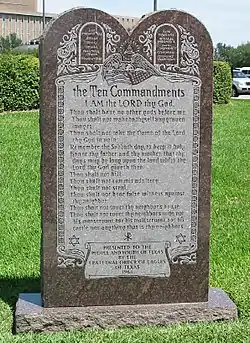

The monument under challenge was 6-feet high and 3-feet wide which was installed in 1961. It was donated to the State of Texas by the Fraternal Order of Eagles, a civic organization, which had received the support of Cecil B. DeMille, who had directed the film The Ten Commandments (1956).[2] The State accepted the monument and selected a site for it based on the recommendation of the state agency responsible for maintaining the Capitol grounds. The donating organization paid for its erection. Two state legislators presided over the dedication of the monument.

The monument was erected on the Capitol grounds, behind the capitol building (between the Texas Capitol and Supreme Court buildings). The surrounding 22 acres (89,000 m2) contained 17 monuments and 21 historical markers commemorating the "people, ideals, and events that compose Texan identity."

Plurality opinion

The plurality opinion stated that the monument was constitutional, as it represented historical value and not purely religious value. The primary content is the text of the Ten Commandments. An eagle grasping the American flag, an Eye of Providence, and two small tablets with what appears to be an ancient script are carved above the text of the Ten Commandments. Below the text are two Stars of David and the superimposed Greek letters Chi and Rho, which represent Christ. The bottom of the monument bears the inscription in capitals "Presented to the People and Youth of Texas by The Fraternal Order of Eagles of Texas 1961."

Thomas Van Orden challenged the constitutionality of the monument. A native Texan, Van Orden passed by the monument frequently when he would go to the Texas Supreme Court building to use its law library.

Breyer's concurrence

In opening his discussion of reasoning Breyer states:

The case before us is a borderline case. It concerns a large granite monument bearing the text of the Ten Commandments located on the grounds of the Texas State Capitol. On the one hand, the Commandments' text undeniably has a religious message, invoking, indeed emphasizing, the Deity. On the other hand, focusing on the text of the Commandments alone cannot conclusively resolve this case. Rather, to determine the message that the text here conveys, we must examine how the text is used. And that inquiry requires us to consider the context of the display.

Breyer continues to explain a position which seeks to balance between not "lead[ing] the law to exhibit a hostility toward religion that has no place in our Establishment Clause of the First Amendment traditions" and "recogniz[ing] the danger of the slippery slope" and ultimately rests upon a "matter of degree [which] is, I believe, critical in a borderline case such as this one."

Breyer concludes by stating he cannot agree with the plurality, nor with Justice Scalia's dissent in McCreary County v. ACLU of Kentucky, but while he does agree with Justice O'Connor's statement of principles in McCreary, he disagrees with her evaluation of the evidence as it bears on the applying those principles to Van Orden v. Perry.

Stevens' dissent

Stevens' dissenting opinion essentially stated that, in formulating a ruling for this case, the court had to consider whether the display had any significant relation to the specific and secular history of the state of Texas or the United States as a whole. Ultimately, Stevens asserted that the display "has no purported connection to God's role in the formation of Texas or the founding of our Nation" and therefore could not be protected on the basis that it was a display dealing with secular ideals. In fact, Stevens says that the display transmits the message that Texas specifically endorses the Judeo-Christian values of the display and thus violates the establishment clause.

See also

- List of United States Supreme Court cases, volume 545

- Stone v. Graham (1980)

- Glassroth v. Moore (11th Cir. 2003)

- McCreary County v. American Civil Liberties Union (2005)

- Pleasant Grove City v. Summum (2009)

- Green v. Haskell County Board of Commissioners (10th Cir. 2009)

References

- 1 2 "Van Orden v. Perry 545 U.S. 677 (2005)". Justia Law. Retrieved March 12, 2016.

- ↑ Greenhouse, Linda (February 28, 2005). "The Ten Commandments Reach the Supreme Court". The New York Times. Retrieved February 10, 2010.

Sources

- Van Orden v. Perry, oral arguments and opinions on Oyez.org

- U.S. Supreme Court docket for 03-1500 Van Orden v. Perry

- Van Orden v. Perry First Amendment Center online library (archived)

- Supreme Court on a Shoestring, Sylvia Moreno, The Washington Post, February 21, 2005

- Supreme Court splits on Ten Commandments, Warren Richey, Christian Science Monitor, June 28, 2005

External links

- Religion & Ethics Newsweekly (PBS), includes video coverage