.jpg.webp) The aircraft involved when still operated by American Airlines in 1998. | |

| Accident | |

|---|---|

| Date | 25 December 2003 |

| Summary | Failure to take off due to aircraft overload as a result of poor management |

| Site | Cotonou Airport, Cotonou, Benin 6°20′48.9″N 2°22′16.9″E / 6.346917°N 2.371361°E |

| Total fatalities | 141[note 1] |

| Total injuries | 23 |

| Aircraft | |

| Aircraft type | Boeing 727-223 |

| Operator | Union des Transports Africains de Guinée (UTA) |

| ICAO flight No. | GIH141 |

| Call sign | GULF INDIA HOTEL 141 |

| Registration | 3X-GDO |

| Flight origin | Conakry International Airport, Conakry, Guinea |

| 1st stopover | Cotonou Airport, Cotonou, Benin |

| 2nd stopover | Kufra Airport, Kufra, Libya |

| Last stopover | Beirut International Airport, Beirut, Lebanon |

| Destination | Dubai International Airport, Dubai, United Arab Emirates |

| Passengers | 150 |

| Crew | 10 |

| Fatalities | 138 |

| Injuries | 22 |

| Survivors | 22 |

| Ground casualties | |

| Ground fatalities | 3 |

| Ground injuries | 1 |

UTA Flight 141 was a scheduled international passenger flight operated by Guinean regional airline Union des Transports Africains de Guinée, flying from Conakry to Dubai with stopovers in Benin, Libya and Lebanon. On 25 December 2003, the Boeing 727–223 operating the flight struck a building and crashed into the Bight of Benin while rolling for take off from Cotonou, killing 141 people. The crash of Flight 141 was the deadliest crash in Benin's aviation history.[1][2]

The investigation concluded that the crash was primarily caused by overloading. However, it also subsequently revealed massive incompetence within the airline, particularly on its dangerous safety culture. The issue had gone unnoticed following lapses between authorities and further incompetence in management oversight led to the aircraft's overloaded state. Multiple factors, including the short runway at Cotonou and the high demand of passengers for the route, had also contributed to the crash.[3]

In regards to the result of the investigation, the Guinean government was urged to create reforms and regulations on the civil aviation authorities in the country. The BEA, the commission responsible for the investigation, had also urged ICAO to examine provisions related to safety oversight and the FAA and the European EASA were asked to support the creation of an autonomous weight and balance calculation system on board every airliner.[3]

Background

In the 20th century, most countries in West Africa did not have the capability to create and maintain a national airline. For decades, flight routes in West Africa were mainly served by Air Afrique, a transnational airline for Francophone West and Central Africa. It was once considered as one of the largest airlines in Africa and one of the most reputable.[4] However, after reports of mismanagement, corruption and the fallout of the aviation industry following the September 11 attacks, Air Afrique declared bankruptcy in 2002.[3]

In the aftermath of Air Afrique's demise, there were no more routes connecting major cities in West Africa and to other regions. The bankruptcy of Air Afrique caused isolation between the countries, despite their close geographical location. While Air Afrique's routes were immediately taken over by Air France, most of the flights were perceived as inconvenient. Such an example was a flight from Conakry to Cotonou, in which passengers had to fly to Paris first before they could continue to Cotonou. Immediately, there were high demands for new airlines to open more direct routes.[3]

As an attempt to fill the void that had been left by Air Afrique, multiple existing small airlines began to offer services to these major routes. Among them was Union des Transports Africains de Guinée (also known as UTA), a regional airliner that was operated by Lebanese people in Guinea.[3]

For years, the Lebanese diaspora was part of the backbone of the economic activity in multiple West African countries. Many Lebanese businessmen had forged robust relationship with government officials to sign contracts within West Africa's public infrastructure sectors. An example was cited on a CIA document from 1988, with the following quote explaining the economic situation in one of the West African countries:[5]

In Sierra Leone, the Lebanese have continued to dominate the country's destitute economy [...]. Throughout the 1970s and 1980s Jamil [Muhammad] helped prop up the regime of then President Stevens by obtaining rice and oil [...]. In return, Stevens turned a blind eye to Jamil's wide-scale business activities, allowing him to exercise relatively unchecked control over the lucrative diamond and fishing industries

— CIA, "The Lebanese in Sub-Saharan Africa: An Intelligence Assessment (1988)"[6]

However, the lack of direct flights to Lebanon caused dozens of Lebanese to board transit flights between multiple cities in West Africa. Lebanon's flag carrier, Middle East Airlines, previously had operated flight routes in West Africa and later decided to terminate the service.[3]

On 23 July 2003, the government of Benin granted temporary authorization for UTA to operate charter flights for Conakry – Cotonou – Beirut – Cotonou – Conakry route. The airline later requested clearance to operate another extension flight to Dubai, known for its duty-free shopping, possibly to amplify profitability. The request was later granted in November 2003.[3]

Aircraft

The aircraft was a Boeing 727-223. Manufactured in 1977 with a serial number of 21370, it was equipped with three Pratt & Whitney JT8D-9A engines. The aircraft was registered as N865AA and was delivered to American Airlines.[3]: 14–16

Throughout its operational history, the aircraft had been operated by multiple operators. From June 1977 to January 2003, the aircraft was owned by American Airlines. However, in October 2001 the aircraft was stored in California's Mojave Desert. It subsequently became the property of Wells Fargo Bank Northwest in October 2002.[3]: 14–16

In January 2003, the aircraft was sold to a Miami-based leasing company Financial Advisory Group (FAG). The aircraft was then delivered to Ariana Afghan Airlines following FAA authorization to operate a ferry flight to Kabul under a new registration of YA-FAK. The first leasing contract was signed by Swaziland's Alpha and Omega Airways and the aircraft subsequently changed its registration to 3D-FAK in June 2003. In October 2003, the aircraft was subleased by Alpha and Omega Airways to UTA and the aircraft was registered under Guinean registration of 3X-GDO.[3]: 14–16

The aircraft had undergone a total of 40,452 flight cycles. The last major C check, the highest category for an aircraft maintenance, was carried out in January 2001 by American Airlines. There were insufficient documents on modifications that had been made on the aircraft. It was described as "materially impossible" to obtain the appropriate documents of the aircraft during its operation with UTA.[3]: 14–16

Flight

Flight 141 was a chartered passenger flight from the Guinean capital of Conakry, Benin's largest city of Cotonou and the Lebanese capital of Beirut with a final destination in Dubai. A stopover was included in the flight plan with the Libyan town of Kufra as a refueling stop. It was a weekly scheduled flight with one round trip flight per week.[3]: 8

The aircraft had been chartered by 2 Lebanese men.[7] Many of those on board were Lebanese diaspora who had been living in multiple West African countries for years. As it was Christmas Day, many of those on board were travelling home to spend the holidays with families.[8][9] Dozens of passengers could be seen carrying hand baggage filled with Christmas gifts. The situation was chaotic as the check-in staff at the airport had not allocated seats for the passengers. A boarding pass was also not needed in the airport. Passengers could sell their respective seats at last-minute to someone else who were not booked on the flight as their names were not written on the boarding pass.[3]: 32, 35

The aircraft was full with passengers. A total of 86 people had boarded the aircraft in Conakry and 9 people had disembarked in Cotonou. The aircraft had also received another 10 passengers from an aircraft that had flown from Togo. The boarding was disorderly. Many passengers tried to sit beside their friends and even occupied the cabin jump seats and the cabin crew were overwhelmed. Meanwhile, the flight crew were involved in an argument inside the cockpit as they had not received the basic information on the aircraft's load.[3]: 8

| 13:37:38 | First Officer | The sheets they gave us don't have the load. What is that? Come on come on (...). |

| 13:37:45 | First Officer | The sheets they gave us don't have the weight, only passengers. |

| 13:37:47 | Captain | Don't worry, We have the passengers manifest, without weight. |

While the cockpit crew were engaged in an argument on the weight and balance, the ground baggage handler was loading the baggage at the aft of the aircraft. One of UTA's agents then asked the handler to load the baggage at the forward hold, which was already filled with baggage. Subsequently, the forward hold was full with baggage. Back in the cockpit, the crew continued to discuss on the weight of the baggage. They became more frustrated as there were no information regarding the number of passengers that had boarded the aircraft in Cotonou. It was a tense situation as all the flight crew were unable to determine the exact weight of the baggage of each passengers.[3]: 8

| 13:39:28 | Unknown | How many passengers on board?. Do you know how many passengers we (*)? |

| 13:39:40 | Captain | They didn't give us anything... fifty-five? Sixty five? How many? |

| 13:40:02 | Flight engineer | Fourteen. Up to us now to complete (*). |

| 13:40:02 | First Officer | But but but... that each of them is bringing on board the airplane a two hundred kilo suitcase.. two hundred kilos (that's not possible).. get them to unload them and weigh them! Then we will know, then there is no problem, then we can know where we are (*). |

As the Captain decided to discuss the matter with the flight engineer, the First Officer became angry and yelled at the Directorate General of UTA, who was sitting at the cockpit jump seat across him, due to the absence of information. The UTA executive, however, tried to reason with the First Officer on the matter.[3]: 77

| 13:46:17 | First Officer | You'll see (on this side) by the window. You will see when it takes off. We will see when the airplane takes off if we take off. (in angry tone) |

| 13:46:17 | First Officer | If we manage to take off... the people ... I tell you! It will be quite a performance if we manage to take off today! You will see if we manage to take off today, because at least let them put the exact weight so that we know it! Let them put the exact weight so that we can calculate it! |

| 13:46:44 | UTA executive | But the weight is indicated here! |

| 13:46:45 | First Officer | There is no weight... each passenger came on board with a twenty kilo bag. It's impossible you have an airplane with a hundred passengers! |

| 13:46:45 | First Officer | If this airplane takes off today, you will see, if this airplane takes off..(otherwise) we're going to ... we're going to drop into the sea. |

| 13:46:50 | First Officer | You will see when the aircraft will take off or we will crash on the sea. |

The UTA executive immediately apologized to the crew. He stated that he would tell the management off as soon as the aircraft arrive in Beirut, later added that he would send messages to not allow anymore baggage or luggage weighing more than 30 kilograms. By this time, all passengers had already boarded the aircraft. Fuel was added to both tanks and the flight plan had been filed by the captain. The Captain then configured the aircraft with flaps at 25 degrees. The elevator was set at 63⁄4 and full power with brakes on would be applied for the take-off, followed by a three-degree maximum for take-off climb. The First Officer was the pilot flying.[3]: 8

The air conditioner was shut down. The weather was hot and dry. Weather report stated that there were cirrus clouds covering the sky and that there were some stratocumulus at an altitude of 1,500 feet (460 m). The visibility was about 8 kilometres (5.0 mi; 4.3 nmi) and the humidity was at 75%.[3]: 17

As everything was set, the crew began the take-off roll. However, several passengers were still reluctant to sit down and decided to stand near their friends. This led the chief flight attendant to inform the cockpit crew on the situation. Order was finally restored after the Directorate General of UTA had called for order and the passengers finally decided to sit down on the floor.[3]: 8

| 13:58:18 | Captain | Let it off as if (*) take off your feet. |

| 13:58:20 | Captain | Take off your feet. |

| 13:58:21 | Captain | OK. |

| 13:58:23 | Captain | Bismillah el Rahman el Rahim (In the name of God, the most merciful and the most beneficial) |

At 13:58 local time, the flight crew applied take-off thrust. Few seconds later, the brakes were released. The First Officer was pushing the nose down and the captain was observing the airspeed. The aircraft then reached V1 and subsequently reached its VR speed. An input from 5-degree nose down to 10-degree nose up was made by the First Officer in a span of two seconds. The nose of the aircraft, however, remained constant and the speed continued to increase.[3]: 21

The Captain became anxious as the aircraft's wheel had not lifted off the runway. He then called for rotation at least twice. The First Officer then pulled the yoke even harder so the aircraft could take-off. The angle of attack then changed from −1.2-degree to a maximum of +9-degree, at a speed of 1 degree per second.[3]: 22

The aircraft finally managed to lift off at 13:59:07 for a negligible altitude. Realizing that they were going to run out of runway, the captain urged the first officer to pull harder.[3]: 22

| 13:59:02 | Captain | Rotate! Rotate! |

| 13:59:02 | Commentary | Noise followed by vibrations until impact |

| 13:59:03 | Captain | Rotate! |

| 13:59:06 | Captain | More! More! |

| 13:59:09 | Captain | Pull! (11x) |

| 13:59:11 | Commentary | Noise of impact |

| 13:59:14 | Commentary | End of recording |

At 13:59:11, the aircraft struck the localizer antennas at the end of the runway. The aircraft's main landing gears then impacted the localizer building, causing the roof to fly for approximately 9 meters from the point of impact. The right main landing gear then detached. The impact subsequently caused small parts of the tail and the aircraft's stair to detach as well. The aircraft then impacted the airport's concrete boundary fence, scraping the lower part of the fuselage and caused some parts of the flaps to separate from the wings.[3]: 23–26

The aircraft then slid and struck a rainwater drainage canal located right after the perimeter fence. The collision damaged the aircraft's landing gears and parts of its wings. The leading edge and the outer aileron from the right wing then separated from the airframe. A survivor who was seated at the rear of the aircraft stated that people flew off their seats and, at the moment of impact, "fly around the cabin". According to testimonies, some passengers had not attached their seatbelts.[3]: 26–27, 32

After it had struck the drainage canal, the aircraft broke up into three parts; the cockpit section, the fuselage, and the tail of the aircraft, all of which ended up in the sea. Majority of the fuselage managed to stay intact. However, the fuselage became upside down due to the impact, drowning the occupants inside. Those who were seated near the breaks were able to get out of the sinking wreckage.[3]: 28

Search and rescue

The crash was loud enough to be noticed by the two controllers in the tower. The fire brigade immediately arrived at the destroyed localizer building and later confirmed that a technician inside the building was seriously injured by the collision.[3]: 9 Members of the fire brigade then went down to the beach and found that the situation was already chaotic. Nearby beachgoers and residents had immediately flocked to the site. While some passengers managed to escape from the sinking wreckage, several others were still trapped inside the fuselage. According to CNN, several onlookers screamed as dead bodies washed on the beach. Several relatives of those on board even tried to recover the bodies of their next of kin by jumping onto the sea.[10][11]

The first hour of the rescue operation was difficult as the situation was hampered by thousands of onlookers on the crash site. Emergency crew could not execute their duties effectively. Some emergency vehicles even became stuck in the sand. Lack of coordination between rescue organizations further aggravated the situation.[3]: 32 The police had to use belts to push back onlookers.[12]

Benin's Health Minister Celine Segnon stated that at least 90 people had died due to the crash, while 18 people had survived.[13] Among them were the cockpit occupants. All except one of the people who were in the cockpit had managed to survive the crash. The First Officer was killed after his head had struck the right side of the cockpit during the impact. The search and rescue operation continued through the night as rescuers tried to recover more bodies and survivors. The nation's navy divers, army and Red Cross had been dispatched to assist in the rescue operation. Beninese President Mathieu Kérékou personally visited the crash site to observe the rescue operation.[11][14]

On 26 December, a Middle East Airlines plane carrying Lebanese Foreign Minister Jean Obeid and five army divers had arrived in Benin to assist with the rescue operation.[15][16] Rescuers, however, stated that it was unlikely to find anymore survivors from the crash site. Rescuers attempted to recover the wreckage by using chains that were tied onto tractors.[17] Meanwhile, both black boxes were recovered from the wreckage on 27 December.[18][19]

A total of 141 bodies had been recovered by the rescuers, 12 of whom could not be identified. Initially, there were 27 survivors at the crash site but 5 people later succumbed to their injuries. Additionally, the report listed 7 missing people.[20][3]: 9

Passengers and crews

According to Lebanese Foreign Minister Jean Obeid, over a hundred of those on board were Lebanese. There were also people from Togo, Guinea, Kenya, Libya, Sierra Leone, Palestine, Peru, Syria, Nigeria, and also a youth wrestler from Iran.[21][22] Among the passengers were 15 Bangladeshi UN peacekeepers returning from their duties in Sierra Leone and Liberia.[23][24] A congressional report from the United States Senate indicated that there were officials related to Hezbollah's West Africa operation on board Flight 141.[25]

The manifest indicated that a total of 86 people, including 4 children and 3 babies, boarded the aircraft while it was in Conakry. Among the 86 passengers were 45 passengers from Sierra Leone, including the Bangladeshi peacekeepers who had boarded without transit checks. In Cotonou, a total of 9 passengers disembarked from the aircraft and 63 people, including 3 children and 2 babies, boarded the aircraft. The aircraft also received 10 passengers, including a child and a baby, from a transit flight that had originated from Togo. Based on the written manifest, the total number of passengers were 150, consisted of 138 adults, 8 children and 6 babies. The exact number of passengers on board, however, were impossible to determine, as more passengers were thought to be aboard than were listed on the manifest.[3]: 7, 35

At the time of the accident, the aircraft was configured with 12 first-class seats, 138 economy seats, and 6 seats for flight attendants. There were five seats in the cockpit and 4 jump seats for the cabin crew.[3]: 12

All three flight crew members had previously flown for Libyan Arab Airlines, and had their first flight with the airline on 8 December 2003. All of the crew members were provided by Financial Advisory Group (FAG) as the owner of the aircraft. The captain was 49-year-old Najib Soleiman Al-Barouni[26] with 11,000 flight hours, including 8,000 hours on the Boeing 727. His commercial pilot license was issued by the United Kingdom in 1977. He later obtained the Boeing 727 flying license in 1988 and joined FAG in March 2003. Prior to his work with UTA, he had flown for Royal Jordanian Airlines for 3 months and Trans Air Benin for 6 months. The first officer was an unnamed 49-year-old male whose flight information was not stated in the accident report. He had obtained his commercial pilot license in 1979, issued by the United Kingdom. The flight engineer was an unnamed 45-year-old male who had 14,000 flight hours, all on the Boeing 727.[3]: 10–12

There were 7 other crew members on board the aircraft, consisted of four flight attendants, two ground mechanics and one transporter. There were also two UTA executives, including the Director General of UTA, aboard the aircraft. They were both seated at the cabin crew jump seats.[3]: 8, 12–13

Investigation

The crash was the deadliest civil airliner crash in the history of Benin. It was also the first major aircraft accident in the country. Thus, the country didn't have the experience to investigate the crash. While the government had set up a special commission to investigate the cause of the crash, the government requested the French BEA to carry out the probe. The investigation also invited representatives from Boeing and the FAA.[3]: 2, 37

According to the final report, the investigation team faced great difficulties during their attempts to obtain adequate data and documentations from UTA. The team had to rely to direct testimonies from the surviving crew members, reasonings, and calculations made from the available recorded parameters.[3]: 34

Weight and balance

Testimonies gathered from surviving passengers and crew members revealed that the crash might have been caused by the presence of a weight and balance problem. While investigators tried to examine this theory, they couldn't retrieve the supposed weight and balance data from UTA. There were no documents on the weight of the aircraft and the loading plan for the flight between Conakry and Cotonou. Investigators could only retrieve the passenger manifest and the weight of the hold baggage. The weight and balance sheets, all of which were from the previous owner Alpha Omega Airlines, were later provided by the Lebanese investigators.[3]: 33

The basic operating weight of the aircraft, the actual weight of the aircraft and its equipment without the weight of the fuel, was determined to be at around 43.5 to 47.17 tonnes (43,500 to 47,170 kg; 95,900 to 104,000 lb), with the latter being the most likely. The real weight of the passengers, however, was unknown. The weight of the baggage was also difficult to determine as UTA's check-in staffs had never limited the weight of the baggage to a specific weight. UTA's standard allowed weight per adult passenger was 75 kilograms (165 lb), although prior flights revealed weight variations between 75–84 kilograms (165–185 lb). The weight of the passengers and the baggage was later determined to be between 10,480 and 11,704 kilograms (23,104 and 25,803 lb).[3]: 34

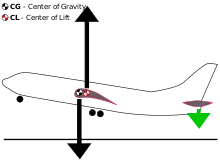

Calculation made by BEA, in addition with the aircraft's fuel and other loads, concluded that the take-off weight of Flight 141 was somewhere between 81,355 and 86,249 kilograms (179,357 and 190,146 lb). A simulation was then conducted, with an aircraft setting of flaps at 25-degree, stabilizer at 63⁄4 and a declared weight of 78 tonnes (78,000 kg; 172,000 lb). The simulation revealed that the aircraft's centre of gravity was still stable and balanced as the allowed centre of gravity was 19%. According to investigators, the aircraft would have managed to fly safely from the airport and shouldn't have crashed onto the localizer building at the end of the runway.[3]: 36–37

Failure to take-off

The calculation was inconsistent with testimonies that had been gathered from survivors of the crash, in which overloading had caused the crash of Flight 141. Further confirmation based on the recorded parameter was later conducted by Boeing and investigators. The calculation later revealed that the aircraft was actually 85.5 tonnes (85,500 kg; 188,000 lb) with a centre of gravity at 14%, much forward than the previous calculation. According to Boeing, with said calculation the aircraft would have required a much more rigorous and rapid input from the crew to pass the localizer building at the end of the runway.[3]: 38

The centre of gravity had significantly shifted to the front due to the improper loading by the baggage handler, later revealed that he never had a formal training, who had decided to load the already baggage-filled forward hold with more baggage rather than distributing the weight of the load properly. This was consistent with the recorded parameter, which showed the very slow response of the nose when the crew had tried to apply nose up input to the elevator.[3]: 37

With the centre of gravity value of 14%, the aircraft would have also required a greater setting of the stabilizer, which was at 73⁄4 rather than 63⁄4, for a much more effective take-off. By selecting the latter configuration, the aircraft would have taken off from the runway at a slower pace. The decision to select such configuration was caused by the crew's reliance over their past experience. As UTA had not provided the required data for the crew, they had to rely to the configuration that they had used in prior flights and thus assumed that the configuration of 63⁄4 for the stabilizer was sufficient enough for take-off, as it was usual to use the declared weight of 78 ton and the centre of gravity of 19% for the take-off calculation.[3]: 60

As the crew selected the configuration, the aircraft would have needed a longer distance to take-off from Cotonou. The situation was worsened by the fact that the scheduled time for take-off was at noon, in which temperature was at its peak. Available weather data showed that the temperature at the time was at 32 °C (90 °F). The hot temperature at the time would have caused air density to decrease, inhibiting the aircraft's ability to take-off. The shifted centre of gravity to the forward hold, combined with the insufficient configuration, the short runway and the hot temperature at the airport, caused the aircraft's failure to take-off from Cotonou.[3]: 38, 60

The operator

Prior to the operation of the Cotonou – Beirut route, UTA had been operating smaller routes in West Africa for years. The airline itself was a small regional airliner that was based in Guinea. It had relocated from its previous base in Sierra Leone from 1995 under the name West Coast. Before UTA managed to obtain Boeing 727, the airline had operated a Let L-410 Turbolet and an Antonov An-24 through a leasing contract. The Let L-410 was used for routes between multiple West African cities such as Freetown, Banjul and Abidjan, while the Antonov An-24 was used for mining companies and air ambulance.[3]: 44

The investigation revealed that all management posts in the airline had been filled with members of the same family with no knowledge whatsoever in aviation. The only non-family members in the airline was the technical director, who was responsible for the training, and the chief pilot, who was tasked on quality control, the latter was not competent enough for high capacity aircraft as he had not obtained the aircraft rating for Boeing 727.[3]: 46

UTA didn't possess sufficient documents of its own fleet. The first Boeing 727 that had been acquired by the airline was lacking in proper documentations which prompted the Lebanese investigators to not allow the aircraft to be operated under Lebanese registration as its essential documents somehow belonged to other foreign airlines. To rectify the problem, UTA bought another Boeing 727, the accident aircraft, from Alpha and Omega Airways. UTA also could not provide the maintenance and inspection manual to investigators. They also could not provide the operation manual. The manual had to be provided by the Guinean authorities. Further examination revealed that the manual had been copy-pasted from numerous foreign airlines. For example, some of the wordings had been copy-pasted from aircraft activities in Jordan and Gaza.[3]: 46–47

The following findings were also noted: the absence of work time limit for the flight crew, absence of details relating to loading, weight and balance of an aircraft, non-existent structure of the airline and even non-existent departments within the airline. UTA was also not able to provide, according to the final report, the slightest data on the flights that had been performed, flying hours and periods of service of the crew.[3]: 47

Investigator also noted the following declaration, found within UTA's document:[3]: 47

Safety is the most important rule for all airlines. This is an essential ingredient for any evaluation of success. This is the responsibility of all. Our objective is the effective mastery of disaster with zero accidents. The mastery of disasters means the prevention of injuries or accidents to persons or goods. With UTA, safety is the priority. Try to make it your attitude and rule of life

Oversight failure

Guinean authorities should have prevented the creation of UTA following the airline's blatant disregard to the required regulations that it should have followed. The decision to let UTA to operate flights in the region raised questions on the oversight. Furthermore, Guinean authorities somehow managed to immediately pass multiple controversial decisions made by UTA, such as the copy-pasted manual and the extension flight to Dubai, without proper examinations. The same issue could be applied to authorities in Swaziland.[3]: 57–58

Failing in oversights could be attributed to the environment of the country, in which adherence to regulations was often overlooked. The final report, however, stressed that multiple factors should also be considered, such as economic reasons and other variety of reasons, rather than blaming the authorities in Swaziland and Guinea. West Africa had been suffering endless conflicts and political instability for years. An immediate punishment on the struggling region over its non-compliance with the supposed regulations would have caused a negative feedback. Even though Guinean authorities had ratified the Chicago Convention, the implementation of it basically didn't exist. The international body that supervised the convention, ICAO, even stated in its 2001 report that Guinea had not established a regulatory mechanism on the country's aviation industry.[3]: 57–58

The final report revealed the unequal ability of countries to conduct evaluation on another country's adherence to the Chicago Convention. In response, ICAO was asked to actively help countries that were incapable of implementing aviation safety regulations to eventually develop a working system. A better transparency between countries that had ratified the convention was also ordered.[3]: 57–58

Conclusion

The final report was published in 2004.[27] The crash was mainly caused by overloading and the improper baggage loading of the Boeing 727. However, the investigation team also listed the structural causes that eventually enabled the overloading condition of the aircraft. The BEA listed the cause as the following:[3]: 62

The accident resulted from a direct cause:

- The difficulty that the flight crew encountered in performing the rotation with an overloaded airplane whose forward center of gravity was unknown to them;

and two structural causes:

- The operator’s serious lack of competence, organization and regulatory documentation, which made it impossible for it both to organize the operation of the route correctly and to check the loading of the airplane;

- The inadequacy of the supervision exercised by the Guinean civil aviation authorities and, previously, by the authorities in Swaziland, in the context of safety oversight.

— BEA

Following the accident, BEA issued recommendations to multiple international aviation bodies for better oversight of airliners within their scope of operation. The report also asked the United States FAA and Europe EASA to create an autonomous system for measuring weight and balance. Subsequently, all aircraft should be retrofitted with said system.[3]: 63–65

Aftermath

In response to the crash, the government of Benin declared three-days of national mourning.[28] The then United Nations Secretary General Kofi Annan expressed his condolences to the relatives of the crash, particularly to the families of the 15 UN peacekeepers.[29] United Nations Mission in Sierra Leone (UNAMSIL) later sent 11 members of a coordination team to Cotonou for the repatriation.[30] On 28 December, a repatriation ceremony was held in Cotonou for 77 Lebanese victims and 2 Iranians. A French military aircraft had been ordered to carry the coffins to Beirut. The aircraft arrived in Beirut on the next day and another repatriation ceremony was held, attended by Lebanese President Émile Lahoud, Prime Minister Rafic Hariri, Speaker of the House Nabih Berri and Muslim clerics.[31]

The crash of Flight 141 revealed another source of influx of cash for Hezbollah, a prominent Lebanese Shiite militant group, from countries in West Africa. Among the passengers was a Hezbollah official carrying US$2 million that had been raised by supporters of Hezbollah in West Africa. A report made by United States Congress revealed a vast network of wealthy Lebanese nationals in multiple West African countries who had supported Hezbollah campaigns and provided funds to the organization. The report further accused Hezbollah of blood diamond trade and other illicit activities with local drug traffickers in the region, which was already known for its notorious drug trafficking alliances.[25]

In October 2010, a Lebanese court sentenced the captain of the flight, Najib al-Barouni, to 20 years in prison after being found guilty of neglect. The court also sentenced Imad Saba, a Palestinian-American owner of the aircraft, UTA general manager Ahmed Khazem and UTA operations chief Mohammed Khazem to prison with serving time ranging from 3 months to 3 years. All of them were ordered to provide compensations with a total of US$930,000 to the relatives of the victims.[32]

See also

Notes

- ↑ According to the final report, a total of 138 people on board and 3 people on the ground were killed. The report, however, stated that there were doubts on the exact number.

References

- ↑ Ranter, Harro. "ASN Aircraft accident Boeing 727-223 3X-GDO Cotonou Airport (COO)". aviation-safety.net. Aviation Safety Network. Retrieved 17 October 2019.

- ↑ Ranter, Harro. "Benin air safety profile". aviation-safety.net. Aviation Safety Network. Retrieved 17 October 2019.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 51 "Final report Accident on 25 December 2003 at Cotonou Cadjèhoun aerodrome (Benin) to the Boeing 727-223 registered 3X-GDO operated by UTA (Union des Transports Africains)" (PDF). www.bea.aero. Bureau of Enquiry and Analysis for Civil Aviation Safety. Archived (PDF) from the original on 21 July 2011. Retrieved 9 June 2009.

- ↑ French, Howard W. (17 December 1995). "In Africa, Many National Airlines Fly on a Wing and a Prayer". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 21 June 2014.

- ↑ Levy, Dan (12 March 2013). Hezbollah's Fundraising Activity in Africa Focus on the Democratic Republic of Congo (PDF). International Institute for Counter-Terrorism. Retrieved 22 December 2021.

- ↑ The Lebanese in Sub-Saharan Africa: An Intelligence Assessment. Directorate of Intelligence Agency. January 1988.

- ↑ "Plane crash in Benin kills at least 111". CBC News. CBC. 26 December 2003. Retrieved 24 December 2021.

- ↑ Ahissou, Virgile. "More Than 60 Die in W. Africa Plane Crash". Associated Press. Retrieved 24 December 2021.

- ↑ "Airliner crash kills 135 in Benin". BBC News. BBC. 26 December 2003. Retrieved 24 December 2021.

- ↑ "Benin plane crash toll rises to 113". Al Jazeera. Retrieved 24 December 2021.

- 1 2 "Plane crashes on coast of Benin". CNN. Retrieved 24 December 2021.

- ↑ Karouny, Mariam (27 December 2003). "Rescuers Struggle To Find Bodies In Benin Plane Crash". Arab News. Retrieved 24 December 2021.

- ↑ "At least 90 dead in Cotonou plane crash, 31 survivors". The New Humanitarian. 26 December 2003. Retrieved 24 December 2021.

- ↑ "At least 24 survive plane crash in Africa". Tampa Bay Times. Retrieved 24 December 2021.

- ↑ "Lebanese Divers Search Sea for Victims of Benin Plane Crash". The New York Times. Agence France-Presse. 27 December 2003. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 24 December 2021.

- ↑ "Benin plane crash toll hits 135". UPI. Retrieved 24 December 2021.

- ↑ "Search goes on for Benin air crash survivors". The Guardian. 26 December 2003. Retrieved 24 December 2021.

- ↑ "African plane crash kills 90". ABC News. Australian Broadcasting Corporation. 25 December 2003. Retrieved 24 December 2021.

- ↑ "Black box from Benin plane crash found". ABC News. Australian Broadcasting Corporation. 26 December 2003. Retrieved 24 December 2021.

- ↑ "Divers drag bodies from plane crash". independent.ie. Retrieved 24 December 2021.

- ↑ "Survivors of Benin crash arrive home". ABC. 27 December 2003.

- ↑ "UN troops killed in Benin crash, nearly 140 killed". China Daily. Retrieved 24 December 2021.

- ↑ "Benin air crash dead flown home". BBC News. BBC. 29 December 2003.

- ↑ "15 BD troops killed in plane crash". Dawn. 28 December 2003. Retrieved 24 December 2021.

- 1 2 Confronting Drug Trafficking in West Africa: Hearing Before the Subcommittee on African Affairs of the Committee of Foreign Relations. The University of Michigan Documents Center: United States Senate Committee on Foreign Relations. 2009.

- ↑ Nasser, Cilina (9 January 2004). "Crashes raise doubts about airline safety". The Daily Star. Archived from the original on 12 January 2021. Retrieved 10 January 2021.

- ↑ "Huge cargo blamed for Benin crash". BBC. 27 March 2004. Retrieved 28 December 2021.

- ↑ "Bodies of Benin Plane Crash Victims Returned Home to Lebanon". VOA News. Retrieved 24 December 2021.

- ↑ "Annan Mourns Those Killed in Benin Air Crash, including Bangladeshi Peacekeepers". UN News. 29 December 2003. Retrieved 24 December 2021.

- ↑ "15 UNAMSIL peacekeepers die in plane crash in Benin Republic". reliefweb. Retrieved 24 December 2021.

- ↑ "Lebanese victims of Benin plane crash arrive home". CNN. Retrieved 24 December 2021.

- ↑ "Pilot, Airline Official Get 20 Years in Jail over Fatal Cotonou Crash". Naharnet. 27 October 2010. Retrieved 22 December 2021.

External links

- Accident description at the Aviation Safety Network (Summary of the French accident investigation)

- Cockpit Voice Recorder transcript and accident summary

- Bureau of Enquiry and Analysis for Civil Aviation Safety

- "Accident d'un Boeing 727 à Cotonou le 25 décembre 2003." (in French) (Archive)

- Summary of the English translation of investigation (Archive)

- Original French report (in French) (HTML) (Archive)

- PDF version of the French report (in French) (Archive)

- Pictures of the crash by BBC

- Photo of the accident aircraft by Aviation Safety Network