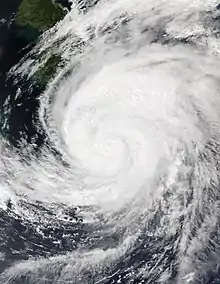

.jpg.webp) Nanmadol at peak intensity on September 16 | |

| Meteorological history | |

|---|---|

| Formed | September 9, 2022 |

| Extratropical | September 19, 2022 |

| Dissipated | September 20, 2022 |

| Violent typhoon | |

| 10-minute sustained (JMA) | |

| Highest winds | 195 km/h (120 mph) |

| Lowest pressure | 910 hPa (mbar); 26.87 inHg |

| Category 4-equivalent super typhoon | |

| 1-minute sustained (SSHWS/JTWC) | |

| Highest winds | 250 km/h (155 mph) |

| Lowest pressure | 916 hPa (mbar); 27.05 inHg |

| Overall effects | |

| Fatalities | 5 total |

| Damage | $1.2 billion (2022 USD) |

| Areas affected | Japan, South Korea, Philippines |

| IBTrACS / [1] | |

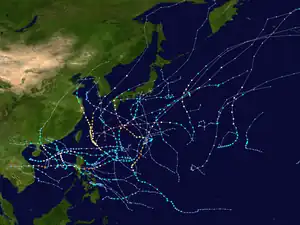

Part of the 2022 Pacific typhoon season | |

Typhoon Nanmadol, known in the Philippines as Super Typhoon Josie, was a powerful tropical cyclone that impacted Japan. The fourteenth named storm, seventh typhoon, and second super typhoon of the 2022 Pacific typhoon season and the most intense tropical cyclone worldwide in 2022, Nanmadol originated from a disturbance to the east of Iwo Jima which the Joint Typhoon Warning Center (JTWC) designated as a tropical depression on September 12. Later that same day, upon attaining tropical storm strength, it was named Nanmadol by the Japan Meteorological Agency (JMA).

The storm gradually became better organized, with its sustained winds reaching typhoon strength two days later. It then underwent rapid intensification, with its wind speed increasing by 45 km/h (30 mph). Nanmadol peaked with winds of 195 km/h (120 mph) and a central pressure of 910 mbar (26.87 inHg) on September 17, and also briefly entered the Philippine Area of Responsibility, where it received the name Josie. Following peak intensity, the storm began an eyewall replacement cycle and tracked north towards Japan, where it made landfall on Southern Kyushu on September 18. Later, Nanmadol became a severe tropical storm on September 19, before transitioning into an extratropical low early the next day.

In preparation for the storm, more than half a million people were evacuated in Japan, a rare "special warning" was issued for Kagoshima by the JMA.[2] In Kagoshima, 8,000 fled their homes, with another 12,000 in evacuation shelters. In South Korea, 7,000 households also experienced power outages.[3] Four deaths were attributed to Nanmadol, all in Japan, and more than 115 people were injured, with most just being minor injuries.[4]

Meteorological history

Tropical storm (39–73 mph, 63–118 km/h)

Category 1 (74–95 mph, 119–153 km/h)

Category 2 (96–110 mph, 154–177 km/h)

Category 3 (111–129 mph, 178–208 km/h)

Category 4 (130–156 mph, 209–251 km/h)

Category 5 (≥157 mph, ≥252 km/h)

Unknown

The origins of Typhoon Nanmadol can be traced back to an area of disturbed weather on September 9.[5] The disturbance favorable for development, being offset by warm sea surface temperatures of around 29–30 °C (84–86 °F).[5] A tropical depression developed, according to the Japan Meteorological Agency (JMA).[6] Satellite imagery revealed an obscure low-level circulation center.[5] Microwave imaging indicated a low-level circulation with a deep convection.[7] Formative banding blossomed around the disturbance and a LLC appeared on Himawari 8.[8] At 02:00 UTC on September 12, the United States Joint Typhoon Warning Center (JTWC) issued a Tropical Cyclone Formation Alert to the disturbance.[9] Later around the same day, the JTWC initiated advisories on the system and classified it as Tropical Depression 16W.[10] A broad low-level circulation with a disorganized over its convective.[11]

Six hours later, the JMA and the JTWC upgraded the system to a tropical storm, with the JMA assigning the name Nanmadol (2214) for the system.[12][13] The low-level banding wrapped in the deepening LLC.[14] Nanmadol quickly intensified, and was upgraded to a severe tropical storm by the JMA on September 14.[15] Microwave imaging revealed a well-defined banding feeder from the north and south on the storm's quadrants.[16] Early the next day, the JTWC upgraded Nanmadol to a Category 1-equivalent typhoon, approximately 578 nautical miles (1,070 km; 665 mi) east-southeast of Kadena Air Base.[17] Convective banding and a ragged eye formed.[17] Similarly, the JMA further upgraded Nanmadol to a typhoon.[18] A central convection had dense, along with having colder convective tops.[19]

Nanmadol strengthened to a Category 2-equivalent typhoon after the inner core became more organized.[20] On September 16, the storm became a Category 3-equivalent typhoon and an eye that was trying to cleared out.[21] Then, it rapidly strengthened into a Category 4-equivalent typhoon as it maintained a 15 nautical miles (28 km; 17 mi) sharply-outlined eye around the eyewall.[22] At around 15:00 UTC, the JTWC classified Nanmadol as a super typhoon.[23]

The JMA estimating a minimum central pressure of 910 hPa (26.87 inHg).[24] Nanmadol entered the Philippine Area of Responsibility, and was named Josie before eventually exiting 5 hours later.[25] Multispectral animated satellite imagery revealed a 21 nautical miles (39 km; 24 mi) surrounded eye around a deep convection.[26] The next day, Nanmadol weakened back to a Category 4-equivalent typhoon.[27] Satellite imagery revealed a rapid weakening on the system.[28] At 03:00 UTC on September 18, the JTWC further downgraded it to a Category 3-equivalent typhoon.[29] Nanmadol weakened further into a Category 2-equivalent typhoon as its structural strength began to rapidly deteriorate.[30] Nanmadol's were estimated at just 150 km/h (90 mph), which made it a Category 1-equivalent typhoon and made landfall over Southern Kyushu and a second landfall just south of Kagoshima around 18:00 UTC.[31][32] At 00:00 UTC on September 19, the JMA downgraded Nanmadol to a severe tropical storm.[33] The JTWC followed suit later that day, and declaring it tropical storm.[34] Satellite imagery revealed a swallowing convection shearing in the northeastwards.[35] At 21:00 UTC that day, the JTWC issued their final warning on the system.[36] The JMA issued its last advisory on Nanmadol, and declared it an extratropical low on September 20.[37]

Preparations and Impact

Japan

.jpg.webp)

Nanmadol was forecasted to be among the top five strongest typhoons to hit Japan.[38] It was also predicted to interact with a jet stream, enhancing the risk of already concerning flooding.[39] A rare special warning was issued for Kagoshima by the JMA; before Nanmadol, these warnings were never issued outside of Okinawa. Japan Airlines and All Nippon Airways cancelled 700 flights,[40] and train services experienced severe delays.[2] Areas affected by Typhoon Hinnamnor two weeks prior were also anticipated to be under Nanmadol's influence.[41] Overall, nearly 7 million people were ordered to evacuate as the storm approached.<re f>AFP (2022-09-18). "Rare 'special warning' issued as violent typhoon makes landfall in Japan". the Guardian. Archived from the original on 2022-09-18. Retrieved 2022-09-19.</ref> Of those 7 million, at least 965,000 were in Miyazaki, Kagoshima, and Amakusa. The highest alert on Japan's warning scale, level five, was issued for the city of Nishinoomote.[42]

Throughout the afternoon of September 18, Miyazaki saw over 15 inches of rain (381 mm) fall, where the JMA noted it was "raining like never before". Power lines were downed across affected areas, and at least 190,000 had experienced power outages[43] as Nanmadol passed. In Kagoshima, over 8,000 fled their homes with another 12,000 in evacuation shelters. Prime Minister Fumio Kishida mobilized police, firefighters, self-defense forces and another authorities in affected regions.[44] Several rivers in four prefectures, Kagoshima, Oita, Miyazaki and Kumamoto, went above flood risk levels. 100 dams were pre-discharged to prevent flooding, a higher number than the 76 discharged for Typhoon Haishen.[45] From September 15 to 19, 935 mm (36.8 in) of rainfall fell in Minamigo, and 784 mm (30.9 in) in Morozuka Village, and 669 mm (26.3 in) in Tojo City.[46]

At least 114 people were injured as Nanmadol passed.[47] At least most injuries were minor.[4] A crane from a construction site in Koryo-ocho had broken and nearly fell. Trees were fallen in affected areas, and many houses were damaged, injuring many residents in cities. Cars were trapped in roads due to flooding, and some people had to climb to the roof of their vehicles. A landslide in Tojo city left a road impassable. A nursing home was flooded in Nobeoka city, and temporary shelter buildings were blown away in Miyazaki city. In the latter city's prefecture, a month's worth of rain was dumped in a day.[48][47] The highest rainfall total reached more than 39 inches of rainfall in Misato Town.[49] Higher-risk reinsurance arrangements were affected by Nanmadol.[50] At least four people were reported as killed in the country.[51]

South Korea

Although South Korea was not directly hit by the typhoon,[52] the winds and rain caused by Nanmadol also caused inconvenience. Two people were injured, fallen trees were reported, and some locations in the southeast of the country were left without electricity.[3][53] Nanmadol brought heavy rains in the Southeastern Gyeongsang.[54] 7,000 households also experienced a power outages.[3] Over 50 vessels in 43 routes were suspended.[54] President Yoon Suk-yeol instructed his officials to maintain readiness on the storm.[55] In Busan, 155 people and 103 households were evacuated from their homes.[3] Schools in Busan and Ulsan transitioned to distance learning due to safety concerns.[56] Some 101 passenger vessels, and over 79 routes in southern coast were suspended.[56]

See also

- Weather of 2022

- Tropical cyclones in 2022

- 1934 Muroto typhoon – the most intense landfalling typhoon in Japanese history, with a peak low pressure of 911.9 hPa (26.93 inHg)

- Typhoon Vera (1959) – a Category 5-equivalent super typhoon which was the strongest storm to ever impact Japan, with maximum sustained wind speeds of 160 mph (260 km/h) at landfall

- Typhoon Nancy (1961) – another Category 5-equivalent typhoon that hit southwestern Japan and remains among the most intense landfalling Pacific typhoons on record

- Typhoon Olive (1971) – a relatively weaker typhoon which hit southwestern Japan

- Typhoon Oliwa (1997) – an intense typhoon that impacted the same general areas of Japan

- Typhoon Meari (2004) – a strong typhoon which also impacted southwestern Japan

- Typhoon Trami (2018) – another powerful typhoon which also struck western Japan

- Typhoon Kong-rey (2018) – another intense typhoon that had a similar path

- Typhoon Haishen (2020) – an intense typhoon that had a similar path and same intensity

References

- ↑ "Q3 Global Catastrophe Recap" (PDF). Aon Benfield. Retrieved October 21, 2022.

- 1 2 Traylor, Daniel (2022-09-17). "Japan issues rare special warning as 'violent' Typhoon Nanmadol approaches Kyushu". The Japan Times. Archived from the original on 2022-09-16. Retrieved 2022-09-17.

- 1 2 3 4 "Typhoon Nanmadol brushes past nation's southern region". koreatimes. 2022-09-19. Archived from the original on 2022-09-23. Retrieved 2022-09-26.

- 1 2 "Typhoon Nanmadol: Storm damages space centre in Japan, 130,000 still lack power". The Indian Express. 2022-09-20. Retrieved 2023-03-15.

- 1 2 3 Significant Tropical Weather Advisory for the Western and South Pacific Oceans, 13Z 9 September 2022 (Report). United States Joint Typhoon Warning Center. 9 September 2022. Archived from the original on 2017-12-21. Retrieved 9 September 2022. Alt URL

- ↑ "WWJP27 RJTD 090000". Japan Meteorological Agency. 9 September 2022. Archived from the original on 9 September 2022. Retrieved 28 June 2022.

- ↑ Significant Tropical Weather Advisory for the Western and South Pacific Oceans, 06Z 10 September 2022 (Report). United States Joint Typhoon Warning Center. 10 September 2022. Archived from the original on 2017-12-21. Retrieved 10 September 2022. Alt URL

- ↑ Significant Tropical Weather Advisory for the Western and South Pacific Oceans, 06Z 11 September 2022 (Report). United States Joint Typhoon Warning Center. 11 September 2022. Archived from the original on 2017-12-21. Retrieved 11 September 2022. Alt URL

- ↑ Tropical Cyclone Formation Alert (Invest 92W) (Report). United States Joint Typhoon Warning Center. 12 September 2022. Archived from the original on 2022-09-12. Retrieved 12 September 2022. Alt URL

- ↑ Tropical Depression 16W (Sixteen) Warning No. 01 (Report). United States Joint Typhoon Warning Center. 12 September 2022. Retrieved 12 September 2022.

- ↑ Prognostic Reasoning for Tropical Depression 16W (Sixteen) Warning No. 02 (Report). United States Joint Typhoon Warning Center. 13 September 2022. Archived from the original on September 13, 2022. Retrieved 13 September 2022.

- ↑ Prognostic Reasoning for Tropical Storm 16W (Nanmadol) Warning No. 05 (Report). United States Joint Typhoon Warning Center. 13 September 2022. Archived from the original on September 14, 2022. Retrieved 13 September 2022.

- ↑ "RSMC Tropical Cyclone Advisory Name TS 2214 Nanmadol (2214) Upgraded from TD". Japan Meteorological Agency. September 13, 2022. Archived from the original on September 14, 2022. Retrieved September 13, 2022.

- ↑ Prognostic Reasoning for Tropical Storm 16W (Nanmadol) Warning No. 06 (Report). United States Joint Typhoon Warning Center. 14 September 2022. Archived from the original on September 14, 2022. Retrieved 14 September 2022.

- ↑ "RSMC Tropical Cyclone Advisory Name STS 2214 Nanmadol (2214) Upgraded from TS". Japan Meteorological Agency. September 13, 2022. Archived from the original on September 15, 2022. Retrieved September 15, 2022.

- ↑ Prognostic Reasoning for Tropical Storm 16W (Nanmadol) Warning No. 09 (Report). United States Joint Typhoon Warning Center. 14 September 2022. Archived from the original on September 15, 2022. Retrieved 14 September 2022.

- 1 2 Prognostic Reasoning for Typhoon 16W (Nanmadol) Warning No. 11 (Report). United States Joint Typhoon Warning Center. 15 September 2022. Archived from the original on September 15, 2022. Retrieved 15 September 2022.

- ↑ "RSMC Tropical Cyclone Advisory Name TY 2214 Nanmadol (2214) Upgraded from STS". Japan Meteorological Agency. September 15, 2022. Archived from the original on September 15, 2022. Retrieved September 15, 2022.

- ↑ Prognostic Reasoning for Typhoon 16W (Nanmadol) Warning No. 12 (Report). United States Joint Typhoon Warning Center. 15 September 2022. Archived from the original on September 15, 2022. Retrieved 15 September 2022.

- ↑ Prognostic Reasoning for Typhoon 16W (Nanmadol) Warning No. 13 (Report). United States Joint Typhoon Warning Center. 15 September 2022. Archived from the original on September 16, 2022. Retrieved 15 September 2022.

- ↑ Prognostic Reasoning for Typhoon 16W (Nanmadol) Warning No. 14 (Report). United States Joint Typhoon Warning Center. 16 September 2022. Archived from the original on September 16, 2022. Retrieved 16 September 2022.

- ↑ Prognostic Reasoning for Typhoon 16W (Nanmadol) Warning No. 15 (Report). United States Joint Typhoon Warning Center. 16 September 2022. Archived from the original on September 16, 2022. Retrieved 16 September 2022.

- ↑ Prognostic Reasoning for Typhoon 16W (Nanmadol) Warning No. 16 (Report). United States Joint Typhoon Warning Center. 16 September 2022. Archived from the original on September 16, 2022. Retrieved 16 September 2022.

- ↑ "RSMC Tropical Cyclone Advisory Name TY 2214 Nanmadol (2214)". Japan Meteorological Agency. September 16, 2022. Archived from the original on September 17, 2022. Retrieved September 17, 2022.

- ↑ "Tropical Cyclone Bulletin #1F for Super Typhoon 'Josie' (Nanmadol)" (PDF). PAGASA. 16 September 2022. Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 September 2022. Retrieved 16 September 2022. Alt URL

- ↑ Prognostic Reasoning for Typhoon 16W (Nanmadol) Warning No. 17 (Report). United States Joint Typhoon Warning Center. 16 September 2022. Archived from the original on September 17, 2022. Retrieved 16 September 2022.

- ↑ Prognostic Reasoning for Typhoon 16W (Nanmadol) Warning No. 20 (Report). United States Joint Typhoon Warning Center. 17 September 2022. Archived from the original on September 17, 2022. Retrieved 17 September 2022.

- ↑ Prognostic Reasoning for Typhoon 16W (Nanmadol) Warning No. 21 (Report). United States Joint Typhoon Warning Center. 17 September 2022. Archived from the original on September 18, 2022. Retrieved 17 September 2022.

- ↑ Prognostic Reasoning for Typhoon 16W (Nanmadol) Warning No. 22 (Report). United States Joint Typhoon Warning Center. 18 September 2022. Archived from the original on September 18, 2022. Retrieved 18 September 2022.

- ↑ Prognostic Reasoning for Typhoon 16W (Nanmadol) Warning No. 23 (Report). United States Joint Typhoon Warning Center. 18 September 2022. Archived from the original on September 18, 2022. Retrieved 18 September 2022.

- ↑ Prognostic Reasoning for Typhoon 16W (Nanmadol) Warning No. 24 (Report). United States Joint Typhoon Warning Center. 18 September 2022. Archived from the original on September 18, 2022. Retrieved 18 September 2022.

- ↑ Prognostic Reasoning for Typhoon 16W (Nanmadol) Warning No. 25 (Report). United States Joint Typhoon Warning Center. 18 September 2022. Archived from the original on September 19, 2022. Retrieved 18 September 2022.

- ↑ "RSMC Tropical Cyclone Advisory Name STS 2214 Nanmadol (2214) Downgraded from TY". Japan Meteorological Agency. September 16, 2022. Archived from the original on September 19, 2022. Retrieved September 19, 2022.

- ↑ Prognostic Reasoning for Tropical Storm 16W (Nanmadol) Warning No. 26 (Report). United States Joint Typhoon Warning Center. 19 September 2022. Archived from the original on September 19, 2022. Retrieved 19 September 2022.

- ↑ Prognostic Reasoning for Tropical Storm 16W (Nanmadol) Warning No. 27 (Report). United States Joint Typhoon Warning Center. 19 September 2022. Archived from the original on September 19, 2022. Retrieved 19 September 2022.

- ↑ Tropical Storm 16W (Nanmadol) Warning No. 29 (Report). United States Joint Typhoon Warning Center. 19 September 2022. Archived from the original on September 20, 2022. Retrieved 19 September 2022.

- ↑ "RSMC Tropical Cyclone Advisory Name Developed Low Former STS 2214 Nanmadol (2214)". Japan Meteorological Agency. September 20, 2022. Archived from the original on September 20, 2022. Retrieved September 20, 2022.

- ↑ Duff, Renee (September 16, 2022). "Japan braces for flooding, destructive winds from Super Typhoon Nanmadol". Archived from the original on September 16, 2022. Retrieved September 26, 2022.

- ↑ Wulfeck, Andrew (2022-09-16). "Super typhoon takes aim at Japan with life-threatening flooding, damaging winds". FOX Weather. Archived from the original on 2022-09-16. Retrieved 2022-09-17.

- ↑ 日本放送協会. "台風14号【交通】新幹線 運転取りやめ拡大へ 空の欠航700便超 | NHK". NHKニュース. Archived from the original on 2022-09-18. Retrieved 2022-09-18.

- ↑ Yoon, John (2022-09-17). "Japan Warns 'Violent Typhoon' Could Hit on Sunday". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 2022-09-17. Retrieved 2022-09-17.

- ↑ Hauser, Jessie Yeung,Sahar Akbarzai,Jennifer (2022-09-18). "Millions told to evacuate as Typhoon Nanmadol heads for Japan". CNN. Archived from the original on 2022-09-18. Retrieved 2022-09-18.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Hida, Hikari; Yoon, John (2022-09-18). "Powerful Typhoon Thrashes Japan, With Millions Told to Evacuate". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on 2022-09-18. Retrieved 2022-09-18.

- ↑ Bacon, John. "'Raining like never before': Thousands flee as Typhoon Nanmadol slams Japanese coast". USA TODAY. Archived from the original on 2022-09-18. Retrieved 2022-09-18.

- ↑ 日本放送協会. "台風14号【氾濫危険水位超の河川】(19日0:30) | NHK". NHKニュース. Archived from the original on 2022-09-18. Retrieved 2022-09-18.

- ↑ 日本放送協会. "台風14号 九州ほぼ全域が暴風域 中国 四国地方も雨風強まる | NHK". NHKニュース. Archived from the original on 2022-09-18. Retrieved 2022-09-18.

- 1 2 "Four feared dead after typhoon hits Japan". www.dhakatribune.com. 2022-09-20. Archived from the original on 2022-09-20. Retrieved 2022-09-20.

- ↑ 日本放送協会. "台風14号【各地の被害】全国で43人けが 突風による被害も | NHK". NHKニュース. Archived from the original on 2022-09-19. Retrieved 2022-09-19.

- ↑ Zach, Rosenthal (September 19, 2022). "Typhoon Nanmadol slams into Japan, killing at least two". The Washington Post.

- ↑ Artemis.bm, Steven Evans- (2022-09-20). "Typhoon Nanmadol loss likely to attach some reinsurance layers: Twelve - Artemis.bm". Artemis.bm - The Catastrophe Bond, Insurance Linked Securities & Investment, Reinsurance Capital, Alternative Risk Transfer and Weather Risk Management site. Archived from the original on 2022-09-20. Retrieved 2022-09-20.

- ↑ Welle (www.dw.com), Deutsche. "Japan cleans up after Typhoon Nanmadol leaves 4 dead | DW | 20.09.2022". DW.COM. Archived from the original on 2022-09-24. Retrieved 2022-09-26.

- ↑ Woo-hyun, Shim (2022-09-19). "Typhoon Nanmadol hits southern coastal areas of S. Korea". The Korea Herald. Retrieved 2022-09-26.

- ↑ "1 person injured, hundreds evacuated as Typhoon Nanmadol nears". Korea Herald. September 19, 2022. Archived from the original on 19 September 2022. Retrieved 19 September 2022.

- 1 2 "One injured, hundreds evacuated in Korea as Typhoon Nanmadol approaches". koreajoongangdaily.joins.com. 2022-09-19. Archived from the original on 2022-09-25. Retrieved 2022-09-26.

- ↑ 박보람 (2022-09-18). "(LEAD) Yoon calls for thorough readiness for Typhoon Nanmadol". Yonhap News Agency. Archived from the original on 2022-09-19. Retrieved 2022-09-26.

- 1 2 장동우 (2022-09-19). "(2nd LD) 2 people injured, hundreds evacuated as Typhoon Nanmadol brushes past S. Korea". Yonhap News Agency. Retrieved 2022-09-26.

External links

- JTWC Best Track Data of Super Typhoon 16W (Nanmadol)

- 16W.NANMADOL from the U.S. Naval Research Laboratory