Thomas Hutchins | |

|---|---|

| Born | 1730 |

| Died | April 18, 1789 Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, United States |

| Nationality | American |

| Occupation(s) | Cartographer, engineer, geographer, surveyor |

| Known for | Only official Geographer of the United States[1] |

Thomas Hutchins (Monmouth County, NJ 1730 – April 18, 1789, Pittsburgh) was an American military engineer, cartographer, geographer and surveyor. In 1781, Hutchins was named Geographer of the United States. He is the only person to hold that post.[1]

Biography

Hutchins was born in New Jersey.[1]"When only sixteen years of age he went to the western country, and obtained an appointment as an ensign in the British Army."[2] "He joined the militia during the French and Indian War[1] and later took a regular commission with British forces. "...he fought in the French and Indian War (1754–1763). By late 1757, was commissioned a lieutenant in the colony of Pennsylvania, and a year later he was promoted to quartermaster in Colonel Hugh Mercer’s battalion and was stationed at Fort Duquesne near Pittsburgh."[3]

"In 1763 General Henry Bouquet, a British officer then in command at Philadelphia, was ordered to the relief of Fort Pitt, now Pittsburgh, and setting out with 500 men, mostly Highlanders, found the frontier settlements greatly alarmed on account of savage invasions. He has some fighting with the Indians along the way, but succeeded in reaching Fort Pitt with supplies, losing, however, eight officers and one hundred and fifteen men. Hutchins was present at this point, and distinguished himself as a soldier, while he laid out the plan of new fortifications, and afterwards executed it under the directions of General Bouquet."[2]

In 1766, he started working for the British army as an engineer.[1] That year, Hutchins joined George Croghan, deputy Indian agent, and Captain Henry Gordon, chief engineer in the Western Department of North America, on an expedition down the Ohio River to survey territory acquired by the 1763 Treaty of Paris. Hutchins worked in the Midwestern territories on land and river surveys for several years until he was transferred to the Southern Department of North America in 1772. He spent about five years working on survey projects in the western part of Florida. During this time he also occasionally traveled north, often to Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. His advancements in the fields of topography and geography led him to be elected a member of the American Philosophical Society in the spring of 1772.[4] In 1771 he submitted an account of the Illinois country by letter.[5] In 1773 he gave information on the Chester and Middle rivers of Florida.[6]

In 1774, he participated in a survey of the Mississippi river from Manchac to the Yazoo River. This was a mapping expedition led by George Gauld, with Dr. John Lorimer and Captain Thomas Davey, Captain of HMS Sloop Diligence. Also along on part of the expedition was Major Alexander Dickson, commander of the 16th Regiment in West Florida. Much of the data used by Hutchins in preparing his 1784 book, "Historical, Narrative and Topographical Description of Louisiana and West Florida" came from his experiences on this expedition.

Despite his years of service with the British Army, he sympathized with the American cause during the American Revolution. One Journal of these events, written in his handwriting in three different versions, was likely meant for the planned biography that was never finished. It indicates that Hutchins accompanied his old 60th Royal American Regiment for a brief time during the invasion of Georgia in December 1778. Similar to other anonymous journals attributed to Hutchins, he describes the countryside while serving beside a fellow New Jersey acquaintance Lieut. Col. Mark Prevost, brother of the Gen. Augustine Prevost. Captain Hutchins apparently accompanied his regiment just days before the Battle of Brier Creek which was fought on March 3, 1779 in Georgia. He may have served in one of his previous capacities with the Prevost's during the French and Indians War as a recorder and observer of the battle. Hutchins, although not directly in the fighting himself, witnessed and recorded cruelties that may have cemented his anti-war stance toward hostilities against the Americans. Hutchins' veteran observations recorded some of the most vivid descriptions of the battle as the light infantry regiment, led by the infamous Capt. James "Bloody" Baird of the 71st Fraser Highlanders, started bayoneting Georgia Continentals after their surrender. Hutchins descriptions of the 71st Highlanders seem to give hint of what may have been commonly held prejudices held by British Regular officers serving alongside Scottish Regiments. Some days after the event, Hutchins likely sailed for Great Britain from Savannah, Georgia to print cartography materials of frontier America. Sometime during the preceding weeks, a secret investigation of the activities of Hutchins was apparently set in motion. An agent had discovered that Hutchins had been using a secret mailing address and sending coded dispatches. Some mention of Hutchins' activities and letters were made by Thomas Digges in letters exchanged with Benjamin Franklin. It is not clear if this was espionage or his continued attention to land speculation activities he was involved in back in America. Since Capt. Hutchins was considered one of Britain's leading authorities on the western frontier lands, this left him in the unusual position of being an important consultant about lucrative future Native American land acquisitions. Some American and British leaders were involved in these activities so when news of his investigation surfaced, many recognized this as a potentially scandalous affair. Some such individuals were the Prevost family members who all but represented the heart of the command for the 60th Regiment. One such connection was in the messy affair of the George Croghan lands of Western Pennsylvania. The potential may have been viewed as serious enough to have the American 60th Regiment moved from the states to Jamaica by the end of 1779. Likely suspecting his investigation, Hutchins tried to sell his captaincy in the Regiment. Hutchins resigned from his position in 1780.[1][7] He was arrested, charged with treason, and imprisoned in a mostly secretive set of events. In 1780, he escaped to France and contacted Benjamin Franklin in the United States with a request to join the American army. In December 1780, Hutchins sailed to Charleston, South Carolina. Very little is known of his service with the Americans during the remainder of the war. Hutchins is believed to be the only British Regular Officer to have switched to the American side during the war.

"By resolution on May 4, 1781, Congress appointed him geographer of the southern army. On July 11, the title was changed to 'Geographer of the United States.'"[8] Hutchins was the first and only Geographer of the United States [9] (see Department of the Geographer to the Army, 1777-1783). He became an early advocate of Manifest Destiny, proposing that the United States should annex West Florida and Louisiana, which were then controlled by Spain.[7]

In May 1781, Hutchins was appointed geographer of the southern army, and shared duties with Simeon DeWitt, the geographer of the main army. Just a few months later, a new title was granted to both men, geographer of the United States. When DeWitt became the surveyor-general of New York in 1784, Hutchins held the prestigious title alone.

"Although Congress balked at the idea of a postwar establishment with an engineering department, it did see the need for a geographer and surveyors. Thus, in 1785, Thomas Hutchins became geographer general and immediately began his biggest assignment- surveying "Seven Ranges" townships in the Northwest Territory as provided by the Land Ordnance Act of 1785. For two years Josiah Harmar's troops offered Hutchins and his surveyors much needed protection from Indians."[10]

Hutchins died on assignment while surveying the Seven Ranges.[11] "The Gazette of the United States concluded a commendary memorial notice by the remark, 'he has measured the earth, but a small space now contains him.'"[12] He was interred at the cemetery of the First Presbyterian Church of Pittsburgh.

References

Citations

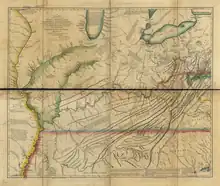

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "A New Map of the Western Parts of Virginia, Pennsylvania, Maryland, and North Carolina, 1778". World Digital Library. 1778. Retrieved 2013-06-08.

- 1 2 The National Cyclopaedia of American Biography. NY: White & Co. 1899. Volume IX, page 267.

- ↑ "Thomas Hutchins Papers. Historical Society of Pennsylvania.

- ↑ "APS Member History".

- ↑ “Volume 1769-1774.” Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society, vol. 22, no. 119, 1885, p. 69. JSTOR website Retrieved 24 Dec. 2022.

- ↑ Proceedings, p. 80

- 1 2 Longly York, Neil (2003). Turning the World Upside Down: the War of American Independence and the Problem of Empire. [www.praeger.com Praeger Publishers]. p. 159. ISBN 0-275-97693-9.

- ↑ "Thomas Hutchins." Dictionary of American Biography. NY: Scribner's Sons. 1932. Volume IX, page 435.

- ↑ Fort Steuben History

- ↑ Walker, Paul K. Engineers of Independence: A Documentary History of the Army Engineers in the American Revolution, 1775–1783. [Washington, D.C.]: Historical Division, Office of Administrative Services, Office of the Chief of Engineers, 1981. Page 365.

- ↑ , University of Pittsburgh

- ↑ "Thomas Hutchins." Dictionary of American Biography. NY: Scribner's Sons. 1932. Volume IX, page 436.

Sources

- The Lewis and Clark Journal of Discovery

- "Thomas Hutchins", Ohio History Central: An Online Encyclopedia of Ohio History, Ohio Historical Society, 2005.

- Hicks, Fredrick (1904). "Biographical Sketch of Thomas Hutchins". In Hicks, Fredrick (ed.). A Topographical Description of Virginia, Pennsylvania, Maryland and North Carolina, reprinted from the original edition of 1778. Cleveland: The Burrow Brothers Company. pp. 7–51. Retrieved 1 December 2010.

- . Appletons' Cyclopædia of American Biography. 1900.

- "Thomas Hutchins." The National Cyclopaedia of American Biography. NY: White & Co. 1899. Volume IX, page 267.

- "Thomas Hutchins." Dictionary of American Biography. NY: Scribner's Sons. 1932. Volume IX, pages 435–436.

Bibliography

- Hutchins, Thomas. "Experiments on the Dipping Needle, Made by Desire of the Royal Society." Read before the Society, on February 16, 1775. Royal Society. Philosophical Transactions Volume 65 (1775), pages 129-138.

- Hutchins, Thomas. Historical, Narrative and Topographical Description of Louisiana and West Florida, containing the River Mississippi with its Principal Branches and Settlements, and the Rivers Pearl, Pascagoula, Mobile, Perdido, Escambia, Chacta-Hatcha, &c. Philadelphia: Robert Aiken. 1784.

- Hutchins, Thomas. A Topographical Description of Virginia, Pennsylvania, Maryland, and North Carolina, 1778. Reprint with biographical sketch and list of Hutchins’s works by Frederick Charles Hicks. Cleveland: The Burrows Brothers, 1904.

- Smith, William. "Account of Bouquet's Expedition. Philadelphia. 1765. Hutchins supplied the maps and plates for this publication.

External links

- The Thomas Hutchins Papers, spanning the bulk of Hutchins's career from the 1750s to the 1780s, are available for research use at the Historical Society of Pennsylvania.