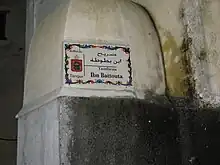

Historic copy of selected parts of the Travel Report by Ibn Battuta, 1836 CE, Cairo | |

| Author | Ibn Battuta |

|---|---|

| Original title | تحفة النظار في غرائب الأمصار وعجائب الأسفار Tuḥfat an-Nuẓẓār fī Gharāʾib al-Amṣār wa ʿAjāʾib al-Asfār |

| Country | Morocco |

| Language | Arabic |

| Subject | Geography |

| Genre | Travelogue |

| Website | Arabic text at wdl.org, English translation at archive.org |

The Rihla, formal title A Masterpiece to Those Who Contemplate the Wonders of Cities and the Marvels of Traveling, is the travelogue written by Ibn Battuta, documenting his lifetime of travel and exploration, which according to his description covered about 73,000 miles (117,000 km). Rihla is the Arabic word for a journey or the travelogue that documents it.

Battuta's travels

Ibn Battuta may have travelled significantly farther than any other person in history up to his time; certainly his account describes more travel than any other pre-jet age explorer on record.

Ibn Battuta's first voyage began in 1,325 CE, in Morocco, when the 21 year old set out on his Hajj, the religious pilgrimage to Mecca expected of all followers of Islam. During this time period, it would normally take pilgrims a year to a year and a half to complete the Hajj. However, Ibn Battuta found he loved travel during the experience, and reportedly encountered a Sufi mystic who told him that he would eventually visit the entire Islamic world. Ibn Battuta spent the next two decades exploring much of the known world. Twenty-four years after departing Morocco, he finally finally returned home to write about his travels.

The Hajj

He travelled to Mecca overland, following the North African coast across the sultanates of Abd al-Wadid and Hafsid. He took a bride in the town of Sfax,[1] the first in a series of marriages that would feature in his travels.[2]

In the early spring of 1326, after a journey of over 3,500 km (2,200 mi), Ibn Battuta arrived at the port of Alexandria, at the time part of the Bahri Mamluk empire. He met two ascetic pious men in Alexandria. One was Sheikh Burhanuddin who is supposed to have foretold the destiny of Ibn Battuta as a world traveller saying "It seems to me that you are fond of foreign travel. You will visit my brother Fariduddin in India, Rukonuddin in Sind and Burhanuddin in China. Convey my greetings to them". Another pious man Sheikh Murshidi interpreted the meaning of a dream of Ibn Battuta that he was meant to be a world traveller.[3][4]

At this point he began a lifelong habit of making side-trips instead of getting where he was going. He spent several weeks visiting sites in the area and then headed inland to Cairo, the capital of the Mamluk Sultanate and an important city. Of the three usual routes to Mecca, Ibn Battuta chose the least-travelled, which involved a journey up the Nile valley, then east to the Red Sea port of Aydhab.[lower-alpha 1] Upon approaching the town, however, a local rebellion forced him to turn back.[6]

He returned to Cairo and took a second side trip, this time to Mamluk-controlled Damascus. He described travelling on a complicated zig-zag route across Palestine in which he visited more than twenty cities.

After spending the Muslim month of Ramadan in Damascus, he joined a caravan travelling the 1,300 km (810 mi) south to Medina, site of the Mosque of the Islamic prophet Muhammad. After four days in the town, he journeyed on to Mecca, where upon completing his pilgrimage he took the honorific status of El-Hajji. Rather than returning home, Ibn Battuta decided to continue traveling, choosing as his next destination the Ilkhanate, a Mongol Khanate, to the northeast.[7]

Ibn Battuta then started back toward Iraq,[8] but got diverted on a six-month detour that took him into Persia. Finally, he returned across to Baghdad, arriving there in 1327.[9]

In Baghdad, he found Abu Sa'id, the last Mongol ruler of the unified Ilkhanate, leaving the city and heading north with a large retinue.[10] Ibn Battuta joined the royal caravan for a while, then turned north on the Silk Road to Tabriz.

Second pilgrimage to Mecca

Ibn Battuta left again for Baghdad, probably in July, but first took an excursion northwards along the river Tigris. He visited Mosul, where he was the guest of the Ilkhanate governor,[11] and then the towns of Cizre (Jazirat ibn 'Umar) and Mardin in modern-day Turkey. At a hermitage on a mountain near Sinjar, he met a Kurdish mystic who gave him some silver coins.[lower-alpha 2][14] Once back in Mosul, he joined a "feeder" caravan of pilgrims heading south to Baghdad, where they would meet up with the main caravan that crossed the Arabian Desert to Mecca. Ill with diarrhoea, he arrived in the city weak and exhausted for his second hajj.[15]

From Aden Ibn Battuta embarked on a ship heading for Zeila on the coast of Somalia. Later he would visit Mogadishu, the then pre-eminent city of the "Land of the Berbers" (بلد البربر Bilad al-Barbar, the medieval Arabic term for the Horn of Africa).[16][17][18]

Ibn Battuta arrived in Mogadishu in 1331, at the zenith of its prosperity. He described Mogadishu as "an exceedingly large city" with many rich merchants, which was famous for its high quality fabric that it exported to Egypt, among other places.[19][20] He also describes the hospitality of the people of Mogadishu and how locals would put travelers up in their home to help the local economy.[21] Battuta added that the city was ruled by a Somali sultan, Abu Bakr ibn Shaikh 'Umar,[22][23] who had a Barbara origin, an ancient term to describe the ancestors of the Somali people. He spoke the Mogadishan Somali or Banadiri Somali (referred to by Battuta as Benadir) language as well as Arabic with equal fluency.[23][24] The sultan also had a retinue of wazirs (ministers), legal experts, commanders, royal eunuchs, and other officials at his beck and call.[23]

Ibn Battuta continued by ship south to the Swahili Coast, a region then known in Arabic as the Bilad al-Zanj ("Land of the Zanj"),[25] with an overnight stop at the island town of Mombasa.[26] Although relatively small at the time, Mombasa would become important in the following century.[27] After a journey along the coast, Ibn Battuta next arrived in the island town of Kilwa in present-day Tanzania,[28] which had become an important transit centre of the gold trade.[29] He described the city as "one of the finest and most beautifully built towns; all the buildings are of wood, and the houses are roofed with dīs reeds".[30]

Byzantium

After his third pilgrimage to Mecca, Ibn Battuta decided to seek employment with the Muslim Sultan of Delhi, Muhammad bin Tughluq. In the autumn of 1330 (or 1332), he set off for the Seljuk controlled territory of Anatolia with the intention of taking an overland route to India.[31]

From this point the itinerary across Anatolia in the Rihla is confused. Ibn Battuta describes travelling westwards from Eğirdir to Milas and then skipping 420 km (260 mi) eastward past Eğirdir to Konya. He then continues travelling in an easterly direction, reaching Erzurum from where he skips 1,160 km (720 mi) back to Birgi which lies north of Milas.[32] Historians believe that Ibn Battuta visited a number of towns in central Anatolia, but not in the order that he describes.[33][lower-alpha 3]

When they reached Astrakhan, Öz Beg Khan had just given permission for one of his pregnant wives, Princess Bayalun, a daughter of Byzantine emperor Andronikos III Palaiologos, to return to her home city of Constantinople to give birth. Ibn Battuta talked his way into this expedition, which would be his first beyond the boundaries of the Islamic world.[36]

Arriving in Constantinople towards the end of 1332 (or 1334), he met the Byzantine emperor Andronikos III Palaiologos. He visited the great church of Hagia Sophia and spoke with an Eastern Orthodox priest about his travels in the city of Jerusalem. After a month in the city, Ibn Battuta returned to Astrakhan, then arrived in the capital city Sarai al-Jadid and reported the accounts of his travels to Sultan Öz Beg Khan (r. 1313–1341). Then he continued past the Caspian and Aral Seas to Bukhara and Samarkand, where he visited the court of another Mongolian king, Tarmashirin (r. 1331–1334) of the Chagatai Khanate.[37] From there he journeyed south to Afghanistan, then crossed into India via the mountain passes of the Hindu Kush.[38] In the Rihla, he mentions these mountains and the history of the range in slave trading.[39][40] He wrote,

After this I proceeded to the city of Barwan, in the road to which is a high mountain, covered with snow and exceedingly cold; they call it the Hindu Kush, that is Hindu-slayer, because most of the slaves brought thither from India die on account of the intenseness of the cold.

India

Ibn Battuta and his party reached the Indus River on 12 September 1333.[42] From there, he made his way to Delhi and became acquainted with the sultan, Muhammad bin Tughluq.

On the strength of his years of study in Mecca, Ibn Battuta was appointed a qadi, or judge, by the sultan.[43] However, he found it difficult to enforce Islamic law beyond the sultan's court in Delhi, due to lack of Islamic appeal in India.[44]

The Sultan was erratic even by the standards of the time and for six years Ibn Battuta veered between living the high life of a trusted subordinate and falling under suspicion of treason for a variety of offences. His plan to leave on the pretext of taking another hajj was stymied by the Sultan. The opportunity for Battuta to leave Delhi finally arose in 1341 when an embassy arrived from Yuan dynasty China asking for permission to rebuild a Himalayan Buddhist temple popular with Chinese pilgrims.[lower-alpha 4][48]

China

Ibn Battuta was given charge of the embassy but en route to the coast at the start of the journey to China, he and his large retinue were attacked by a group of bandits.[49] Separated from his companions, he was robbed and nearly lost his life.[50] Despite this setback, within ten days he had caught up with his group and continued on to Khambhat in the Indian state of Gujarat. From there, they sailed to Calicut (now known as Kozhikode), where Portuguese explorer Vasco da Gama would land two centuries later. While in Calicut, Battuta was the guest of the ruling Zamorin.[43] While Ibn Battuta visited a mosque on shore, a storm arose and one of the ships of his expedition sank.[51] The other ship then sailed without him only to be seized by a local Sumatran king a few months later.

In 1345 Ibn Battuta travelled on to Samudra Pasai Sultanate in present-day Aceh, Northern Sumatra, where he notes in his travel log that the ruler of Samudra Pasai was a pious Muslim named Sultan Al-Malik Al-Zahir Jamal-ad-Din, who performed his religious duties with utmost zeal and often waged campaigns against animists in the region. The island of Sumatra, according to Ibn Battuta, was rich in camphor, areca nut, cloves, and tin.[52]

The madh'hab he observed was Imam Al-Shafi‘i, whose customs were similar to those he had previously seen in coastal India, especially among the Mappila Muslims, who were also followers of Imam Al-Shafi‘i. At that time Samudra Pasai marked the end of Dar al-Islam, because no territory east of this was ruled by a Muslim. Here he stayed for about two weeks in the wooden walled town as a guest of the sultan, and then the sultan provided him with supplies and sent him on his way on one of his own junks to China.[52]

Ibn Battuta first sailed to Malacca on the Malay Peninsula which he called "Mul Jawi". He met the ruler of Malacca and stayed as a guest for three days.

In the year 1345 Ibn Battuta arrived at Quanzhou in China's Fujian province, then under the rule of the Mongols. One of the first things he noted was that Muslims referred to the city as "Zaitun" (meaning olive), but Ibn Battuta could not find any olives anywhere. He mentioned local artists and their mastery in making portraits of newly arrived foreigners; these were for security purposes. Ibn Battuta praised the craftsmen and their silk and porcelain; as well as fruits such as plums and watermelons and the advantages of paper money.[53]

He then travelled south along the Chinese coast to Guangzhou, where he lodged for two weeks with one of the city's wealthy merchants.[54]

Ibn Battuta travelled from Beijing to Hangzhou and then proceeded to Fuzhou. Upon his return to Quanzhou, he soon boarded a Chinese junk owned by the Sultan of Samudera Pasai Sultanate heading for Southeast Asia, whereupon Ibn Battuta was unfairly charged a hefty sum by the crew and lost much of what he had collected during his stay in China.[55]

Al-Andalus / Spain

After a few days in Tangier, Ibn Battuta set out for a trip to the Muslim-controlled territory of al-Andalus on the Iberian Peninsula. King Alfonso XI of Castile and León had threatened to attack Gibraltar; so in 1350, Ibn Battuta joined a group of Muslims leaving Tangier with the intention of defending the port.[56] By the time he arrived, the Black Death had killed Alfonso and the threat of invasion had receded, so he turned the trip into a sight-seeing tour, travelling through Valencia and ending up in Granada.[57]

After his departure from al-Andalus he decided to travel through Morocco. On his return home, he stopped for a while in Marrakech, which was almost a ghost town following the recent plague and the transfer of the capital to Fez.[58]

In the autumn of 1351, Ibn Battuta left Fez and made his way to the town of Sijilmasa on the northern edge of the Sahara in present-day Morocco.[59] There he bought a number of camels and stayed for four months. He set out again with a caravan in February 1352 and after 25 days arrived at the dry salt lake bed of Taghaza with its salt mines. All of the local buildings were made from slabs of salt by the slaves of the Masufa tribe, who cut the salt in thick slabs for transport by camel. Taghaza was a commercial centre and awash with Malian gold, though Ibn Battuta did not form a favourable impression of the place, recording that it was plagued by flies and the water was brackish.[60]

Mali Empire

After a ten-day stay in Taghaza, the caravan set out for the oasis of Tasarahla (probably Bir al-Ksaib)[61][lower-alpha 5] where it stopped for three days in preparation for the last and most difficult leg of the journey across the vast desert. From Tasarahla, a Masufa scout was sent ahead to the oasis town of Oualata, where he arranged for water to be transported a distance of four days travel where it would meet the thirsty caravan. Oualata was the southern terminus of the trans-Saharan trade route and had recently become part of the Mali Empire. Altogether, the caravan took two months to cross the 1,600 km (990 mi) of desert from Sijilmasa.[62]

From there Ibn Battuta travelled southwest along a river he believed to be the Nile (it was actually the river Niger), until he reached the capital of the Mali Empire.[lower-alpha 6] There he met Mansa Suleyman, king since 1341. Ibn Battuta disapproved of the fact that female slaves, servants and even the daughters of the sultan went about exposing parts of their bodies not befitting a Muslim.[64] He left the capital in February accompanied by a local Malian merchant and journeyed overland by camel to Timbuktu.[65] Though in the next two centuries it would become the most important city in the region, at that time it was a small city and relatively unimportant.[66] It was during this journey that Ibn Battuta first encountered a hippopotamus. The animals were feared by the local boatmen and hunted with lances to which strong cords were attached.[67] After a short stay in Timbuktu, Ibn Battuta journeyed down the Niger to Gao in a canoe carved from a single tree. At the time Gao was an important commercial center.[68]

After spending a month in Gao, Ibn Battuta set off with a large caravan for the oasis of Takedda. On his journey across the desert, he received a message from the Sultan of Morocco commanding him to return home. He set off for Sijilmasa in September 1353, accompanying a large caravan transporting 600 female slaves, and arrived back in Morocco early in 1354.[69]

Ibn Battuta's itinerary gives scholars a glimpse as to when Islam first began to spread into the heart of west Africa.[70]

The travelogue

After returning home from his travels in 1354, and at the suggestion of the Marinid ruler of Morocco, Abu Inan Faris, Ibn Battuta dictated an account in Arabic of his journeys to Ibn Juzayy, a scholar whom he had previously met in Granada. The account is the only source for Ibn Battuta's adventures. The full title of the manuscript may be translated as A Masterpiece to Those Who Contemplate the Wonders of Cities and the Marvels of Travelling (تحفة النظار في غرائب الأمصار وعجائب الأسفار, Tuḥfat an-Nuẓẓār fī Gharāʾib al-Amṣār wa ʿAjāʾib al-Asfār).[71][lower-alpha 7] However, it is often simply referred to as The Travels (الرحلة, Rihla),[73] in reference to a standard form of Arabic literature.

There is no indication that Ibn Battuta made any notes or had any journal during his twenty-nine years of travelling.[lower-alpha 8] When he came to dictate an account of his experiences he had to rely on memory and manuscripts produced by earlier travellers. Ibn Juzayy did not acknowledge his sources and presented some of the earlier descriptions as Ibn Battuta's own observations. When describing Damascus, Mecca, Medina and some other places in the Middle East, he clearly copied passages from the account by the Andalusian Ibn Jubayr which had been written more than 150 years earlier.[75] Similarly, most of Ibn Juzayy's descriptions of places in Palestine were copied from an account by the 13th-century traveller Muhammad al-Abdari.[76]

Many scholars of the Oriental studies do not believe that Ibn Battuta visited all the places he described, arguing that in order to provide a comprehensive description of places in the Muslim world, he relied at least in part on hearsay evidence, making use of accounts by earlier travellers. For example, it is considered very unlikely that Ibn Battuta made a trip up the Volga River from New Sarai to visit Bolghar,[77] and there are serious doubts about a number of other journeys such as his trip to Sana'a in Yemen,[78] his journey from Balkh to Bistam in Khorasan[79] and his trip around Anatolia.[80]

Ibn Battuta's claim that a Maghrebian called "Abu'l Barakat the Berber" converted the Maldives to Islam is contradicted by an entirely different story which says that the Maldives were converted to Islam after miracles were performed by a Tabrizi named Maulana Shaikh Yusuf Shams-ud-din according to the Tarikh, the official history of the Maldives.[81]

Some scholars have also questioned whether he really visited China.[82] Ibn Battuta may have plagiarized entire sections of his descriptions of China lifted from works by other authors like "Masalik al-absar fi mamalik al-amsar" by Shihab al-Umari, Sulaiman al-Tajir, and possibly from Al Juwayni, Rashid-al-Din Hamadani and an Alexander romance. Furthermore, Ibn Battuta's description and Marco Polo's writings share extremely similar sections and themes, with some of the same commentary, e.g. it is unlikely that the 3rd Caliph Uthman ibn Affan had someone with the exact identical name in China who was encountered by Ibn Battuta.[83]

However, even if the Rihla is not fully based on what its author personally witnessed, it provides an important account of much of the 14th-century world. Concubines were used by Ibn Battuta such as in Delhi.[74]: 111–13, 137, 141, 238 [84] He wedded several women, divorced at least some of them, and in Damascus, Malabar, Delhi, Bukhara, and the Maldives had children by them or by concubines.[85] Ibn Battuta insulted Greeks as "enemies of Allah", drunkards and "swine eaters", while at the same time in Ephesus he purchased and used a Greek girl who was one of his many slave girls in his "harem" through Byzantium, Khorasan, Africa, and Palestine.[86] It was two decades before he again returned to find out what happened to one of his wives and child in Damascus.[87]

Ibn Battuta often experienced culture shock in regions he visited where the local customs of recently converted peoples did not fit in with his orthodox Muslim background. Among the Turks and Mongols, he was astonished at the freedom and respect enjoyed by women and remarked that on seeing a Turkish couple in a bazaar one might assume that the man was the woman's servant when he was in fact her husband.[88] He also felt that dress customs in the Maldives and some sub-Saharan regions in Africa, were too revealing.

Little is known about Ibn Battuta's life after completion of his Rihla in 1355. He was appointed a judge in Morocco and died in 1368 or 1369.[89]

Ibn Battuta's work was unknown outside the Muslim world until the beginning of the 19th century, when the German traveller-explorer Ulrich Jasper Seetzen (1767–1811) acquired a collection of manuscripts in the Middle East, among which was a 94-page volume containing an abridged version of Ibn Juzayy's text. Three extracts were published in 1818 by the German orientalist Johann Kosegarten.[90] A fourth extract was published the following year.[91] French scholars were alerted to the initial publication by a lengthy review published in the Journal de Savants by the orientalist Silvestre de Sacy.[92]

Three copies of another abridged manuscript were acquired by the Swiss traveller Johann Burckhardt and bequeathed to the University of Cambridge. He gave a brief overview of their content in a book published posthumously in 1819.[93] The Arabic text was translated into English by the orientalist Samuel Lee and published in London in 1829.[94]

In the 1830s, during the French occupation of Algeria, the Bibliothèque Nationale (BNF) in Paris acquired five manuscripts of Ibn Battuta's travels, in which two were complete.[lower-alpha 9] One manuscript containing just the second part of the work is dated 1356 and is believed to be Ibn Juzayy's autograph.[99] The BNF manuscripts were used in 1843 by the Irish-French orientalist Baron de Slane to produce a translation into French of Ibn Battuta's visit to Sudan.[100] They were also studied by the French scholars Charles Defrémery and Beniamino Sanguinetti. Beginning in 1853 they published a series of four volumes containing a critical edition of the Arabic text together with a translation into French.[101] In their introduction Defrémery and Sanguinetti praised Lee's annotations but were critical of his translation which they claimed lacked precision, even in straightforward passages.[lower-alpha 10]

In 1929, exactly a century after the publication of Lee's translation, the historian and orientalist Hamilton Gibb published an English translation of selected portions of Defrémery and Sanguinetti's Arabic text.[103] Gibb had proposed to the Hakluyt Society in 1922 that he should prepare an annotated translation of the entire Rihla into English.[104] His intention was to divide the translated text into four volumes, each volume corresponding to one of the volumes published by Defrémery and Sanguinetti. The first volume was not published until 1958.[105] Gibb died in 1971, having completed the first three volumes. The fourth volume was prepared by Charles Beckingham and published in 1994.[106] Defrémery and Sanguinetti's printed text has now been translated into number of other languages.

Notes

- ↑ Aydhad was a port on the west coast of the Red Sea at 22°19′51″N 36°29′25″E / 22.33083°N 36.49028°E.[5]

- ↑ Most of Ibn Battuta's descriptions of the towns along the Tigris are copied from Ibn Jabayr's Rihla from 1184.[12][13]

- ↑ This is one of several occasions where Ibn Battuta interrupts a journey to branch out on a side trip only to later skip back and resume the original journey. Gibb describes these side trips as "divagations".[34] The divagation through Anatolia is considered credible as Ibn Battuta describes numerous personal experiences and there is sufficient time between leaving Mecca in mid-November 1330 and reaching Eğirdir on the way back from Erzurum at the start of Ramadan (8 June) in 1331.[33] Gibb still admits that he found it difficult to believe that Ibn Battuta actually travelled as far east as Erzurum.[35]

- ↑ In the Rihla the date of Ibn Battuta's departure from Delhi is given as 17 Safar 743 AH or 22 July 1342.[45][46] Dunn has argued that this is probably an error and to accommodate Ibn Battuta's subsequent travels and visits to the Maldives it is more likely that he left Delhi in 1341.[47]

- ↑ Bir al-Ksaib (also Bir Ounane or El Gçaib) is in northern Mali at 21°17′33″N 5°37′30″W / 21.29250°N 5.62500°W. The oasis is 265 km (165 mi) south of Taghaza and 470 km (290 mi) north of Oualata.

- ↑ The location of the Malian capital has been the subject of considerable scholarly debate but there is no consensus. The historian, John Hunwick has studied the times given by Ibn Battuta for the various stages of his journey and proposed that the capital is likely to have been on the left side of the Niger River somewhere between Bamako and Nyamina.[63]

- ↑ Dunn gives the clunkier translation A Gift to the Observers Concerning the Curiosities of the Cities and the Marvels Encountered in Travels.[72]

- ↑ Though he mentions being robbed of some notes[74]

- ↑ Neither de Slane's 19th century catalogue[95] nor the modern online equivalent provide any information on the provenance of the manuscripts.[96] Dunn states that all five manuscripts were "found in Algeria"[97] but in their introduction Defrémery and Sanguinetti mention that the BNF had acquired one manuscript (MS Supplément arabe 909/Arabe 2287) from M. Delaporte, a former French consul to Morocco.[98]

- ↑ French: "La version de M. Lee manque quelquefois d'exactitude, même dans des passage fort simples et très-faciles".[102]

References

- ↑ "Ibn Battuta: Travels in Asia and Africa 1325–1354". Deborah Mauskopf Deliyannis. Indiana University Bloomington. Archived from the original on 20 August 2017. Retrieved 6 December 2017.

- ↑ Dunn 2005, p. 39; Defrémery & Sanguinetti 1853, p. 26 Vol. 1

- ↑ The Travels of Ibn Battuta, A.D. 1325-1354: Volume I, translated by H.A.R Gibb, pp. 23-24

- ↑ Defrémery & Sanguinetti 1853, p. 27 Vol. 1

- ↑ Peacock & Peacock 2008.

- ↑ Dunn 2005, pp. 53–54

- ↑ Dunn 2005, pp. 66–79.

- ↑ Dunn 2005, pp. 88–89; Defrémery & Sanguinetti 1853, p. 404 Vol. 1; Gibb 1958, p. 249 Vol. 1

- ↑ Dunn 2005, p. 97; Defrémery & Sanguinetti 1854, p. 100 Vol. 2

- ↑ Dunn 2005, pp. 98–100; Defrémery & Sanguinetti 1854, p. 125 Vol. 2

- ↑ Defrémery & Sanguinetti 1854, pp. 134–39 Vol. 2.

- ↑ Mattock 1981.

- ↑ Dunn 2005, p. 102.

- ↑ Dunn 2005, p. 102; Defrémery & Sanguinetti 1854, p. 142 Vol. 2

- ↑ Dunn 2005, pp. 102–03; Defrémery & Sanguinetti 1854, p. 149 Vol. 2

- ↑ Sanjay Subrahmanyam, The Career and Legend of Vasco Da Gama, (Cambridge University Press: 1998), pp. 120–21.

- ↑ J.D. Fage, Roland Oliver, Roland Anthony Oliver, The Cambridge History of Africa, (Cambridge University Press: 1977), p. 190.

- ↑ George Wynn Brereton Huntingford, Agatharchides, The Periplus of the Erythraean Sea: With Some Extracts from Agatharkhidēs "On the Erythraean Sea", (Hakluyt Society: 1980), p. 83.

- ↑ P. L. Shinnie, The African Iron Age, (Clarendon Press: 1971), p.135

- ↑ Helen Chapin Metz, ed. (1992). Somalia: A Country Study. US: Federal Research Division, Library of Congress. ISBN 978-0844407753.

- ↑ Battutah, Ibn (2002). The Travels of Ibn Battutah. London: Picador. pp. 88–89. ISBN 9780330418799.

- ↑ Versteegh, Kees (2008). Encyclopedia of Arabic language and linguistics, Volume 4. Brill. p. 276. ISBN 978-9004144767.

- 1 2 3 David D. Laitin, Said S. Samatar, Somalia: Nation in Search of a State, (Westview Press: 1987), p. 15.

- ↑ Chapurukha Makokha Kusimba, The Rise and Fall of Swahili States, (AltaMira Press: 1999), p.58

- ↑ Chittick 1977, p. 191

- ↑ Gibb 1962, p. 379 Vol. 2

- ↑ Dunn 2005, p. 126

- ↑ Defrémery & Sanguinetti 1854, p. 192 Vol. 2

- ↑ Dunn 2005, pp. 126–27

- ↑ Gibb 1962, p. 380 Vol. 2; Defrémery & Sanguinetti 1854, p. 193, Vol. 2

- ↑ Dunn 2005, pp. 137–39.

- ↑ Gibb 1962, pp. 424–28 Vol. 2.

- 1 2 Dunn 2005, pp. 149–50, 157 Note 13; Gibb 1962, pp. 533–35, Vol. 2; Hrbek 1962, pp. 455–62.

- ↑ Gibb 1962, pp. 533–35, Vol. 2.

- ↑ Gibb 1962, p. 535, Vol. 2.

- ↑ Dunn 2005, pp. 169–71

- ↑ "The_Longest_Hajj_Part2_6". hajjguide.org. Archived from the original on 24 September 2014. Retrieved 13 June 2015.

- ↑ "Khan Academy". Khan Academy. Archived from the original on 6 December 2017. Retrieved 6 December 2017.

- ↑ Dunn 2005, pp. 171–78

- 1 2 Ibn Battuta, The Travels of Ibn Battuta (Translated by Samuel Lee, 2009), ISBN 978-1-60520-621-9, pp. 97–98

- ↑ Lee 1829, p. 191.

- ↑ Gibb 1971, p. 592 Vol. 3; Defrémery & Sanguinetti 1855, p. 92 Vol. 3; Dunn 2005, pp. 178, 181 Note 26

- 1 2 Aiya 1906, p. 328.

- ↑ Jerry Bently, Old World Encounters: Cross-Cultural Contacts and Exchanges in Pre-Modern Times (New York: Oxford University Press, 1993), 121.

- ↑ Gibb & Beckingham 1994, p. 775 Vol. 4.

- ↑ Defrémery & Sanguinetti 1858, p. 4 Vol. 4.

- ↑ Dunn 2005, p. 238 Note 4.

- ↑ "The Travels of Ibn Battuta: Escape from Delhi to the Maldive Islands and Sri Lanka: 1341–1344". orias.berkeley.edu. Archived from the original on 16 January 2017. Retrieved 12 January 2017.

- ↑ Dunn 2005, p. 215; Gibb & Beckingham 1994, p. 777 Vol. 4

- ↑ Gibb & Beckingham 1994, pp. 773–82 Vol. 4; Dunn 2005, pp. 213–17

- ↑ Gibb & Beckingham 1994, pp. 814–15 Vol. 4

- 1 2 "Ibn Battuta's Trip: Chapter 9 Through the Straits of Malacca to China 1345–1346". The Travels of Ibn Battuta A Virtual Tour with the 14th Century Traveler. Berkeley.edu. Archived from the original on 17 March 2013. Retrieved 14 June 2013.

- ↑ Dunn 2005, p. 258.

- ↑ Dunn 2005, p. 259.

- ↑ Dunn 2005, pp. 259–61

- ↑ Dunn 2005, p. 282

- ↑ Dunn 2005, pp. 283–84

- ↑ Dunn 2005, pp. 286–87

- ↑ Defrémery & Sanguinetti 1858, p. 376 Vol. 4; Levtzion & Hopkins 2000, p. 282; Dunn 2005, p. 295

- ↑ Defrémery & Sanguinetti 1858, pp. 378–79 Vol. 4; Levtzion & Hopkins 2000, p. 282; Dunn 2005, p. 297

- ↑ Levtzion & Hopkins 2000, p. 457.

- ↑ Defrémery & Sanguinetti 1858, p. 385 Vol. 4; Levtzion & Hopkins 2000, p. 284; Dunn 2005, p. 298

- ↑ Hunwick 1973.

- ↑ Jerry Bently, Old World Encounters: Cross-Cultural Contacts and Exchanges in Pre-Modern Times (New York: Oxford University Press, 1993), 131.

- ↑ Defrémery & Sanguinetti 1858, p. 430 Vol. 4; Levtzion & Hopkins 2000, p. 299; Gibb & Beckingham 1994, pp. 969–970 Vol. 4; Dunn 2005, p. 304

- ↑ Dunn 2005, p. 304.

- ↑ Defrémery & Sanguinetti 1858, pp. 425–26 Vol. 4; Levtzion & Hopkins 2000, p. 297

- ↑ Defrémery & Sanguinetti 1858, pp. 432–36 Vol. 4; Levtzion & Hopkins 2000, p. 299; Dunn 2005, p. 305

- ↑ Defrémery & Sanguinetti 1858, pp. 444–445 Vol. 4; Levtzion & Hopkins 2000, p. 303; Dunn 2005, p. 306

- ↑ Noel King (ed.), Ibn Battuta in Black Africa, Princeton 2005, pp. 45–46. Four generations before Mansa Suleiman who died in 1360 CE, his grandfather's grandfather (Saraq Jata) had embraced Islam.

- ↑ M-S p. ix.

- ↑ p. 310

- ↑ Dunn 2005, pp. 310–11; Defrémery & Sanguinetti 1853, pp. 9–10 Vol. 1

- 1 2 Battutah, Ibn (2002). The Travels of Ibn Battutah. Picador. p. 141. ISBN 978-0-330-41879-9.

- ↑ Dunn 2005, pp. 313–14; Mattock 1981

- ↑ Dunn 2005, pp. 63–64; Elad 1987

- ↑ Dunn 2005, p. 179; Janicsek 1929

- ↑ Dunn 2005, p. 134 Note 17

- ↑ Dunn 2005, p. 180 Note 23

- ↑ Dunn 2005, p. 157 Note 13

- ↑ Kamala Visweswaran (2011). Perspectives on Modern South Asia: A Reader in Culture, History, and Representation. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 164–. ISBN 978-1-4051-0062-5. Archived from the original on 19 January 2017.

- ↑ Dunn 2005, pp. 253, 262 Note 20

- ↑ Ralf Elger; Yavuz Köse (2010). Many Ways of Speaking about the Self: Middle Eastern Ego-documents in Arabic, Persian, and Turkish (14th–20th Century). Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. pp. 79–82. ISBN 978-3-447-06250-3. Archived from the original on 11 December 2017.

- ↑ Stewart Gordon (2009). When Asia was the World. Perseus Books Group. pp. 114–. ISBN 978-0-306-81739-7.

- ↑ Michael N. Pearson (2003). The Indian Ocean. Routledge. p. 112. ISBN 978-1-134-60959-8.

He had a son to a Moroccan woman/wife in Damascus ... a daughter to a slave girl in Bukhara ... a daughter in Delhi to a wife, another to a slave girl in Malabar, a son in the Maldives to a wife ... in the Maldives at least he divorced his wives before he left.

- ↑ William Dalrymple (2003). City of Djinns: A Year in Delhi. Penguin Publishing Group. ISBN 978-1-101-12701-8.

- ↑ Kate S. Hammer (1999). The Role of Women in Ibn Battuta's Rihla. Indiana University. p. 45.

- ↑ Gibb 1958, pp. 480–81; Dunn 2005, p. 168

- ↑ Gibb 1958, pp. ix–x Vol. 1; Dunn 2005, p. 318

- ↑ Defrémery & Sanguinetti 1853, Vol. 1 pp. xiii–xiv; Kosegarten 1818.

- ↑ Apetz 1819.

- ↑ de Sacy 1820.

- ↑ Burckhardt 1819, pp. 533–37 Note 82; Defrémery & Sanguinetti 1853, Vol. 1 p. xvi

- ↑ Lee 1829.

- ↑ de Slane 1883–1895, p. 401.

- ↑ MS Arabe 2287; MS Arabe 2288; MS Arabe 2289; MS Arabe 2290; MS Arabe 2291.

- ↑ Dunn 2005, p. 4.

- ↑ Defrémery & Sanguinetti 1853, Vol. 1 p. xxiii.

- ↑ de Slane 1843b; MS Arabe 2291

- ↑ de Slane 1843a.

- ↑ Defrémery & Sanguinetti 1853; Defrémery & Sanguinetti 1854; Defrémery & Sanguinetti 1855; Defrémery & Sanguinetti 1858

- ↑ Defrémery & Sanguinetti 1853, Vol. 1 p. xvii.

- ↑ Gibb 1929.

- ↑ Gibb & Beckingham 1994, p. ix.

- ↑ Gibb 1958.

- ↑ Gibb & Beckingham 1994.

Bibliography

- ibn Battuta. H. A. R. Gibb (ed.). Travels.

- Aiya, V. Nagam (1906). Travancore State Manual. Travancore Government press.

- Apetz, Heinrich (1819). Descriptio terrae Malabar ex Arabico Ebn Batutae Itinerario Edita (in Latin and Arabic). Jena: Croecker. OCLC 243444596.

- Burckhardt, John Lewis (1819). Travels in Nubia. London: John Murray. OCLC 192612.

- Chittick, H. Neville (1977), "The East Coast, Madagascar and the Indian Ocean", in Oliver, Roland (ed.), Cambridge History of Africa Vol. 3. From c. 1050 to c. 1600, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 183–231, ISBN 978-0-521-20981-6.

- Defrémery, C.; Sanguinetti, B.R., eds. (1853), Voyages d'Ibn Batoutah (Volume 1) (in French and Arabic), Paris: Société Asiatic. The text of these volumes has been used as the source for translations into other languages.

- Defrémery, C.; Sanguinetti, B.R., eds. (1854), Voyages d'Ibn Batoutah (Volume 2) (in French and Arabic), Paris: Société Asiatic.

- Defrémery, C.; Sanguinetti, B.R., eds. (1855), Voyages d'Ibn Batoutah (Volume 3) (in French and Arabic), Paris: Société Asiatic.

- Defrémery, C.; Sanguinetti, B.R., eds. (1858), Voyages d'Ibn Batoutah (Volume 4) (in French and Arabic), Paris: Société Asiatic.

- Dunn, Ross E. (2005), The Adventures of Ibn Battuta, University of California Press, ISBN 978-0-520-24385-9. First published in 1986, ISBN 0-520-05771-6.

- Elad, Amikam (1987), "The description of the travels of Ibn Baṭūṭṭa in Palestine: is it original?", Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society, 119 (2): 256–72, doi:10.1017/S0035869X00140651, S2CID 162501637.

- Gibb, H.A.R., ed. (1929), Ibn Battuta Travels in Asia and Africa, London: Routledge. Reissued several times. Extracts are available on the Fordham University site.

- Gibb, H.A.R., ed. (1958), The Travels of Ibn Baṭṭūṭa, A.D. 1325–1354 (Volume 1), London: Hakluyt Society.

- Gibb, H.A.R., ed. (1962), The Travels of Ibn Baṭṭūṭa, A.D. 1325–1354 (Volume 2), London: Hakluyt Society.

- Gibb, H.A.R., ed. (1971), The Travels of Ibn Baṭṭūṭa, A.D. 1325–1354 (Volume 3), London: Hakluyt Society.

- Gibb, H.A.R.; Beckingham, C.F., eds. (1994), The Travels of Ibn Baṭṭūṭa, A.D. 1325–1354 (Volume 4), London: Hakluyt Society, ISBN 978-0-904180-37-4. This volume was translated by Beckingham after Gibb's death in 1971. A separate index was published in 2000.

- Hrbek, Ivan (1962), "The chronology of Ibn Battuta's travels", Archiv Orientální, 30: 409–86.

- Hunwick, John O. (1973), "The mid-fourteenth century capital of Mali", Journal of African History, 14 (2): 195–208, doi:10.1017/s0021853700012512, JSTOR 180444, S2CID 162784401.

- Janicsek, Stephen (1929), "Ibn Baṭūṭṭa's journey to Bulghàr: is it a fabrication?" (PDF), Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society, 61 (4): 791–800, doi:10.1017/S0035869X00070015, S2CID 163430554.

- Kosegarten, Johann Gottfried Ludwig (1818). De Mohamedde ebn Batuta Arabe Tingitano ejusque itineribus commentatio academica (in Latin and Arabic). Jena: Croecker. OCLC 165774422.

- Lee, Samuel (1829). The travels of Ibn Batuta: translated from the abridged Arabic manuscript copies, preserved in the Public Library of Cambridge. With notes, illustrative of the history, geography, botany, antiquities, &c. occurring throughout the work (PDF). London: Oriental Translation Committee. p. 191. Retrieved 5 December 2017. A translation of an abridged manuscript. The text is discussed in Defrémery & Sanguinetti (1853) Volume 1 pp. xvi–xvii.

- Levtzion, Nehemia; Hopkins, John F.P., eds. (2000), Corpus of Early Arabic Sources for West Africa, New York: Marcus Weiner Press, ISBN 978-1-55876-241-1. First published in 1981. pp. 279–304 contain a translation of Ibn Battuta's account of his visit to West Africa.

- Mattock, J.N. (1981), "Ibn Baṭṭūṭa's use of Ibn Jubayr's Riḥla", in Peters, R. (ed.), Proceedings of the Ninth Congress of the Union Européenne des Arabisants et Islamisants: Amsterdam, 1st to 7th September 1978, Leiden: Brill, pp. 209–218, ISBN 978-90-04-06380-8.

- "MS Arabe 2287 (Supplément arabe 909)". Bibliothèque de France: Archive et manuscrits. Retrieved 14 November 2014.

- "MS Arabe 2288 (Supplément arabe 911)". Bibliothèque de France: Archive et manuscrits. Retrieved 14 November 2014.

- "MS Arabe 2289 (Supplément arabe 910)". Bibliothèque de France: Archive et manuscrits. Retrieved 14 November 2014.

- "MS Arabe 2290 (Supplément arabe 908)". Bibliothèque de France: Archive et manuscrits. Retrieved 14 November 2014.

- "MS Arabe 2291 (Supplément arabe 907)". Bibliothèque de France: Archive et manuscrits. Retrieved 14 November 2014.

- Peacock, David; Peacock, Andrew (2008), "The enigma of 'Aydhab: a medieval Islamic port on the Red Sea coast", International Journal of Nautical Archaeology, 37: 32–48, doi:10.1111/j.1095-9270.2007.00172.x, S2CID 162206137.

- de Sacy, Silvestre (1820). "Review of: De Mohamedde ebn Batuta Arabe Tingitano". Journal des Savants (15–25).

- de Slane, Baron (1843a). "Voyage dans la Soudan par Ibn Batouta". Journal Asiatique. Series 4 (in French). 1 (March): 181–240.

- de Slane, Baron (1843b). "Lettre á M. Reinaud". Journal Asiatique. Series 4 (in French). 1 (March): 241–46.

- de Slane, Baron (1883–1895). Département des Manuscrits: Catalogue des manuscrits arabes (in French). Paris: Bibliothèque nationale.

- Taeschner, Franz (1986) [1960]. "Akhī". The Encyclopaedia of Islam. Volume 1: A–B. Leiden: Brill. pp. 321–23.

- Yule, Henry (1916), "IV. Ibn Battuta's travels in Bengal and China", Cathay and the Way Thither (Volume 4), London: Hakluyt Society, pp. 1–106. Includes the text of Ibn Battuta's account of his visit to China. The translation is from the French text of Defrémery & Sanguinetti (1858) Volume 4.