| The Paper | |

|---|---|

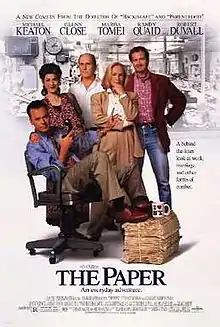

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Ron Howard |

| Written by | |

| Produced by | |

| Starring | |

| Cinematography | John Seale |

| Edited by | |

| Music by | Randy Newman |

Production company | |

| Distributed by | Universal Pictures |

Release date |

|

Running time | 112 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Box office | $48.4 million[1] |

The Paper is a 1994 American comedy-drama film directed by Ron Howard and starring Michael Keaton, Glenn Close, Marisa Tomei, Randy Quaid and Robert Duvall. It received an Academy Award nomination for Best Original Song for "Make Up Your Mind", which was written and performed by Randy Newman.

The film depicts a hectic 24 hours in a newspaper editor's professional and personal life. The main story of the day is two businessmen found murdered in a parked car in New York City. The reporters discover a police cover-up of evidence that the teenage suspects in custody are innocent, and rush to scoop the story in the midst of professional, private and financial chaos.

Plot

The film takes place during a 24-hour period. Henry Hackett is the workaholic metro editor of the New York Sun, a fictional[2] New York City tabloid, who loves his job but the long hours and low pay are leading to discontent. He is at risk of the same fate as his editor-in-chief, Bernie White, who put his work first at the expense of his family. Bernie reveals to Henry that he has been diagnosed with prostate cancer, and tries to track down his estranged daughter Deanne in an attempt to reconcile before his time is up.

The paper's owner Graham Keighley faces dire financial straits, so he has managing editor Alicia Clark, Henry's nemesis, impose unpopular cutbacks, as she schemes to get a raise in her salary. Alicia is also having an affair with Sun reporter Carl. Henry's wife Martha, a Sun reporter on leave and about to give birth, is fed up because Henry seems to have less and less time for her, and she dislikes Alicia. She urges him to seriously consider an offer to leave the Sun and become an assistant managing editor at the New York Sentinel (based on The New York Times), which would mean more money and respectability for shorter hours, but may also be too boring for his tastes.

A hot story is circulating the city, involving the murder of two white businessmen in Williamsburg, Brooklyn. Two African-American teenagers are arrested for the crime, which both Henry and Sun columnist Michael McDougal believe to be false charges when they overhear the NYPD discuss the arrest on the Sun office's police scanner. Henry becomes obsessed with the case, getting others from the Sun staff to investigate along with him.

Henry blows his job offer at the Sentinel by stealing information about the case from the editor's notes while being interviewed for the job, reporting it during a Sun staff meeting. In the meeting, Alicia argues with Henry for them to publish the wrong headline about the suspects today, “Gotcha!”, and print a correction tomorrow if they need to. Bernie gives Henry until 8 o’clock to find more evidence of the teenagers’ innocence.

Martha discovers through her friend in the Justice Department that the businessmen were bankers who stole a large sum of money from their largest investor, a trucking company with ties to the Mafia. Henry begins to believe that it was a setup and the Brooklyn boys were likely just caught in the midst of it.

Henry leaves a dinner with Martha and his parents to go to the police station with McDougal to confirm that the boys were not responsible before they print the story. They corner McDougal's police contact Richie, who, through repeated interrogation and the promise of anonymity, admits that the kids are indeed innocent and just happened to be walking by the scene of the crime when they were caught. Henry and McDougal race back to the Sun office to discover that Alicia has approved the paper's original front-page headline and story stating that the teens were guilty. This results in a physical and verbal fight between Henry and Alicia when he tries to stop the presses printing the papers with the wrong information.

Bernie, Alicia and McDougal end up at the same bar. Alicia has a change of heart about the headline after considering comments made by Henry and McDougal, and she makes a call to stop the printing press. McDougal is attacked by an angry city official named Sandusky, whom McDougal's column had been tormenting for the past several weeks. Their drunken confrontation leads to Sandusky shooting Alicia in the leg, through a wall.

When Henry arrives home, Martha is being rushed to the hospital for an emergency caesarean section due to uterine hemorrhaging. Alicia is brought to the same hospital, where she is able to call the Sun office, has the print room stop the run, and the headline is corrected to Henry's suggestion, "They Didn't Do It", with McDougal's story, just in time for the following morning's circulation. The movie ends with Martha giving birth to a healthy baby boy, and a morning news radio report states that because of the Sun's exclusive story, the Brooklyn teens were released from jail with no charges pressed.

Cast

- Michael Keaton as Henry Hackett

- Robert Duvall as Bernie White

- Glenn Close as Alicia Clark

- Marisa Tomei as Martha Hackett

- Randy Quaid as McDougal

- Jason Robards as Graham Keightley

- Jason Alexander as Marion Sandusky

- Spalding Gray as Paul Bladden

- Catherine O'Hara as Susan

- Lynne Thigpen as Janet

- Jack Kehoe as Phil

- Roma Maffia as Carmen

- Clint Howard as Ray Blaisch

- Michael P. Moran as Chuck

- Geoffrey Owens as Lou

- Amelia Campbell as Robin

- Jill Hennessy as Deanne White

- William Prince as Henry's father

- Augusta Dabney as Henry's mother

- Bruce Altman as Carl

- Jack McGee as Wilder

- Bobo Lewis as Anna

- Edward Hibbert as Jerry

Production

Screenwriter Stephen Koepp, a senior editor at Time magazine, collaborated on the screenplay with his brother David and together they initially came up with "A Day in the Life of a Paper" as their premise. David said, "We wanted a regular day, though this is far from regular."[3] They also wanted to "look at the financial pressures of a paper to get on the street and still tell the truth."[3] After creating the character of a pregnant reporter (played by Marisa Tomei in the film) who is married to the metro editor, both of the Koepps' wives became pregnant. Around that time, Universal Pictures greenlighted the project.

For his next project after Far and Away, Ron Howard was looking to do something on the newspaper industry. Steven Spielberg recommended that he get in touch with David Koepp. Howard intended to pitch an idea to the writer, who instead wanted to talk about how much he loved the script for Parenthood. The filmmaker remembers, "I found that pretty flattering, of course, so I asked about the subject of his work-in-progress. The answer was music to my ears: 24 hours at a tabloid newspaper."[4] Howard read their script and remembers, "I liked the fact that it dealt with the behind-the-scenes of headlines. But I also connected with the characters trying to cope during this 24-hour period, desperately trying to find this balance in their personal lives, past and present."[5]

To prepare for the film, Howard made several visits to the New York Post and Daily News (which would provide the inspiration for the fictional newspaper in the film). He remembers, "You'd hear stuff from columnists and reporters about some jerk they'd worked with ... I heard about the scorned female reporter who wound up throwing hot coffee in some guy's crotch when she found out he was fooling around with someone else."[6] It was these kinds of stories that inspired Howard to change the gender of the managing editor that Glenn Close would later play. Howard felt the Koepps' script featured a newsroom that was too male-dominated.[7] The writers agreed and changed the character's name from Alan to Alicia but kept the dialogue the same. According to David Koepp, "Anything else would be trying to figure out, 'How would a woman in power behave?' And it shouldn't be about that. It should be about how a person in power behaves, and since that behavior is judged one way when it's a man, why should it be judged differently if it's a woman?"[7]

Howard met with some of the top newspapermen in New York, including former Post editor Pete Hamill and columnists Jimmy Breslin and Mike McAlary (who inspired Randy Quaid's character in the movie). They told the filmmaker how some reporters bypass traffic jams by putting emergency police lights on their cars (a trick used in the movie). Hamill and McAlary also can be seen in cameos.[6]

Howard wanted to examine the nature of tabloid journalism. "I kept asking, 'Are you embarrassed to be working at the New York Post? Would you rather be working at The Washington Post or The New York Times?' They kept saying they loved the environment, the style of journalism."[6] The model for Keaton's character was the Daily News' metro editor Richie Esposito. Howard said, "He was well-dressed but rumpled, mid-to-late 30s, overworked, very articulate and fast-talking. And very, very smart. When I saw him, I thought, that's Henry Hackett. As written."[4]

The director also was intrigued by the unsavory aspect of these papers. "They were interested in celebrities who were under investigation or had humiliated themselves in some way. I could see they would gleefully glom onto a story that would be very humiliating for someone. They didn't care about that. If they believed their source, they would go with it happily."[6]

In addition to being influenced by Ben Hecht and Charles MacArthur's famous stage play The Front Page, Howard studied old newspaper movies from the 1930s and 1940s. Howard said, "Every studio made them, and then they kind of vanished. One of the reasons I thought it would make a good movie today is that it feels fresh and different."[8]

One of Howard's goals was to cram in as much information about a 24-hour day in the newspaper business as humanly possible. He said, "I'm gonna get as many little details right as possible: a guy having to rewrite a story and it bugs the hell out of him, another guy talking to a reporter on the phone and saying, 'Well, it's not Watergate for God's sake.' Little, tiny – you can't even call them subplots – that most people on the first screening won't even notice, probably. It's just sort of newsroom background.'"[9]

Reception

Box office

The Paper was given a limited release in five theaters on March 18, 1994 where it grossed $175,507 on its opening weekend. It expanded its release the following weekend to 1,092 theaters where it made $7 million over that weekend. The film went on to gross $38.8 million in the United States and Canada and $9.6 million in the rest of the world for a total of $48.4 million worldwide.[1]

Critical response

The Paper received positive reviews from critics and holds an 89% rating on Rotten Tomatoes based on 35 reviews; the average rating is 7.00/10. The consensus states: "Fast and frenetic, The Paper captures the energy of the newsroom thanks to its cast and director on first-rate form."[10] On Metacritic, the film has a score of 70 out of 100 based on 30 critics, indicating "generally favorable reviews".[11] Audiences surveyed by CinemaScore gave the film an average grade of "B+" on a scale of A+ to F.[12]

In his review for The Boston Globe, Jay Carr wrote, "It takes a certain panache to incorporate the ever-present threat of your own extinction into the giddy tradition of the newspaper comedy, but The Paper pulls it off. There's no point pretending that I'm objective about this one. I know it's not Citizen Kane, but it pushes my buttons".[13] Peter Stack of the San Francisco Chronicle wrote, "In the end, The Paper offers splashy entertainment that's a lot like a daily newspaper itself – hot news cools fast."[14] Entertainment Weekly gave the film a "B" rating and Owen Gleiberman praised Michael Keaton's performance: "Keaton is at his most urgent and winning here. His fast-break, neurotic style – owlish stare, motor mouth – is perfect for the role of a compulsive news junkie who lives for the rush of his job", but felt that the film was "hampered by its warmed-over plot, which seems designed to teach Henry and the audience lessons".[15]

In her review for The New York Times, Janet Maslin was critical of the film. "Each principal has a problem that is conveniently addressed during this one-day interlude, thanks to a screenplay (by David Koepp and Stephen Koepp) that feels like the work of a committee. The film's general drift is to start these people off at fever pitch and then let them gradually unveil life's inner meaning as the tale trudges toward resolution."[16] Rita Kempley, in her review for The Washington Post, wrote, "Ron Howard still thinks women belong in the nursery instead of the newsroom. Screenwriters David Koepp of Jurassic Park and his brother Stephen (of Time magazine) are witty and on target in terms of character, but their message in terms of male and female relations is a prehistoric one."[17]

In an interview, New York journalist and author Robert Caro praised The Paper, calling it "a great newspaper movie."[18]

Year-end lists

- 10th – Christopher Sheid, The Munster Times[19]

- Top 10 (listed alphabetically, not ranked) – Mike Mayo, The Roanoke Times[20]

- Honorable mention – Bob Carlton, The Birmingham News[21]

References

- 1 2 "The Paper". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved 2010-03-05.

- ↑ The real New York Sun merged with another paper in 1950, but the film version shares the same masthead. Since the film's release, a new incarnation of the Sun has appeared, also using the masthead.

- 1 2 Schaefer, Stephen (March 27, 1994). "New edition competes with small screen, too". Boston Herald.

- 1 2 Arnold, Gary (March 27, 1994). "Tabloid press gets the Ron Howard touch in The Paper". Washington Times.

- ↑ Uricchio, Marylynn (March 25, 1994). "Opie's Byline: Paper Director Ron Howard was drawn to Keaton's Style, Newsroom's Buzz". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette.

- 1 2 3 4 Kurtz, Howard (March 27, 1994). "Hollywood's Read on Newspapers; For Decades, a Romance With the Newsroom". The Washington Post.

- 1 2 Schwager, Jeff (August 13, 1994). "Out of the Shadows". Moviemaker. Archived from the original on November 14, 2006. Retrieved 2007-04-16.

- ↑ Dowd, Maureen (March 13, 1994). "The Paper Replates The Front Page for the 90's". The New York Times. Retrieved 2010-03-05.

- ↑ Carr, Jay (October 10, 1993). "Director Ron Howard goes to press with The Paper". The Boston Globe.

- ↑ "The Paper (1994)". Rotten Tomatoes.

- ↑ The Paper Reviews, CinemaScore, retrieved 2023-09-01

- ↑ "Search for 'The Paper'". CinemaScore. Archived from the original on 2018-12-20.

- ↑ Carr, Jay (March 25, 1994). "The Paper gets the story right". The Boston Globe.

- ↑ Stack, Peter (March 25, 1994). "Extra! Extra! Paper Really Delivers!". San Francisco Chronicle.

- ↑ Gleiberman, Owen (March 18, 1994). "The Paper". Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved 2010-03-05.

- ↑ Maslin, Janet (March 18, 1994). "A Day With the People Who Make the News". The New York Times. Retrieved 2010-03-05.

- ↑ Kempley, Rita (March 25, 1994). "Stop the Presses! Roll The Cameras! It's The Paper". The Washington Post. Retrieved 2007-05-08.

- ↑ Robbins, Christopher (17 Feb 2016). "Robert Caro Wonders What New York Is Going To Become". The Gothamist. Archived from the original on 4 January 2017. Retrieved 18 February 2016.

... you know there's another movie, called The Paper. ... Robert Duvall [plays] this editor very much like the editor who I said didn't want to hire anyone from the Ivy League ... It's a great newspaper movie.

- ↑ Sheid, Christopher (December 30, 1994). "A year in review: Movies". The Munster Times. Munster, Indiana.

- ↑ Mayo, Mike (December 30, 1994). "The Hits and Misses at the Movies in '94". The Roanoke Times (Metro ed.). p. 1.

- ↑ Carlton, Bob (December 29, 1994). "It Was a Good Year at Movies". The Birmingham News. p. 12-01.