תל חנתון | |

Tel Hanaton | |

Shown within Israel | |

| Location | |

|---|---|

| Region | Galilee |

| Coordinates | 32°47′08″N 35°15′25″E / 32.78556°N 35.25694°E |

| Type | Tell |

| History | |

| Periods | Bronze Age, Iron Age, Crusader period, Ottoman period |

| Cultures | Canaanite, Israelite, Crusader, Arab |

Tel Hanaton (Hebrew: תל חנתון; Arabic: تل بدويه, romanized: Tal Badawiye, lit. 'the nomads' tell') is an archaeological tell situated at the western edge of the Beit Netofa Valley, in the western Lower Galilee region of Israel, 2 km south of the Town of Kfar Manda and 1 km northeast of the kibbutz which took its name, Hanaton.

Etymology

During most of the Late Bronze Age, the region of Canaan was under the control of Egypt, either as provinces and city-states ruled by Egyptian Governors; or by vassal Canaanite kings who paid annual homage (tribute) to the ruling Pharaoh. It is possible that the city was named for Pharaoh Amenhotep IV also known by the name Akhenaten, the founder of a brief period of monotheism (Atenism) from the Eighteenth dynasty of Egypt during 1352-1334 BC. The name Hanaton (pronounced Khanaton) and the name Akhenaten have identical consonants, which in the Semitic languages of the period are more significant than vowels, which may vary.

History

Biblical period

Tel Hanaton is associated with the biblical Hanaton, mentioned in The Book of Joshua in the lands apportioned to the Tribe of Zevulun: "Then the border went around it on the north side of Hannathon, and it ended in the Valley of Jiphthah El." (Joshua 19:14)

The tel rises to 75m above the surrounding valley, part of which represents the stratification layers on which the Bronze Age and later settlements were built on a natural outcrop of rock.

Archaeologists believe the settlement dates to the Middle Bronze Age. The site has easy access to water sources; nearby forested areas for wood; limestone hills to quarry for building materials and tools; fertile surrounding arable land for crops and livestock; the presence of clay for pottery in the muddy earth surrounding the tel caused by seasonal flooding; the natural rock outcrop raised above its surroundings for easy fortification. It was also located on the international trade route of the period - a branch of the Via Maris.

Late Bronze Age (Egyptian period)

The Tel is mentioned as 'Hinnatuna' in the 14th Century BC Amarna Letters of Ancient Egypt, showing the city's importance on a major trade route.

Hinnatuna is referenced in 2 Amarna letters, EA 8, and EA 245 ('EA' stands for 'El Amarna').

In Amarna letter EA 8, king Burna-Buriash of Babylon complains to the Pharaoh about some Babylonian merchants being killed somewhere near the city of 'Hinnatuna of Canaan', and asks him to take measures.[1]

Amarna letter EA 245 is a letter to Pharaoh from Biridiya, a local ruler.[2] It concerns a certain Labayu, who was probably the mayor of Shechem (Šakmu). This Labayu was then in trouble with the Pharaoh, but somehow escaped punishment after being held for a while in Hinnatuna.

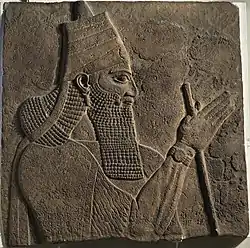

Hanaton is mentioned 700 years later in records at Nineveh, the capital of the Neo-Assyrian Empire as one of five Israelite cities totally destroyed by Tiglath-pileser III, King of Assyria, in the campaign of conquest of the northern Kingdom of Israel between 724-722 BC.

The area of the Bronze Age city reached 100 dunams (approx. 25 acres) which attests to the power and wealth of the settlement, most likely achieved due to the large tracts of highly fertile arable land surrounding the tel in the Beit Netofa Valley, together with its position astride a major 'Egypt to Mesopotamia' international trade route for the period.

Iron Age (Israelite period)

Most Bronze Age tels were forced by increasing populations to expand beyond their hilltops during the Iron (Israelite) age, protected by retaining walls built further out encompassing a greater area. In these cases the former Tel forms the acropolis of the expanded city. Hanaton could not expand in this manner as its immediately surrounding land was subject to months-long flooding following winter rains and drainage technology of the period did not allow for drying up such land.

Restricted in this manner from expansion, the city, whilst never abandoned through to the Roman Period, and unable to expand to the size of Hellenistic period cities, continually declined and was replaced as a major trading and urban centre by nearby Sepphoris which was established on the ridge a few kilometres to the south east.

Early Arab and Crusader periods

During the Early Arab Period, the site became a small agricultural village named Hotsfit, a name which survived into the Crusader Period.

The site shows physical evidence of typical Frankish construction with stone stairwells, large halls and arched ceilings, which may have been part of an 11th-century fortified agricultural settlement together with nearby Sepphoris (also known as Dioceserea). The architecture, whilst having much in common with concurrent strongholds of the Ayyubid period, has distinct Crusader features, such as the arch-free flat-roofed stairwells.

Mamluk period

In the 1330s the region was conquered by the Mamelukes of Egypt, who used the Crusader fort to house their garrison.

Ottoman era

The Arabic name for the tel, Tal Badawiye relates to the Ottoman Period when a Caravanserai named Khan El Badawiye was established atop the tel.

Historical geographer, Victor Guérin, thought that the tel may have been the village Garis mentioned by Josephus in The Jewish War, because of its proximity to Sepphoris.[3]

See also

References

- ↑ Graciela Singer (2014), Fortunes and Misfortunes of Messengers and Merchants in the Amarna Letters.

- ↑ Amarna Tablet 244: Letter from Biridiya of Megiddo to Pharaoh. kchanson.com

- ↑ Guérin, V. (1880). Description Géographique Historique et Archéologique de la Palestine (in French). Vol. 1: Galilée, pt. 1. Paris: L'Imprimerie Nationale., p. 494, who wrote: "...Il ne nous reste donc plus maintenant pour y placer Garis ou Garsis que la colline où sont éparses les ruines de Bir el-Bedaouïeh" (Translation: "...We now have nothing left to place Garis or Garsis here except the hill where the ruins of Bir el-Bedouieh are scattered").