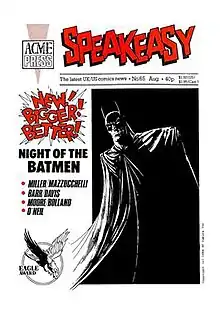

The cover of Speakeasy #65 (August 1986). Artwork by Brian Bolland. | |

| Editor | Richard Ashford (1979–1986) Cefn Ridout (1986) Nigel Curson (1989–1990) Stuart Green (1990–1991) |

|---|---|

| Categories | comics, criticism, history, interviews |

| Frequency | monthly |

| Publisher | Richard Ashford (1979–1986) Acme Press (1986–1989) John Brown Publishing (1989–1991) |

| First issue | Aug. 1979 |

| Final issue Number | May 1991 120 |

| Country | United Kingdom |

| Based in | London |

| Language | English |

Speakeasy was a British magazine of news and criticism pertaining to comic books, comic strips and graphic novels. It published many interviews with both British and American comics creators.[1]

Speakeasy published 120 issues between 1979 and 1991, and won the Eagle Award for Favourite Specialist Comics Publication four times in five years, from 1986 to 1990.

Publication history

Origins

Speakeasy began as a mimeographed fanzine printed on A4 paper, published by Richard Ashford beginning in August 1979. At that point Ashford had already been producing the Fantastic Four Fanzine. By the late 1970s, there were already a number of comics fanzines being published in the U.K., including the long-running Fantasy Advertiser, Martin Lock's BEM, Richard Burton's Comic Media News, Alan Austin's Comics Unlimited, and George Barnett's The Panelologist.[2]

After publishing a second issue in October of that year, Speakeasy went on a year-and-a-half hiatus, until issue #3 was published in June 1981. From that point onward the publication maintained a monthly schedule.

By issue #35 (Nov. 1983) Speakeasy had settled on a permanent logo (which lasted through 1986) and a tagline, "All the latest UK/US comics news". In addition, Ashford had taken on editorial help, with Speakeasy being edited by Bambos Georgiou and Richard Hansom alongside Ashford.

Speakeasy published Alan Moore's comic strip Maxwell the Magic Cat (produced under the pen name "Jill de Ray"), which appeared in most issues published between June 1984 and June 1988. Issue #43 (Oct. 1984) featured another Moore written- and drawn-strip, created under the name "Curt Vile", called Nutters Ruin,[3] which was a previously unsold strip originally produced in 1979.

Speakeasy #53 (Aug. 1985), subtitled "X-Mania", featured interviews with a number of X-Men creators.

Acme Press era

In 1986[4] Ashford, Bambos, Hansom, and Cefn Ridout formed Acme Press as a publishing cooperative to continue producing Speakeasy. Acme would soon branch out into comic book publishing. The Acme Press logo started appearing on the cover with issue #65 (Aug. 1986), which also featured a new Speakeasy logo, designed by Richard Starkings; this logo lasted through issue #101 (Aug. 1989).

By 1986 Ridout was the publication's editor, with Ashford having moved to the editorial board.

With issue #75 (July 1987), Speakeasy changed its logo tagline to "Read about the world of comics in... [Speakeasy]" and became more of a professional magazine than a zine. The June 1988 issue was a double-issue, being numbered #86/87.

Beginning in the summer of 1988, Speakeasy began being distributed in the United States via Eclipse Comics[5] (which had a co-publishing arrangement with Speakeasy's parent company Acme Press).

With issue #95 (Feb. 1989), the magazine introduced a new look (and devoted much of the issue to Tim Burton's Batman film). Issue #95 also featured an interview with Frank Plowright of the United Kingdom Comic Art Convention. The Managing Editor was Ashford, the Features Editor was Hansom, and the News Editor was Nigel Curson. Board members were Ridout, Hansom, Curson, and Ashford. Grant Morrison wrote a column for Speakeasy, titled Drivel, beginning with issue #101 (Aug. 1989).

John Brown Publishing era

John Brown Publishing acquired Speakeasy from Acme Press in late 1989; with issue #106 (Feb. 1990) Rian Hughes redesigned the magazine. The new editor was Nigel Curson.[1][6] Curson left before the end of the year,[3] and his assistant Stuart Green took the editorship. In 1990, after an obscenity raid by British police on a London comic shop, Speakeasy called for a comics legal defense fund.[7]

In April 1990, the magazine sponsored the inaugural Speakeasy Awards, which were presented at the Glasgow Comic Art Convention, held at Glasgow City Chambers, Glasgow, Scotland.[8]

Pressures on Speakeasy around this time included the 1990 debut of a competitor magazine, Dez Skinn's Comics International,[9] and the fact that Speakeasy's sales were limited to comic shops (whereas, say, Comics International was also sold on newsstands).[10]

Speakeasy published its final regular issue, #120, in May 1991; that issue contained the results of the 1990 Speakeasy readers' poll.[11] Speakeasy continued as a 16-page insert in the first five issues of the fellow John Brown Publishing title Blast!,[12][13] but that title itself only lasted seven issues, being cancelled with the November 1991 issue. After Blast!'s cancellation there was some talk of Speakeasy being revived as a free media guide distributed in comic shops and music stores,[14] but it does not appear that ever happened.

Features and columns

- Keep the Home Fires Burning by Mr. M — a column about British comics

- Speak Not Too Harshly; later called Reviewspeak — comics reviews

- Newspeak — UK and US comics industry news; often taking up the bulk of the pages

- Zineseen — zine news & reviews

- Speakout — letter column

- Top Ten — top ten comics lists, selected by a guest creator each issue

- Fandom Confidential — gossip column by "Vikki Veil"

- Drivel by Grant Morrison

Interview subjects (selected)

- Neal Adams (#55, Sept. 1985)

- Mark Badger (#101, Aug. 1989)

- John Byrne (#95, Feb. 1989)

- Chris Claremont (#53, July 1985; part of special issue "X-Mania"; #54, Aug. 1985)

- Dan Green (#53, July 1985) — part of special issue "X-Mania"

- James Hudnall (#63, June 1986)

- Joe Kubert (#57, Dec. 1985)

- Stan Lee (#20, Nov. 1982) — transcript of a 1975 interview with Lee from the Institute of Contemporary Arts' Marvel exhibition

- David Lloyd (#63, June 1986)

- Alan Moore (#54, Aug. 1985; #85, Apr. 1988)

- Grant Morrison (#100, July 1989)[15]

- Dean Mullaney (#52, July 1985)

- Ann Nocenti (#53, July 1985; part of special issue "X-Mania"; #95, Feb. 1989)

- Dennis O'Neil (#95, Feb. 1989) — part of the special issue on Batman

- Jerry Ordway (#95, Feb. 1989)

- John Romita, Jr. (#53, July 1985) — part of special issue "X-Mania"

- Jim Shooter (#71, Feb. 1987)[16]

- Walt Simonson (#35, Nov. 1983; #61, Apr. 1986)

- Dez Skinn (#39, Apr. 1984; #67, Oct. 1986)

- Bryan Talbot (#45 (Sept. 1984)

- Colin Wilson (#63, June 1986)

Awards won

Speakeasy awards

1990

Conducted via a reader's poll and presented at the Glasgow Comic Art Convention, April 1990:[8]

- Best Writer: Grant Morrison

- Best Artist: Dave McKean

- Best Colourist: Steve Oliff

- Best Letterer: Tom Frame

- Best Editor: Karen Berger

- Most Promising Newcomer — Writer: Garth Ennis

- Most Promising Newcomer — Artist: Sean Phillips

- Best Continuing Title: 2000 AD

- Best New Series: The Sandman (DC)

- Best Limited Series: Skreemer (Peter Milligan, Brett Ewins, and Steve Dillon)

- Best Independent Title: A1

- Best One-Shot or Graphic Novel: Arkham Asylum (Grant Morrison and Dave McKean)

- Best Story in a Single Issue: The Sandman (Neil Gaiman)

- Best Continued Storyline: Sláine the Horned God (Pat Mills and Simon Bisley) (2000 AD)

- Best Cover: The Sandman (Dave McKean)

- Best Newspaper Strip: Calvin and Hobbes

- Hype of the Year: Arkham Asylum

- Most Regretted Cancellation: The Shadow

- Biggest Disappointment: Arkham Asylum

1991

Conducted via a reader's poll (about comics published in 1990) and announced in the magazine's final issue, #120 (May 1991):[11]

- Best Writer: Neil Gaiman

- Best Artist: Brendan McCarthy

- Best Ancillary Creator: Steve Whitaker

- Most Promising Newcomer — Writer: Mark Millar

- Most Promising Newcomer — Artist: George Pratt

- Best Continuing Title: The Sandman

- Best New Series: Shade, the Changing Man

- Best Limited Series: Breathtaker

- Best Independent Title: Cerebus

- Best One-Shot or Graphic Novel: Enemy Ace

- Best Translated Comic: Akira

- Best Story in a Single Issue: The Sandman

- Best Continued Storyline: Cerebus

- Best Cover: Doom Patrol #34 (Simon Bisley)

- Best Newspaper Strip: Calvin and Hobbes

- Best Reprint: Little Nemo in Slumberland

- Hype of the Year: Spider-Man

- Most Regretted Cancellation: Revolver

- Biggest Disappointment: Revolver

See also

References

- 1 2 Freeman, John. “WebFinds: Looking back on Speakeasy, a comics magazine that crashed and burned", DownTheTubes.net (FEBRUARY 27, 2014).

- 1 2 Clarke, Theo. "And then nothing happened: THE ESCAPE INTERVIEW", The Comics Journal #122 (June 1988), p. 119.

- 1 2 "READING LIST", The Comics Journal #138 (Oct. 1990), p. 98.

- ↑ Speakeasy #61 (April 1986).

- ↑ CM. "Newswatch: The Comics Journal #123 (July 1988), p. 20.

- ↑ Curson, Natasha. "My year of Speakeasy hell #2", Natasha Curson blog (September 3, 2010).

- ↑ "Newswatch: Censorship Updates", The Comics Journal #139 (Dec. 1990), p. 11.

- 1 2 MCH. "Newswatch: Arkham Leads British Awards", The Comics Journal #137 (Sept. 1990), p. 17.

- ↑ Curson, Natasha. "My year of Speakeasy hell #4", Natasha Curson blog (September 10, 2010).

- ↑ Curson, Natasha. "My year of Speakeasy Hell #5", Natasha Curson blog (September 15, 2010).

- 1 2 "British Awards Announced", The Comics Journal #142 (June 1991), p. 17.

- ↑ "Newswatch: Speakeasy Goes Out with a Blast!", The Comics Journal #140 (Feb. 1991), p. 21.

- ↑ Luke Williams. "Blast! An Early 1990s British News Stand Comics Casualty", DownTheTubes.net (MARCH 25, 2019).

- ↑ "From Hither and Yon...", The Comics Journal #147 (Dec. 1991), p. 27.

- ↑ "NEWSWATCH International: The New Adventures of Hitler: Morrison and Yeowell in Cut Controversy", The Comics Journal #131 (September 1989), p. 11.

- ↑ WDH. "Newswatch: Jim Shooter After Marvel", The Comics Journal #117 (Sept. 1987), p. 16.

- ↑ "English Eagle Awards Announced", The Comics Journal #110 (August 1986), p. 18.

- ↑ Previous Winners: 1987 at the Eagle Awards website, archived at The Wayback Machine. (Retrieved 22 September 2018.)

- ↑ Previous Winners: 1988 at the Eagle Awards website, archived at The Wayback Machine. (Retrieved 22 September 2018.)

- ↑ "Previous Winners: 1990" at the Eagle Awards website, archived at The Wayback Machine.

External links

- Speakeasy at Classic UK Comics Zines

- Speakeasy at MyComicShop.com

- Curson, Natasha. "My year of Speakeasy hell #1" (August 24, 2010)

- Curson, Natasha. "My year of Speakeasy hell #3" (September 7, 2010)