| Southern Mazghuna pyramid | |

|---|---|

| |

| Amenemhat IV(?), 12th Dynasty(?) | |

| Coordinates | 29°45′42″N 31°13′15″E / 29.76167°N 31.22083°E |

| Ancient name | Mazghuna |

| Constructed | 19th-18th century BCE (12th Dynasty-13th Dynasty) |

| Type | True pyramid |

| Material | Mudbrick core (with limestone casing?) |

| Height | 52.5 metres (172 ft) |

Stone ruins of the Southern Mazghuna pyramid (1911) | |

The Southern Mazghuna Pyramid is an ancient Egyptian royal tomb which was built during the 12th or the 13th Dynasty in Mazghuna, 5 km south of Dahshur, Egypt. The building was never finished, and is still unknown which pharaoh was the owner, since no appropriate inscription have been found.

The pyramid was rediscovered in 1910 by Ernest Mackay and excavated in the following year by Flinders Petrie.[1]

Attribution

The building shares some structural similarities to the Hawara pyramid of Amenemhat III, and for this reason it is usually attributed to his son Amenemhat IV (around the end of the 19th-century BCE). In parallel, the near northern Mazghuna pyramid is considered to be the tomb of his sister Sobekneferu, the last ruler of the 12th Dynasty.

However, some researchers such as William C. Hayes[2] believed that the southern pyramid was built during the 13th Dynasty, on the basis of some similarities with the pyramid of Khendjer. In this case, it should have belonged to one of the many pharaohs who ruled between the beginning of the 13th Dynasty and the loss of control of the northern territory occurred during or soon after the reign of Merneferre Ay.[3]

Description

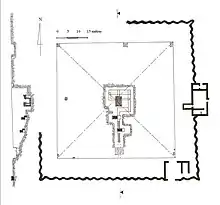

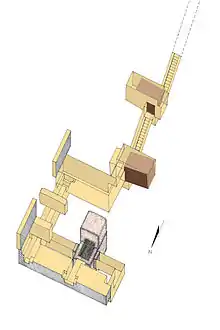

The pyramid has a side length of 52.5 m (172 ft). The core masonry consists of mudbricks and only reaches a height of one to two layers. Casing stones were not found; therefore, it is impossible to determine information about the planned inclination angle and total height.

The entrance of the pyramid is located in the middle of the south side. A staircase leads down to a short horizontal passage. Here is a wall niche, from where a blocking stone had been pushed into the passage. Another staircase leads to a second block, which, however, is still in its niche.

Finally a U-shaped chamber system leads to the burial chamber, which is topped by a gable roof. There was an empty – but used – quartzite sarcophagus and some few grave goods (three limestone lamps, an alabaster duck-shaped vessel, a make-up vessel made from the same material and a piece of polished soapstone) were found in it.

The complex is surrounded by a wavy wall, which incorporate the remains of the chapel in the middle of the east side; it consists of a large central chamber with two chambers on each side of the storehouse. The central chamber was attached in its southwestern corner with a sacrificial hall with a vaulted roof.

The enclosure wall of the complex

The enclosure wall of the complex The chapel of the pyramid complex

The chapel of the pyramid complex Outer limestone blocks and core mud bricks from the pyramid

Outer limestone blocks and core mud bricks from the pyramid Staircase east of the antechamber

Staircase east of the antechamber Staircase to the burial chamber

Staircase to the burial chamber Exterior of the burial vault

Exterior of the burial vault

See also

References

- ↑ Flinders Petrie, G. A. Wainwright, E. Mackay: The Labyrinth, Gerzeh and Mazghuneh, London 1912, available online.

- ↑ W.C. Hayes, The Scepter of Egypt. A Background for the Study of American Antiquites in the Metropolitan Museum of Art. From the Earliest times to the End of the Middle Kingdom, New York, 1953.

- ↑ McCormack, Dawn. "The Significance of Royal Funerary Architecture in the Study of 13th Dynasty Kingship." In M. Marée (ed) The Second Intermediate Period (13th-17th Dynasties), Current Research, Future Prospects, Belgium: Peeters Leuven, 2010, pp. 69-84.

Sources

- Mark Lehner, Das Geheimnis der Pyramiden in Ägypten. Orbis Verlag, München 1999, pp. 184–185, ISBN 3-572-01039-X.

- Rainer Stadelmann, Die ägyptischen Pyramiden. Vom Ziegelbau zum Weltwunder. Verlag Philipp von Zabern, 3. Aufl., Mainz 1997, pp. 250–251, ISBN 3-8053-1142-7

- Miroslav Verner, Die Pyramiden. Rowohlt Verlag, Reinbek 1998, pp. 472–474, ISBN 3-499-60890-1.