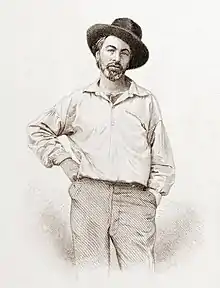

"Song of Myself" is a poem by Walt Whitman (1819–1892) that is included in his work Leaves of Grass. It has been credited as "representing the core of Whitman's poetic vision."[1]

Publication history

The poem was first published without sections[2] as the first of twelve untitled poems in the first (1855) edition of Leaves of Grass. The first edition was published by Whitman at his own expense.

In the second (1856) edition, Whitman used the title "Poem of Walt Whitman, an American," which was shortened to "Walt Whitman" for the third (1860) edition.[1]

The poem was divided into fifty-two numbered sections for the fourth (1867) edition and finally took on the title "Song of Myself" in the last edition (1891–2).[1] The number of sections is generally thought to mirror the number of weeks in the year.[3]

Reception

Following its 1855 publication, "Song of Myself" was immediately singled out by critics and readers for particular attention, and the work remains among the most acclaimed and influential in American poetry.[4] In 2011, writer and academic Jay Parini named it the greatest American poem ever written.[5]

In 1855, the Christian Spiritualist gave a long, glowing review of "Song of Myself", praising Whitman for representing "a new poetic mediumship," which through active imagination sensed the "influx of spirit and the divine breath."[6] Ralph Waldo Emerson also wrote a letter to Whitman, praising his work for its "wit and wisdom".[1]

Public acceptance was slow in coming, however. Social conservatives denounced the poem as flouting accepted norms of morality due to its blatant depictions of human sexuality. In 1882, Boston's district attorney threatened action against Leaves of Grass for violating the state's obscenity laws and demanded that changes be made to several passages from "Song of Myself".[1]

Literary style

The poem is written in Whitman's signature free verse style. Whitman, who praises words "as simple as grass" (section 39) forgoes standard verse and stanza patterns in favor of a simple, legible style that can appeal to a mass audience.[7]

Critics have noted a strong Transcendentalist influence on the poem. In section 32, for instance, Whitman expresses a desire to "live amongst the animals" and to find divinity in the insects.

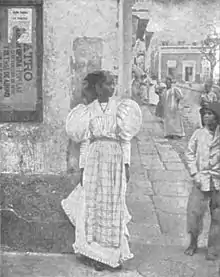

In addition to this romanticism, the poem seems to anticipate a kind of realism that would only become important in United States literature after the American Civil War. In the following 1855 passage, for example, one can see Whitman's inclusion of the gritty details of everyday life:

The lunatic is carried at last to the asylum a confirm'd case,

(He will never sleep any more as he did in the cot in his mother's bed-room;)

The jour printer with gray head and gaunt jaws works at his case,

He turns his quid of tobacco while his eyes blurr with the manuscript;

The malform'd limbs are tied to the surgeon's table,

What is removed drops horribly in a pail;

The quadroon girl is sold at the auction-stand, the drunkard nods by the bar-room stove, ... (section 15)

"Self"

In the poem, Whitman emphasizes an all-powerful "I" which serves as narrator, who should not be limited to or confused with the person of the historical Walt Whitman. The persona described has transcended the conventional boundaries of self: "I pass death with the dying, and birth with the new-washed babe .... and am not contained between my hat and boots" (section 7).

There are several other quotes from the poem that makes it apparent that Whitman does not consider the narrator to represent a single individual. Rather, he seems to be narrating for all:

- "For every atom belonging to me as good belongs to you." (Section 1)

- "In all people I see myself, none more and not one a barleycorn less/and the good or bad I say of myself I say of them" (Section 20)

- "It is you talking just as much as myself... I act as the tongue of you" (Section 47)

- "I am large, I contain multitudes." (Section 51)

Alice L. Cook and John B. Mason offer representative interpretations of the "self" as well as its importance in the poem. Cook writes that the key to understanding the poem lies in the "concept of self" (typified by Whitman) as "both individual and universal,"[8] while Mason discusses "the reader’s involvement in the poet’s movement from the singular to the cosmic".[9] The "self" serves as a human ideal; in contrast to the archetypal self in epic poetry, this self is one of the common people rather than a hero.[10] Nevertheless, Whitman locates heroism in every individual as an expression of the whole (the "leaf" among the "grass").

Uses in other media

Canadian doctor and long-time Whitman friend Richard Maurice Bucke analyzed the poem in his influential and widely read 1898 book Cosmic Consciousness, as part of his investigation of the development of man's mystic relation to the infinite.

Simon Wilder delivers this poem to Monty Kessler in With Honors. Walt Whitman's work features prominently throughout the film, and Simon Wilder is often referred to as Walt Whitman's ghost.

The poem figures in the plot of the 2008 young adult novel Paper Towns by John Green.[11]

A documentary project, Whitman Alabama, featured residents of Alabama reading Whitman verses on camera.[12][13]

The poem is central to the plot of the play I and You by Lauren Gunderson.[14]

"Song of Myself" was a major inspiration for the symphonic metal album Imaginaerum (2011) by Nightwish, as well as the fantasy film based on that album.

The protagonist of the film Nine Days (2020) recites selections of the poem at its conclusion.

See also

- "I Contain Multitudes", a 2020 Bob Dylan song

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 Greenspan, Ezra, ed. Walt Whitman’s "Song of Myself": A Sourcebook and Critical Edition. New York: Routledge, 2005. Print.

- ↑ Loving, Jerome. Walt Whitman: The Song of Himself. California: University of California Press, 1999. Print.

- ↑ Graves, P. "Whitman's "Song of Myself"" (PDF). Englishwithmrsgraves.weebly.com. Retrieved 27 April 2015.

- ↑ Gutman, Huck. "Walt Whitman's 'Song of Myself'". The Oxford Encyclopedia of American Literature. Ed. Jay Parini. Oxford University Press, 2004. Oxford Reference Online. Oxford University Press. Web. 20 October 2011

- ↑ Parini, Jay (March 11, 2011). "The 10 best American poems". The Guardian. Retrieved October 31, 2017.

- ↑ Reynolds, David S. Walt Whitman’s America: A Cultural Biography. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1995. Print.

- ↑ Redding, Patrick. "Whitman Unbound: Democracy and Poetic Form". New Literary Theory 41.3 (2010): 669-90. Project Muse. Web. 19 October 2011.

- ↑ Cook, Alice L. "A Note on Whitman’s Symbolism in 'Song of Myself'". Modern Language Notes 65.4 (1950): 228-32. JSTOR. Web. 17 October 2011

- ↑ Mason, John B. "Walt Whitman's Catalogues: Rhetorical Means for Two Journeys in 'Song of Myself'". American Literature 45.1 (1973): 34-49. JSTOR. Web. 17 October 2011.

- ↑ Miller, James E. Walt Whitman. New York: Twayne Publishers, 1962. Print.

- ↑ Christine Poolos (15 December 2014). John Green. The Rosen Publishing Group, Inc. p. 41. ISBN 978-1-4777-7904-0.

- ↑ "Whitman, Alabama | "Song of Myself" Documentary Series". Whitmanalabama.com. Retrieved 23 May 2022.

- ↑ "Reciting Walt Whitman at a Drug Court in Alabama". The New Yorker. 20 March 2017. Retrieved 23 May 2022.

- ↑ Lauren Gunderson (20 December 2018). I and You. Bloomsbury Publishing. p. 67. ISBN 978-1-350-10510-2.

External links

- The University of Toronto's full text, with line numbers

- Emerson's letter To Whitman

- Alice L. Cook's "A Note on Whitman's Symbolism in 'Song of Myself'"

- John B. Mason's "Walt Whitman's Catalogues: Rhetorical Means for Two Journeys in "Song of Myself"

- WhitmanWeb's full text in 12 languages, plus audio recordings and commentaries

- Audio: Robert Pinsky reads from "Song of Myself" Archived 2019-07-31 at the Wayback Machine

Song of Myself public domain audiobook at LibriVox (individual sections)

Song of Myself public domain audiobook at LibriVox (individual sections) Leaves of Grass public domain audiobook at LibriVox

Leaves of Grass public domain audiobook at LibriVox