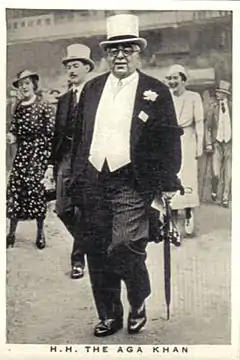

The Simla Deputation was a gathering of 35[note 1] prominent Indian Muslim leaders led by the Aga Khan III at the Viceregal Lodge in Simla in October 1906. The deputation aimed to convince Lord Minto, then Viceroy of india, to grant Muslims greater representation in politics.

The deputation took advantage of the liberal values of the newly-appointed Minto and his Secretary of State, John Morley, following the election of the Liberals in the 1906 United Kingdom general election, as well as the willingness of the British and the Indian Muslims to cooperate – the British wanted to use Indian Muslims as a bulwark against the Indian National Congress and Hindu nationalism, while the Muslims, based in Aligarh Muslim University, wanted to use the opportunity to secure more political representation for themselves.

Minto, finding himself sympathetic to the demands of the Muslims, put many of them into law through the Indian Councils Act 1909, granting the wishes of the deputation. The deputation also led indirectly to the creation of the All-India Muslim League in December that year, as the leaders of the Simla Deputation had taken the time to draft the constitution of the Muslim League to present at the All India Muhammadan Educational Conference.

Background

During the 19th century, Muslim political activism came to be centered on Aligarh Muslim University. The university and its associated Aligarh Movement began to push for Muslim social and educational reform. Its leader, Syed Ahmad Khan, strengthened the Muslim community in northern India by drawing them to his pro-British writings and gatherings.[6] However, his death in 1898 led to the university becoming dormant. However, in the 1900s, the university became heavily involved in politics again, starting with the Hindi-Urdu controversy.[7] The beginning of the 20th century gave rise to the impetus for a Muslim political organization to advocate for Muslims throughout India, much as the Indian National Congress did for India as a whole.[8]

In 1905, Lord Curzon, then Viceroy, reorganized the Bengal Presidency through the Partition of Bengal, splitting the region into East and West Bengal. The partition enraged Hindus,[9] but Muslims, who had become a majority in the newly-formed East Bengal, found themselves opposed to the Hindus. The Muslims of East Bengal, led by Syed Nawab Ali Chowdhury, found an increased power and voice to be used to push for better employment opportunities, education, and political representation. The British found in this Muslim opposition a bulwark against Hindu dominance and nationalism and supported the Muslims.[10]

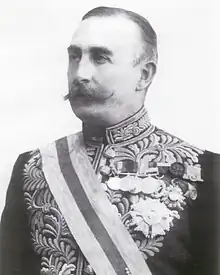

In late 1905, the government of Britain came under the Liberals following the 1906 United Kingdom general election. This coincided with the appointment of Lord Minto, who was more sympathetic to Indian desires for autonomy than his predecessor Lord Curzon, to the position of Vice-Roy following the resignation of Curzon. John Morley, a Liberal MP, was appointed Secretary of State for India in the Liberal government of the UK. Morley made a speech in the UK Parliament in July 1906 hinting at an increase of representation of native Indians in legislative councils for both moderate members of the Indian National Congress as well as Muslims.[11]

Hearing Morley's speech, Muhammad Ismail Khan, a member of the legislative council of the United Provinces, as well as other notable people within politics,[12] wrote to Mohsin-ul-Mulk, successor of Syed Ahmad Khan, suggesting an effort to increase Muslim representation in local councils. Mohsin-ul-Mulk formed a committee to possibly meet the new Viceroy and asked the Principal of Aligarh Muslim University, W.A.J. Archibold, who was in Simla at the time, to pass the committee's request for a meeting on to the Viceroy.[13] The Viceroy agreed, and Syed Hussain Bilgrami drafted the deputation's address with help from Mohsin-ul-Mulk.[12] The address was signed by more than 1182 people and was sent to the Viceroy on 6 September, a month before the deputation itself.[2][note 2]

Historian Peter Hardy argues that the deputation knew that Lord Minto would be somewhat receptive to their requests, or at least that he would not be openly hostile towards them. He argues that this influenced the demands they made towards him.[14]

Deputation

The committee, led by Aga Khan III,[4] went to Simla to meet with Lord Minto on 1 October.[2] The address which had been sent beforehand contained the desires of the deputation – that Muslims, based on their population within India ("numerical strength"), should have a proportionate share of the vote and separate electorates, supported by the idea that having been the rulers of India during the period of the Mughal Empire, Muslims had a higher amount of "political importance".[15][16]

Any kind of representation, direct or indirect, and in all other ways affecting their status and influence, should be commensurate not merely with the numerical strength but also with their political importance.[15]

They also argued that:

Muslims are a distinct community with additional interests [...] which are not shared by other communities and these [...] have not been adequately represented.[4]

Additionally, the deputation did not criticize British rule and only praised it. The deputation also presented the idea that they were satisfied with how things currently were, and that a change was not necessary.[14]

Minto found himself agreeing with the deputation and consenting to many of their demands. He stated that his beliefs aligned with the deputation's members, saying that:

any electoral representation in India would be doomed to mischievous failure which aimed at granting a personal enfranchisement regardless of the beliefs and traditions of the communities composing the population of this continent.[4]

Aftermath

The Simla Deputation managed to convince Lord Minto to create better representation for Muslims within Indian politics – the Indian Councils Act 1909, known as the Morley-Minto or Minto-Morley Reforms, which created non-official Indian majorities in provincial councils, put many of the main demands of the deputation such as separate electorates and separate provincial council seats for Muslims into law.[17][18]

Within the politically active Muslims themselves, the Simla Deputation led to the creation of the All-India Muslim League in December 1906.[19] The Muslim political leaders had previously, while drafting the address to Lord Minto in September, used the opportunity before the next All India Muhammadan Educational Conference later in the year to draft a constitution and set up the foundation of what was to become the Muslim League.[20]

In historiography, the Simla Deputation is referred to by some (such as Hussain) as a landmark within Muslim history in India, as it was the first time Muslims had raised their demands against Hindus on a constitutional level towards the British.[21] Scholarly consensus used to be that the Simla Deputation was something engineered by the British as a way to turn Muslims and Hindus against each other; however, the research of Wasti attempted to show that the deputation had its origins within the Muslim political leaders, and that the British had nothing to do with the address to Lord Minto and the organizing of the deputation.[22]

Notes

- ↑ Sources differ – Some claim the number present was 70,[1] 32,[2] or 30[3] (as well as various other claims), but the most used number among sources is 35 people.[4][5]

- ↑ Sources differ – The address may have been sent after 15–16 September, the date ascribed to the finishing of the draft by a council of political leaders at Lucknow.[12]

References

Citations

- ↑ Purohit 2011, p. 767.

- 1 2 3 Akhtar 2017, p. 767.

- ↑ Lal 1986, p. 73.

- 1 2 3 4 Metcalf & Metcalf 2012, p. 160.

- ↑ Rahman 1970, p. 8.

- ↑ Jones 1989, p. 64.

- ↑ Akhtar 2017, p. 765-6.

- ↑ Malik 2012, p. 171.

- ↑ Metcalf & Metcalf 2012, p. 156.

- ↑ Metcalf & Metcalf 2012, p. 159-60.

- ↑ Akhtar 2017, p. 766-7.

- 1 2 3 Malik 2012, p. 172.

- ↑ Wasti 1976, p. 49.

- 1 2 Akhtar 2017, p. 768.

- 1 2 Panigrahi 2004, p. 45.

- ↑ Akhtar 2017, p. 764.

- ↑ Metcalf & Metcalf 2012, p. 161.

- ↑ Hussain 2010, p. 67.

- ↑ Chaudry 1978, p. 174.

- ↑ Malik 2012, p. 173.

- ↑ Hussain 2010, p. 66.

- ↑ Voigt 1965, p. 73.

Bibliography

Books

- Chaudry, K. C. (1978). Role of Religion in Indian Politics, 1900–1925. Sundeep Prakashan.

- Jones, Kenneth W. (1989). Socio-Religious Reform Movements in British India. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-24986-7.

- Lal, Ramji (1986). Political India, 1935-1942: Anatomy of Indian Politics. Ajanta Publications (India). ISBN 978-81-202-0160-6.

- Metcalf, Barbara D.; Metcalf, Thomas R. (24 September 2012). A Concise History of Modern India. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-02649-0.

- Panigrahi, Devendra (19 August 2004). India's Partition: The Story of Imperialism in Retreat. Routledge. ISBN 1-135-76812-9.

- Rahman, Martiur (1970). From Consultation to Confrontation: a Study of the Muslim League in British Indian Politics, 1906-1912. Luzac. ISBN 978-0-7189-0148-6.

- Wasti, Syed Razi (1976). The Political Triangle in India, 1858-1924. People's Publishing House.

Articles

- Akhtar, Shamim (2017). "Aligarh and Muslim Politics: The Chequered Road to Simla 1875–1906". Proceedings of the Indian History Congress. 78: 762–769. JSTOR 26906150. Retrieved 25 May 2021.

- Hussain, Mahboob (2010). "Muslim Nationalism in South Asia: Evolution Through Constitutional Reforms" (PDF). Journal of Political Studies. 1 (2): 65–77. Retrieved 25 May 2021.

- Malik, Nadeem Shafik (2012). "Formation of the All India Muslim League and Its Response to Some Foreign Issues - 1906-1911" (PDF). Journal of Political Studies. 19 (2): 169–186. Retrieved 25 May 2021.

- Purohit, Teena (May 2011). "Identity Politics Revisited: Secular and 'Dissonant' Islam in Colonial South Asia". Modern Asian Studies. 45 (3): 709–733. doi:10.1017/S0026749X10000181. JSTOR 25835696. S2CID 147171086. Retrieved 25 May 2021.

- Voigt, Johannes H. (April 1965). "Review of Lord Minto and the Indian Nationalist Movement, 1905 to 1910 by Syed Razi Wasti". The Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland. 1 (2): 72–74. doi:10.1017/S0035869X00123895. JSTOR 25202832. S2CID 163860478. Retrieved 25 May 2021.