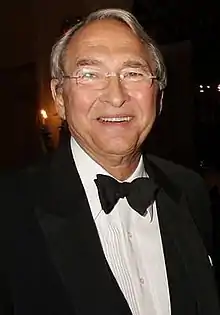

Sheldon Solow | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | July 20, 1928 New York City, U.S. |

| Died | November 17, 2020 (aged 92) New York City, U.S. |

| Occupation | Property developer |

| Spouse | |

| Children | 2, including Stefan Soloviev |

| Website | www |

Sheldon Henry Solow (July 20, 1928 – November 17, 2020) was an American real estate developer and art collector who lived and worked in New York City.[1][2] In August 2020, he had a net worth of $4.4 billion.[3]

Early life

Solow was born and raised in a Jewish family[4] in the Brooklyn borough of New York City.[1] His parents were Isaac, a bricklayer, and Jennie Brill, a homemaker.[3] Solow attended New York University to study engineering and architecture but dropped out in 1949.[5]

Career

Solow acquired his first property, a 72-family apartment building in Far Rockaway, in 1950 with a government-insured loan that his father arranged. He afterwards developed a shopping center as well as homes on Long Island. He established an office in Park Avenue in 1962 around the time that he was developing luxury apartments on Manhattan's Upper East Side.[5]

From 1965, Solow began acquiring property on 57th Street, intending to develop a high-rise residence. To avoid potential problems with holdout properties he acquired the sites secretly using a dummy company, registered in his sister's name. In all, he purchased 14 buildings on 61,800 square feet (5,740 m2) at a cost of $12 million.[5]

In the 1970s, Solow obtained financing,[1] and in collaboration with the architect Gordon Bunshaft, he built a 50-story office building at 9 West 57th Street.[6] One of its prominent features is a large red sculpture of the numeral "9" by Ivan Chermayeff on the sidewalk by the main entrance.[5] Because it had direct views of Central Park, the building was still considered a desirable location into the 21st century.[6]

In the early 2000s, Solow purchased 9.2 acres (3.7 ha) of land along the East River near the United Nations headquarters for $600 million from Consolidated Edison, which included the former site of the Waterside Generating Station and two other parcels.[7] In 2016, he broke ground at one of the sites, 685 First Avenue, to start work on a 42-story residential development designed by Richard Meier.[5] The project was completed in 2018.[8]

Legal actions

Solow was involved in many legal actions and lawsuits during his lifetime. The Real Deal magazine reported in 2008 that, by some measures, he had been involved in "upwards of 200" lawsuits.[9] In 1975, he sued Avon Products, a tenant at 9 West 57th Street, for referring to the structure as the "Avon Building". The case was dismissed but Solow launched further legal action against the company claiming it had failed to restore the building to its original condition at the end of its lease in 1997. The case was settled out of court with Avon paying Solow $6.2 million.[5] Solow sued Peter Kalikow, a friend, over a loan of $7 million that Solow had provided in the mid-1990s. Kalikow had paid back the loan early, depriving Solow of 9 percent interest payments, but the case was dismissed after Solow claimed Kalikow had failed to disclose assets at the time the loan was agreed. In 2006, Solow sued Conseco, the former owner of the General Motors Building, alleging that the $1.4 billion sale of the property by auction had been rigged to exclude him. The case was dismissed in 2009.[5]

Solow had the largest individual loss from the Libor scandal in the U.S., estimated at $500 million. After taking out a loan from Citibank to purchase the Consolidated Edison parcels along the East River to develop a seven-building, $4 billion project, Solow put more than $450 million in high-grade municipal bonds as collateral. However, during the economic downturn of 2008, Citibank artificially inflated the Libor rates, which sank the value of Solow's bond portfolio. On a technicality, Solow defaulted on his loan, which allowed Citibank to seize and sell his bonds and to sue Solow for the value gap of $100 million, a case which Citibank won. In 2012, Solow attempted to sue Citi on the basis of securities fraud, but the case was dismissed. In 2013, Solow sued again, this time over Libor.[10] In April 2019, the New York federal judge ruled in favor of Citibank, and the Libor lawsuit will not be revived.[11]

Personal life and art collection

Solow was married to the sculptor and jewelry designer Mia Fonssagrives-Solow,[12] the daughter of Lisa Fonssagrives, a Swedish model, and the French photographer, Fernand Fonssagrives.[13] They had two children together and lived in New York City.[3] His son, Stefan Soloviev (who uses an older spelling of the family name[3]), now runs Solow Building Co.[14] Stefan also runs an agriculture conglomerate called Crossroads Agriculture based in Colorado and New Mexico. He is ranked the 54th largest landowner in the United States.[3]

Solow was an extensive collector of modernist and renaissance art. Solow owned Young Man holding a Medallion by Botticelli as well as paintings by Balthus, Henri Matisse and Franz Kline, and sculptures by Alberto Giacometti.[1] In February 2012, he sold a Francis Bacon painting for $33.5 million, a Joan Miró painting for $26.6 million, a Henry Moore sculpture for $30.1 million and, in February 2013, he sold an Amedeo Modigliani painting for $42.1 million.[1] In May 2015, he sold Giacometti's 1947 sculpture L'homme au doigt for $126.1 million, setting a world record for the most expensive sculpture ever sold.[15] Though Solow derived significant tax benefit from the collection's 501(c)3 non-profit status, he provided no public access. In 2018, Solow arranged for his son to lead the Solow Art and Architecture Foundation, effectively passing control of the collection from Sheldon to Stefan without any estate tax.[16]

Solow died from lymphoma at Weill Cornell Medical Center in New York on November 17, 2020, at the age of 92.[5]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 Minchom, Clive (August 23, 2013). "Time Waits For No Man : Not Even Sheldon Solow". Jewish Business News.

- ↑ Bagli, Charles V. (March 31, 2010). "Empire Built by Developer Shows Signs of Distress". The New York Times.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Sheldon Solow". Forbes. Retrieved August 13, 2020.

- ↑ "Jewish Billionaires – Profile of Sheldon Solow". Forbes Israel (in Hebrew). April 4, 2013. Archived from the original on September 24, 2015. Retrieved August 14, 2015.

-"New York City real estate bigwigs rank among world's richest Jewish people". The Real Deal. November 11, 2013. - 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Kazakina, Katya; Clark, Patrick; Oster, Patrick (November 17, 2020). "Sheldon Solow, Billionaire Real Estate Developer, Dies at 92". Bloomberg UK. Retrieved November 18, 2020.

- 1 2 Bagli, Charles V. (August 19, 2013). "Prime Lot, Empty for Years (Yes, This Is Manhattan)". The New York Times. Retrieved August 25, 2013.

- ↑ Bagli, Charles V. (August 21, 2005). "Developers Find Newest Frontier on the East Side". The New York Times. Retrieved June 27, 2023.

- ↑ "685 First Ave. in Murray Hill". StreetEasy.

- ↑ Piore, Adam (March 31, 2008). "Solow courts new battles". The Real Deal New York. Retrieved August 16, 2021.

- ↑ Carlyle, Erin (March 28, 2013). "Why Billionaire Sheldon Solow's $450 Million Libor Case Is Likely To Be Followed By More". Forbes. Retrieved July 22, 2020.

- ↑ Koenig, Bryan (April 30, 2019). "2nd Circ. Won't Revive Real Estate Mogul's $100M Libor Suit". Law360. Retrieved July 22, 2020.

- ↑ Barron, James (October 10, 2001). "BOLDFACE NAMES". The New York Times.

- ↑ Havens, Lee. "About Mia". Mia Fonssagrives-Solow. Archived from the original on November 4, 2016. Retrieved February 25, 2015.

- Petkanas, Christopher (August 19, 2011). "Vicky Tiel's 40-Year Career in Fashion". The New York Times. - ↑ "Sheldon Solow". Forbes. Retrieved July 22, 2020.

- ↑ Kazakina, Katya (April 26, 2016). "Deal of the Art: Why Auction Houses Are Giving Away Millions". Bloomberg. Retrieved April 26, 2016.

- ↑ Anuta, Joe (April 23, 2018). "Developer's museum off-limits to the public". Crain's New York Business. Retrieved April 23, 2018.

Rubin, Erin (April 25, 2018). "A Nonprofit Museum with No Public Access: A Showy Extravagance with a Tax Exemption". Non Profit Quarterly. Retrieved April 25, 2018.

External links

- Sheldon Solow on Curbed

- The Solow Foundation - a mock website of Sheldon Solow's art foundation, created in 2017.

1