Sengoi / Sng'oi / Mai Darat | |

|---|---|

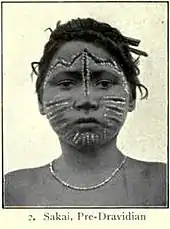

_(14594908837).jpg.webp) Senoi of southern Perak showing face-paint and nose-quill, 1906. | |

| [1] | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Languages | |

| Senoic languages (Semai, Temiar), Southern Aslian languages (Semaq Beri, Mah Meri, Semelai, Temoq), Che Wong, Jah Hut, Malay, English | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Orang Asli (Semang (Lanoh people, Jahai people, Batek people), Proto-Malay (Semelai people, Temoq people)) |

The Senoi (also spelled Sengoi and Sng'oi) are a group of Malaysian peoples classified among the Orang Asli, the indigenous peoples of Peninsular Malaysia. They are the most numerous of the Orang Asli and widely distributed across the peninsula. The Senois speak various branches of Aslian languages, which in turn form a branch of Austroasiatic languages. Many of them are also bilingual in the national language, the Malaysian language (Bahasa Melayu).

Status and identity

The Malaysian government classifies the indigenous people of Peninsular Malaysia as Orang Asli (meaning "indigenous peoples" in Malay). There are 18 officially recognized tribes under the auspices of the Department of Aboriginal Affairs (Jabatan Kemajuan Orang Asli, JAKOA). They are divided into 3 ethnic groups namely, Semang (Negrito), Senoi and Proto-Malays, which consist of 6 tribes each. Such a division is conditional and is based primarily on the convenience of the state to perform administrative functions. The terms "Semang", "Senoi" and "Proto Malays" do not refer to specific ethnic groups or their ethnic identity. For the Orang Asli, they are of external origin. Each of the tribes is completely independent and does not associate itself with any wider ethnic category of the population.

The three ethnic group division of the Orang Asli was developed by British colonizers in the early twentieth century according to early European racial concepts. Due to the fact that the three ethnic groups differ in language, appearance (physical characteristics) and the nature of their traditional economy, Negritos (short, dark, curly) were considered the most primitive race, Senois (taller, with lighter skin, wavy black hair) as more advanced, and Aboriginal Malays (tall, fair-skinned, with straight hair) were perceived almost on an equal footing with Muslim Malays. Later, concepts that are deemed racist were rejected and the categories of Semang, Senoi and Proto-Malay (a Malay term that replaced "Aboriginal Malays") became markers of different models of cultural traditions and specific socio-economic complexes. The Senoi model, in particular, provides for the existence of autonomous communities, whose main means of subsistence are based on slash-and-burn agriculture, which on a small scale is supplemented with hunting, fishing, gathering, and the processing and sale of jungle produce. In this respect, they differ from the Semangs (hunter-gatherers) and the Proto-Malays (settled farmers).

The Senoi people are also known as Sakai people among the locals.[2] For the Malay people, the term sakai is a derogatory term in Malay language and its derivative word menyakaikan means "to treat with arrogance and contempt". However, for the Senoi people mensakai means "to work together".[3] During the colonial British administration, Orang Asli living in the northern Malay Peninsula were classified as Senoi and to a point later it was also a term to refer to all Orang Asli.[4] On the other hand, the Central Senois; particularly of Batang Padang District, prefer to call themselves as Mai Darat in opposed to the term sakai.[5] It is often misunderstood that Senoi people who have abandoned their own language for the Malay language are called the Blandas, Biduanda or Mantra people.[6] The Blandas people are of the Senoi race from Melaka.[7] The Blandas language or Bahasa Blandas, which is a mixture of Malay language and Senoic language;[8] is probably used predating the first arrivals of the Malay people in Melaka.[6]

Tribal groups

Senoi is the largest group of Orang Asli, their share is about 54 percent of the total number of Orang Asli. The Senoi ethnic group includes 6 tribes namely, the Cheq Wong people, the Mah Meri people, the Jah Hut people, the Semaq Beri people, the Semai people and the Temiar people. They are closely related to the Semelai people, one of the tribes classified as part of the Proto-Malays. There is another smaller tribal group, the Temoq people, which ceased to exist in the 1980s when the predecessor of JAKOA included them in the ethnic group.

The criteria used to identify people as Senoi are inconsistent. This group usually includes tribes that speak Central Aslian languages and engage in slash-and-burn agriculture. These criteria are met by the Semai people and Temiar people; the two largest Senoi peoples. But the Senoi also include the Cheq Wong people, whose language is of the North Aslian languages group, the Jah Hut people, whose language occupies a special place among the Aslian languages on its own, and the Semaq Beri people are speakers of the Southern Aslian languages. Culturally, the Senoi also include the Semelai people and Temoq people, who are officially included in the Proto-Malays. At the same time, the Mah Meri people, who according to the official classification are considered to be Senoi, are engaged in agriculture and fishing and are culturally closer to the Malays. The last three peoples speak Southern Aslian languages.

- Cheq Wong people (Chewong, Ceq Wong, Che 'Wong, Ceʔ Wɔŋ, Siwang) are semi-Negritos living in three or four villages on the southern slopes of Mount Benom[9] in remote areas of western Pahang (Raub District[10] and Temerloh District[11]). The ethnological classification of the Cheq Wong people has always been problematic. The name "chewong" is a distortion of the name of a Malay employee in the Department of Hunting, Siwang bin Ahmat before the Second World War period, which the British huntsman misunderstood as the name of an ethnic group.[12] The traditional Che Wong economy was dominated by jungle produce gathering. Their language belongs to the Northern Aslian languages group, it is related to the Semang's languages.

- Temiar people (Northern Sakai, Temer, Təmεr, Ple) are the second largest Senoi people. They are inhabited by 5,200 km of jungle on both sides of the Titiwangsa Mountains, inhabiting southern Kelantan and northeastern Perak.[13] As a rule, they live in the upper reaches of rivers, in the highest and most isolated regions. In the peripheral areas of their ethnic territory they maintain intensive contacts with neighboring peoples. The main traditional occupations are slash-and-burn agriculture and trading.

- Semai people (Central Sakai, Səmay, Səmey) is the largest tribe not only of the Senoi ethnic group, but also of all Orang Asli. They live south of the Temiar people, in separate groups, also on both slopes of the Titiwangsa Mountains in southern Perak, northwestern Pahang, and neighboring areas of Selangor.[13] The main traditional occupations are slash-and-burn agriculture and trading, they are also engaged in the cultivation of commercial crops and labour work. They live in different conditions, from mountainous jungles to urban areas. The Semai people have never had a strong sense of shared identity. Mountain dwelling Semai people refers to their fellow lowland relatives as "Malays"; and they in turn, refers to their fellow mountain dwelling relatives as "Temiars".

- Jah Hut people (Jah Hět, Jah Hət) are located in the Temerloh District and Jerantut District, on the eastern slopes of Mount Benom in central Pahang, the eastern neighbours of the Cheq Wong people.[9] Their traditional occupation includes slash-and-burn agriculture.

- Semaq Beri people (Səmaʔ Bərēh, Semoq Beri) are inhabitants of the interior of Pahang (Jerantut District, Maran District, Kuantan District) and Terengganu (Hulu Terengganu District, Kemaman District).[14] The name Semaq Beri was first given to one of the local groups by the British colonial administrators, and later the name spread to the whole nation. In their language, it means "jungle people".[12] Traditional occupations of the people were slash-and-burn agriculture, hunting and gathering. Divided into settlement groups in the south and groups of former hunter-gatherers who in the past roamed over a large area around Bera Lake in Pahang, as well as in Terengganu and Kelantan. Many other Orang Asli see the Semaq Beri people as Semelai people.

- Semelai people (Səməlay) are located in central Pahang, in particular in the area of Bera Lake, the rivers of Bera District, Teriang, Paya Besar and Paya Badak.[15] They also live on the Pahang border with the Negeri Sembilan (along the rivers of Serting and Sungai Lui, and in the lowlands north of Segamat District to the southern riverbanks of the Pahang River) and on the other side of the border between these states.[15] Officially included in the Proto-Malay population. Jungle gathering was not part of their traditional economic complex. In addition to slash-and-burn agriculture, they fish in lakes and work for hire.

- Temoq people (Təmɔʔ) is a little-known group which currently is not officially recognised by JAKOA, although in the past it was included in its list of ethnic tribes. They are included together with the Semelai people's population, their western neighbours. They live in Pahang, along the Jeram River in northeastern of Bera Lake.[16] Traditionally they are nomads and from time to time engaged in agriculture.[16]

- Mah Meri people (Hmaʔ MərĪh, other obsolete names are Besisi, Besisi, Btsisi', Ma' Betise', Hma' Btsisi') live in the coastal areas of Selangor.[17] In addition to agriculture, engaged in fishing. Among all of the Senoi peoples, the Mah Meri people were most affected by the Malay people. However, they are afraid to live in urban areas, and their commitment to their own customary lands remains very strong.

In the past, there must have been other Senoi tribes. In the upper reaches of the Klau River west of Mount Benum, the mysterious Beri Nyeg or Jo-Ben are mentioned, speaking a language quite closely related to Cheq Wong people. The Jah Chong tribe, which could speak a dialect very different from the Jah Hut people was also reported. Several dialects associated with Besis (Mah Meri people) existed in the Kuala Lumpur area. Perhaps there were other tribes speaking Southern Aslian languages and live in areas that currently inhabited by the Temuan people and Jakun people, speakers of Austronesian languages.[18]

Government development programmes are aimed at the rapid clearing of jungles on mountain slopes. As a result, modern areas of Senoi are becoming increasingly limited.

Demography

.jpg.webp)

The Senoi tribes live in the central region of the Malay Peninsula[19] and consist of six different groups, namely the Semai, Temiar, Mah Meri, Jah Hut, Semaq Beri and the Cheq Wong and have a total population of about 60,000.[20] An example of a typical Senoi (Central Sakai) people, the purest of the Sakai are found in Jeram Kawan, Batang Padang District, Perak.[21]

The available data on the population of individual Senoic tribes are as follows:-

| Year | 1960[22] | 1965[22] | 1969[22] | 1974[22] | 1980[22] | 1982 | 1991[23] | 1993[23] | 1996[22] | 2000[Note 1][24] | 2003[Note 1][24] | 2004[Note 1][25] | 2005 | 2010[1] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Semai people | 11,609 | 12,748 | 15,506 | 16,497 | 17,789 | N/A | 28,627 | 26,049 | 26,049 | 34,248 | 43,892 | 43,927 | N/A | 49,697 |

| Temiar people | 8,945 | 9,325 | 9,929 | 10,586 | 12,365 | N/A | 16,892 | 15,122 | 15,122 | 17,706 | 25,725 | 25,590 | N/A | 30,118 |

| Jah Hut people | 1,703 | 1,893 | 2,103 | 2,280 | 2,442 | N/A | N/A | 3,193 | 3,193 | 2,594 | 5,104 | 5,194 | N/A | 4,191 |

| Cheq Wong people | 182 | 268 | 272 | 215 | 203 | 250[10] | N/A | N/A | 403 | 234 | 664 | 564 | N/A | 818 |

| Mah Meri people | 1,898 | 1,212 | 1,198 | 1,356 | 1,389 | N/A | N/A | 2,185 | 2,185 | 3,503 | 2,986 | 2,856 | 2,200[26] | 2,120 |

| Semaq Beri people | 1,230 | 1,418 | 1,406 | 1,699 | 1,746 | N/A | N/A | 2,488 | 2,488 | 2,348 | 3,545 | 3,345 | N/A | 3,413 |

| Semelai people[Note 2] | 3,238 | 1,391 | 2,391 | 2,874[Note 3] | 3,096[Note 3] | N/A[Note 3] | 4,775[Note 3] | 4,103[Note 3] | 4,103[Note 3] | 5,026[Note 3] | 6,418[Note 3] | 7,198[Note 3] | N/A[Note 3] | 9,228[Note 3] |

| Temoq people[Note 2] | 51 | 52 | 100 | N/A[Note 3] | N/A[Note 3] | N/A[Note 3] | N/A[Note 3] | N/A[Note 3] | N/A[Note 3] | N/A[Note 3] | N/A[Note 3] | N/A[Note 3] | N/A[Note 3] | N/A[Note 3] |

| Total | 28,856 | 28,307 | 32,905 | 35,507 | 39,030 | 250 | 50,294 | 53,140 | 53,543 | 65,659 | 88,334 | 88,674 | 2,200 | 99,585 |

These data come from different sources, therefore, are not always consistent. JAKOA figures, for example, do not take into account of Orang Asli living in cities that do not fall under JAKOA's jurisdiction. Differences in the calculation of Semai people and Temiar people sometimes make up about 10-11%. A significant number of Orang Asli now live in urban areas and their numbers can only be estimated, as they are not recorded separately from the Malays. However, this does not mean that they were assimilated into the Malay community.

Distribution of Senoi peoples by state (JHEOA, 1996 census):-[22]

| Perak | Kelantan | Terengganu | Pahang | Selangor | Negeri Sembilan | Melaka | Johor | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Semai people | 16,299 | 91 | 9,040 | 619 | 26,049 | ||||

| Temiar people | 8,779 | 5,994 | 116 | 227 | 6 | 15,122 | |||

| Jah Hut people | 3,150 | 38 | 5 | 3,193 | |||||

| Cheq Wong people | 4 | 381 | 12 | 6 | 403 | ||||

| Mah Meri people | 2,162 | 12 | 7 | 4 | 2,185 | ||||

| Semaq Beri people | 451 | 2,037 | 2,488 | ||||||

| Semelai people | 2,491 | 135 | 1,460 | 6 | 11 | 4,103 | |||

| Total | 25,082 | 6,085 | 451 | 17,215 | 3,193 | 1,483 | 13 | 21 | 53,543 |

Language

The Senois speak various sub-branches within the Aslian languages of the Austroasiatic languages.

The Aslian languages are divided into four branches namely the Jahaic languages (Northern Aslian languages), the Semelaic languages (Southern Aslian languages), the Senoic languages (Central Aslian languages) and the Jah Hut language. Among the Senoi people, they consists of speakers from all four sub-group languages. The two largest peoples, the Semai people and the Temiar people, speak the Central Aslian languages group, with which they are usually associated with the Senoi. The Jah Hut language was previously also included in the Central Asian languages, but new historical and phonological studies have shown it to be in an isolate position within the Aslian languages.[27] Almost all Senoic and Semelaic branches are spoken by Senoi peoples such as the Semaq Beri language, Semelai language, Temoq language and Mah Meri language which belongs to the Southern Aslian languages group. However, with the exception of the Lanoh people (also known as Sakai Jeram people)[28] which is classified as Semang but speak a branch of Senoic languages[29] and Semelai which is classified as Proto-Malay but speak a branch of Semelaic languages. The Cheq Wong language belongs to the North Aslian languages group, a language group spoken by the Semang; which makes it is very different from the other languages of this sub-ethnic group.[18]

Despite the obvious common features between the Aslian languages, the fact of their common origin from one language is not firmly established.[27]

Semai language, the largest of the Senoi languages,[30] is divided into more than forty distinct dialects,[31] although traditionally only two main dialects are recognised (western or lowland, and eastern or highland), and not all of them are mutually intelligible.[32] Each dialect functions to some extent on its own. A very high level of dialectal division prevents the preservation of the language as a whole.

Temiar language on the other hand is relatively homogeneous with its local variations are mutually intelligible and are perceived only as accents.[33] There is a standardisation and territorial expansion of this language. The peculiarity of the Temiar language is also that it acts as a kind of buffer between other Aslian languages and Malay language. On one hand, this has greatly increased the Temiar vocabulary, creating a high level of synonymy, and on the other hand, it has contributed to the spread of the Temiar language among the neighbouring Orang Asli tribes. It became something like the lingua franca among the northern and central groups of the Orang Asli.[34]

Almost all Orang Asli are now at least bilingual; in addition to their native language, they also speak Malay language, the national language of Malaysia.[35] There is also multilingualism, when people know several Aslian languages and communicate with each other.[36] However the Malay language is gradually displacing native languages, reducing the scope of their use at the domestic level.[37] More and more Orang Asli can read and write, of course, in Malay language. Added to this is the informational and technical impact, which is also in Malay language.

When it comes to the level of threat of extinction for Aslian languages, long-term interactions between these languages as well as with Malay language should be taken into account. Malay lexical borrowings are found in Southern Aslian languages, as well as in the languages of small or interior Orang Asli groups, especially those who lived on the plains and maintained regular contact with the Malay population. For example, in Semelai language it has 23% loan words, and 25% loan words in Mah Meri language. On the other hand, the languages of large agricultural peoples, who lived largely isolated from the Malays, have the least Malay borrowings. For the Temiar language, this figure is only 2%, for the highland Semai dialect it has 5%, and for the lowland Semai dialect it has 7%. Aslian languages have phonetic borrowings from Malay language, but they are often used only in Malay words.

_(14594772779).jpg.webp)

The influence of the Malay language grows with the development of the economy and infrastructure in the areas of Orang Asli and, accordingly, the increase of external contacts. The use of some Aslian languages has greatly diminished, and the Mah Meri language is in the greatest danger among the Senoi languages. Its speakers are in close proximity not only to the Malays, but also to other Orang Asli communities, including the Temuan people, where mixed marriages have taken place, and people switch to another language. The loss of language, however, does not mean the loss of one's own culture.

Most Orang Asli continue to speak their native languages. Some indigenous young people are proud to speak the Aslian language and would regret it if it had disappeared. However, others are ashamed to speak their native language openly.[27][38]

The positions of Semai people and Temiar people, the two largest Aslian languages, remain quite strong. Semai language it serves as a lingua franca in paramilitary detachments Orang Asli- Senoi Praaq.[27] The Temiar language is widespread among many neighboring Orang Asli tribes, and is even known to some Malays in some parts of Kelantan. At the Orang Asli hospital complex in Ulu Gombak District, north of Kuala Lumpur, many patients speak Temiar language,[39] a manifestation of "Aslian" solidarity. Another factor in favor of the Semai and Temiar languages is the emergence of a pan-Aslian identity within the indigenous population of Peninsular Malaysia, as opposed to the Malay majority. The Temiar and Semai languages are special programs for the Orang Asli broadcast by Radio Televisyen Malaysia. Orang Asli radio broadcasting began in 1959 and is now broadcast as Asyik FM daily from 8 a.m. to 10 p.m. The channel is also currently made available online.[40] Semai and Temiar speakers, speaking their native languages, use a significant number of Malay words, especially in news releases. Temiar and Semai are often used together. In the past, there were sometimes speeches in other Aslian languages, including Mah Meri language, but this has stopped. Unfortunately, both major Senoi languages do not have official status in Malaysia.

There are very few written publications in Asian languages.[41] Until recently, none of the Aslian languages had written literature. However, some Baháʼí Faith and Christian missionaries, as well as JAKOA newsletters, produce printed materials in Aslian languages. Texts recorded by radio announcers are based on Malay and English writing and are amateur in nature. Orang Asli value literacy, but they are unlikely to be able to support writing in their native language based on the Malay or English alphabet.[42] Authors of Aslian texts face problems of transcription and spelling, and the influence of the stamps characteristic of the standard Malay language is felt.[42]

Aslian languages have not yet been sufficiently studied, and no qualitative spelling has been developed for them. However, official steps have been taken to introduce Temiar language and Semai language as the languages of instruction in primary schools in Perak.[43] The training materials were prepared by the Semai School Teachers' Committee. In support of this programme, a special "orientation" meeting was held in March 1999 in Tapah.[44] Given the technical difficulties associated, among other things, with the presence of numerous dialects in the Semai language, it is too early to say whether these efforts will be successful. But several schools have already begun to use the Semai language. This was done in accordance with the Education Act 1996 of Malaysia, according to which in any school with about 15 Orang Asli students, their parents can request the opening of classes with their ethnic language of instruction, which they must be provided. The reason for the state's interest in the development of Aslian languages is the irregular attendance of schools by Orang Asli children, which remains a problem for the Malaysian education system.[44]

A new phenomenon is the emergence of text messages in Aslian languages, which are distributed by their speakers when using mobile phones. Unfortunately, due to fears of invasion of privacy, most of these patterns of informal literacy cannot be seen. Another landmark event was the release of recordings of pop music in Aslian languages, mainly in Temiar language and Semai language. They can often be heard on Asyik FM. The commercially successful album was Asli, recorded by an Orang Asli band, Jelmol (Jɛlmɔl, meaning "mountains" in Temiar language).[45] Although most of the songs in the album are performed in Malay language, there are 2 tracks in Temiar language.[45]

History

_(14583642829).jpg.webp)

The Senoi are believed to have arrived on the Malaya Peninsula about 8000 to 6000 B.C during the Middle of the Holocene period, the population of the Malay Peninsula has undergone significant changes in its biological physiognomy, material culture, production skills and language. They were partly caused by the arrival of migrant farmers from the more northern parts of mainland Southeast Asia (Thailand, Cambodia, Vietnam). The arrival of migrants is associated with the emergence of fire-cutting agriculture on the Malay Peninsula and the emergence of rice. As a result of mixing new groups with local Negrito tribes, the ancestors of the Senoi,[46] who lived in the northern and central parts of the peninsula. The introduction of agriculture has led to the semi-permanent residence of related groups, as well as the formation of more stable social structures in their environment. The refusal of constant movement prompted the formation of individual local communities and peoples.

The population of the peninsula is divided into two groups, each with its own stable socio-economic complex, namely Semang and Senoi people. The Semang people lived in dense rain forests located at altitudes below 300 meters above sea level, and were engaged in nomadic hunting and gathering. Senoi lived at higher altitudes and cultivated their agricultural land. Contacts between the two groups were minimal, the Senoi people only exchanged their agricultural produce for jungle gifts.

Migrants from the north brought not only agriculture but also Aslian languages, which are now spoken by both the Senoi and the Semang people.

Early Austronesian migrants arrived on the Malay Peninsula about 2,500 years ago. They were the ancestors of modern Proto-Malays (Jakun people, Temuan people). The Malays arrived later, probably about 1,500 to 2,000 years ago. The Orang Asli tribes were not isolated. Around 500 BC, small coastal settlements appeared on the Malay Peninsula, which became centers of trade and maintained contacts with China, India, Thailand,[47] the Middle East, and the Mediterranean. Orang Asli became suppliers of jungle produce (aromatic wood, rubber, rhino horns and elephant tusks), as well as gold and tin ore, with the latter was especially sought out by Indian traders for the production of bronze. In exchange, the indigenous people of the Malay Peninsula received goods such as fabrics, iron tools, necklaces and food, including rice. Under the influence of external contacts there is another cultural tradition of the indigenous population, characteristic of modern Proto-Malays. There are reports that South Asian languages may be related to modern Mah Meri language or Semelai language, in the past were common in the interiors of Negeri Sembilan, Pahang and Johor. Later they became part of the Jakun people and Temuan people. Thus, the southern groups of Senoi were directly involved in shaping the tradition of the indigenous Proto-Malays.

At the end of the 14th century. on the coast of the Malay Peninsula, the Malays established their trading settlements, the most famous of which was Melaka. At the beginning of the 15th century, the ruler of Malacca converted to Islam. The number of Malays was constantly increasing due to the influx of new migrants from Sumatra and other parts of modern-day Indonesia, as well as the assimilation of the Orang Asli. Malay migrants moved in slowly by rivers into the interior of the peninsula, and most Orang Asli retreated in parallel to the foothills and mountains. The Malay language and culture gradually spread. As the Malay population increased, the political and economic importance of the Orang Asli were diminished. Their numbers also declined, and now the indigenous population that remains are only the minorities that rejected assimilation.

_(14781134312).jpg.webp)

The rise of the Malay states first turned the Senoi people into subordinates and after the establishment of Islam, they were regarded as despised pagans and kafirs.[48][49] The lifestyle of the Orang Asli, their clothing traditions, as well as their physical characteristics among the Malays became the object of ridicule.[50][51] In the 18th and 19th centuries, Orang Asli fell victim to slave raiders, mostly Malays from Sumatra.[50][52] The indigenous people were not Muslims, so they were not banned from being enslaved by other Muslims. Typically, well-armed men attacked a village or camp at night, killing adult men and women and capturing children. Sometimes Malays provoked or forced Orang Asli leaders to abduct people from another group of Orang Asli, whom they handed over to the Malays; in an attempt to protect their own wives from captivity. Enthusiastic slaves formed the labor force both in the cities and in the households of the chiefs and sultans; while others were sold in slave markets to slave traders, who transported them to other lands, including Java. From that time comes the derogatory term "sakai" as used by the Malays for the Senoi people; which means "animal (rough or savages) aborigines" or "slaves".[49][53] Following the British Slavery Abolition Act 1833, slavery was subsequently abolished throughout the British Empire and slave raiding was made illegal by the British colonial government in British Malaya in 1883, although there were records of slave raiding up to the 20th centuries in the 1920s.[52]

The events of the past have sown a deep distrust of the Orang Asli people towards the Malay population. They tried to isolate themselves in remote areas. Only the abolition of slavery has led to the increase of contact with outsiders. The Malayan Emergency of the 1950s in British Malaya accelerated the penetration of the state into the interiors. In an attempt to deprive the Malayan Communist Party of support from the Orang Asli, the British carried out forced relocation of the indigenous people to special camps under the protection of the army and police.[54] They were living in the camps for two years, after which they were allowed to return to the jungle. This event was a severe blow to them, as hundreds of people died in the camps from various diseases.[55] Since then, the government has paid more attention to the Senoi and other indigenous peoples.[55] Then the Department of Aboriginal Affairs, the predecessor of the modern JAKOA was founded in 1954, which was authorized to lead the Orang Asli communities.[55] In 1956, during the struggle against the Malayan Communist Party insurgents, the British colonial authorities created Senoi Praaq detachments (in Semai language, it roughly means "military people"), which served as military intelligence in addition to police functions. They consisted of Orang Asli and operated in the deep jungle. Senoi Praaq units proved to be very effective and their operations were extremely successful in suppressing the communist insurgents. They gained notoriety for their brutality, which surpassed any other unit of the security forces.[56] Today, they are now part of the General Operations Force of the Royal Malaysia Police.[57]

Since the 1980s, there has been an active invasion of Orang Asli areas by individuals, as well as corporations and state governments.[58] Logging and the replacement of jungles for rubber and oil palm plantations have become widespread.[58] These processes gained the greatest scale in the 1990s. These processes severely disrupted the lives of most of the Orang Asli tribes. Without the jungles, former hunter-gatherers no longer have the opportunity to gather wild fruits and hunt wild animals. They have to adapt to a new way of life associated with the monetary economy. The construction of highways and the development of the plantation economy cause the relocation of the indigenous population to cities and new villages, specially built for them by state governments.[52]

there could be no doubt that the Malays were the indigenous people of this country because the original inhabitants did not have any form of civilisation compared with the Malays ..... [These] inhabitants also had no direction and lived like primitives in mountains and jungles

—Tunku Abdul Rahman, Malaysia's first Prime Minister, The Star (Malaysia), 6 November 1986[59]

The government's policy is to convert the indigenous people to Islam[60] and to integrate them into the main population of the country as settled peasants.[61] At the same time, the Orang Asli would prefer to modernise without becoming Malays, even when converting to Islam. After joining the mainstream society, Orang Asli occupy the lowest rungs of the social ladder. Even their status as the first indigenous people of the peninsula is now being challenged on the almost incomprehensible grounds that they were not carriers of "civilisation."[59] The political state in Malaysia is largely organised around the idea of preserving the special ethnic status (Malay supremacy) of the Malays as the natives (bumiputera in Malay language, literally means "son of the soil") of the land to equal among the indigenous communities. Although the more dominant Malays, the Orang Asal of East Malaysia and the Orang Asli are considered as bumiputera, they do not enjoy the same equal ranking nor the same rights and privileges.[62] In practice, this has profound implications for the rights of the Orang Asli to the land they have held for a millennia, and which are now largely threatened with transfer to other hands. Prolonged litigation related to these issues is conducted in several states of Peninsular Malaysia, and often ends in favour of the Orang Asli especially those that received public attention.

Economy

_(14779670292).jpg.webp)

Around 1950, most Orang Asli groups followed a traditional way of living, with a subsistence economy supplemented by trade or sales of jungle produce. The main occupation for most groups of Senoi was a primitive form of manual slash-and-burn agriculture.[63] Senoi grows upland rice, cassava, corn, millet, vegetables and a few fruit trees.[64]

Within their customary lands, people cleared a plot of jungle area and used it for agriculture for four to five years, and then moved to another area.[65] The old plots were simply abandoned, and were left to be overgrown with jungle again. The clearing of the new field took from two weeks to a month. The main tools were a peg for planting and a parang. Senoi fields suffered from weeds, pests (rats, birds) and wild animals (deer, elephants). Land management took little time, as did pest control, which was hopeless in the jungle. Therefore, much of the harvest was lost.[66] To protect against wild animals, Senoi fields are usually fenced off. Crops were planted in mid-summer, a small planting was possible in the spring. The goal was to plant varieties of all crops and at least some survived regardless of weather and other conditions. Harvesting took place throughout the year when there was a need for food; only rice yields were determined by a special calendar.

In addition to farming, the Senoi people also engage in other areas such as hunting, fishing and harvesting jungle produce like rattan, rubber, wild banana leaves and so on.[67] Traditionally, blowgun with poison darts were used for Senoi hunting. Blowguns are the subject of great pride for the men.[68] They polish and adorn them, treat them with care and affection; that they would spend more time making the perfect shotgun than building a new house. Hunting objects are relatively small animals such as squirrels, monkeys and wild boars.[69] Hunters returning from hunting are greeted with enthusiasm and dancing.[69] Larger game (deer, wild boar, pythons, binturongs) is obtained with the help of traps, snares, spears.[67] On birds are captured with noose trap on the ground.[67] Fish are caught mainly in special baskets in the form of traps.[67] Poison, dams, fences, spears and hooks are also used.

Within their customary territories, the Senoi people has fruit trees from which seasonal crops are harvested. Bamboo, rattan and pandan are the main raw materials for Senoi handicrafts.[70] Bamboo is indispensable in the construction of houses, household utensils,[71] boats, tools, weapons, fences, baskets, plumbing, rafts, musical instruments and jewelry. The Senoi are masters in basket weaving, especially sophisticated techniques for their production are masters from settled groups. For movement by the rivers usually use bamboo rafts, less often dinghy boats. Production of ceramics, processing of fabrics and metals among the Senoi people is unknown. Traditional fabrics made from the bark of four species of trees are now worn only during special rituals.[72]

The Senoi people also keep chickens, goats, ducks, dogs and cats.[73] However chickens are kept for their own consumption, while goats and ducks are sold to the Malays.[73]

_(14781618475).jpg.webp)

Malay and Chinese traders were supplied with rattan, rubber, wood, fruit (petai, durian) and butterflies in exchange for metal tools (axes, knives), salt, cloth, clothing, tobacco, salt and sugar, or for money.[74]

The general ratio of individual sectors of the economy is unclear, and also differs among different tribes. Many Semaq Beri people are settled farmers, but there are groups among them that have traditionally led a nomadic lifestyle as hunter-gatherers.[75][76] Mah Meri people, who live closer to the coast, are more connected with the sea and are engaged in fishing.[77]

Despite the lack of a formal division of labor between men and women, some differences do exist. The men specialise in hunting and doing laborious work, such as building a house, cutting down large trees, and they also make wind pipes and traps. Women are mainly responsible for childcare and household chores.[78] They are also engaged in collecting, weaving baskets, fishing with baskets. Some work is done by both men and women collectively especially in field work.

Today, most Senoi communities are in constant contact with the larger Malaysian society. Many people live in villages built in the style of a Malay village. As part of the government development campaign, they were given the opportunity to manage of a rubber, oil palm or cocoa plantation.[79] Senoi is also often hired to work in cities as unskilled workforce, but there are also skilled workers, and even professionals. Some groups of Senoi people, including the Jah Hut people; with the support of the government, have learned to make wooden figurines and sell them to tourists. Some groups of Cheq Wong people continue to live in the jungle and mostly follow the traditional way of living. However, their lives have undergone significant changes. They have the opportunity to buy food, soft drinks, cigarettes, new T-shirts or sarongs.

Contacts with strangers for the Senoi people are permeated by distrust,[80] fear and cowardice; a result of centuries of exploitation. The Chinese and Malays buy jungle or agricultural products, but pay much less than the market price. They hire indigenous people, but often do not pay them or pay much less than agreed. At the same time, the quality of public services offered by Orang Asli is much lower than that offered to Malays and Chinese living nearby. Indigenous people are well aware of this and view their relationships with outsiders as deeply unjust and exploitative. However, they rarely complain and prefer to apply their age-old conflict through avoidance practices.

Society

_(14594897940).jpg.webp)

In most Senoi tribes, society is politically and socially egalitarian.[81][82] For the Senoi people, every person is free. People are allowed to do what they like, as long as they do not harm others. The equality of all members of the community was and remains as one of the pillars of Senoi society. Village councils are held from time to time, in which everyone can participate, regardless of age or gender.[83] They usually discuss serious disputes.[83] Collective decisions are made by consensus after open discussions carried out within the community. The deliberation can last for many hours or even days until everyone is satisfied. People are aware that the main purpose of such process is to preserve the unity of the community. If someone is dissatisfied with the community's decision, they are likely to move on to another settlement.

The society is dominated by the elderly. The Senoi people respect the elders and may even elect some of them as elders, but these leaders have no absolute power. The taboo on interfering in individual autonomy does not give the elders any authority to interfere in a person's private life,[82] to prevent him or her from ignoring decisions or leaving. Verbal abilities, not wealth or generosity, are the main prerequisites for leadership.[84] Spiritual wisdom obtained through contact with familiar spirits in dreams are regarded as very important.

Senoi traditions forbid any interpersonal violence, both within their own groups and in relationships with outsiders.[81] This may be due in part to the transformation of society at a time when Orang Asli were victims of Malay slave hunters.[85] The Senoi communities were largely in conflict with various Malay states, which were located downstream. Their survival strategy was to avoid contact with outsiders.[85] A striking example is the modern Cheq Wong people. They strongly emphasize their tribal affiliation, moving at every opportunity as far as possible from the mainstream society.[86][87] The Senoi people prefers to walk away from conflicts,[87] and they are not ashamed to admit that they are afraid.[88] Traditionally, Senoi people adopt passive behaviour towards outsiders to achieve a better result in a difficult situation. Alone, people feel that they are in constant danger. Senoi people tend to be panicked due to their fear of thunderstorms and fear of tigers.[89]

People pass on their fears to their children.[89] This category is considered particularly vulnerable and needs protection. Senoi never punishes or coerces their children, so children's behavior is controlled through taboos. People are especially worried that their children will unknowingly commit a certain violation. Children learn from adult stories about the ubiquitous "evil spirits" that often appear as tigers or other dangerous creatures.[89] Parents can threaten unruly children with thunder if they want to stop inappropriate behaviour. Senoi teaches their children at a very early stage to be afraid of strangers.[90]

With the exception of constant fear, other emotional outbursts are rare among the Senois.[91] They suppress the manifestations of anger, mourning, joy, and even restrain laughter. They do not show emotions in interpersonal relationships. Few open expressions of affection, empathy, or compassion can be seen.[92]

However, interaction with the dominant culture has led to some changes in Senoi society, especially among the southern tribes. The Semelai people[93] and Mah Meri people[94] have long had a hierarchy of political positions and there are also hereditary Batin leaders.

_(14779262964).jpg.webp)

Nuclear families, which own jungle fields; although unstable, are the main form of family in Senoi society.[95] Couples usually slowly and informally move on to a permanent relationship that does not involve any complicated wedding ceremonies.[88] However, in many communities, people have departed from old traditions, they carry out weddings like the Malays, practice dowry for the bride. Family ties in the northern and central Senoi people are concentrated within specific river valleys. Marriages between close relatives are prohibited but marriages among the kinsmen are preferred.[96] In southern indigenous communities, marriages take place within a village or local area, even with cousins. The newlyweds live alternately with the parents of the wife and husband until they have their own housing. Divorce is also common, often even after a long period of time living together.[97] Children and parents decide together where the children will live after their parents divorce, or whichever parent will support the child.[97]

There are differences in the terminology of kinship between different groups of Senoi in terms of linearity and generations. Semai people[98] and Temiar people[99] distinguish between older and younger siblings, but not brothers and sisters. The Semelai people[100] and Mah Meri people[101] distinguish older brothers from older sisters. There are terms in Senoi that correspond to informal age groups, for example, newborns, children, boys and girls, old men and women.

Extended families, which are very closely related and united by a common origin, are amorphous in Senoi society and do not play a significant role in the organisation of the society.[102] An extended family in mountainous areas lives in a common long house.[103]

The local group, usually a village, but sometimes several villages, has collective rights to customary lands (saka).[104] Moving to new sakas, groups often split or merge. Larger tribal groups extend their property to several sakas. There are also large territorial associations occupying land within the main watersheds. Relations between groups and their saka is sentimental, not legal. Neither past British laws nor current Malaysian laws recognise the rights of the Senoi people to their customary lands.

The jungle of the Senoi is owned by the community, but the cleared areas where cultivated plants are grown, as well as the houses belong to individual families. There is also individual ownership of fruit trees in the jungle.[105] After the group moves to a new location, the owners retain the rights to their trees. After a person's death, the land passes to a widow or widower with brothers or children who receive movable property, depending on their needs. Western Semai people divide land or trees obtained after marriage equally between widows and close relatives of the deceased.

Because the jungle and everything in it was the collective property of the community, all jungle produce, except those intended for sale, were brought to the village and shared equally among all present. There is a ban on eating alone (punishable by rule), as food should be shared by all,[106] where individual consumption and accumulation are discouraged.[107] On this basis, there was a practice of immediate consumption of everything that was brought in from the jungle.

Beliefs

_(14594831608).jpg.webp)

Senois follow their own ethnic religion, some are Muslims, there are Christians, Baháʼís. The Senoi do not have a rigid system of religious beliefs and rites.[88] Individual autonomy extends to religious beliefs, creating an unstructured animism, and a developed system of taboos. The Senoi people sees their jungle environment filled with many non-human beings who have consciousness, as well as the people with whom they interact on a daily basis, following a number of rules and prohibitions based on their understanding of the universe. The order in the universe is considered so fragile that people must always be careful not to destroy it, and release bad and hostile horrors into the world.

The world of Senoi is full of evil spirits, which they call mara` meaning, "they that kills (to eat) us".[108] Generally speaking, these includes tigers, bears, elephants and other dangerous animals, as well as supernatural beings. These spiritual creatures cause disease, accidents and other misfortunes. They are unpredictable and malicious, they can always attack for no reason, although certain violations increase the likelihood of such attacks.[108] The only protection against a mara` is another mara` that has become friendly to a person or group of people. This spirit is called gunig (or gunik), a kind of protector or familiar spirit from the spiritual world, which can be summoned to help when troubles occurred.[109] These gunig are believed to be able to help to protect people from aggressive or bad diseases that are usually regarded as spiritual manifestations.[110] There are also good spirits that help at work, in hunting, and in personal life.

The spirits are so timid that most ceremonies are held in the dark of the night.[111] It is believed that the spirits are attracted to aromatic perfumes and beauty, so the ritual areas are decorated with flowers and aromatic leaves.[111] By singing and dancing, people try to reassure the spirits that they are happy. Ceremonies, which usually last two to six nights, are held only to cure illnesses associated with pain or loss of spiritual health of an individual or community as a whole.[111]

Everyone is afraid of thunder, people make a "blood sacrifice" to calm the storm.[112] These victims are individual, not collective.

Humans, most animals and other creatures, according to Senoi beliefs, have several separate "souls".[113] In humans, one soul, the head-soul is localised in the crown of the head on the turf of the hair and the other, heart/blood soul resides in the sternum, with both are able to leave the body when a person is sleeping or in a trance and ultimately death.[114] There are also many other souls such as the eye-soul in the pupil of the eye and the shadow-soul.[89] Therefore, dreams are considered very important, because they establish contact with the supernatural world. They can "warn" about certain events. People believe that they have their own spirits in the afterlife, with whom they communicate in a dream or in a trance. In this way, they can get help in diagnosing and treating diseases caused by evil spirits. Women usually avoid such spiritual connection, because the state of trance is very exhausting for a man; the exception is midwives.[115]

_(14781476535).jpg.webp)

Few people have the ability to deal with supernatural objects. Therefore, they often turn to their shamans from among the villagers for help. Shamans are people who have shown the ability to "communicate" with spirits.[116] It is believed that shamans can be both men and women, and women have the best ability to do so. But such women are few, probably because their bodies are not strong enough to withstand the load of trance.

Shamans also play the role of healers.[117] Sickness and death, according to the Senoi people, are caused by evil spirits, and the actions of spirits, as a result of being provoked by non-compliance with established rules and prohibitions. Mild diseases are treated with herbal medicines,[118] but in serious cases people will seek the shamans. In a trance, the shaman sends his soul to the land of superhuman beings, where he communicates with spirits in order to obtain strong drugs or spells to return the soul of the patient.[119] The souls of the dead, according to the Senoi people, become ghosts. Therefore, the dead are buried on the other side of the river from the village, as it is believed that ghosts cannot cross running water.

With increasing influence from outsiders, Orang Asli have faced competing religious worldviews. Christian missionaries were active in the 1930s, creating the first written texts in Aslian languages.[115] The Malaysian government is pursuing a state policy aimed at Islamising the indigenous population, but such steps are unpopular among the Orang Asli and has created tension among those who refused to convert.[120] The Baháʼí Faith became widespread among the Temiar people. Under the influence of world religions in Senoi communities, there is also the development of innovative syncretic cults, when traditional beliefs are superimposed on certain Malay (Muslim), Chinese (Buddhist) and Hindu elements.[59]

According to JHEOA statistics, among all Orang Asli, animists accounted for 76.99%, Muslims 15.77%, Christians 5.74%, Baháʼís 1.46%, Buddhists 0.03%, and others 0.01%.[22] The number of Muslims among the individual Senoi peoples was as the following:-[22]

| Total population (1996) | Muslim population (1997) | |

|---|---|---|

| Semai people | 26,049 | 1,575 |

| Temiar people | 15,122 | 5,266 |

| Jah Hut people | 3,193 | 180 |

| Cheq Wong people | 403 | 231 |

| Mah Meri people | 2,185 | 165 |

| Semaq Beri people | 2,488 | 956 |

| Semelai people | 4,103 | 220 |

Senoi people accept or reject a particular religion, based on personal and social considerations. By declaring themselves Muslims, they expect state support and certain preferences. On the other hand, in Senoi communities, particularly among the Semai people, there are strong fears that the adoption of a world religion may undermine their identity.

Lifestyle

_(14593516157).jpg.webp)

Traditionally, Senoi people lived in autonomous rural communities,[121] numbering from 30[122] to 300 people.[123] Settlements are usually located on an elevation near the confluence of a stream with a river. The place for settlement is determined by the elder. It should be located away from graves, free from hardwood trees such as Merbau (Intsia bijuga) and so on.[124] The settlement cannot stand in the swamp,[124] it is believed that ghosts "live" in such places. They also avoid places with waterfalls and large rivers, where "mermaids" live.

In low density areas, Senoi communities lived in one place for about three to eight years. When the land has been depleted of its resources, they will move on to a new place. Senoi people rarely leave their native watershed, which forms the customary territory of the community (saka).[125] Few people move more than 20 kilometers from their place of birth during their lifetime. Currently in areas where the population density is higher, especially if Malays and other outsiders have settled there, Senoi communities will settle permanently in a single place and will only return to their jungle fields for harvest time, during which they live in their primitive huts. Communities engaged in the cultivation of wetland rice[126] have also long lived in permanent settlements as many were integrated into modern society.[127]

Traditional houses were built of bamboo, bark and woven palm leaves, covered with dry palm leaves.[128] The buildings stood on stilts at a height of 1 to 3.5 meters above the ground, or even up to 9 meters in areas where there are tigers and elephants.[73]

At the first stage of the settlement's existence, one large long house was built, in which the whole community lived.[129] It was built by the whole community, using hardwoods. Later, nuclear families built separate houses and moved in to live in them. Long houses that have remained in most Senoi settlements, were used for public gatherings and ceremonies.[130] Some communities in remote mountain villages continue to live in long houses that are up to 30 meters long and can accommodate up to 60 people. Nuclear families in such houses have their own separate rooms, in addition, there is a public area.

Most Senoi people now live in Malay style villages built specifically for them by the state government.

.jpg.webp)

Modern Senoi people who come into contact with Malays wear clothing typical of the majority of the Malaysian populations.[131] But in some remote areas, men and women still wear loincloth[131] around their waist in the form of a narrow band of bast fibre. The upper part of the body is rarely covered, sometimes women cover the breasts with another narrow frontal stripe. Typical are tattoos, body painting.[132] The noses are pierced with ornamented porcupine quills, bone, a piece of stick, bamboo sticks[132] or some other decorative objects.[133] Face and body tattoos usually have a magical meaning.[134]

Although the basis of Senoi diet is plant foods,[135] they have a strong thirst for meat.[136] When they say, "I haven't eaten in a few days," it usually means that the person has not eaten meat, fish, or poultry during that time.

Traditional Orang Asli dances are usually used by the shaman as a rite of passage with spirits. Such dances include Gengulang by the Semai people,[137] Gulang Gang by the Mah Meri people, Berjerom by the Jah Hut people, and Sewang by the Semai people and Temiar people.[138]

The only annual ceremony is the post-harvest festival, which is now synchronized with Chinese New Year.[67]

Special rites are associated with the birth of a child. A pregnant woman performs all her usual duties before childbirth. Childbirth takes place in a specially built hut under the supervision of midwives.[139] Immediately after birth, the child receives a name.

The dead are usually buried on the day of death on the other side of the river from where the people live.[140] The grave is dug in the jungle, the body is placed with the head facing towards the west, tobacco, food and personal belongings of the deceased are buried with it.[140] Although the dead are buried with some property, the Senoi people have no concept of the afterlife. Placentas and stillborn babies are buried in trees.[140] Bodies of great shamans are left exposed by placing on a bamboo platform of their house, after which the rest of the villagers will move away from that location.[140] Mourning lasts from one week to a month, during which there are taboos on music, dancing and entertainment.[141] A bonfire is lit at the funeral site for several days. Six days after the burial, the ritual of "closing the grave" is performed and the burial place is "returned to the jungle." In the past, there was a practice among nomadic groups to move a settlement to a new location after the death of one of its inhabitants. That practice has now been abandoned.

Lucid dreaming

_(14594950898).jpg.webp)

In the 1960s, the so-called Senoi Dream Theory became popular in the United States. It is a set of provisions on how people can learn to control their dreams to reduce fear and to increase pleasure, especially sexual pleasure. The Senoi Theory of Dreams refers to the fact that the Senoi allegedly have a theory of dream control and the use of dreams for a specific purpose. After breakfast, people gather and discuss what they dreamed at night, express their thoughts on the meaning of dreams and decide on how to react to it. Open discussion of dreams is especially important to ensure social harmony in society. Conflict situations are also resolved through such a discussion. This practice allegedly makes the Senoi as one of the healthiest and happiest people in the world who has near-perfect mental health.[142]

Kilton Stewart (1902–1965), who had traveled among the Senoi before the Second World War wrote about the Senoi in his 1948 doctoral thesis[143] and his 1954 popular book Pygmies and Dream Giants. His works was publicised by parapsychologist Charles Tart and pedagogue George Leonard in books and at the Esalen Institute retreat center, and in the 1970s Patricia Garfield describes use of dreams among Senoi, based on her contact with some Senoi at the aborigine hospital in Gombak, Malaysia in 1972.[144]

In 1985 G. William Domhoff argued[145][146] that the anthropologists who have worked with the Temiar people report that although they are familiar with the concept of lucid dreaming, it is not of great importance to them, but others have argued that Domhoff's criticism is exaggerated.[147][148] Domhoff does not dispute the evidence that dream control is possible, and that dream-control techniques can be beneficial in specific conditions such as the treatment of nightmares: he cites the work of the psychiatrists Bernard Kraków[149][150] and Isaac Marks[151] in this regard. He does, however, dispute some of the claims of the DreamWorks movement, and also the evidence that dream discussion groups, as opposed to individual motivation and ability, make a significant difference in being able to dream lucidly, and to be able to do so consistently.

See also

Notes

- 1 2 3 2000 and 2003 data do not include persons living outside the settlements and centers designated for Orang Asli

- 1 2 Classified as Proto-Malay but linguistically they are closely related to other Senoic tribes

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 Temoq people are included in the composition of the Semelai people

References

- 1 2 Kirk Endicott (2015). Malaysia's Original People: Past, Present and Future of the Orang Asli. NUS Press. ISBN 978-99-716-9861-4.

- ↑ Ivor Hugh Norman Evans (1968). The Negritos of Malaya. Psychology Press. ISBN 978-07-146-2006-0.

- ↑ Salma Nasution Khoo & Abdur-Razzaq Lubis (2005). Kinta Valley: Pioneering Malaysia's Modern Development. Areca Books. p. 355. ISBN 978-98-342-1130-1.

- ↑ Ooi Keat Gin (2009). Historical Dictionary of Malaysia. Scarecrow Press. ISBN 978-0-8108-6305-7.

- ↑ Fay-Cooper Cole (1945). The peoples of Malaysia (PDF). Princeton, N.J.: D. Van Nostrand Co. p. 92. OCLC 520564.

- 1 2 Sandra Khor Manickam (2015). Taming the Wild: Aborigines and Racial Knowledge in Colonial Malaya. NUS Press. p. 124. ISBN 978-99-716-9832-4.

- ↑ Walter William Skeat & Charles Otto Blagden (1906). Pagan Races of the Malay Peninsula: Preface. Introduction. pt. 1. Race. pt. 2. Manners and customs. Appendix. Place and personal names. Macmillan and Company, Limited. p. 60. OCLC 574352578.

- ↑ The Selangor Journal: Jottings Past and Present, Volume 3. 1895. p. 226.

- 1 2 Tuck-Po Lye (2004). Changing Pathways: Forest Degradation and the Batek of Pahang, Malaysia. Lexington Books. p. 59. ISBN 07-391-0650-3.

- 1 2 Signe Howell (1982). Chewong Myths and Legends. Council of the M.B.R.A.S. p. xiii.

- ↑ Tarmiji Masron, Fujimaki Masami & Norhasimah Ismail (October 2013). "Orang Asli in Peninsular Malaysia: Population, Spatial Distribution and Socio-Economic Condition" (PDF). Journal of Ritsumeikan Social Sciences and Humanities. 6. Retrieved 7 September 2020.

- 1 2 Kirk Endicott (2015). Malaysia's Original People. pp. 1–38.

- 1 2 Ooi Keat Gin (2017). Historical Dictionary of Malaysia. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 403. ISBN 978-15-381-0885-7.

- ↑ Lim Chan-Ing (2004). The Sociocultural Significance of Semaq Beri Food Classification. University of Malaya. p. 49. OCLC 936558789.

- 1 2 Massa: majalah berita mingguan, Issues 425-433. Utusan Melayu (Malaysia) Berhad. 2004. p. 23. OCLC 953534308.

- 1 2 Philip N. Jenner; Laurence C. Thompson; Stanley Starosta, eds. (1976). Austroasiatic Studies, Part 1. University Press of Hawaii. p. 49. ISBN 08-248-0280-2.

- ↑ Debbie Cook (1995). Malaysia, Land of Eternal Summer. Wilmette Publications. p. 125. ISBN 98-399-9080-2.

- 1 2 Geoffrey Benjamin (1976). "Austroasiatic Subgroupings in the Malay Peninsula" (PDF). University of Hawai'i Press: Oceanic Linguistics, Special Publication, No. 13, Part I. pp. 37–128. Retrieved 10 August 2020.

- ↑ Map Archived 18 November 2011 at the Wayback Machine, Keen State College

- ↑ Ivor Hugh Norman Evans (1915). "Notes on the Sakai of the Ulu Sungkai in the Batang Padang District of Perak". Journal of the Federated Malay States Museums. 6: 86.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Nobuta Toshihiro (2009). Living On The Periphery: Development and Islamization Among the Orang Asli in Malaysia (PDF). Center for Orang Asli Concerns, Subang Jaya, Malaysia, 2009. ISBN 978-983-43248-4-1. Retrieved 4 August 2020.

- 1 2 Colin Nicholas (2000). The Orang Asli and the Contest for Resources. Indigenous Politics, Development and Identity in Peninsular Malaysia (PDF). Center for Orang Asli Concerns & International Work Group for Indigenous Affairs. ISBN 87-90730-15-1. Retrieved 27 October 2017.

- 1 2 "Basic Data / Statistics". Center for Orang Asli Concerns (COAC). Retrieved 4 August 2020.

- ↑ Alberto Gomes (2004). Modernity and Malaysia.

- ↑ Selangor Tourism (5 April 2014). "Celebrate Mah Meri's cultural diversity". Sinar Harian. Retrieved 10 November 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 Geoffrey Benjamin (2012). Stuart McGill; Peter K. Austin (eds.). "The Aslian languages of Malaysia and Thailand: an assessment" (PDF). Language Documentation and Description. 11. ISSN 1740-6234.

- ↑ Hamid Mohd Isa (2015). The Last Descendants of The Lanoh Hunter and Gatherers in Malaysia. Penerbit USM. ISBN 978-98-386-1948-6.

- ↑ "Linguistic Circle of Canberra. Publications. Series C: Books, Linguistic Circle of Canberra, Australian National University, Australian National University. Research School of Pacific Studies. Dept. of Linguistics". Pacific Linguistics, Issue 42. Australian National University. 1976. p. 78.

- ↑ Robert Parkin (1991). A Guide to Austroasiatic Speakers and Their Languages. University of Hawaii Press. p. 51. ISBN 08-248-1377-4.

- ↑ Gregory Paul Glasgow & Jeremie Bouchard, ed. (2018). Researching Agency in Language Policy and Planning. Routledge. ISBN 978-04-298-4994-7.

- ↑ Philip N. Jenner; Laurence C. Thompson; Stanley Starosta, eds. (1976). Austroasiatic Studies, Part 1. University Press of Hawaii. p. 49. ISBN 08-248-0280-2.

- ↑ Iskandar Carey & Alexander Timothy Carey (1976). Orang Asli. p. 132.

- ↑ Csilla Dallos (2011). From Equality to Inequality: Social Change Among Newly Sedentary Lanoh Hunter-gatherer Traders of Peninsular Malaysia. University of Toronto Press. p. 262. ISBN 978-14-426-4222-5.

- ↑ Nik Safiah Karim (1981). Bilingualism Among the Orang Asli of Peninsular Malaysia. PPZ. Majalah Malaysiana. OCLC 969695866.

- ↑ Asmah Haji Omar (1992). The Linguistic Scenery in Malaysia. Dewan Bahasa dan Pustaka, Ministry of Education, Malaysia. ISBN 98-362-2403-3.

- ↑ Barbara Watson Andaya & Leonard Y Andaya (2016). A History of Malaysia. Macmillan International Higher Education. p. 14. ISBN 978-11-376-0515-3.

- ↑ Esther Florence Boucher-Yip (2004). "Language Maintenance and Shift in One Semai Community in Peninsular Malaysia" (PDF). University of Leicester. Retrieved 1 October 2020.

- ↑ Philip N. Jenner; Laurence C. Thompson; Stanley Starosta, eds. (1976). Austroasiatic Studies, Part 1. University Press of Hawaii. p. 127. ISBN 08-248-0280-2.

- ↑ "Asyik FM". Retrieved 20 August 2020.

- ↑ Christopher Moseley (2008). Encyclopedia of the World's Endangered Languages. Routledge. ISBN 978-11-357-9640-2.

- 1 2 "Mohd. Razha b. Hj. Abd. Rashid & Wazir-Jahan Begum Karim". Minority Cultures of Peninsular Malaysia: Survivals of Indigenous Heritage. Academy of Social Sciences. 2001. p. 108. ISBN 98-397-0077-4.

- ↑ "Mohd. Razha b. Hj. Abd. Rashid & Wazir-Jahan Begum Karim". Minority Cultures of Peninsular Malaysia: Survivals of Indigenous Heritage. Academy of Social Sciences. 2001. p. 103. ISBN 98-397-0077-4.

- 1 2 Alias Abd Ghani (2015). "The Teaching of Indigenous Orang Asli Language in Peninsula Malaysia". Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences. 208: 253–262. doi:10.1016/j.sbspro.2015.11.201.

- 1 2 "Jelmol – Asli". Discogs. Retrieved 1 October 2020.

- ↑ Rosalam Sarbatly (2021). Hikmah - Unfolding Mysteries of the Universe: Signs, Science, Stories. Partridge Publishing Singapore. ISBN 978-14-828-7903-2.

- ↑ Leonard Y. Andaya (2008). Leaves of the Same Tree: Trade and Ethnicity in the Straits of Melaka. University of Hawaii Press. p. 218. ISBN 978-08-248-3189-9.

- ↑ Christopher R. Duncan, ed. (2008). Civilizing the Margins: Southeast Asian Government Policies for the Development of Minorities. NUS Press. p. 47. ISBN 978-99-716-9418-0.

- 1 2 Helen Leake, ed. (2007). "Jannie Lasimbang". Bridging the Gap: Policies and Practices on Indigenous Peoples' Natural Resource Management in Asia. United Nations Development Programme, Regional Indigenous Peoples' Programme. p. 184. ISBN 978-92-112-6212-4.

- 1 2 Kirk Endicott (2015). Malaysia's Original People. p. 18.

- ↑ Christopher R. Duncan, ed. (2005). Kinta Valley: Pioneering Malaysia's Modern Development. Areca Books. p. 355. ISBN 98-342-1130-9.

- 1 2 3 Govindran Jegatesen (2019). The Aboriginal People of Peninsular Malaysia: From the Forest to the Urban Jungle. Routledge. ISBN 978-04-298-8452-8.

- ↑ "World Directory of Minorities and Indigenous Peoples - Malaysia: Orang Asli". Minority Rights Group International. January 2018. Retrieved 26 August 2020.

- ↑ Roy Davis Linville Jumper & Charles H. Ley (2001). Death Waits in the "dark". p. 40.

- 1 2 3 Yunci Cai (2020). Staging Indigenous Heritage: Instrumentalisation, Brokerage, and Representation in Malaysia. Routledge. ISBN 978-04-296-2076-8.

- ↑ Roy D. L. Jumper (2000). "Malaysia's Senoi Praaq Special Forces". International Journal of Intelligence and CounterIntelligence. 13 (1): 64–93. doi:10.1080/088506000304952. S2CID 154149802. Retrieved 26 August 2020.

- ↑ Chang Yi (24 February 2013). "Small town with many LINKS". The Borneo Post. Retrieved 11 December 2016.

- 1 2 John J. Macionis & Nijole Vaicaitis Benokraitis, ed. (1998). Seeing Ourselves: Classic, Contemporary, and Cross-cultural Readings in Sociology. Prentice Hall. p. 438. ISBN 01-361-0684-6.

- 1 2 3 Geoffrey Benjamin, ed. (2003). Tribal Communities in the Malay World. Flipside Digital Content Company Inc. ISBN 98-145-1741-0.

- ↑ Alberto Gomes (2004). Modernity and Malaysia. p. 60.

- ↑ Robert Harrison Barnes; Andrew Gray; Benedict Kingsbury, eds. (1995). Indigenous Peoples of Asia. Association for Asian Studies. p. 7. ISBN 09-243-0414-6.

- ↑ Towards a People-centered Development in the ASEAN Community: Report of the Fourth ASEAN People's Assembly, Manila, Philippines, 11-13 May 2005. Institute for Strategic and Development Studies. 2005. p. 65. ISBN 97-189-1617-2.

- ↑ Aleksandr Mikhaĭlovich Prokhorov, ed. (1973). Great Soviet Encyclopedia, Volume 23. Macmillan. p. 337. OCLC 495994576.

- ↑ Edward Evan Evans-Pritchard, ed. (1972). Peoples of the Earth: Indonesia, Philippines and Malaysia. Danbury Press. p. 142. OCLC 872678606.

- ↑ M. J. Abadie (2003). Teen Dream Power: Unlock the Meaning of Your Dreams. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 15-947-7571-0.

- ↑ G. William Domhoff (March 2003). "Senoi Dream Theory: Myth, Scientific Method, and the Dreamwork Movement". dreamresearch.net. Retrieved 17 October 2020.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Senoi". Encyclopedia. Retrieved 17 October 2020.

- ↑ Roy Davis Linville Jumper & Charles H. Ley (2001). Death Waits in the "dark". p. 62.

- 1 2 G. William Domhoff (1990). The Mystique of Dreams. p. 16.

- ↑ Muhammad Fuad Abdullah; Azmah Othman; Rohana Jani; Candyrilla Vera Bartholomew (June 2020). "Traditional Knowledge And The Uses Of Natural Resources By The Resettlement Of Indigenous People In Malaysia". JATI: Journal of Southeast Asian Studies. 25 (1): 168–190. doi:10.22452/jati.vol25no1.9. ISSN 1823-4127.

- ↑ Roy Davis Linville Jumper & Charles H. Ley (2001). Death Waits in the "dark". p. 14.

- ↑ Peter Darrell Rider Williams-Hunt (1952). An Introduction to the Malayan Aborigines. Printed at the Government Press. p. 42. OCLC 652106344.

- 1 2 3 Jeffrey Hays (2008). "Semang (Negritos), Senoi, Temiar And Orang Asli Of Malaysia". Facts And Details. Retrieved 17 October 2020.

- ↑ F. L. Dunn (1975). Rain-forest Collectors and Traders: A Study of Resource Utilization in Modern and Ancient Malaya. MBRAS. p. 116. OCLC 1068066195.

- ↑ "Federation Museums Journal, Volumes 16-23". Malaysia Museums Journal. Museums Department, States of Malaya: 80. 1971. ISSN 0126-561X.

- ↑ Philip N. Jenner; Laurence C. Thompson; Stanley Starosta, eds. (1976). Austroasiatic Studies, Part 1. University Press of Hawaii. p. 49. ISBN 08-248-0280-2.

- ↑ Anthony Ratos (2000). Asli: pameran arca kayu daripada koleksi Anthony Ratos: karya orang asli Malaysia daripada masyarakat Jah Hut & Mah Meri. Petronas. p. 23. ISBN 98-397-3812-7.

- ↑ Sharifah Zahhura Syed Abdullah1 & Rozieyati Mohamed Saleh (2019). "Breastfeeding knowledge among indigenous Temiar women: a qualitative study" (PDF). Malaysian Journal of Nutrition. Centre for Research on Women and Gender (KANITA), Universiti Sains Malaysia. 25: 119. doi:10.31246/mjn-2018-0103.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ↑ Colin Nicholas (20 August 2012). "A Brief Introduction: The Orang Asli Of Peninsula Malaysia". Center for Orang Asli Concerns. Retrieved 22 October 2020.

- ↑ Annette Hamilton (June 2006). "Reflections on the 'Disappearing Sakai': A Tribal Minority in Southern Thailand". Journal of Southeast Asian Studies. Cambridge University Press. 37 (2): 293–314. doi:10.1017/S0022463406000567. JSTOR 20072711. S2CID 162984661.

- 1 2 Kirk Endicott (2015). Malaysia's Original People. p. 8.

- 1 2 Jérôme Rousseau (2006). Rethinking Social Evolution: The Perspective from Middle-Range Societies. McGill-Queen's Press - MQUP. p. 96. ISBN 07-735-6018-1.

- 1 2 Sarvananda Bluestone (2002). The World Dream Book: Use the Wisdom of World Cultures to Uncover Your Dream Power. Inner Traditions / Bear & Co. p. 216. ISBN 08-928-1902-2.

- ↑ United Nations (1973). Development of Tribal and Hill Tribe Peoples in the ECAFE Region. UN. p. 54. OCLC 32414686.

- 1 2 Kirk Endicott (2015). Malaysia's Original People. p. 9.

- ↑ Csilla Dallos (2011). From Equality to Inequality: Social Change Among Newly Sedentary Lanoh Hunter-Gatherer Traders of Peninsular Malaysia. University of Toronto Press. ISBN 978-14-426-6171-4.

- 1 2 Salma Nasution Khoo & Abdur-Razzaq Lubis (2005). Kinta Valley: Pioneering Malaysia's Modern Development. Areca Books. p. 352. ISBN 98-342-1130-9.

- 1 2 3 G. William Domhoff (1990). The Mystique of Dreams. p. 17.

- 1 2 3 4 Sue Jennings (2018). Theatre, Ritual and Transformation: The Senoi Temiars. Routledge. ISBN 978-13-177-2547-3.

- ↑ Robert Knox Dentan (1965). Some Senoi Semai Dietary Restrictions. p. 208.

- ↑ Robert Knox Dentan (1965). Some Senoi Semai Dietary Restrictions. p. 188.

- ↑ Paul Heelas (December 1989). "Restoring the justified order: Emotions, Injustice, and the role of culture". Social Justice Research. 3 (4): 375–386. doi:10.1007/BF01048083. S2CID 144865859.

- ↑ "Jawatankuasa Penerbitan". Akademika, Issues 1-9. Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia. 1972. p. 15. ISSN 0126-5008.

- ↑ Suthep Soonthornpasuch, ed. (1986). Contributions to Southeast Asian Ethnography, Issue 5. Double-Six Press. p. 143. OCLC 393434722.

- ↑ Anthony Ratos (2006). Orang Asli and Their Wood Art. Marshall Cavendish Editions. p. 51. ISBN 98-126-1249-1.

- ↑ Edward Westermarck (1922). The History of human marriage, Volume 2. Allerton Book Company. p. 209. OCLC 58208599.

- 1 2 Bela C Maday (1965). Area Handbook for Malaysia and Singapore. U.S. Government Printing Office. p. 170. OCLC 663392103.

- ↑ Timothy C. Phillips (2013). "Linguistic Comparison of Semai Dialects" (PDF). SIL International. p. 50. Retrieved 12 December 2020.

- ↑ Robert J. Parkins (March 1992). "Cognates And Loans Among Aslian Kin Terms" (PDF). Freie Universität Berlin. p. 168. Retrieved 12 December 2020.

- ↑ Paul Bouissac, ed. (2019). The Social Dynamics of Pronominal Systems: A comparative approach. John Benjamins Publishing Company. p. 302. ISBN 978-90-272-6254-7.

- ↑ Nicole Kruspe & Niclas Burenhult (2019). "Pronouns in affinal avoidance registers: evidence from the Aslian languages (Austroasiatic, Malay Peninsula)" (PDF). Centre for Languages and Literature, Lund University, Sweden. p. 19. Retrieved 12 December 2020.

- ↑ Iskandar Carey & Alexander Timothy Carey (1976). Orang Asli. p. 152.

- ↑ F. D. McCarthy (1937). Jungle Dwellers of the Peninsula: The Ple - Temiar Senoi. The Australian Museum Magazine, Volume 8 (1942). p. 61. OCLC 468825196.

- ↑ Hamimah Hamzah (12 October 2009). "Land Acquisition of Aboriginal Land in Malaysia". Slide Share. Retrieved 12 December 2020.

- ↑ National Conference Consumers' Association of Penang (2000). Tanah Air Ku. Consumers' Association of Penang. p. 178. ISBN 98-310-4070-8.

- ↑ Elliott Sober & David Sloan Wilson (1999). Unto Others: The Evolution and Psychology of Unselfish Behavior. Harvard University Press. p. 177. ISBN 06-749-3047-9.

- ↑ Signe Lise Howell (1981). Chewong Modes Of Thought (PhD thesis). University of Oxford. pp. 99–100. S2CID 145523060. Retrieved 12 December 2020.

- 1 2 Clayton A. Robarchek (1979). "Learning to Fear: A Case Study of Emotional Conditioning". American Ethnologist. 6 (3): 561. doi:10.1525/ae.1979.6.3.02a00090.

- ↑ J. Gackenbach & S. LaBarge, ed. (2012). Conscious Mind, Sleeping Brain: Perspectives on Lucid Dreaming. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 49. ISBN 978-14-7570-423-5.

- ↑ Yogeswaran Subramaniam & Juli Edo (2016). "Common Law Customary Land Rights" (PDF). Shaman: Journal of the International Society for Academic Research on Shamanism: 138–139. Retrieved 21 December 2020.

- 1 2 3 Linda A. Bennett (1993). David Levinson (ed.). Encyclopedia of World Cultures, Volume 3. G. K. Hall. p. 238. ISBN 08-168-8840-X.

- ↑ Peter Darrell Rider Williams-Hunt (1983). An Introduction to the Malayan Aborigines. AMS Press. p. 75. ISBN 04-041-6881-7.

- ↑ Institute for Medical Research (Malaysia) (1951). The Institute for Medical Research, 1900-1950. Printed at the Government Press. p. 10. OCLC 3533361.

- ↑ Michael Berman (2009). Soul Loss and the Shamanic Story. Cambridge Scholars Publishing. p. 22. ISBN 978-14-438-0815-6.

- 1 2 David Levinson & Johannes Wilbert, ed. (1993). Encyclopedia of World Cultures: South America / Johannes Wilbert, volume editor. Vol. 7, Volume 2. G.K. Hall. p. 238. ISBN 08-168-8840-X.

- ↑ Geoffrey Samuel & Samuel Geoffrey (1990). Mind, Body and Culture: Anthropology and the Biological Interface. Cambridge University Press. p. 114. ISBN 05-213-7411-1.

- ↑ Grange Books PLC (1998). The World of the Paranormal: A Unique Insight Into the Unexplained. Grange Books. p. 203. ISBN 18-562-7720-8.

- ↑ Steven Foster (2009). "Balancing Nature and Wellness --Malaysian Traditions of "Ramuan" The History, Culture, Biodiversity and Scientific Assimilation of Medicinal Plants in Malaysia". HerbalGram: The Journal of the American Botanical Council (84). Retrieved 1 January 2021.

- ↑ Paul C.Y.Chen (1967). "Medical systems in Malaysia: Cultural bases and differential use". Social Science & Medicine. 9 (3): 171–180. doi:10.1016/0037-7856(75)90054-2. PMID 1129610.

- ↑ Victoria R. Williams (2020). Indigenous Peoples: An Encyclopedia of Culture, History, and Threats to Survival. ABC-CLIO. p. 844. ISBN 978-14-408-6118-5.

- ↑ Alan G. Fix (2012). The Demography of the Semai Senoi. University of Michigan Press. p. 11. ISBN 978-09-322-0660-2.

- ↑ Howard Rheingold (2012). Excursions to the Far Side of the Mind: A Book of Memes. Stillpoint Digital Press. ISBN 978-19-388-0801-2.

- ↑ Geok Lin Khor & Zalilah Mohd Shariff (2019). "Do not neglect the indigenous peoples when reporting health and nutrition issues of the socio-economically disadvantaged populations in Malaysia". BMC Public Health. 19 (1): 1685. doi:10.1186/s12889-019-8055-8. PMC 6916214. PMID 31842826.

- 1 2 Nor Azmi Baharom & Pakhriazad Hassan Zak (2020). "Socioeconomic Temiar community in RPS Kemar, Hulu Perak". IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science. 596 (1): 012072. Bibcode:2020E&ES..596a2072A. doi:10.1088/1755-1315/596/1/012072.

- ↑ Hamimah Hamzah (2013). "The Orang Asli Customary Land: Issues and Challenges" (PDF). Journal of Administrative Science. 10 (1).

- ↑ Journal of Malaysian Studies, Volumes 1-2. Universiti Sains Malaysia. 1983. p. 82.

- ↑ Peter Turner; Chris Taylor; Hugh Finlay (1996). Malaysia, Singapore & Brunei: A Lonely Planet Travel Survival Kit. Lonely Planet Publications. p. 36. ISBN 08-644-2393-4.

- ↑ F. L. Dunn (1975). Rain-forest Collectors and Traders: A Study of Resource Utilization in Modern and Ancient Malaya. MBRAS. p. 62. OCLC 1068066195.

- ↑ Hasbollah Bin Mat Saad (2020). A Brief History Of Malaysia: Texts And Materials. Pena Hijrah Resources. p. 159. ISBN 978-96-755-2315-1.

- ↑ Richard Corriere (1980). Dreaming & Waking: The Functional Approach to Dreams. Peace Press. p. 103. ISBN 09-152-3841-1.