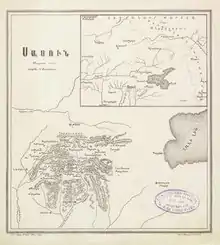

Sasun or Sassoun (Armenian: Սասուն), also known as Sanasun or Sanasunkʻ (Armenian: Սանասունք), was a region of historical Armenia. The region is now divided among the modern Turkish provinces of Muş, Bingöl, Bitlis, Siirt, Batman, and Diyarbakır, with the modern-day district of Sason in Batman Province encompassing only one part of historical Sasun.[1]

In antiquity, Sasun was one of the ten districts (gawaṛ) of the province of Aghdznikʻ (Arzanene) of the Kingdom of Armenia. Over time, Sasun came to denote a larger region than the original gawaṛ. In the 10th century, an independent Armenian principality based in Sasun and ruled by a branch of the Mamikonian dynasty emerged and existed until the 12th century. The region was conquered by the Ottoman Empire in the 16th century, and the district (kaza) of Sasun was made a part of different administrative divisions before finally being attached to the Mush sanjak of the Bitlis vilayet. Kurds settled in Sasun as early as the end of the 13th century, and an autonomous Kurdish emirate existed there until the 19th century.

The inhabitants of Sasun frequently enjoyed an autonomous or semi-independent status up to the modern era owing to the region's remoteness and inaccessibility, as well as to the armed resistance of its inhabitants. Sasun holds a significant place in Armenian culture, history and historical memory. The Sasun Armenians' reputation for courage and resistance to foreign rule is reflected in the Armenian national epic Daredevils of Sasun. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, Sasun became a focal point of the Armenian fedayi movement and was the site of numerous clashes between Armenian militiamen, Kurdish irregulars and the Ottoman authorities. The Armenians of Sasun showed armed resistance during the Armenian genocide in 1915, during which most of them were killed. Some Armenians from Sasun managed to flee and settled in the territory of modern-day Armenia, while a small number remained in Sasun. Most of the Armenians that remained in Sasun after the genocide have since left the region, settling primarily in Istanbul, and the region is now populated primarily by Kurds.

Name

The exact etymology of Sasun is unknown, although various folk etymologies exist.[2] The name is first definitely attested in the 7th-century Armenian geography Ashkharhatsʻoytsʻ, attributed to Anania Shirakatsi. Sanasun is the older form of the name, and both versions are also attested in the plural forms Sanasunkʻ and Sasunkʻ.[3][lower-alpha 1] The Greeks referred to the region in the plural, as Sanasounitai (Σανασουνῖται), which is likely a direct translation of Sanasunkʻ and also refers to the inhabitants of Sanasun.[5] In the Armenian tradition, the name of Sasun is traditionally associated with Sanasar (i.e., biblical Sharezer), the son of the Assyrian king Sennacherib who fled to Armenia after murdering his father․[6][7] Sanasar is said to have settled in the area around Mount Sim, which was called Sanasunkʻ (as if meaning "Sanasar's progeny") after him and his descendants that populated the region.[6][7] The prominent Armenian noble house of Artsruni and the bdeashkhs of Tsopʻkʻ and Aghdznikʻ, the latter of which ruled over Sanasun until the fifth century, all claimed descent from Sanasar.[6] It has been proposed that the placename is related to the town or fortress of Sassu mentioned in the cuneiform inscriptions of the Assyrian king Tiglath-Pileser III (8th century BCE).[2] Nicholas Adontz connects Sasun/Sanasun with Ususuani, one of the conquered lands mentioned in the inscriptions of the Urartian king Menua (9th-8th century BCE).[8]

Geography

Located in the eastern Taurus Mountains, Sasun was one of the most mountainous and inaccessible regions of historical Armenia, characterized by precipitous gorges and canyons, grassy valleys, thick forests, and river rapids.[1][9] Its two main mountain ranges were the Sim Mountains (also known as Kurtik or Simsar) to the north, which separated Sasun from the plain of Mush, and the Sasun Mountains to the east, whose most prominent peaks are Andok (Antok), Tsovasar (Zowasor), Kepin and Maratʻuk (Marutʻasar).[10][lower-alpha 2] The source of the Batman River (Kʻaghirtʻ in the old Armenian sources), a tributary of the Tigris, was located in Sasun.[9][10] The altitude in Sasun dropped drastically going from north to south, going from 7,000 feet (2,100 m) in the north to 2,400 feet (730 m) in the south along a distance of just 100 miles (160 km).[1] Summers were temperate in the north and very hot in the south, while winters were severe and long everywhere.[1] The main roads leading out of Sasun, which went through mountain passes to the north, were made impassable by snowfall throughout the winter, cutting the region off from the outside world.[1] The area was also frequently stricken by earthquakes.[11] Sasun received very little rainfall and had poor soil for agriculture, so the population was largely dependent on their herds (mainly sheep) for survival․[11] Agriculture and some grape cultivation occurred on a limited scale.[10][11] Although Sasun was replete with timber and deposits of iron and copper, these remained largely unexploited (except for limited local use) due to the lack of transportation infrastructure for export.[11]

Within the Kingdom of Armenia, Sanasun or Sasun bordered the districts of Hashteankʻ of Tsopʻkʻ province to the northwest, Tarōn, Aspakuneatsʻ Dzor and Khoytʻ (Khutʻ) of Turuberan province to the northeast, and Salnoy Dzor, Gzekh, Aghdzn, and Npʻrkert of Aghdznik province to the east and southeast.[9] Suren Yeremian estimates the area of historical Sanasun at 2,400 km2 (930 sq mi).[12] In later periods, Sasun referred to a broader geographical, economic and political region which included historical Sanasun and the adjacent territories, and was considered a part of the region of Taron-Turuberan.[10][13] By one definition, Sasun encompassed the area between the Haçres and Sim/Kurtik Mountains in the north to Sasun village (modern Derince, Sason) in the south and between Kulp in the west and Kavakbaşı (historical Khoytʻ) in the east.[1] After the creation of the Bitlis vilayet in 1875, most of Sasun was made part of the sanjak of Mush of the Bitlis vilayet and called the kaza of Sasun, with other parts of the greater region of Sasun falling under adjacent sanjaks.[14][lower-alpha 3] Little is known for certain about Sasun's internal sub-divisions during the late Ottoman period, and these seem to have changed frequently.[16] One source gives the names of the sub-districts (or nahiye) of Sasun in the late 18th and early 19th centuries as Brnashēn, Bun Sasun ("Sasun proper"), Kharzan, Khutʻ-Brnashēn, Khulpʻ, Hazzo-Khabljoz, Motkan, Shatakh, Talvorik (Talori), and Pʻsankʻ․[16]

History

Early history

Sasun or Sanasun formed a part of the territory of the Kingdom of Urartu, as well as the Kingdom of Armenia under the successive rule of the Orontid, Artaxiad and Arsacid dynasties.[10] Sanasun was a territory of the bdeashkh (vitaxa, viceroy) of Aghdznikʻ, an office that was likely constituted during the reign of Tigranes the Great (1st century BCE) and continued to exist until the mid-5th century.[17] It has been suggested that Sanasun formed "a tribal territory under its own chieftains" rather than a holding of the bdeashkh, but there is little evidence to support this.[4] Although the early Armenian historian Movses Khorenatsi does not mention Sanasun by name, he refers to "the Taurus Mountain, that is Sim and all the and all the Kłesurkʻ [Kleisourai, mountain passes]," which is clearly describing the territory of Sanasun, as part of the territories granted to Sharashan, bdeashkh of Aghdznikʻ.[4] Sanasun was strategically important because of its geographical position; the river valleys that it encompassed, though difficult to pass, were a logical invasion route from the south toward the plain of Mush.[4] The chief fortress of Sanasun bore the same name and was located near the later village of Sasun (modern Derince).[18][lower-alpha 4] Sanasun presumably came under direct Roman suzerainty together with the entire bdeashkhutʻiwn (viceroyalty) of Aghdznikʻ as a result of the Peace of Nisibis in 298 CE, although the viceroyalty may have remained under the de facto authority of the King of Armenia.[20][21] The Romans gave up rights to Aghdznikʻ to Sasanian Iran in 363 and the viceroyalty was possibly reconquered by Armenia in the 370s.[20] Aghdznikʻ was divided between the Roman and Sasanian empires in the partition of Armenia in 387, with most of it going it to the Sasanians.[20] After the partition of Armenia, a line of mountain fortifications were built in Sasun, which had become the southern frontier of central Armenia.[22]

Sasun maintained its independence or semi-independence after the dethroning of the last Arsacid king of Armenia in 428.[10] In the 510s, the future marzban of Armenia Mzhezh Gnuni led the Armenians of Sasun to defeat a group of raiding Huns.[10] At some point after the Arab conquest of Armenia, Sasun came under the control of Mamikonian dynasty and a became a key stronghold for resistance against Arab rule.[23] Starting from the end of the 8th century, Sasun was ruled by the Tornikians, a branch of the Mamikonian family.[24] In 851, the population of Sasun, under the leadership of a certain Hovhan Khutetsi, defeated an Arab army on the plain of Mush and killed its commander Yusuf.[24] In 852 the Abbasid commander Bugha al-Kabir attacked Sasun and massacred thousands of its inhabitants.[24] Despite this, the Tornikians maintained their control over Sasun and continued to resist Arab rule.[24] The frequent revolts of the Armenians of Sasun against Arab rule served as the historical basis for the medieval Armenian epic Daredevils of Sasun.[24]

Principality of Sasun

Continuing the long-standing rivalry between the Mamikonian and Bagratuni dynasties and encouraged by the Byzantine Empire, the Tornikians of Sasun conquered a part of the Bagratunis' holdings in Tarōn in the early 10th century.[24] Soon after, however, the Tornikians accepted the suzerainty of the Bagratuni kingdom of Armenia based in Ani.[24] At some point during the rule of the Tornikians, an episcopal see was established at Sasun with its seat at the monastery of Surb Aghberik or Vandir.[25] Tarōn was conquered in its entirety by the Byzantines in the last decade of the 10th century, but the Tornikian principality of Sasun managed to maintain its independence from Byzantium and the Seljuks.[24] In the 11th century Sasun was ruled first by Mushegh Tornikian, then by his son Tornik, who again expanded the principality of Sasun into Tarōn and conquered the city Arsamosata and parts of Andzit.[24] Arab sources refer to the ruler of Sasun as malik al-Sanasina.[24] In 1059, Tornik beat back a Seljuk incursion into Tarōn.[24] In 1073, he defeated the Byzantine-Armenian general-turned-ruler Philaretos Brachamios, who attempted to subject Sasun to his rule.[24] That same year, Tornik was assassinated through the conspiring of Philaretos and the emir of Mayyafariqin.[26]

He was succeeded by his son Chordvanel (1073–1120s), who is said to have captured thirty villages from the emirate of Arzen.[24] Under Chordvanel's son Vigen (1120s–1175), the principality expanded further westward and established alliances by marriage with the Artsrunis of Moks, the Katakalons, and the Pahlavunis.[24] Vigen was succeeded by his grandson, Shahnshah (1175–1188), who unsuccessfully attempted to make his brother Catholicos at Rumkale.[24][lower-alpha 5] Catholicos Gregory IV called on Shah-Armen Beytemür, ruler of Ahlat, for aid against Shahnshah's aggression, but Beytemür was taken prisoner and ransomed in exchange for a certain fortress called Tʻardzean.[24] However, Beytemür then renewed his attack on Sasun, defeated Shahnshah and imposed a heavy tribute.[24] In 1188, Shahnshah and his brothers Vasil and Tornik fled to the Armenian kingdom of Cilicia after being dispossessed by the Shah-Armens.[24][28] King Leo II of Cilicia granted them the fortress of Seleucia.[24] Some branches of the Tornikians remained in Sasun, taking refuge in the more inaccessible parts of the region.[24]

13th century to Ottoman rule

Under Mongol rule, Sasun was administered together with the rest of southwestern Armenia and maintained its autonomous status.[24] Hulagu Khan conquered Sasun in the 1260s and annexed it to the Ilkhanate.[24] According to the Armenian historian Kirakos Gandzaketsi, Hulagu delegated the administration of Sasun to a member of the Artsruni family named Sadun.[24] During Timur's campaign in Armenia in 1387, the population of Tarōn was saved from destruction by taking refuge in the mountains of Sasun.[24] In the 15th century, Sasun first fell under the suzerainty of the Qara Qoyunlu, then under that of the Aq Qoyunlu.[24] In the 16th century Sasun was conquered by the Ottoman Empire.[24] Kurdish presence in Sasun can be traced to the end of the 13th century;[29] Kurds settled in Sasun in greater numbers after the Ottoman conquest.[24][30] According to the correspondence between Joseph Emin, an early Armenian revolutionary, and Hovhan Mshetsi, the abbot of St. Karapet Monastery in Mush, Sasun had its own armed detachments and cavalry in the second half of the 18th century.[24] In first quarter of the 19th century and as late as the 1880s, Sasun was effectively governed by its own laws and was ruled by an Armenian prince (ishkhan) elected by a council of elders (avagani).[24][31] Sasun's Armenians bore arms, which was forbidden under Ottoman law, produced their own weapons, and relied on nothing from the outside world.[24][32] Ottoman tax collectors could not effectively work in Sasun due to its remoteness, and until 1890 Sasun Armenians paid their taxes once a year as a lump sum.[31] There were also illegal taxes imposed by Kurdish chieftains on the Armenians, which were frequently cause for conflict.[31] Armenian sources write that relations between the Kurds and Armenians of Sasun worsened due to the deliberate policy of the Ottoman authorities.[24][30]

In the late 19th century, Sasun was made a part of the Bitlis vilayet, with most of it falling under the Sasun kaza in the sanjak of Mush and smaller sections going to the sanjaks of Genç and Siirt.[33] In the 1880s, clashes occurred in Sasun between Armenian militiamen and Ottoman gendarmes.[33] The Sasun Armenians were led by Vardan Goloshian, an Armenian revolutionary from Tiflis.[33] The escalation of Armenian-Kurdish violence in Sasun in the early 1890s and the Ottoman intervention that culminated in the 1894 Sasun rebellion and massacre has been explained variously. Many sources view these events as a result of deliberate provocations by the Ottoman authorities, who sought to bring Sasun to heel as a potential hotbed for rebellion.[24][30][34] In 1891–92, the hamidiye irregular cavalry units were sent by the Ottoman authorities to attack Sasun, but were fought off by Armenian forces.[33] The famous Armenian fedayi Arabo came to prominence in these battles.[33] Several Armenian revolutionaries traveled to Sasun to join in the armed resistance. Among the leaders of the Armenian militias were Mihran Damadian, Hampartsoum Boyadjian, Hrayr Dzhoghk, Aghbiur Serob, Kevork Chavush and Krko (Krikor Moseyan).[33] Unable to bring Sasun to submission with police forces and Kurdish irregulars in 1893, the Ottoman authorities sent the regular army to surround Sasun and declared martial law in the area.[33] The Ottoman Fourth Army under the command of Zeki Pasha was charged with pacifying Sasun.[33] After several months of fighting, the outnumbered Armenian forces under the leadership of Hampartsoum Boyadjian were defeated and the inhabitants of a number of villages in Sasun were massacred.[33] The rebellion and massacre at Sasun is regarded as the beginning of the Hamidian massacres and provoked an international outcry.[35]

Armenian fedayi activity resumed in Sasun in 1896 under the leadership of Andranik, Aghbiur Serob and Spaghanats Makar.[33] Sasun was attacked by the Ottoman Army and Kurdish irregulars again in 1904. The Armenian defenders were led by Hrayr Dzhdoghk, Andranik, Kevork Chavush, Sebastatsi Murad, Spaghanats Makar, Mshetsi Smbat, Sheniktsi Manuk, and Kaytsak Vagharshak, among others.[33] Although the Armenian militiamen were defeated and the region's population again subjected to massacre, the population of Sasun rejected the Ottoman authorities' demand to resettle on the plain of Mush.[33]

In the years prior to the Armenian genocide, a number of Sasun Armenians migrated to Aleppo (modern-day Syria), which already had a sizable Armenian community.[36] The majority of the Sasun Armenians in Aleppo made their living there as bakers or millers.[37] A Compatriotic Union of Sasun was later formed in Aleppo.[38]

Armenian genocide

In 1915, at the onset of the Armenian genocide, Armenian leaders in Mush and Sasun debated over strategy, with some advising caution and others calling for a preemptive uprising to take control of Sasun and the plain of Mush until the arrival of the Russian army.[39] The main partisan leaders were Hagop Godoyan, Misak Bdeyan and Goryun, while the chief political leaders were Ruben Ter Minasian and Vahan Papazian (Goms) of the Armenian Revolutionary Federation.[39] Ultimately, Ter Minasian and Papazian's strategy of cautiously preparing for defense in the mountains of Sasun was followed.[40]

In May 1915, the Ottoman army unsuccessfully attacked Sasun with the help of Kurdish tribes.[41] Armenian partisan units remained in Sasun in June–July 1915 while Ottoman forces crushed Armenian resistance in Mush and massacred the survivors.[42] After eradicating the Armenians on the plain of Mush, the Ottoman forces focused their efforts on attacking Sasun.[43] The district was surrounded and subjected to heavy bombardment.[43][40] Ruben Ter Minasian estimates that around 30,000 Ottoman troops and Kurdish irregulars surrounded Sasun.[43] On the Armenian side, some 1,000 men armed mainly with hunting rifles defended the kaza of Sasun, where about 20,000 natives and 30,000 refugees from other regions were under siege.[43] Suffering from starvation and shortages in ammunition, on August 2, 1915 the defenders attempted to break out of the encirclement together with the besieged population, but only a few thousand managed to escape and reach Russian-controlled territory (at the time, the frontline ran through Malazgirt, about 25 miles from Mush).[43] The vast majority of the population, including tens of thousands of refugees from nearby areas, was massacred.[44] A few thousand were deported, while a few hundred were taken into Kurdish families or seized as war booty by Turkish officers.[45] Others hid in mountains and canyons and crossed over to Russian-controlled territory in March 1916, when the Russian army captured Mush.[46] Those Armenians from Sasun who managed to reach Eastern Armenia (the territory of modern-day Armenia) settled mainly in villages around Talin and Ashtarak.[33]

An unknown number of Sasun Armenians survived the genocide by converting to Islam. Many of these Armenian converts later moved to different parts of Turkey.[47][48] Some Sasun Armenians preserved their Christian faith and managed to remain in Sasun after the genocide, although many of these later converted to Islam from the 1960s onward.[49] According to one estimate, one third of the Armenian community in Istanbul is made up of Armenians from Sasun.[47]

Population

Figures for the population and number of settlements in Sasun from the late Ottoman period differ significantly. This can be attributed to the difficulty of collecting data in such a remote area, as well as the reluctance of the inhabitants to provide information to officials and, later, displacement and death associated with local violence and massacres.[11][50] Additionally, Armenian populations were frequently undercounted by the authorities after 1878 to downplay Armenian presence in the empire's eastern provinces.[51] According to Justin McCarthy, comparatively accurate data was collected in 1911, which, when adjusted for the undercount of women and children typical of Ottoman census data, shows a population of 9,827 Muslims and 8,576 Armenians in the kaza of Sasun (18,403 people total), 20,108 Muslims and 4,711 Armenians in the kaza of Kulp (24,819 total), and 39,887 Muslims and 47,879 Armenians (87,766 total) in the kaza of Mush.[52] Raymond Kévorkian gives the Armenian population of the kaza of Sasun on the eve of the First World War as 24,233, based on the census carried out by the Armenian Patriarchate of Constantinople.[53] For the greater region of Sasun, Kévorkian counts 80,233 Armenians at the start of the Armenian genocide.[45] Armenian families in Sasun were large, with couples having eight children on average.[54]

The two main ethnic groups in Sasun were Armenians and Kurds. Ethnographer and Sasun native Vardan Petoyan writes that a very small number of Yazidis and Assyrians also lived in Sasun.[55] According to scholar Tigran Martirosyan, "the Armenians of Sassoun held a relative demographic preponderance or a significant numerical strength in most areas within the region up until the Genocide in 1915."[15] Sasun was likely divided into smaller administrative units with the intention of reducing the relative percentage of Armenians in each unit.[15]

Armenians

In accordance with the legend of Sanasar, son of Sennacherib, settling in Sanasun, the 9th-10th-century Armenian historian Tovma Artsruni writes that the people of Sasun "are the peasants of Syria who followed [to Armenia] Adramelēkʻ and Sanasar."[56] The Armenologist Heinrich Hübschmann was of the opinion that the inhabitants of Sasun were historically not Armenians, spoke a different language, and were clearly distinguishable from Armenians as late as the 10th century, citing Tovma Artsruni's descriptions of their way of life and language as evidence.[57] Specifically, Tovma Artsruni notes the "obscure and inscrutable speech" of the inhabitants of Sasun and states that "Half of them lose their native tongue from living so far apart and never greeting each other, and their mutual speech is a patchwork of borrowed words. They are so profoundly ignorant of each other that they even need interpreters."[58] Armenian authors interpret this as referring to various and complex dialects of Armenian spoken by the Armenians of Sasun at the time.[10][57]

The reputation of the Armenians of Sasun was one of a hardy, courageous and stubborn group of mountaineers.[59] Tovma Artsruni describes them as "savage in their habits, drinkers of blood, who regard as naught the killing of their own brothers and even of themselves" but adds that they are "hospitable and respectful to strangers."[56] The early 20th-century Armenian historian A-Do (Hovhannes Ter-Martirosian) describes Sasun Armenians as "rough, proud, individualist and brave, but poor."[60] The Sasun Armenians' bravery and propensity for resistance to oppression is depicted in the Armenian epic poem Daredevils of Sasun, which narrates the story of four generations of heroes from Sasun who fight against the Arab conquerors during the time of Arab rule in Armenia.[32] The epic was inspired by the memory of Sasun's protracted struggle against the Arabs and other foreign conquerors.[24]

The Armenians of Sasun spoke their own dialect of Western Armenian, which is included in the Mush-Tigranakert (Diyarbakır) or south-central group of Armenian dialects. The Sasun dialect itself was divided into two main sub-dialects: Hazro and Geliyeguzan.[61]

Kurds

In the late Ottoman period, Kurds in the Sasun region were either sedentary villagers or seminomads who moved between two main pastures seasonally but had home villages.[62] The Kurdish settlements formed a rough circle around the central area of Armenian settlement in Sasun.[63] Kurds in Sasun strongly identified with their respective tribes and sub-tribes and were not unified as a single group.[64] The main Kurdish tribes in Sasun, which each had their own sub-tribes (kabile), were the Bekranlı (also known as the Bikran), the Badıkanlı, the Sasunlu, and the Hıyanlı.[65] Relations between these tribes were often tense, which sometimes led to armed clashes.[65] Some sources also speak of a group of non-Muslim Kurds called the Baliki or Belekʻtsʻi, who lived in the foothills of Mount Maratʻuk, spoke the Sasun dialect of Armenian, visited the Armenian holy sites, and cooperated with the Armenians in times of rebellion.[24][66][55] In 1894, the Armenian villages of Sasun were mostly allied with and dependent on the Sasunlu Kurds, to whom they paid tribute.[65] The main villages of the semi-nomadic Bekranlı were to the southwest of Sasun. They had lost their authority over some villages in Sasun to the Armenians and the Sasunlu some time before the 1890s.[67]

Notable natives

- Arabo (Arakel Mkhitarian, 1863–1893), Armenian fedayi leader, born in Kurtʻeṛ in Sasun

- Hrayr Dzhoghk (Armenak Ghazarian, 1864–1904), Armenian fedayi leader, born in Aharonkʻ in Sasun (now Karlık, Kulp)

- Kevork Chavush (1870–1907), Armenian fedayi leader, born in Mktʻenkʻ in Sasun (now Topluca, Sason)

- Khachik Dashtents (1910–1974), Soviet Armenian author, born in Dashtadem in Sasun (now Çukurca, Mutki)

- Vardan Petoyan (1892–1965), Soviet Armenian ethnographer and educator, born in Geliyeguzan in Sasun (now Cevizlidere, Muş)

- Garo Sassouni (1889–1977), an Armenian intellectual, author, journalist, revolutionary, educator, and public figure, born in Aharonkʻ in Sasun (now Karlık, Kulp)

Notes

- ↑ As is common for Armenian district names, many of which are found only in the plural.[4]

- ↑ The highest peak (2685 m) of the Sim Mountains is also called Sim, Simsar or Kurtik. Maratʻuk is the highest peak of the Sasun Mountains at 2967 m.

- ↑ Bun Sasun, Shatakh, and Hazzo-Khabljoz were transferred to Mush sanjak; Khutʻ-Brnashēn and Motkan to Bitlis sanjak (a sanjak of the same name as the vilayet); Khian, Khulpʻ, and Talvorik to Genç; and Pʻsankʻ and Kharzan to Siirt.[15]

- ↑ In later periods, the fortress was also called Sasuni Berd, Davtʻaberd, Davtʻi Berd, Sasuntsʻi Davtʻi Berd (i.e. "the fortress of David of Sasun"), and Kʻaghkik.[19]

- ↑ V. Petoyan writes that Vigen was succeeded by his son Chordvanel II, who died at a young age and was then succeeded by Shahnshah.[27]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 McCarthy, Turan & Taşkıran 2014, p. 3.

- 1 2 Hakobyan, Melikʻ-Bakhshyan & Barseghyan 1998, p. 506a.

- ↑ Hiwbshman 1907, p. 173.

- 1 2 3 4 Hewsen 1992, p. 160.

- ↑ Hewsen 1992, pp. 160, 162.

- 1 2 3 Hiwbshman 1907, pp. 174–175.

- 1 2 Tomashēk 1896, pp. 5–6.

- ↑ Adontsʻ 1972, pp. 198–199.

- 1 2 3 Hakobyan, Melikʻ-Bakhshyan & Barseghyan 1998, p. 505b.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Danielyan 1984, p. 199.

- 1 2 3 4 5 McCarthy, Turan & Taşkıran 2014, p. 6.

- ↑ Eremyan 1963, p. 79.

- ↑ Petoyan 1965, p. 3.

- ↑ Hovannisian 2001, p. 3.

- 1 2 3 Martirosyan 2020, p. 60.

- 1 2 Hakobyan, Melikʻ-Bakhshyan & Barseghyan 1998, p. 505c.

- ↑ Hewsen 1992, pp. 158–160.

- ↑ Hewsen 1992, p. 162.

- ↑ Hakobyan, Melikʻ-Bakhshyan & Barseghyan 1998, p. 506b.

- 1 2 3 Hewsen 1992, p. 158.

- ↑ Toumanoff 1961, p. 30.

- ↑ Hewsen 1992, p. 48: "After the loss of the principality of Aghdznik to the Persians in 387, however, Taron became a frontier province, and thereafter a line of defensive positions was constructed in the part of the Taurus Mountains known as Sasun which not only bordered Taron but now formed the frontier of all of central Armenia on the south".

- ↑ Danielyan 1984, pp. 199–200.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 Danielyan 1984, p. 200.

- ↑ Hewsen 2001, pp. 48, 51.

- ↑ Petoyan 1955, p. 86.

- ↑ Petoyan 1955, pp. 88–89.

- ↑ Hewsen 1992, p. 164.

- ↑ Haroutyunian 1997, p. 88: "But the Kurds can not be traced in Sasun until the end of the XIII century. Probably, the Kurds appeared in Sasun at the end of the XIII century, because then there is some mention about their presence in the Sasun mountains (Abeghian, pp. 362, 371), which are gradually conquered by them".

- 1 2 3 Badalyan 1996, p. 401.

- 1 2 3 Martirosyan 2020, p. 62.

- 1 2 Martirosyan 2020, p. 63.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 Danielyan 1984, p. 201.

- ↑ Miller 2018, p. 19.

- ↑ Poghosyan 1996a, p. 402.

- ↑ Shemmassian 2001, p. 178.

- ↑ Shemmassian 2001, p. 182.

- ↑ Shemmassian 2001, p. 189, n48.

- 1 2 Walker 2001, p. 199.

- 1 2 Walker 2001, p. 202.

- ↑ Kévorkian 2011, p. 345.

- ↑ Walker 2001, p. 203.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Kévorkian 2011, p. 352.

- ↑ Kévorkian 2011, pp. 340, 352.

- 1 2 Kévorkian 2011, p. 351.

- ↑ Poghosyan 1996b.

- 1 2 Hagopian 2017a.

- ↑ Hagopian 2017b.

- ↑ Hakobyan 2020.

- ↑ Martirosyan 2020, p. 65.

- ↑ McCarthy, Turan & Taşkıran 2014, pp. 6–7.

- ↑ Kévorkian 2011, p. 277.

- ↑ Kévorkian 2011, p. 280.

- 1 2 Petoyan 1965, p. 326.

- 1 2 Thomas Artsruni 1985, p. 188, (book II, chapter 7).

- 1 2 Hiwbshman 1907, p. 55, n. 3.

- ↑ Thomas Artsruni 1985, pp. 187–188, (book II, chapter 7).

- ↑ Martirosyan 2020, pp. 63–64.

- ↑ A-Dō 1912, p. 120.

- ↑ Mikʻayelyan 1984, p. 202.

- ↑ McCarthy, Turan & Taşkıran 2014, p. 7.

- ↑ McCarthy, Turan & Taşkıran 2014, p. 8.

- ↑ McCarthy, Turan & Taşkıran 2014, p. 9.

- 1 2 3 McCarthy, Turan & Taşkıran 2014, p. 11.

- ↑ Taylor 1865, p. 28.

- ↑ McCarthy, Turan & Taşkıran 2014, p. 13.

Bibliography

- A-Dō (1912). Vani, Bitʻlisi ew Ērzrumi vilayētʻnerě [The Vilayets of Van, Bitlis and Erzurum] (in Armenian). Erewan: Tparan "Kultura". hdl:2027/mdp.39015041464523.

- Adontsʻ, Nikoghayos (1972). Hayastani patmutʻyun: Akunkʻnerě X-VI d.d. m.tʻ.a.: hayeri tsagumě: Hodvatsner [History of Armenia: Origins X–VI Centuries BCE: Origin of the Armenians: Articles] (in Armenian). Translated by Seghbosyan, V. P. Erevan: "Hayastan" hratarakchʻutʻyun. ISBN 99930-75-27-2.

- Badalyan, G. (1996). "Sasun". In Khudaverdyan, Kostandin (ed.). Haykakan hartsʻ hanragitaran (in Armenian). Erevan: Haykakan hanragitaran hratarakchʻutʻyun. pp. 401–402.

- Danielyan, Ē. (1984). "Sasun". In Hambardzumyan, Viktor (ed.). Soviet Armenian Encyclopedia (in Armenian). Vol. 10. Erevan. pp. 199–202.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Eremyan, S. T. (1963). Hayastaně ěst Ashxarhatsʻoytsʻ-i [Armenia according to the Ashkharhatsʻoytsʻ] (in Armenian). Erevan: Armenian SSR Academy of Sciences Publishing.

- Hagopian, Sofia (25 July 2017). "Sassoun and the Armenians of Sassoun after the Genocide and up to this day". Horizon Weekly. Archived from the original on 5 January 2023. Retrieved 10 September 2022.

- Hagopian, Sofia (26 July 2017). "Sassoun and the Armenians of Sassoun after the Genocide and up to this day – part II". Horizon Weekly. Archived from the original on 5 January 2023. Retrieved 10 September 2022.

- Hakobyan, Tʻ. Kh.; Melikʻ-Bakhshyan, St. T.; Barseghyan, H. Kh. (1998). "Sasun". Hayastani ev harakitsʻ shrjanneri teghanunneri baṛaran [Dictionary of toponymy of Armenia and adjacent territories] (in Armenian). Vol. 4. Erevani hamalsarani hratarakchʻutʻyun. pp. 505–506.

- Hakobyan, Sofia (22 May 2020). "Sasuntsʻi kʻahanayi kronapʻokh tʻoṛnuhu patmutʻyuně" [The story of a convert granddaughter of a Sasun priest]. mediamax.am (in Armenian). Archived from the original on 5 January 2023. Retrieved 10 September 2022.

- Haroutyunian, Sargis (1997). "Armenian Epic Tradition and Kurdish Folklore". Iran & the Caucasus. 1: 85–92. doi:10.1163/157338497X00049. JSTOR 4030741.

- Hewsen, Robert H. (1992). The Geography of Ananias of Širak (Ašxarhacʻoycʻ): The Long and the Short Recensions. Wiesbaden: Dr. Ludwig Reichert Verlag. ISBN 3-88226-485-3.

- Hewsen, Robert H. (2001). "The Historical Geography of Baghesh/Bitlis and Taron/Mush". In Hovannisian, Richard G. (ed.). Armenian Baghesh/Bitlis and Taron/Mush. Costa Mesa: Mazda Publishers. ISBN 9781568591360.

- Hiwbshman, H. (1907). Hin Hayotsʻ Teghwoy Anunnerě [Ancient Armenian Place Names] (in Armenian). Translated by Pilējikchean, H. B. Vienna: Mkhitʻarean Tparan.

- Hovannisian, Richard G. (2001). Hovannisian, Richard G. (ed.). Armenian Baghesh/Bitlis and Taron/Mush. Costa Mesa: Mazda Publishers. ISBN 9781568591360.

- Kévorkian, Raymond (2011). The Armenian Genocide: A Complete History. London & New York: I.B. Tauris. ISBN 978-1-84885-561-8.

- Martirosyan, Tigran (2020). "Armenian Demographics of Sassoun in the Late Ottoman Period". Armenian Review. 57 (1–2): 59–91.

- McCarthy, Justin; Turan, Ömer; Taşkıran, Cemalettin (2014). Sasun: The History of an 1890s Armenian Revolt. Salt Lake City. ISBN 978-1-60781-385-9. OCLC 908769524.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Mikʻayelyan, Zh. (1984). "Sasuni barbaṛ" [Sasun dialect]. In Hambardzumyan, Viktor (ed.). Soviet Armenian Encyclopedia (in Armenian). Vol. 10. Erevan. pp. 202–203.

{{cite encyclopedia}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Miller, Owen (2018). "Rethinking the Violence in the Sasun Mountains (1893-1894)". Études arméniennes contemporaines (10): 97–123. doi:10.4000/eac.1556. ISSN 2269-5281.

- Petoyan, V. (1955). "Sasuni Tʻoṛnikian ishkhanutʻyuně" [The Tornikian principality of Sasun]. HSSṚ GA Teghekagir Hasarakakan Gitutʻyunneri (in Armenian) (2): 85–96.

- Petoyan, Vardan (1965). Sasna azgagrutʻyuně [The Ethnography of Sasun] (in Armenian). Erevan: Haykakan SSṚ Gitutʻyunneri Akademia, Hnagitutʻyan ev Azgagrutʻyan Institut ev Hayastani Petakan Patmakan Tʻangaran.

- Poghosyan, H. (1996a). "Sasuni apstambutʻyun" [Sasun uprising]. In Khudaverdyan, Kostandin (ed.). Haykakan hartsʻ hanragitaran (in Armenian). Erevan: Haykakan hanragitaran hratarakchʻutʻyun. pp. 402–404.

- Poghosyan, H. (1996b). "Sasuni inkʻnapashtpanutʻyun 1915" [Sasun self-defense 1915]. In Khudaverdyan, Kostandin (ed.). Haykakan hartsʻ hanragitaran (in Armenian). Erevan: Haykakan hanragitaran hratarakchʻutʻyun. p. 403.

- Poghosyan, H. M. (1985). Hambaryan, A. (ed.). Sasuni patmutʻyun (1750—1918) [History of Sasun (1750–1918)] (PDF) (in Armenian). Erevan: "Hayastan" hratarakchʻutʻyun.

- Shemmassian, Vahram L. (2001). "The Sasun Pandukhts in Nineteenth-Century Aleppo". In Hovannisian, Richard G. (ed.). Armenian Baghesh/Bitlis and Taron/Mush. Costa Mesa: Mazda Publishers. ISBN 9781568591360.

- Taylor, J. G. (1865). "Travels in Kurdistan, with Notices of the Sources of the Eastern and Western Tigris, and Ancient Ruins in Their Neighbourhood". The Journal of the Royal Geographical Society of London. 35: 21–58. doi:10.2307/3698077. ISSN 0266-6235. JSTOR 3698077.

- Tomashēk, V. (1896). Sasun ew Tigrisi aghberatsʻ sahmannerě [Sasun and the Area around the Sources of the Tigris River] (in Armenian). Translated by Pilējikchean, Baṛnabas. Vienna: Mkhitʻarean tparan.

- Toumanoff, Cyril (1961). "Introduction to Christian Caucasian History: II: States and Dynasties of the Formative Period". Traditio. Cambridge University Press. 17: 1–106. doi:10.1017/S0362152900008473. JSTOR 27830424. S2CID 151524770.

- Thomas Artsruni (1985). History of the House of the Artsrunikʻ. Translated by Thomson, Robert W. Detroit: Wayne State University Press. ISBN 0-8143-1784-7.

- Walker, Christopher J. (2001). "The End of Armenian Taron and Baghesh, 1914-1916". In Hovannisian, Richard G. (ed.). Armenian Baghesh/Bitlis and Taron/Mush. Costa Mesa: Mazda Publishers. ISBN 9781568591360.

.svg.png.webp)