| Sambor Ghetto | |

|---|---|

Sambor

Sambor location during the Holocaust in Eastern Europe | |

| Location | Sambir, Western Ukraine |

| Incident type | Imprisonment, slave labor, mass killings, deportations to death camps, extortion |

| Organizations | SS; Schutzmannschaften |

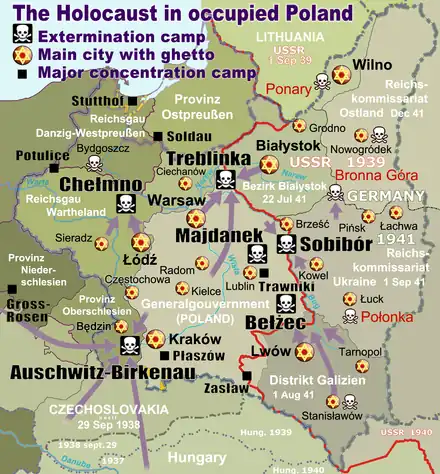

| Camp | Belzec (see map) |

| Victims | Over 10,000 Jews[1] |

Sambor Ghetto (Polish: getto w Samborze, Ukrainian: Самбірське гето, Hebrew: גטו סמבור) was a Nazi ghetto established in March 1942 by the SS in Sambir, Western Ukraine. In the interwar period, the town (Sambor) had been part of the Second Polish Republic. In 1941, the Germans captured the town at the beginning of Operation Barbarossa. According to the Polish census of 1931, Jews constituted nearly 29 percent of the town's inhabitants,[2] most of whom were murdered during the Holocaust. Sambor (Sambir) is not to be confused with the much smaller Old Sambor (Stary Sambor, now Staryi Sambir) located nearby, although the Jewish history of the two is inextricably linked.[3]

Background

When the Second Polish Republic was formed in 1918, both Sambor and Stary Sambor became seats of separate gminas. In 1932, the counties were combined into a single administrative area.[4] The Jewish population grew steadily. Brand new schools, including a Jewish gymnasium and a Bais Yaakov for girls were established, as well as new industrial plants, unions, Jewish relief organizations, and several Zionist parties such as World Agudath Israel. Jews engaged in trade, crafts, carter, agriculture, and professional activities. Jewish cultural institutions included a large library and a sports club.[5] On 8–11 September 1939, Sambor was overrun by the 1st Mountain Division of the Wehrmacht during the Polish Battle of Lwów.[6] It was transferred to the Soviet Union in accordance with the German-Soviet Frontier Treaty signed on 28 September 1939.[6]

After the Soviet takeover, wealthy and middle-class Polish Jews were arrested by the NKVD and sentenced for deportation to Siberia along with the Polish intelligentsia. Some pro-Soviet Jews were given government jobs.[7] The economy was nationalized; hundreds of citizens were executed out of sight by the secret police as "enemies of the people".[7][8] Sambor became part of the Drohobych Oblast on 4 December 1939.[4]

On 22 June 1941, Germany invaded the Soviet Union in Operation Barbarossa. During the hasty evacuation of the political prison in Sambor, the NKVD shot 600 prisoners;[9] 80 corpses were left unburied for lack of time.[8] Sambor was taken over by the Wehrmacht on 29 June.[10] The city became one of a dozen administrative units of the District of Galicia, the fifth district of the General Government, with the capital in Lemberg.[11]

Arriving German troops were accompanied by Ukrainian task forces (pokhidny hrupy) indoctrinated at German training bases in the General Government.[12] The OUN followers (Anwärters included) mobilized Ukrainian militants in some 30 locations at once,[13] including in Sambor, and in accordance with the Nazi theory of Judeo-Bolshevism, launched retaliatory pogroms against the Polish Jews. The deadliest of them, overseen by SS-Brigadeführer Otto Rasch, took place in Lwów beginning 30 June 1941.[14] On 1 July 1941, the Ukrainian nationalists killed approximately 50–100 Polish Jews in Sambor,[5][10][15] but similar pogroms affected other Polish provincial capitals as far as Tarnopol, Stanisławów and Łuck.[16]

The ghetto

The German authorities forced all adult Jews to wear the yellow badge. In July 1941, a Judenrat was formed in Sambor on German orders, with Dr. Shimshon (Samson) Schneidscher as its chairman.[17] In the following months, Jews were deported to the open-type ghetto in Sambor from the entire county.[10] On 17 July, Heinrich Himmler decreed the formation of the Schutzmannschaften from among the local Ukrainians,[16] owing to good relations with the local Ukrainian Hilfsverwaltung.[18] By 7 August 1941, in most areas conquered by the Wehrmacht,[13] units of the Ukrainian People's Militia had already participated in a series of so-called "self-purification" actions, followed closely by killings carried out by Einsatzgruppe C.[15] The OUN-B militia spearheaded a day-long pogrom in Stary Sambor.[3] Thirty-two prominent Jews were dragged by the nationalists to the cemetery and bludgeoned. Surviving eyewitnesses, Mrs. Levitski and Mr. Eidman, reported cases of dismemberment and decapitation.[3] Afterwards, a Jewish Ghetto Police was set up, headed by Hermann Stahl.[5] Jews were ordered to hand over their furs, radios, silver and gold.[17]

Among the people trapped in the Sambor Ghetto were thousands of refugees who arrived there in an attempt to escape the German occupation of western Poland, and possibly cross the border to Romania[5] and Hungary.[19] Confined to the Blich neighbourhood of Sambor – the ghetto was sealed off from the outside on 12 January 1942,[17][20]. Jews from different parts of the city, along with inhabitants of neighbouring communities,[10] including Stary Sambor, were transferred to the ghetto until March 1942. A curfew was imposed, subject to shoot-on-sight enforcement.[3][5]

Deportations to death camps

In July 1942, the first killing centre of Operation Reinhard built by the SS at Belzec (just over 100 kilometres away) began its second phase of extermination, with brand new gas chambers built of brick.[21] Sambor Jews were rounded up in stages. A terror operation was conducted in the ghetto on 2–4 August 1942 ahead of the first deportation.[20] The 'resettlement' rail transports to Belzec left Sambor on 4–6 August 1942 under heavy guard, with 6,000 men, women, and children crammed into Holocaust trains without food or water.[1] About 600 Jews were sent to the Janowska concentration camp nearby.[10] The second set of trains with 3,000–4,000 Jews departed on 17–18 and 22 October 1942.[1][22] On 17 November 1942, the depopulated ghetto was filled with expellees from Turka and Ilnik. Some Jews escaped to the forest. The town of Turka was declared Judenfrei on 1 December 1942.[23] Irrespective of deportations, mass shootings of Jews were also carried out.[7][24] In January 1943, the Germans and Ukrainian Auxiliary Police rounded up 1,500 Jews deemed 'unworthy of life'. They were trucked to the woods near Radlowicz (Radłowicze, Radlovitze; now Ralivka) and shot one by one.[23] Among those still alive in the ghetto, death by starvation and typhus raged.[23]

After the long winter, new terror operations in the ghetto took place in March[23] or April 1943.[3] The Gestapo utilized Wehrmacht units transiting through Sambor to round up Jews. All houses, cellars and even chimneys were searched.[3] The 1,500 captives were split in groups of 100 each.[23] They were escorted to the cemetery,[25] where Jewish men were forced to dig mass graves.[26] The liquidation of the ghetto was approaching. In June, Dr. Zausner, deputy to the Judenrat chairman, gave a speech full of hope because the Gestapo office in Drohobicz agreed to save a group of labourers in exchange for a huge ransom. Nevertheless, on the night of 8 June 1943, the Ukrainian Hilfspolizei set the ghetto houses on fire. In the morning, all Jewish slave labourers were escorted to prison, loaded onto lorries and trucked to the killing fields at Radłowicze.[3] The ghetto was no more; the city was declared "Judenrein". The Soviet Red Army liberated Sambor a year later amid heavy fighting with the retreating Germans, around 7 August 1944.[3][27]

Some Jews had managed to dig a tunnel leading to a sewer out of the ghetto and escaped to the partisans in the forest.[23] A number of local gentiles aided some of the escapees. Those declared Righteous Among the Nations who helped Sambor Ghetto's Jews included the Plewa family,[19][28][29] Celina Kędzierska,[30] the Bońkowski family[31] and the Oczyński family.[32]

In 1943, the Nazi police executed at least 27 people in Sambor for attempting to hide Jews.[33] Altogether, about 160 Jews survived, mostly by hiding with Poles and Ukrainians in the town or the surrounding countryside.[34]

Post-war

After the war, several members of the town's German civilian administration and security apparatus received prison sentences; others did not.[34]

"During the Soviet era, the Jewish cemetery of Sambor lost its original function and was levelled. Plans were made to construct a sports field on the site."[25] Since 1991, Sambir (Самбір) has been part of Ukraine. In 2000, attempts to preserve the site of the mass shootings for a Holocaust memorial park were halted.[25] In 2019, a deal was reached with the local village to allow the memorial to be built.[35]

Seel also

References

- 1 2 3 ARC (2004). "Holocaust Transports". Deportations of Jews from District Galicia to Death Camp in Belzec.

- ↑ Polish census of 1931, Lwów Voivodeship (volume 68). "Sambor population, total" (PDF). Main Bureau of Statistics. pp. 44–45 (75–76 in PDF download).

The city of Sambor: 21,923 inhabitants, with 13,575 ethnic Poles, and 6,274 Jews, as well as 1,338 ethnic Ukrainians and 1,564 ethnic Ruthenians (i.e. Rusyns) determined by mother tongue (Yiddish: 4,942 and Hebrew: 383). Sambor county (powiat): population 133,814 in 1931 (urban and rural) with 11,258 Jews.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help)CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) For the current population numbers within Ukraine see: "Population of Ukraine as of January 1, 2016" (PDF). Statistical Collected Book Available. State Statistics Service of Ukraine; Institute for Demography and Social Studies: 55, 52. Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 July 2016. Retrieved 6 September 2016.м. Самбір: 35,026 – м. Старий Самбір: 6,648.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Alexander Manor. "Liquidation of the Jewish Community of Stari-Sambor; June and August 1942 deportations". The Book of Sambor and Stari Sambor, History of the Cities. Translated by Sara Mages. JewishGen Inc. Yizkor Book Project.

- 1 2 Starostwo Powiatowe w Ustrzykach Dolnych. "Miasto Stary Sambor" [The city of Old Sambor]. Sister cities. Ustrzyki Dolne: Powiat Bieszczadzki.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Encyclopedia of the Ghettos (2016). "סמבּוֹר (Sambor) המכון הבין-לאומי לחקר השואה – יד ושם". Yad Vashem. The International Institute for Holocaust Research.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - 1 2 Steve J. Zaloga (2002). Poland 1939: The Birth of Blitzkrieg. Oxford: Osprey Publishing / Praeger. p. 79. ISBN 0-275-98278-5. Also in: Marcin Hałaś. "Sambor". Polska Niepodległa. Source: Stanisław Sławomir Nicieja (2014), Kresowa Atlantyda. Historia i mitologia miast kresowych. Volume V, Wydawnictwo MS, Opole. Archived from the original on 27 August 2016 – via Internet Archive.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - 1 2 3 Meylakh Sheykhet. "Sambir (Sambor)". Ukraine: Faina Petryakova Scientific Center for Judaica and Jewish Art. [sources not listed]

- 1 2 Тов. Сергиенко. "Доповідна записка наркому Сергієнко про розстріли та евакуацію в'язнів із тюрем Західної України 5 липня1941 р." [Shooting and evacuating prisoners from prisons in Western Ukraine Report by Commissar Serhiyenko] (PDF). Народному комиссару внутренних дел УССР старшему майору государственной безопасности. Киев. Page 171 in PDF document – via direct download.

В двух тюрьмах в городе Самбор и Стрий (сведений о тюрьме в гор. Перемышль не имеем) – содержалось 2242 заключенных. Во время эвакуации расстреляно по обеим тюрьмам 1101 заключенных, освобождено – 250 человек, этапировано 637 и оставлено в тюрьмах – 304 заключенных. 27 июня при эвакуации в тюрьме гор. Самбор осталось – 80 незарытых трупов, на просьбы начальника тюрьмы к руководству Горотдела НКГБ и НКВД оказать ему помощь в зарытии трупов – они ответили категорическим отказом.

- ↑ Roger Moorhouse (2014). The Devils' Alliance: Hitler's Pact with Stalin, 1939–1941. Basic Books. p. 176. ISBN 978-0-465-05492-3.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Eugene Shnaider (2015). "Самбор, Львовская область". Еврейские местечки Украины. Самбор.

29 июня 1941 Самбор оккупировали части вермахта. 1 июля 1941 местные украинцы устроили погром, в ходе которого было убито 50 евреев.

- ↑ Nancy E. Rupprecht; Wendy Koenig (2015). Global Perspectives on the Holocaust: History. Cambridge Scholars Publishing. pp. 368–369. ISBN 978-1-4438-8424-2.

Kreishauptmannschaften in Distrikt Galizien.

- ↑ Irena Cantorovich (June 2012). "Honoring the Collaborators – The Ukrainian Case" (PDF). Roni Stauber, Beryl Belsky. Kantor Program Papers.

When the Soviets occupied eastern Galicia, some 30,000 Ukrainian nationalists fled to the General Government. In 1940 the Germans began to set up military training units of Ukrainians, and in the spring of 1941 Ukrainian units were established by the Wehrmacht.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) See also: Marek Getter (1996). "Policja Polska w Generalnym Gubernatorstwie 1939–1945". Polish Police in the General Government 1939–1945. Przegląd Policyjny nr 1-2. Wydawnictwo Wyższej Szkoły Policji w Szczytnie. pp. 1–22. Archived from the original (WebCite cache) on 26 June 2013.Reprint, with extensive statistical data, at Policja Państwowa webpage.

{{cite web}}: External link in|quote= - 1 2 Р. П. Шляхтич (2006). ОУН в 1941 році: документи: В 2-х частинах Ін-т історії України НАН України [OUN in 1941: Documents in 2 volumes] (PDF). Kiev: Ukraine National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine: Institute of History of Ukraine. pp. 426–428. ISBN 966-02-2535-0.

Abstract. Listed locations included Lviv, Ternopil, Stanislavov, Lutsk, Rivne, Yavoriv, Kamenetz-Podolsk, Drohobych, Borislav, Dubno, Sambor, Kostopol, Sarny, Kozovyi, Zolochiv, Berezhany, Pidhaytsi, Kolomyya, Rava-Ruska, Obroshyno, Radekhiv, Gorodok, Kosovo, Terebovlia, Vyshnivtsi, Zbarazh, Zhytomyr and Fastov.

{{cite book}}: External link in|quote= - ↑ Tadeusz Piotrowski (1998). Poland's Holocaust: Ethnic Strife, Collaboration with Occupying Forces and Genocide in the Second Republic, 1918–1947. McFarland. pp. 207–211. ISBN 0-7864-0371-3 – via Google Books.

- 1 2 Peter Longerich (2010). Holocaust: The Nazi Persecution and Murder of the Jews. OUP Oxford. pp. 195, 199–200. ISBN 978-0-19-280436-5.

- 1 2 Symposium Presentations (September 2005). "The Holocaust and [German] Colonialism in Ukraine: A Case Study" (PDF). The Holocaust in the Soviet Union. The Center for Advanced Holocaust Studies of the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. pp. 15, 18–19, 20 in current document of 1/154. Archived from the original on 16 August 2012. Retrieved 7 December 2014.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) See also: Ronald Headland (1992). Messages of Murder: A Study of the Reports of the Einsatzgruppen of the Security Police and the Security Service, 1941–1943. Fairleigh Dickinson Univ. Press. pp. 79, 125–126. ISBN 0-8386-3418-4. - 1 2 3 Alexander Manor; Toni Nacht; Dolek Frei (1980). "The Annihilation of the City". The Book of Sambor and Stari Sambor; a Memorial to the Jewish Communities. Translated by Susan Rosin. Chapter 8.

- ↑ Markus Eikel (2013). "The local administration under German occupation in central and eastern Ukraine, 1941–1944". The Holocaust in Ukraine: New Sources and Perspectives (PDF). Center for Advanced Holocaust Studies, United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. Pages 110–122 in PDF.

Ukraine differs from other parts of the German-occupied Soviet Union, whereas the local administrators have formed the Hilfsverwaltung in support of extermination policies in 1941 and 1942, and in providing assistance for the deportations to camps in Germany, mainly in 1942 and 1943.

- 1 2 World Holocaust Remembrance Center (2016). Rescue Story: Plewa, Alojzy. Yad Vashem.

- 1 2 Allen Brayer (2010). Hiding In Death's Shadow. iUniverse. pp. 71–72. ISBN 978-1-4502-6383-2.

- ↑ Andrzej Kola (2015) [2000]. Belzec. The Nazi Camp for Jews in the Light of Archaeological Sources. Translated from Polish by Ewa Józefowicz and Mateusz Józefowicz. Warsaw-Washington: The Council for the Protection of Memory of Combat and Martyrdom – The United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. ISBN 978-83-905590-6-3. Also in: Archeologists reveal new secrets of Holocaust, Reuters News, 21 July 1998.

- ↑ Michael Peters (2016) [2004]. "Ghetto List". ARC. Archived from the original on 3 March 2016 – via Internet Archive.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) Virtual Shtetl (2016). "Glossary of 2,077 Jewish towns in Poland". Museum of the History of the Polish Jews. Archived from the original on 8 February 2016. Gedeon (2012) [2004]. "Getta Żydowskie". Izrael. Badacz.org. Sampol. Archived from the original on 22 November 2012 – via Internet Archive.{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) See also: Yitzhak Arad (1987). Belzec, Sobibor, Treblinka: The Operation Reinhard Death Camps. Indiana University Press. ISBN 0-253-34293-7.Deportations to Belzec from Sambor, 4–6 August 1942: 4,000 Jews; 17–18 October: 2,000 and 22 October 1942: 2,000 Jews. Stary Sambor deportation, 5–6 August: 1,500.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Allen Brayer (2010). Hiding In Death's Shadow: How I Survived The Holocaust. iUniverse. pp. 72, 73. ISBN 978-1-4502-6383-2.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ↑ Robin O'Neil. "Extermination of Jews in General Government 1943 Following Closure of Belzec". A Reassessment: Resettlement Transports to Belzec. JewishGen Yizkor Book Project.

Sambor, March 1943: 900[372] April 1943: 1000[390] June 1943: 100s[422]

- 1 2 3 Nadja Weck (2015). Nancy E. Rupprecht; Wendy Koenig (eds.). Holocaust Memory in Western Ukraine. Cambridge Scholars Publishing. p. 367. ISBN 978-1-4438-8424-2.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ↑ Yaroslav G., witness N°750 (13 January 2009). Execution of Jews in Sambir. Interview. Sambir: YAHAD-IN UNUM. Exhibit 5.

{{cite AV media}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ↑ PKWN (8 August 1944). "Wojska I-go frontu ukrainskiego 7 VIII szturmem zajely miasto Sambor". Lublin: Rzeczpospolita, Organ Polskiego Komitetu Wyzwolenia Narodowego.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ↑ "Plewa FAMILY". db.yadvashem.org. Retrieved 18 June 2019.

- ↑ Magdalena Stankowska (May 2012). "The Plewa Family". Przywracanie Pamięci. Translated by Joanna Sliwa. Polish Righteous – Polscy Sprawiedliwi. Archived from the original on 15 September 2016. Retrieved 8 September 2016.

- ↑ ""Be a good person". The story of Sister Celina Aniela Kędzierska | Polscy Sprawiedliwi". sprawiedliwi.org.pl. Retrieved 12 June 2019.

- ↑ "Bońkowski FAMILY". db.yadvashem.org. Retrieved 18 June 2019.

- ↑ Yad Vashem. "Oczyński FAMILY; Oczyński Jan and Oczyński Mieczysław (1914 – ), SON". Rescue Story. The Righteous Among The Nations.

- ↑ И.А. Альтман (2002). Холокост и еврейское сопротивление на оккупированной территории СССР. Центр и Фонд «Холокост». ISBN 5-88636-007-7.

- 1 2 Kruglov, Alexander; Patt, Avinoam (2012). "Sambor". In Megargee, Geoffrey P. (ed.). Encyclopedia of camps and ghettos, 1933-1945. Indiana University Press. pp. 824–826. ISBN 978-0-253-35428-0. OCLC 823622869.

- ↑ "Did Canada honour Nazi allies or support a Jewish cemetery?". 20 September 2019.