The Russian Empire gradually entered World War I during the three days before July 28, 1914. This began with Austria-Hungary's declaration of war on Serbia, a Russian ally. Russia sent an ultimatum, via Saint Petersburg, to Vienna, warning Austria-Hungary not to attack Serbia. Following the invasion of Serbia, Russia began to mobilize the reserve army on the border of Austria-Hungary. Consequently, on July 31, Germany demanded Russian demobilization. There was no response, which resulted in the German declaration of war on Russia on the same day (August 1, 1914). Per its war plan, Germany disregarded Russia and moved first against France, declaring war on August 3. Germany sent its main armies through Belgium to surround Paris. The threat to Belgium caused Britain to declare war on Germany on August 4.[1][2] The Ottoman Empire soon joined the Central Powers and fought Russia along their border.[3]

Historians researching the causes of World War I have emphasized the role of Germany and Austria-Hungary. Scholarly consensus has typically minimized Russian involvement in the outbreak of this mass conflict. Key elements were Russia's defense of Orthodox Serbia, its pan-Slavic roles, its treaty obligations with France, and its concern with protecting its status as a world power. However, historian Sean McMeekin emphasizes Russian plans to expand its empire southward and to seize Constantinople (modern-day Istanbul) as an outlet to the Mediterranean Sea.[4]

Archduke Franz Ferdinand, the heir to the Austro-Hungarian throne, was assassinated by Bosnian Serbs on June 28, 1914, due to Austria-Hungary's annexation of the mainly Slavic province. Though Austria-Hungary couldn't find evidence that the Serbian state had sponsored this assassination, it issued an ultimatum to Serbia during the July Crisis one month later, assuming it would be rejected and thus lead to war. Austria-Hungary deemed Serbia deserving of punishment for the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand. Although Russia had no formal treaty obligation to Serbia, it stressed its desire to control the Balkans, having a long-term perspective toward gaining a military advantage over Germany and Austria-Hungary. Russia was incentivized to delay militarization, and most Russian leaders wanted to avoid war. However, Russia had yielded French support and feared that a failure to defend Serbia would harm Russian credibility, constituting a major political defeat in its goal of controlling the Balkans.[5] Tsar Nicholas II mobilized Russian forces on July 30, 1914, to threaten Austria-Hungary if it invaded Serbia. Historian Christopher Clark believes that the "Russian general mobilization [of July 30] was one of the most momentous decisions of the August crisis". The first general mobilization occurred before the German government declared a state of impending war.[6]

Russia's threats against Germany resulted in military action by German forces, which followed through with its mobilization and a declaration of war on August 1, 1914. At the outset of hostilities, Russian forces led offensives against Germany and Austria-Hungary.[7]

Background

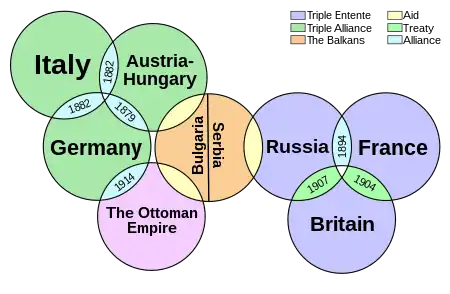

Between 1873 and 1887, Russia was allied with Germany and Austria-Hungary in the League of the Three Emperors, and then with Germany in the 1887–1890 Reinsurance Treaty. Both collapsed because of the competing interests of Austria-Hungary and Russia in the Balkans. France took advantage of this, agreeing to the 1894 Franco-Russian Alliance, but Britain viewed Russia with deep suspicion because of the Great Game. In 1800, over 3,000 kilometres (1,900 mi) separated Russia and British India, but by 1902, it was lessened to 30 kilometres (19 mi) with Russian advances into Central Asia.[8] The proximity threatened to bring the two powers into conflict along with the long-held Russian objective of gaining control of the Bosporus Straits, and with it access to the British-dominated Mediterranean Sea.[9]

Britain's isolation during the 1899–1902 Second Boer War and Russia being defeated in the 1905 Russo-Japanese War led both parties to seek allies. The Anglo-Russian Convention of 1907 settled disputes in Asia and allowed the establishment of the Triple Entente with France, which was largely informal. In 1908, Austria-Hungary annexed the former Ottoman province of Bosnia and Herzegovina, prompting the Russian response of the Balkan League to prevent further Austrian expansion.[10]

In the 1912–1913 First Balkan War, Serbia, Bulgaria, and Greece captured most of the remaining Ottoman possessions in Europe. Disputes over their division resulted in the Second Balkan War, in which Bulgaria was comprehensively defeated by its former allies. This defeat turned Bulgaria into a revanchist local power, which fueled a second opportunity to fulfill its national aspirations. This left Serbia as the most important Russian ally in the region.

Russia's industrial base and railway network had significantly improved since 1905, but from a relatively low base. In 1913, Nicholas II increased the Russian army of over 500,000 men. Although there was no formal alliance between Russia and Serbia, their close bilateral links provided Russia a route into the crumbling Ottoman Empire, where Germany also had significant interests. Combined with the increase in Russian military strength, Austria-Hungary and Germany felt threatened by Serbia's expansion. When Austria invaded Serbia on July 28, 1914, Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Sazonov viewed it as an Austro-German conspiracy to end Russian influence in the Balkans.[11]

On July 30, Russia declared a general mobilization in support of Serbia. The next day, on August 1, 1914, Germany declared war on Russia, followed by Austria-Hungary on August 6. Russia and the Entente declared war on the Ottoman Empire in November 1914 after Ottoman warships bombarded the Black Sea port of Odesa in late October.[12]

Major players

Most historians agree that Russia's top military leadership was generally tremendously incompetent.[13] Tsar Nicholas II made all final decisions but was repeatedly given conflicting advice by his peers, resulting in unsound decision-making throughout his time in power. He set up a seriously flawed organizational structure that proved inadequate for the high pressures and wartime's instant demands. The British historian David Stevenson, for example, points to the "disastrous consequences of deficient civil-military liaison," in which civilians and generals were not in contact with each other. The government was unaware of its fatal weaknesses and remained out of touch with public opinion. The Foreign Minister had to warn Nicholas that "unless he yielded to the popular demand and unsheathed the sword on Serbia's behalf, he would run the risk of revolution and the loss of his throne." Nicholas yielded but lost his throne. Stevenson concludes:

Russian decision-making in July 1914 was more truly a tragedy of miscalculation... a policy of deterrence that failed to deter. Yet, like Germany, it too rested on the assumption that war was possible without domestic breakdown and that it could be waged with a reasonable prospect of success. Russia was more vulnerable to social upheaval than any other power. Its socialists were more estranged from the existing order than those elsewhere in Europe, and a strike wave among the industrial workforce reached a crescendo with the general stoppage in St. Petersburg in July 1914.[14]

Foreign Minister Sergei Sazonov was not a powerful figure in the events leading up to Russia's entry into World War I, nor did he play a consequential role in Russia's decisions following their entry. According to historian Thomas Otte, "Sazonov felt too insecure to advance his positions against stronger men... Tsar Nicholas II tended to yield rather than press home his views... At the critical stages of the July crisis, Sazonov was inconsistent and showed an uncertain grasp of international realities."[15]

French ambassador Maurice Paléologue quickly became influential by repeatedly promising France would go to war alongside Russia, which reflected the position of President Raymond Poincaré.[16]

Serious planning for a future war was practically impossible because of the complex rivalries and priorities given to royalty. The main criteria for high command were linkage to the royalty rather than expertise. Though the General Staff had the expertise, it was often outweighed by the elite Imperial Guards, a favorite bastion of the aristocracy that prized throwing parades over planning large-scale military maneuvers. This led to the grand dukes inevitably gaining high command.[17]

French alliance

Russia depended heavily on the French alliance since Germany would have greater difficulty fighting a two-front war than one with Russia alone. The French ambassador, Maurice Paléologue, despised Germany and saw that when war broke out, France and Russia had to be close allies against Germany. His approach agreed with French President Raymond Poincaré. Unconditional French support to Russia was promised in the unfolding crisis with Germany and Austria-Hungary. Historians debate whether Paléologue exceeded his instructions but agree that he failed to inform Paris of what was happening exactly, not warning that Russian mobilization might launch a world war.[18][19][20]

Beginning of the war

On June 28, 1914, Archduke Franz Ferdinand of Austria was assassinated in Sarajevo, and Tsar Nicholas II vacillated as to Russia's course of action. A relatively new factor influencing Russian policy was the growth of Pan-Slavism, which identified Russia's duty to all Slavs, especially those who practiced impulse shifted attention away from the Ottoman Empire and toward the threat posed to the Slavic people by Austria-Hungary. Serbia identified itself as the champion of the Pan-Slavic ideal, and Austria-Hungary planned to destroy Serbia for that reason.[21] Nicholas wanted to defend Serbia, but not to fight a war with Germany. In a series of letters exchanged with Kaiser Wilhelm of Germany (the so-called "Willy–Nicky correspondence"), both cousins proclaimed their desire for peace, and each attempted to get the other to back down. Nicholas desired Russia's mobilization to be only against Austria-Hungary to avoid war with Germany. The Kaiser, however, had pledged to support Austria-Hungary.

On July 25, 1914, Nicholas decided to intervene in the Austro-Serbian conflict, a step toward general war. He put the Russian army on "alert" on July 25. Although it was not a general mobilization, the German and Austro-Hungarian borders were threatened and looked like military preparation for war. However, the Russian Army had few workable plans and no contingency plans for a partial mobilization. On July 30, 1914, Nicholas took the fateful step of confirming the order for general mobilization, despite being very reluctant.[22]

On July 28, Austria-Hungary formally declared war against Serbia.[23][24] Count Witte told the French Ambassador Maurice Palaeologus that the Russian point of view considered the war to be madness, Slavic solidarity to be simply nonsense and nothing could be hoped by war.[25]

On July 30, Russia ordered general mobilization but maintained that it would not attack if peace talks began. Reacting to the discovery of Russian partial mobilization ordered on July 25, Germany announced its pre-mobilization posture, the imminent danger of war. Germany told Russia to demobilize within twelve hours. In St. Petersburg, at 7 p.m., the German ultimatum to Russia expired. The German ambassador to Russia met Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Sazonov, asked three times if Russia would reconsider, and delivered the note accepting Russia's war challenge and declaring war on August 1. On August 6, Franz Joseph I of Austria signed the Austro-Hungarian declaration of war against Russia.[26]

At the outbreak of war, each of the European powers began to publish selected, and sometimes misleading, compendia of diplomatic correspondence, seeking to establish justification for their own entry into the war and to cast blame on other actors.[27] The first of these color books to appear was the German White Book[28] which appeared on August 4, 1914, the same day as Britain's war declaration.[29][30] The British Blue Book came out two days later,[31] followed by the Russian Orange Book in mid-August.[29]

Military weaknesses

The outbreak of war on August 1, 1914, found Russia grossly unprepared.[32] The Allies placed their faith in the Russian army. Its pre-war regular strength was 1,400,000, and mobilization added 3,100,000 reserves. In every other aspect, however, Russia was unprepared for war. Germany had ten times as much railway track per km2, and Russian soldiers traveled an average of 1,290 kilometres (800 mi) to reach the front, but German soldiers traveled less than a quarter of that distance to get to the front. Russian heavy industry was not large enough to equip the massive armies that the Tsar could raise, and its reserves of munitions were small. While the German army in 1914 was better equipped than any other man-for-man, the Russian army was severely short on artillery pieces, shells, motorized transports, and boots.[33]

Before the war, Russian planners had neglected the critical logistical issue of how the Allies could ship supplies and munitions to Russia. With the Baltic Sea barred by German U-boats and surface ships and the Dardanelles by the guns of Germany's ally, the Ottoman Empire, Russia initially could receive help only via Arkhangelsk, which was frozen solid in winter, or via Vladivostok, which was over 6,400 kilometres (4,000 mi) from the front line. By 1915, a new rail line was begun, which gave access to the ice-free port of Murmansk by 1917.[34]

The Russian High Command was severely weakened by the mutual contempt between War Minister Vladimir Sukhomlinov and Grand Duke Nicholas, who commanded the armies in the field. However, an immediate attack was ordered against the German province of East Prussia. The Germans efficiently mobilized there, defeating the two Russian armies that invaded. The Battle of Tannenberg, where the entire Russian Second Army was annihilated, cast an ominous shadow over the empire's future. The loyal officers who lost were the very ones that were needed to protect the dynasty. The Russian armies had some success against both the Austro-Hungarian and the Ottoman Armies, but the German Army steadily pushed them back. In September 1914, to relieve pressure on France, the Russians were forced to halt a successful offensive against Austria-Hungary in Galicia to attack German-held Silesia.[35]

The main Russian goal was focused on the Balkans and especially taking control of Constantinople (Istanbul). The Ottoman entry into the war opened up new opportunities, but Russia was too hard-pressed to exploit them. Instead, the government incited Britain and France to the action at Gallipoli, which failed badly. Russia then incited a rebellion by the Armenians, who were massacred in one of the great atrocities of the war, the Armenian genocide. The combination of poor preparation and poor planning destroyed the morale of Russian troops and set the stage for the collapse of the entire regime in early 1917.[36]

Gradually, a war of attrition set in on the vast Eastern Front; the Russians were facing the combined forces of Germany and Austria-Hungary and suffered staggering losses. General Anton Denikin, retreating from Galicia wrote:

The German heavy artillery swept away whole lines of trenches and their defenders with them. We hardly replied. There was nothing with which we could reply. Our regiments, although completely exhausted, were beating off one attack after another by bayonet... Blood flowed unendingly, the ranks became thinner and thinner and thinner. The number of graves multiplied.[37]

Legacy

Historians on the origin of the First World War have emphasized the role of Germany and Austria-Hungary. The consensus of scholars includes scant mention of Russia and only brief mentions of Russia's defense of Serbia, its Pan-Slavic roles, its treaty obligations with France, and its concern for protecting its status as a great power.[4]

However, the historian Sean McMeekin has emphasized Russia's aggressive expansionary goal to the south. He argues that for Russia, the war was ultimately about the Ottoman Empire and that the Foreign Ministry and Army were planning a war of aggression from at least 1908 and perhaps even 1895. He emphasizes that the immediate goal was to seize Constantinople and an outlet to the Mediterranean by control of the Dardanelles and Bosporus straits.[38] Reviewers have generally been critical of McMeekin's revisionist interpretation.[39][40]

See also

References

- ↑ Reynolds; Churchill; Miller (February 19, 2016). The Story of the Great War. Vol. 4: The World War. VM eBooks.

- ↑ Bloch, Ben. "100 years ago a book of the 50,000 UK Jews who fought in the WWI was presented to the King". The Jewish Chronicle. Retrieved September 16, 2022.

- ↑ Cengizer, Altay (February 12, 2022). Incipient Awareness - The First World War and the End of the Ottoman Empire. Transnational Press London. ISBN 978-1-801-35092-1.

- 1 2 McMeekin 2011, pp. 2–5

- ↑ Levy & Mulligan 2017, pp. 731–769.

- ↑ Clark 2013, p. 509.

- ↑ Lincoln 1986, pp. 23–59.

- ↑ Hopkirk, Peter (1990). The Great Game; On Secret Service in High Asia (1991 ed.). Oxford University Press. pp. 4–5. ISBN 978-0-719-56447-5.

- ↑ Dennis 1922, pp. 728–729.

- ↑ Stowell 1915, p. 94.

- ↑ Jelavich 2004, p. 262.

- ↑ Mustafa, Aksakal (2012). "War as a Saviour? Hopes for War & Peace in Ottoman Politics Before 1914". In Afflerbach, Holger; Stevenson, David (eds.). An Improbable War? the Outbreak of World War I and European Political Culture Before 1914. Berghahn Books. p. 293. ISBN 978-0-857-45310-5.

- ↑ Lieven 1983, pp. 51–140.

- ↑ Stevenson 1988, pp. 31–32.

- ↑ Otte 2015, pp. 123–124.

- ↑ Vasquez, John A. (November 22, 2018). Contagion and War: Lessons from the First World War. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-108-41704-4.

- ↑ Gatrell 2015, pp. 674–677.

- ↑ Hamilton & Herwig 2004, pp. 121–122.

- ↑ Clark 2013, pp. 435–450, 480–484.

- ↑ Fay 1930, pp. 443–446, Vol. II.

- ↑ Boeckh, Katrin (2016). "The Rebirth of Pan-Slavism in the Russian Empire, 1912–13". In Boeckh, Katrin; Rutar, Sabine (eds.). The Balkan Wars from Contemporary Perception to Historic Memory. pp. 105–137. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-44642-4_5. ISBN 978-3-319-44641-7.

- ↑ Hosch, William L. (December 20, 2009). World War I: People, Politics, and Power. The Rosen Publishing Group, Inc. ISBN 978-1-61530-013-6.

- ↑ Strachan 2003, p. 85.

- ↑ Hamilton, Richard F.; Herwig, Holger H., eds. (2003). Origins of World War One. p. 514.

- ↑ Massie, Robert K. (1967). Nicholas and Alexandra: The Fall of the Romanov Dynasty. Random House Publishing. p. 299. ISBN 978-0-679-64561-0.

- ↑ Lanser, Amanda (December 15, 2015). World War I Leaders. ABDO. ISBN 978-1-68077-106-0.

- ↑ Hartwig, Matthias (May 12, 2014). "Colour books". In Bernhardt, Rudolf; Bindschedler, Rudolf; Max Planck Institute for Comparative Public Law and International Law (eds.). Encyclopedia of Public International Law. Vol. 9 International Relations and Legal Cooperation in General Diplomacy and Consular Relations. Amsterdam: North-Holland. p. 24. ISBN 978-1-4832-5699-3. OCLC 769268852.

- ↑ von Mach, Edmund (1916). Official Diplomatic Documents Relating to the Outbreak of the European War: With Photographic Reproductions of Official Editions of the Documents (Blue, White, Yellow, Etc., Books). New York: Macmillan. p. 7. LCCN 16019222. OCLC 651023684.

- 1 2 Schmitt, Bernadotte E. (April 1, 1937). "France and the Outbreak of the World War". Foreign Affairs. Council on Foreign Relations. 26 (3): 516–536. doi:10.2307/20028790. JSTOR 20028790. Archived from the original on November 25, 2018.

- ↑ Schmitt 1937.

- ↑ Beer, Max (1915). "Das Regenbogen-Buch": deutsches Wiessbuch, österreichisch-ungarisches Rotbuch, englisches Blaubuch, französisches Gelbbuch, russisches Orangebuch, serbisches Blaubuch und belgisches Graubuch, die europäischen Kriegsverhandlungen [The Rainbow Book: German White Book, Austrian-Hungarian Red Book, English Blue Book, French Yellow Book, Russian Orange Book, Serbian Blue Book and Belgian Grey Book, the European war negotiations] (2nd, improved ed.). Bern: F. Wyss. p. 23. OCLC 9427935. Retrieved October 4, 2020.

- ↑ Wildman 1980.

- ↑ Strachan 2004, pp. 297–316.

- ↑ Pipes 2011, p. 207.

- ↑ Strachan 2004, pp. 316–335.

- ↑ McMeekin 2011, pp. 115–174.

- ↑ Tames, Richard (1972). Last of the Tsars: The Life and Death of Nicholas and Alexandra. Pan Books. p. 46. ISBN 0-330-02902-9.

- ↑ McMeekin 2011, pp. 27, 29, 101.

- ↑ Frary 2012.

- ↑ Mulligan 2014.

Further reading

Books

- Albertini, Luigi (1953). The Origins of the War of 1914. Vol. 2. Translated by Massey, Isabella M. Oxford University Press.

- Aleksinsky, Grigory (1915). Russia and the great war. pp. 1–122.

- Bobroff, Ronald P. (2006). Roads to Glory: Late Imperial Russia and the Turkish Straits. I.B. Tauris. ISBN 978-1-350-17540-2.

- Bobroff, Ronald P. (2014). "War Accepted but Unsought: Russia's Growing Militancy and the July Crisis, 1914". In Levy, Jack S.; Vasquez, John A. (eds.). The Outbreak of the First World War. Cambridge University Press. pp. 227–251. ISBN 978-1-107-33699-5.

- Brandenburg, Erich (1933). From Bismarck to the World War: A History of German Foreign Policy 1870–1914. Archived from the original on March 19, 2017.

- Bury, J.P.T (1968). "Diplomatic History 1900–1912". In Mowat, C. L. (ed.). The New Cambridge Modern History. Vol. XII: The Shifting Balance of World Forces 1898-1945 (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 112–139. ISBN 978-0-521-04551-3.

- Clark, Christopher (March 19, 2013). The Sleepwalkers: How Europe Went to War in 1914. HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0-061-14665-7.

- Clark. "Sleepwalkers". YouTube.

- Engelstein, Laura (2018). Russia in Flames: War, Revolution, Civil War, 1914-1921. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-199-79421-8.

- Fay, Sidney B. (1930). The Origins of the World War. Vol. I, II (2nd ed.).

- Fromkin, David (2004). Europe's Last Summer: Who Started the Great War in 1914?. Knopf. ISBN 978-0-375-41156-4.

- Fuller, William C. (October 1, 1998). Strategy and Power in Russia 1600–1914. Free Press. ISBN 978-0-684-86382-5.

- Geyer, Dietrich (1987). Russian Imperialism: The Interaction of Domestic and Foreign Policy, 1860–1914. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-10545-2.

- Hamilton, Richard F.; Herwig, Holger H. (2004). Decisions for war, 1914–1917. pp. 121–122. doi:10.1017/CBO9780511804854. ISBN 978-0-511-80485-4.

- Hewitson, Mark (2004). Germany and the Causes of the First World War. Berg Publishers. ISBN 978-1-859-73870-2. Archived from the original on April 9, 2017. Retrieved September 2, 2018.

- Herweg, Holger H.; Heyman, Neil (1982). Biographical Dictionary of World War I. Bloomsbury Academic. ISBN 978-0-313-21356-4.

- Jelavich, Barbara (1974). St. Petersburg and Moscow: Tsarist and Soviet Foreign Policy, 1814–1974. ISBN 978-0-253-35050-3.

- Jelavich, Barbara (2004). Russia's Balkan Entanglements, 1806–1914. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-52250-2.

- Joll, James; Martel, Gordon (2013). The Origins of the First World War (3rd ed.). Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-1-317-87535-2.

- Kennan, George Frost (1984). The Fateful Alliance: France, Russia, and the Coming of the First World War. Pantheon Books. ISBN 978-0-394-53494-7.

- Kennedy, Paul M., ed. (1979). The War Plans of the Great Powers: 1880-1914. Routledge. ISBN 9781317702511.

- Lieven, Dominic (2002). Empire: The Russian empire and its rivals. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-09726-9.

- Lieven, D.C.B (1983). Russia and the Origins of the First World War. Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-333-28369-1.

- Lincoln, W. Bruce (1983). In War's Dark Shadow: The Russians Before the Great War. Dial Press. pp. 399–444. ISBN 978-0-385-27409-8.

- Lincoln, W. Bruce (1986). Passage Through Armageddon: The Russians in War and Revolution, 1914-1918. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-671-55709-6.

- McMeekin, Sean (2011). The Russian Origins of the First World War. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-06320-4.

- McMeekin, Sean (April 29, 2014). July 1914: Countdown to War. Basic Books. ISBN 978-0-465-06074-0.

- MacMillan, Margaret (2013). The War That Ended Peace: The Road to 1914. Random House. ISBN 978-0-812-99470-4.

- Menning, Bruce (2009). "War planning and initial operations in the Russian context". In Hamilton, Richard F.; Herwig, Holger (eds.). War Planning, 1914. pp. 120–126. ISBN 978-0-511-64237-1.

- Otte, T. G. (2015). July Crisis: The World's Descent into War, Summer 1914. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-69527-6.

- Pipes, Richard (2011). The Russian Revolution. Knopf Doubleday. ISBN 978-0-307-78857-3.

- Rich, Norman (1992). Great Power Diplomacy: 1814-1914. McGraw Hill. ISBN 978-0-070-52254-1.

- Ritter, Gerhard (1970). The Sword and the Scepter. Vol. 2: The European Powers and the Wilhelminian Empire 1890-1914. Miami University Press. pp. 77–89. ISBN 978-0-870-24128-4.

- Schmitt, Bernadotte E (1930). The coming of the war, 1914. Volume I Volume II

- Scott, Jonathan French (1927). "The psychotic explosion in Russian". Five Weeks: The Surge of Public Opinion on the Eve of the Great War. pp. 154–79. Archived from the original on July 21, 2019. Retrieved September 1, 2018.

- Seton-Watson, Hugh (1967). The Russian Empire 1801–1917. Clarendon Press. pp. 677–697. ISBN 978-0-198-22103-6.

- Soroka, Marina (2016). Britain, Russia and the Road to the First World War: The Fateful Embassy of Count Aleksandr Benckendorff (1903–16). ISBN 978-1-138-26120-4.

- Spring, D.W. (2001). "Russia and the Coming of War". In Evans, R. J. W. (ed.). Coming of the First World War. Oxford University Press. pp. 57–86. ISBN 978-0-198-22899-8.

- Stevenson, David (1988). The First World War and International Politics. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-198-20281-3.

- Stowell, Ellery Cory (1915). The Diplomacy of the War of 1914: The Beginnings of the War (2010 ed.). Kessinger Publishing. ISBN 978-1-165-81956-0.

- Strachan, Hew Francis Anthony (March 13, 2003). The First World War. Vol. 1: To Arms. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-199-26191-8.

- Strachan, Hew Francis Anthony (2004). The First World War. Vol. 3. Viking. ISBN 978-0-670-03295-2.

- Taylor, A.J.P. (1954). The Struggle for Mastery in Europe 1848–1918. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-198-22101-2.

- Tucker, Spencer C., ed. (1996). The European Powers in the First World War: An Encyclopedia. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-0-815-30399-2.

- Vovchenko, Denis (2016). Containing Balkan Nationalism: Imperial Russia and Ottoman Christians, 1856-1914. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-190-27667-6.

- Wildman, Allan K. (1980). The End of the Russian Imperial Army. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-64355-7.

- Zuber, Terence (2002). Inventing the Schlieffen Plan: German War Planning, 1871-1914. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-199-25016-5.

Journals

- Dennis, Alfred L.P. (December 1922). "The Freedom of the Straits". The North American Review. 216 (805): 721–734. JSTOR 25112888.

- Frary, Lucien J. (February 2012). "Review of McMeekin, Sean, The Russian Origins of the First World War". H-Russia, H-Net Reviews.

- Gatrell, Peter (2015). "Tsarist Russia at War: The View from Above, 1914–February 1917". Journal of Modern History. 87 (3): 668–700. doi:10.1086/682414. JSTOR 10.1086/682414. S2CID 146814733.

- Keithly, David M. (1987). "Did Russia Also Have War Aims in 1914?". East European Quarterly. 21 (2): 137+.

- Levy, Jack S.; Mulligan, William (2017). "Shifting power, preventive logic, and the response of the target: Germany, Russia, and the First World War" (PDF). Journal of Strategic Studies. 40 (5): 731–769. doi:10.1080/01402390.2016.1242421. S2CID 157837365.

- Marshall, Alex (2004). "Russian Military Intelligence, 1905–1917: The Untold Story behind Tsarist Russia in the First World War". War in History. 11 (4): 393–423. doi:10.1191/0968344504wh307oa. JSTOR 26061986. S2CID 159841077.

- Menning, Bruce (2015). "Russian Military Intelligence, July 1914: What St. Petersburg Perceived and Why it Mattered". Historian. 77 (2): 213–268. doi:10.1111/hisn.12065. S2CID 142907210.

- Neumann, Iver B. (2008). "Russia as a great power, 1815–2007". Journal of International Relations and Development. 11 (2): 128–151. doi:10.1057/jird.2008.7. S2CID 143792013.

- Neilson, Keith (1985). "Watching the 'steamroller': British observers and the Russian Army before 1914". Journal of Strategic Studies. 8 (2): 199–217. doi:10.1080/01402398508437220.

- Olson, Gust; Miller, Aleksei I. (2004). "Between Local and Inter-Imperial: Russian Imperial History in Search of Scope and Paradigm". Kritika: Explorations in Russian and Eurasian History. 5 (1): 7–26. doi:10.1353/kri.2004.0016. S2CID 143042028.

- Renzi, William A. (1983). "Who Composed "Sazonov Thirteen Points"? A Re-Examination of Russia's War Aims of 1914". American Historical Review. 88 (2): 347–357. doi:10.2307/1865407. JSTOR 1865407.

- Sanborn, Josh (2000). "The mobilization of 1914 and the question of the Russian nation: A reexamination" (PDF). Slavic Review. 59 (2): 267–289. doi:10.2307/2697051. JSTOR 2697051. S2CID 153911953.

- Trachtenberg, Marc (1991). "The Meaning of Mobilization in 1914". International Security. 15 (3): 120–150. doi:10.2307/2538909. JSTOR 2538909. S2CID 155009450.

- Williamson Jr., Samuel R. (2011). "German Perceptions of the Triple Entente after 1911: Their Mounting Apprehensions Reconsidered". Foreign Policy Analysis. 7 (2): 205–214.

- Wohlforth, William C. (April 1987). "The Perception of Power: Russia in the Pre-1914 Balance". World Politics. 39 (3): 353–81. doi:10.2307/2010224. JSTOR 2010224. S2CID 53333300.

Historiography

- Cornelissen, Christoph; Weinrich, Arndt, eds. (2020). Writing the Great War - The Historiography of World War I from 1918 to the Present. Berghahn Books. ISBN 9781789204544.

- Horne, John (2012). A Companion to World War I.

- Kramer, Alan (February 2014). "Recent Historiography of the First World War (Part I)". Journal of Modern European History. Sage Publications. 12 (1): 5–28. doi:10.17104/1611-8944_2014_1_5. S2CID 202927667.

- Kramer, Alan (May 2014). "Recent Historiography of the First World War (Part II)". Journal of Modern European History. Sage Publications. 12 (2): 155–174. doi:10.17104/1611-8944_2014_2_155. S2CID 146860980.

- Mombauer, Annika (2015). "Guilt or Responsibility? The Hundred-Year Debate on the Origins of World War I". Central European History. 48 (4): 541–564. doi:10.1017/S0008938915001144. S2CID 151653269.

- Mulligan, William (2014). "The Trial Continues: New Directions in the Study of the Origins of the First World War". English Historical Review. 129 (538): 639–666. doi:10.1093/ehr/ceu139.

- Winter, Jay; Prost, Antoine, eds. (2005). The Great War in History: Debates and Controversies, 1914 to the Present.

Primary sources

- Gooch, G.P. (1928). Recent revelations of European diplomacy. Longmans, Green and Co. pp. 269–330.

- Major 1914 documents from BYU online

- United States. War Dept. General Staff (1916). Strength and organization of the armies of France, Germany, Austria, Russia, England, Italy, Mexico and Japan (showing conditions in July 1914). Washington, Govt. print. off.