|

|---|

| Periods |

|

| Constitution |

| Political institutions |

| Assemblies |

| Ordinary magistrates |

| Extraordinary magistrates |

| Public law |

| Senatus consultum ultimum |

| Titles and honours |

The Roman Assemblies were institutions in ancient Rome. They functioned as the machinery of the Roman legislative branch, and thus (theoretically at least) passed all legislation. Since the assemblies operated on the basis of a direct democracy, ordinary citizens, and not elected representatives, would cast all ballots. The assemblies were subject to strong checks on their power by the executive branch and by the Roman Senate. Laws were passed (and magistrates elected) by Curia (in the Curiate Assembly), Tribes (in the Tribal Assembly), and century (in the Centuriate Assembly).

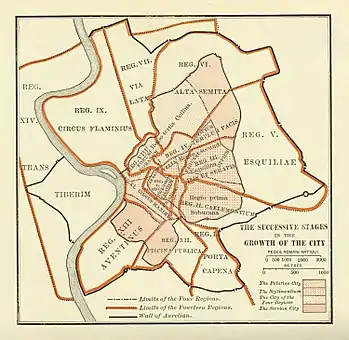

When the city of Rome was founded (traditionally dated at 753 BC), a senate and an assembly, the Curiate Assembly, were both created. The Curiate Assembly was the principal legislative assembly during the era of the Roman Kingdom. While its primary purpose was to elect new kings, it also possessed rudimentary legislative powers. Shortly after the founding of the Roman Republic (traditionally dated to 509 BC), the principal legislative authority shifted to two new assemblies, the Tribal Assembly ("Citizen's Assembly") and the Centuriate Assembly.

Under the empire, the powers that had been held by the assemblies were transferred to the senate. While the assemblies eventually lost their last semblance of political power, citizens continued to gather into them for organizational purposes. Eventually, however, the assemblies were abandoned.

Assemblies of the Roman Kingdom

The Legislative Assemblies of the Roman Kingdom were political institutions in the ancient Roman Kingdom. While one assembly, the Curiate Assembly, had some legislative powers,[1] these powers involved nothing more than a right to symbolically ratify decrees issued by the Roman King.[2] The functions of the other assembly, the Calculate Assembly, were purely religious.

During the years of the kingdom, the People of Rome were organized on the basis of units called curia.[1] All of the People of Rome were divided amongst a total of thirty curiae.[1] These curiae were the basic units of division in the two popular assemblies.[3] The members in each curia would vote, and the majority in each curia would determine how that curia voted before the assembly. Thus, a majority of the curiae (sixteen out of the thirty total curiae) were needed during any vote before either the Curiate Assembly or the Calculate Assembly. They functioned as the Roman legislative branch.

The king presided over the assembly, and submitted decrees to it for ratification.[2] After a king died, the Interrex selected a candidate to replace the king.[4] After the nominee received the approval of the Roman Senate, the Interrex held the formal election before the Curiate Assembly. After the Curiate Assembly elected the new king, and the senate ratified that election, the Interrex then presided over the assembly as it voted on the law which granted the king his legal powers (the lex curiata de imperio).[4] On the calends (the first day of the month), and the nones (around the fifth day of the month), this assembly met to hear announcements.[2] Appeals heard by this assembly often had to deal with questions concerning Roman family law.[5] During two fixed days in the spring, the assembly was to always meet to witness wills and adoptions.[2] The assembly also had jurisdiction over the admission of new families to a curia, the transfer of families between two curiae, and the transfer of individuals from plebeian (commoner) to patrician (aristocratic) status (or vice versa).[2]

Assemblies of the Roman Republic

The Legislative Assemblies of the Roman Republic were political institutions in the ancient Roman Republic. There were two types of Roman assembly. The first was the comitia,[6] which was an assembly of Roman citizens.[7] Here, Roman citizens gathered to enact laws, elect magistrates, and try judicial cases. The second type of assembly was the council (concilium), which was an assembly of a specific group of citizens.[7] For example, the "Plebeian Council" was an assembly where Plebeians gathered to elect Plebeian magistrates, pass laws that applied only to Plebeians, and try judicial cases concerning Plebeians.[8] A convention (conventio), in contrast, was an unofficial forum for communication, where citizens gathered to debate bills, campaign for office, and decide judicial cases.[6] The voters first assembled into conventions to deliberate, and then they assembled into committees or councils to actually vote.[9] In addition to the curiae (familial groupings), Roman citizens were also organized into centuries (for military purposes) and tribes (for civil purposes). Each gathered into an assembly for legislative, electoral, and judicial purposes. The Centuriate Assembly was the assembly of the Centuries, while the Tribal Assembly was the assembly of the Tribes. Only a block of voters (Century, Tribe or Curia), and not the individual electors, cast the formal vote (one vote per block) before the assembly.[10] The majority of votes in any Century, Tribe, or Curia decided how that Century, Tribe, or Curia voted.

The Centuriate Assembly was divided into 193 (later 373) Centuries, with each Century belonging to one of three classes: the officer class, the infantry, and the unarmed adjuncts.[11][12] During a vote, the Centuries voted, one at a time, by order of seniority. The president of the Centuriate Assembly was usually a Roman Consul (the chief magistrate of the republic).[13] Only the Centuriate Assembly could elect Consuls, Praetors and Censors, declare war,[14] and ratify the results of a census.[15] While it had the power to pass ordinary laws (leges), it rarely did so.

The organization of the Tribal Assembly was much simpler than was that of the Centuriate Assembly, in contrast, since its organization was based on only thirty-five Tribes. The Tribes were not ethnic or kinship groups, but rather geographical divisions (similar to modern U.S. Congressional districts or Commonwealth Parliamentary constituencies).[16] The president of the Tribal Assembly was usually a Consul,[13] and under his presidency, the assembly elected Quaestors, Curule Aediles, and Military Tribunes.[17] While it had the power to pass ordinary laws (leges), it rarely did so. The assembly known as the Plebeian Council was identical to the Tribal Assembly with one key exception: only plebeians (the commoners) had the power to vote before it. Members of the aristocratic patrician class were excluded from this assembly. In contrast, both classes were entitled to a vote in the Tribal Assembly. Under the presidency of a Plebeian Tribune (the chief representative of the people), the Plebeian Council elected Plebeian Tribunes and Plebeian Aediles (the Plebeian Tribune's assistant), enacted laws called plebiscites, and presided over judicial cases involving Plebeians. Originally, laws passed by the Plebeian Council only applied to Plebeians.[18] However, by 287 BC, laws passed by the Plebeian Council had acquired the full force of law, and from that point on, most legislation came from the council.

Assemblies of the Roman Empire

The legislative assemblies of the Roman Empire were political institutions in the ancient Roman Empire. During the reign of the second Roman Emperor, Tiberius, the powers that had been held by the Roman assemblies were transferred to the senate. After the founding of the Roman Empire, the People of Rome continued to organize by Centuries and by Tribes, but by this point, these divisions had lost most of their relevance.[19]

While the machinery of the Centuriate Assembly continued to exist well into the life of the empire,[19] the assembly lost all of its practical relevance. Under the empire, all gatherings of the Centuriate Assembly were in the form of an unsorted convention. Legislation was never submitted to the imperial Centuriate Assembly, and the one major legislative power that this assembly had held under the republic, the right to declare war, was now held exclusively by the emperor.[19] All judicial powers that had been held by the republican Centuriate Assembly were transferred to independent jury courts, and under the emperor Tiberius, all of its former electoral powers were transferred to the senate.[19] After it had lost all of these powers, it had no remaining authority. Its only remaining function was, after the senate had 'elected' the magistrates, to hear the renuntiatio,[19] which had no legal purpose, but instead was a ceremony in which the results of the election were read to the electors. This allowed the emperor to claim that the magistrates had been "elected" by a sovereign people.

In the early empire, the tribal divisions of citizens and freedmen continued, but the only political purpose of the tribal divisions was such that they better enabled the senate to maintain a list of citizens.[19] Tribal divisions also simplified the process by which grain was distributed.[19] Eventually, most freedmen belonged to one of the four urban Tribes, while most freemen belonged to one of the thirty-one rural Tribes.[19] Under the emperor Tiberius, the electoral powers of the Tribal Assembly were transferred to the senate. Each year, after the senate had elected the annual magistrates, the Tribal Assembly also heard the renuntiatio.[19] Any legislation that the emperor submitted to the assemblies for ratification were submitted to the Tribal Assembly.[19] The assembly ratified imperial decrees, starting with the emperor Augustus, and continuing until the emperor Domitian. The ratification of legislation by the assembly, however, had no legal importance as the emperor could make any decree into law, even without the acquiescence of the assemblies. Thus, under the empire, the chief executive again became the chief lawgiver, which was a power he had not held since the days of the early republic.[19] The Plebeian Council also survived the fall of the republic,[19] and it also lost its legislative, judicial and electoral powers to the senate. By virtue of his tribunician powers, the emperor had absolute control over the council.[19]

See also

Notes

References

- Abbott, Frank Frost (1901). A History and Description of Roman Political Institutions. Elibron Classics (ISBN 0-543-92749-0).

- Byrd, Robert (1995). The Senate of the Roman Republic. U.S. Government Printing Office, Senate Document 103–23.

- Cicero, Marcus Tullius (1841). The Political Works of Marcus Tullius Cicero: Comprising his Treatise on the Commonwealth; and his Treatise on the Laws. Translated from the original, with Dissertations and Notes in Two Volumes. By Francis Barham, Esq. London: Edmund Spettigue. Vol. 1.

- Lintott, Andrew (1999). The Constitution of the Roman Republic. Oxford University Press (ISBN 0-19-926108-3).

- Polybius (1823). The General History of Polybius: Translated from the Greek. By James Hampton. Oxford: Printed by W. Baxter. Fifth Edition, Vol 2.

- Taylor, Lily Ross (1966). Roman Voting Assemblies: From the Hannibalic War to the Dictatorship of Caesar. The University of Michigan Press (ISBN 0-472-08125-X).

Further reading

- Ihne, Wilhelm. Researches Into the History of the Roman Constitution. William Pickering. 1853.

- Johnston, Harold Whetstone. Orations and Letters of Cicero: With Historical Introduction, An Outline of the Roman Constitution, Notes, Vocabulary and Index. Scott, Foresman and Company. 1891.

- Mommsen, Theodor. Roman Constitutional Law. 1871–1888

- Tighe, Ambrose. The Development of the Roman Constitution. D. Apple & Co. 1886.

- Von Fritz, Kurt. The Theory of the Mixed Constitution in Antiquity. Columbia University Press, New York. 1975.

- The Histories by Polybius

- Cambridge Ancient History, Volumes 9–13.

- A. Cameron, The Later Roman Empire, (Fontana Press, 1993).

- M. Crawford, The Roman Republic, (Fontana Press, 1978).

- E. S. Gruen, The Last Generation of the Roman Republic (U California Press, 1974)

- F. Millar, The Emperor in the Roman World, (Duckworth, 1977, 1992).

- A. Lintott, The Constitution of the Roman Republic (Oxford University Press, 1999)

Primary sources

Secondary source material

- Considerations on the Causes of the Greatness of the Romans and their Decline, by Montesquieu

- The Roman Constitution to the Time of Cicero

- What a Terrorist Incident in Ancient Rome Can Teach Us

- An extensive collection of digital books and articles on Roman Law and History, in various languages. By professor Luiz Gustavo Kaercher

External links

| Library resources about Roman assemblies |