| Metroid | |

|---|---|

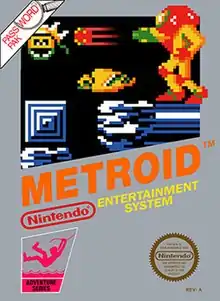

North American packaging artwork | |

| Developer(s) | |

| Publisher(s) | Nintendo |

| Director(s) | Satoru Okada |

| Producer(s) | Gunpei Yokoi |

| Artist(s) |

|

| Writer(s) | Makoto Kano |

| Composer(s) | Hirokazu Tanaka |

| Series | Metroid |

| Platform(s) | |

| Release | |

| Genre(s) | Action-adventure |

| Mode(s) | Single-player |

| Arcade system | PlayChoice-10 |

Metroid[lower-alpha 1] is an action-adventure game developed and published by Nintendo. The first installment in the Metroid series, it was originally released in Japan for the Family Computer Disk System in August 1986. North America received a release in August 1987 on the Nintendo Entertainment System in the Game Pak ROM cartridge format, with the European release following in January 1988. Set on the planet Zebes, the story follows Samus Aran as she attempts to retrieve the parasitic Metroid organisms that were stolen by Space Pirates, who plan to replicate the Metroids by exposing them to beta rays and then use them as biological weapons to destroy Samus and all who oppose them.

The game was developed by Nintendo Research & Development 1 (Nintendo R&D1) and Intelligent Systems. It was produced by Gunpei Yokoi, directed by Satoru Okada and Masao Yamamoto, and scored by Hirokazu Tanaka. It pioneered the Metroidvania genre, focusing on exploration and searching for power-ups used to reach previously inaccessible areas. Its varied endings for fast completion times made it an early popular title for speedrunning. It was also lauded for being one of the first video games to showcase a female protagonist.

Metroid was both a critical and commercial success. Reviewers praised its graphics, soundtrack, and tight controls. Nintendo Power ranked it 11th on their list of the best games for a Nintendo console. On Top 100 Games lists, it was ranked 7th by Game Informer and 69th by Electronic Gaming Monthly. The game has been rereleased multiple times onto other Nintendo systems, such as the Game Boy Advance in 2004, the Wii, Wii U and 3DS via the Virtual Console service, and the Nintendo Switch via its online service. An enhanced remake of Metroid featuring updated visuals and gameplay, Metroid: Zero Mission, was released for the Game Boy Advance in 2004.

Gameplay

Metroid is an action-adventure game in which the player controls Samus Aran in sprite-rendered two-dimensional landscapes. The game takes place on the planet Zebes, a large, open-ended world with areas connected by doors and elevators. The player controls Samus as she travels through the planet's caverns and hunts Space Pirates. She begins with a weak power beam as her only weapon, and with only the ability to jump. The player explores more areas and collects power-ups that grant Samus special abilities and enhance her armor and weaponry, allowing her to enter areas that were previously inaccessible. Among the power-ups that are included in the game are the Morph Ball, which allows Samus to curl into a ball to roll into tunnels; the Bomb, which can only be used while in ball form and can open hidden floor/wall paths; and the Screw Attack, a somersaulting move that destroys enemies in its path.[1][2]

In addition to common enemies, Samus encounters two bosses, Kraid and Ridley, whom she must defeat in order to progress. Ordinary enemies typically yield additional energy or ammunition when destroyed, and the player can increase Samus's carrying capacities by finding storage tanks and defeating bosses. Once Kraid and Ridley have both been defeated, the player can shoot their statues to open the path to the final area and confront the Mother Brain.[1][2]

Plot

| Metroid | |||

| Story chronology | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Main series in bold, remakes in parentheses | |||

|

|

|||

| [3][4] | |||

In the year 20X5, the Space Pirates attack a Galactic Federation-owned space research vessel and seize samples of Metroid creatures—the parasitic lifeforms discovered on the planet SR388. Dangerous floating organisms, the Metroids can latch on to any organism and drain its life energy to kill it. The Space Pirates plan to replicate Metroids by exposing them to beta rays and then using them as biological weapons to destroy all living beings that oppose them. While searching for the stolen Metroids, the Galactic Federation locates the Space Pirates' base of operations on the planet Zebes. The Federation assaults the planet, but the Pirates resist, forcing the Federation to retreat.[1][2]

As a last resort, the Federation decides to send a lone bounty hunter to penetrate the Pirates' base and destroy Mother Brain, the biomechanical life-form that controls the Space Pirates' fortress and its defenses. Considered the greatest of all bounty hunters, Samus Aran is chosen for the mission.[1] Samus lands her gunship on the surface of Zebes and explores the planet, traveling through the planet's caverns, finding upgrades like missiles, energy tanks, the morph ball, bombs, screw attack (lightning ball), and ice beam, and uses these weapons to dispatch the alien creatures who get in her way. She comes across Kraid, an ally of the Space Pirates, and Ridley, the Space Pirates' commander, and defeats them both. Eventually, Samus kills the Metroids, and finds and destroys Mother Brain.[2] A timed bomb goes off to destroy the lair and Samus is able to escape before it explodes.[5]

Development

_cropped.jpg.webp)

After Nintendo's release of commercially successful platforming games in the 1980s, including Donkey Kong (1981), Ice Climber (1985), Super Mario Bros. (1985), and the critically acclaimed adventure game The Legend of Zelda (1986), the company began work on an action game.[6] The word "Metroid" is a portmanteau of the words "metro" and "android".[7][8] It was co-developed by Nintendo's Research and Development 1 division and Intelligent Systems, and produced by Gunpei Yokoi.[9][10][8] Metroid was directed by Satoru Okada and Masao Yamamoto (credited as "Yamamoto"), and featured music written by Hirokazu Tanaka (credited as "Hip Tanaka").[8][11] The scenario was created by Makoto Kano (credited with his last name), and character design was done by Hiroji Kiyotake (credited with his last name), Hirofumi Matsuoka (credited as "New Matsuoka"), and Yoshio Sakamoto (credited as "Shikamoto").[8] The character design for Samus Aran was created by Kiyotake.[12][13]

The production was described as a "very free working environment" by Tanaka, who stated that, though being the composer, he also gave input for the graphics and helped name areas. Partway through development, one of the developers asked the others, "Hey, wouldn't that be kind of cool if it turned out that this person inside the suit was a woman?" This idea was incorporated into the game, though the English-language instruction manual for the game uses only the pronoun "he" in reference to Samus.[14] Ridley Scott's 1979 horror film Alien was described by Sakamoto as a "huge influence" after the game's world had been created. The development staff was affected by the work of the film's creature designer H. R. Giger, and found his creations to be fitting for the theme.[15] Still, there were problems that threatened timely progress and eventually led Sakamoto to be "forcefully asked to participate" by his superiors, hoping his previous experience could help the team. Sakamoto stated he figured out a way to bypass the limited resources and time to leverage existing game media assets "to create variation and an exciting experience".[16]

Nintendo attempted to distinguish Metroid from other games by making it a nonlinear adventure-based game, in which exploration was a crucial part of the experience. The game often requires that the player retrace steps to progress, forcing the player to scroll the screen in all directions, as with most contemporary games. Metroid is considered one of the first video games to impress a feeling of desperation and solitude on the player. Following The Legend of Zelda, Metroid helped pioneer the idea of acquiring tools to strengthen characters and help progress through the game. Until then, most ability-enhancing power-ups like the Power Shot in Gauntlet (1985) and the Starman in Super Mario Bros. offer only temporary boosts to characters, and they are not required to complete the game. In Metroid, however, items are permanent fixtures that lasted until the end. In particular, missiles and the ice beam are required to finish the game.[6]

After defeating Mother Brain, the game presents one of five ending screens based on the time to completion. Metroid is one of the first games to contain multiple endings. In the third, fourth, and fifth endings, Samus Aran appears without her suit, and for the first time, reveals herself to be a woman. In Japan, the Disk Card media used by the Famicom Disk System allows players up to three different saved game slots in Metroid, similar to The Legend of Zelda in the West. Use of an internal battery to manage files was not fully realized in time for Metroid's international release. The Western versions of Metroid use a password system that was new to the industry at the time, in which players write down a 24-letter code and re-enter it into the game when they wish to continue a previous session. Codes also allow for cheats, such as "NARPAS SWORD"[6] and "JUSTIN BAILEY".

Music

Tanaka said he wanted to make a score that made players feel like they were encountering a "living organism" and had no distinction between music and sound effects. The only time a melodic theme is heard is when Mother Brain is defeated in order to give the victorious player catharsis. During the rest of the game, the melodies are more minimalistic, because Tanaka wanted the soundtrack to be the opposite of the "hummable" pop tunes found in other games at that time.[17]

Release

Officially defined as a scrolling shooter video game, Metroid was released by Nintendo for the Famicom Disk System in Japan on August 6, 1986.[18][6] An arcade version of the game was released in 1987 for Nintendo's PlayChoice-10 system.[19] It was released on the Nintendo Entertainment System a year later on August 15, 1987, in North America, and on January 15, 1988, in Europe.[18][20]

Emulation

The game was re-released several times via emulation. Linking the Game Boy Advance game Metroid Fusion (2002) with the GameCube's Metroid Prime (2002) using a link cable unlocks the full version of Metroid on the GameCube.[21] The game is unlocked as a bonus upon completion of Metroid: Zero Mission (2004).[22] A stand-alone version of Metroid for the Game Boy Advance, part of the Classic NES Series collection, was released in Japan on August 10, 2004, in North America on October 25, and in Europe on January 7, 2005.[23] The game arrived on the Wii's Virtual Console in Europe and North America in 2007, and in Japan on March 4, 2008.[24] Metroid was released for the Nintendo 3DS Virtual Console on March 1, 2012.[25]

At E3 2010, Nintendo featured Metroid among NES and SNES games in a tech demo called Classic Games, to be released for the Nintendo 3DS. Nintendo of America president Reggie Fils-Aimé said "not to think of them as remakes". Miyamoto said that these classics might be using "new features in the games that would take advantage of the 3DS's capabilities".[26] This was released as part of 3D Classics series which does not include Metroid.

Remake

The game was reimagined as Metroid: Zero Mission with a more developed backstory, enhanced graphics, and the same general game layout.

Reception

Metroid was a commercial success, reported to be "famous" and "very popular" by 1989.[27][28] As of 2004, 2.73 million units of Metroid have been sold worldwide.[29]

Critics

| Aggregator | Score | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| GBA | NES | Wii | |

| GameRankings | 62%[30] | 63% (retrospective)[31] | N/A |

| Publication | Score | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| GBA | NES | Wii | |

| AllGame | |||

| Computer and Video Games | N/A | 80%[27] | N/A |

| Famitsu | N/A | N/A | |

| Game Players | N/A | Positive[28] | N/A |

| GameSpot | N/A | N/A | 5.5/10[36] |

| IGN | N/A | N/A | 8/10 [37] |

| Nintendo Power | N/A | 17.5/20[38] | N/A |

Metroid received positive reviews from critics upon release. Famicom Tsūshin (Famitsu) magazine rated it five out of five stars in 1989.[35] Computer and Video Games said it was a "tough" platform arcade adventure with a "very handy" password system and recommended it to "avid" arcade adventurers.[27] Game Players praised its "fast-paced" gameplay.[28] In Nintendo Power's NES retrospective in 1990, Metroid was rated 5/5 for Graphic and Sound, 4.5/5 for Play Control, 5/5 for Challenge, and 5/5 for Theme Fun.[38]

In 2006, Nintendo Power ranked Metroid as the 11th-best game on its list of the Top 200 Games on a Nintendo video game console.[39] Two years later, the magazine named Metroid the fifth-best game for the Nintendo Entertainment System in its Best of the Best feature, describing it as a combination of Super Mario Bros.'s platforming and The Legend of Zelda's exploration and character upgrades.[40] The game was ranked 44th on Electronic Gaming Monthly's original 100 best games of all time in 1997,[41] dropped to 69th in 2001,[42] but was ranked 11th on its "Greatest 200 Videogames of Their Time" in 2006, which ranks games on their impact at the time (whereas EGM's earlier lists rank games based on lasting appeal, with no consideration given to innovation or influence).[43] Game Informer ranked it 6th best game of all time in 2001[44] and 7th in 2009, saying that it "started the concept of open exploration in games".[45] In 2004, Metroid was inducted into GameSpot's list of the greatest games of all time.[46] GamesRadar ranked it the fifth best NES game ever made. The staff said that it had aged after the release of Super Metroid but was "fantastic for its time".[47] Metroid's ranking of multiple endings entices players to race the game, or speedrunning.[6] Entertainment Weekly called it the #18 greatest game available in 1991, saying: "The visuals are simplistic, but few games make you think as much as the five-year-old Metroid. Try not to consult Nintendo's hint book, which provides detailed maps of the terrain your hero has to navigate in order to complete his mission".[48]

In a retrospective focusing on the entire Metroid series, GameTrailers remarked on the original game's legacy and its effect on the video game industry. They noted that Metroid launched the series with its ever-popular search and discovery gameplay. The website said that the combination of detailed sprites, original map designs, and an intimidating musical score "generated an unparalleled ambience and atmosphere that trapped the viewer in an almost claustrophobic state". They noted that the Morph Ball, first introduced in Metroid, "slammed an undeniable stamp of coolness on the whole experience and the franchise", and they enjoyed the end segment after defeating Mother Brain, describing the race to escape the planet Zebes as a "twist few saw coming". They said the game brought "explosive action" to the NES and a newfound respect for female protagonists.[6] Noting that Metroid is not the first game to offer an open world, or the first side-view platformer exploration game, or the first game to allow players to reach new areas using newly acquired items, Gamasutra praised Metroid for being perhaps the first video game to "take these different elements and rigorously mold them into a game-ruling structure".[49]

Reviewing the original NES game, AllGame awarded Metroid with the highest rating of five stars.[33] The review praised the game above Metroid II: Return of Samus and Super Metroid, stating that "Metroid's not just a classic because of its astounding graphics, cinematic sound effects, accurate control, and fresh gameplay, but also because of its staying power".[33] Reviewing the Classic NES Series version of the game, GameSpot noted that eighteen years after its initial release, Metroid "just doesn't measure up to today's action adventure standards", giving the game a rating of 5.2 out of 10, for "mediocre".[50] For the Wii Virtual Console version, IGN commented that the game's presentation, graphics, and sound were basic. However, they were still pleased with Metroid's "impressive" gameplay, rating the game 8.0 out of 10, for "great", and giving it an Editor's Choice award. The review stated that the game was "still impressive in scope" and that the price was "a deal for this adventure" while criticizing the number of times it has been re-released and noting that it takes "patience" to get past the high initial difficulty curve.[51] In GameSpot's review of the Virtual Console version, they criticized its "frustrating room layouts" and "constantly flickering graphics". In particular, the website was disappointed that Nintendo did not make any changes to the game, specifically criticizing the lack of a save feature.[52]

Metroid's gameplay, focusing on exploration and searching for power-ups to reach new areas, influenced other series, mostly the Castlevania series.[53] The revelation of Samus being a woman was lauded as innovative, and GameTrailers remarked that this "blew the norm of women in pieces, at a time when female video game characters were forced into the role of dutiful queen or kidnapped princess, missile-blasting the way for other characters like Chun-Li [from the Street Fighter series] and Lara Croft [from the Tomb Raider series]".[6]

Music

In his book Maestro Mario: How Nintendo Transformed Videogame Music into an Art, videogame scholar Andrew Schartmann notes the possible influence of Jerry Goldsmith's Alien score on Tanaka's music—a hypothesis supported by Sakamoto's acknowledgement of Alien's influence on the game's development. He also noted that the game emphasises on the silence to create a claustrophobic atmosphere.[54] Schartmann further argues that Tanaka's emphasis on silence was revolutionary to videogame composition:

Tanaka's greatest contribution to game music comes, paradoxically, in the form of silence. He was arguably the first videogame composer to emphasize the absence of sound in his music. Tanaka's score is an embodiment of isolation and atmospheric effect—one that penetrates deeply into the emotions.

— Andrew Schartmann, Maestro Mario: How Nintendo Transformed Videogame Music into an Art, Thought Catalog (2013)[55]

This view is echoed by GameSpot's History of Metroid, which notes how the "[game's music] superbly evoked the proper feelings of solitude and loneliness one would expect while infiltrating a hostile alien planet alone".[2]

Notes

References

- 1 2 3 4 Metroid Instruction Booklet (PDF). USA: Nintendo of America. 1989. NES-MT-USA-1. Archived (PDF) from the original on June 23, 2017. Retrieved July 4, 2017.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Shoemaker, Brad. "The History of Metroid". GameSpot. p. Metroid. Archived from the original on October 3, 2013. Retrieved April 8, 2014.

- ↑ Quick, William Antonio (June 23, 2021). "Every Metroid Game In Chronological Order". TheGamer. Retrieved February 13, 2023.

- ↑ Parish, Jeremy (August 5, 2015). "Page 2 | "I was quite surprised by the backlash": Kensuke Tanabe on Metroid Prime Federation Force". VG247. Retrieved February 15, 2023.

First off, [Yoshio] Sakamoto is behind the main series, taking care of all of that, the timeline. I'm in charge of the Prime series. I had the conversation with him to decide where exactly would be a good spot for me to stick the Prime universe into that whole timeline and the best place would be between Metroid II and Super Metroid. As you know, there are multiple titles in the Metroid Prime series, but everything takes place in that very specific point. Metroid Series go down the line, but with the Prime Universe, we have to stretch sideways to expand it as much as we can in that specific spot.

- ↑ Nintendo R&D1 (August 15, 1987). Metroid (Nintendo Entertainment System). Nintendo of America. Level/area: Tourian.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 "The Metroid Retrospective – Part 1". GameTrailers. June 6, 2006. Archived from the original on April 10, 2014. Retrieved April 8, 2014.

- ↑ "Episode 10". GameCenter CX. 2003. Fuji TV.

- 1 2 3 4 Nintendo R&D1 (August 15, 1987). Metroid. Nintendo of America. Scene: Staff credits.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ↑ 「メトロイド」に託す思い 坂本賀勇インタビュー. ニンテンドウオンラインマガジン(No.56). Nintendo Co., Ltd. March 2003. Archived from the original on March 7, 2010. Retrieved August 22, 2010.

- ↑ Christian Nutt (April 23, 2010). "The Elegance Of Metroid: Yoshio Sakamoto Speaks". Gamasutra. United Business Media. Archived from the original on May 12, 2015. Retrieved August 5, 2010.

- ↑ "Nintendo Online Magazine No. 76 – Nintendo DS 開発者インタビュー" (in Japanese). Nintendo. November 2004. Archived from the original on December 10, 2011. Retrieved June 21, 2011.

- ↑ やればやるほどディスクシステムインタビュー(前編). Nintendo Dream (in Japanese). No. 118. Mainichi Communications. August 6, 2004. pp. 96–103.

- ↑ "Yoshio Sakamoto bio". GDC 2010 Online Press Kit. Nintendo of America, Inc. March 2010. Archived from the original on August 6, 2010. Retrieved August 6, 2010.

- ↑ "Metroid: Zero Mission director roundtable". IGN. January 30, 2004. Archived from the original on March 24, 2008. Retrieved February 20, 2008.

- ↑ "The Making of Super Metroid". Retro Gamer. No. 65. Imagine Publishing. July 2009. p. 60.

- ↑ "Metroid Made New". Game Informer. No. 293. September 2017. p. 61.

- ↑ Tanaka, Hirokazu (September 25, 2002). "Shooting from the Hip: An Interview with Hip Tanaka". Gamasutra (Interview). Interviewed by Brandon, Alex. Archived from the original on March 21, 2008. Retrieved February 19, 2008.

- 1 2 "Iwata Asks: Metroid: Other M – Vol. 1: The Collaboration / Just One Wii Remote". Nintendo of America Inc. July 29, 2010. Archived from the original on July 22, 2011. Retrieved July 3, 2011.

- ↑ "Metroid - Videogame by Nintendo". International Arcade Museum - Killer List of Videogames. Retrieved December 21, 2023.

- ↑ "Metroid Related Games". GameSpot. Archived from the original on June 29, 2013. Retrieved April 18, 2013.

- ↑ Mirabella III, Fran (December 15, 2002). "Metroid Prime Guide: Secrets". IGN. Archived from the original on June 11, 2004. Retrieved February 22, 2009.

- ↑ Metts, Jonathan (February 12, 2004). "Metroid: Zero Mission". Nintendo World Report. Archived from the original on April 28, 2009. Retrieved February 22, 2009.

- ↑ "Classic NES Series: Metroid Release Summary". GameSpot. Archived from the original on May 11, 2006. Retrieved August 27, 2009.

- ↑ "Metroid for Wii: Game Editions". IGN. August 10, 2007. Archived from the original on May 22, 2012. Retrieved December 26, 2008.

- ↑ "Nintendo eShop: Metroid". Nintendo. Archived from the original on May 11, 2012. Retrieved July 5, 2012.

- ↑ Totilo, Stephen (June 18, 2010). "Mega Man 2, Yoshi's Island Among Teased 3DS Sorta-Remakes". Kotaku. Archived from the original on June 21, 2010. Retrieved July 18, 2010.

- 1 2 3 "Complete Games Guide" (PDF). Computer and Video Games (Complete Guide to Consoles): 46–77. October 16, 1989.

- 1 2 3 "100 Guidepost: The Hot 100". Game Players. No. 5. United States: Signal Research. November 1989. pp. 106–11.

- ↑ 2004 CESA Games White Paper. Computer Entertainment Supplier's Association. December 31, 2003. pp. 58–63. ISBN 4-902346-04-4.

- ↑ "Classic NES Series: Metroid for Game Boy Advance". GameRankings. Archived from the original on December 9, 2019.

- ↑ "Metroid for NES". GameRankings. Archived from the original on December 9, 2019.

- ↑ "Metroid [Classic NES Series] - Overview". AllGame. Archived from the original on November 14, 2014. Retrieved August 1, 2021.

- 1 2 3 Norris IV, Benjamin F. "Metroid - Review". Allgame. Archived from the original on November 14, 2014. Retrieved May 5, 2015.

- ↑ "Metroid [Virtual Console] - Overview". AllGame. Archived from the original on November 14, 2014. Retrieved August 1, 2021.

- 1 2 "メトロイド" [Metroid]. ファミコン通信 〜 '89全ソフトカタログ [Famicom Tsūshin: '89 All Software Catalog]. Famicom Tsūshin. Japan: ASCII Corporation. September 15, 1989. p. 49.

- ↑ Provo, Frank. "Metroid Review". GameSpot. Archived from the original on January 24, 2013. Retrieved December 6, 2012.

- ↑ "Metroid Review - IGN". August 14, 2007 – via www.ign.com.

- 1 2 "Pak Source". Nintendo Power. United States: Nintendo of America. January 1990.

- ↑ "NP Top 200". Nintendo Power. No. 200. February 2006. pp. 58–66.

- ↑ "NP Best of the Best". Nintendo Power. No. 231. August 2008. pp. 70–78.

- ↑ "100 Best Games of All Time". Electronic Gaming Monthly. No. 100. Ziff Davis. November 1997. p. 130. Note: Contrary to the title, the intro to the article explicitly states that the list covers console video games only, meaning PC games and arcade games were not eligible.

- ↑ "Top 100 Games of All Time". Electronic Gaming Monthly. Archived from the original on June 19, 2004. Retrieved February 22, 2009.

- ↑ "The Greatest 200 Videogames of Their Time". 1UP.com. Archived from the original on May 19, 2006.

- ↑ "Top 100 Games of All-Time". Game Informer. No. 100. August 2001. p. 34.

- ↑ The Game Informer staff (December 2009). "Game Informer's Top 100 Games Of All Time (Circa Issue 100)". Game Informer. No. 200. pp. 44–79. ISSN 1067-6392. OCLC 27315596. Archived from the original on November 11, 2011. Retrieved July 9, 2010.

- ↑ "The Greatest Games of All Time: Metroid". GameSpot. Archived from the original on October 16, 2007.

- ↑ "Best NES Games of all time". GamesRadar. April 16, 2012. Archived from the original on June 30, 2015. Retrieved December 5, 2013.

- ↑ "Video Games Guide". EW.com.

- ↑ "Game Design Essentials: 20 Open World Games". Gamasutra. Archived from the original on December 21, 2008. Retrieved February 23, 2009.

- ↑ Colayco, Bob (November 3, 2004). "Classic NES Series: Metroid Review". GameSpot. Archived from the original on October 30, 2013. Retrieved February 23, 2009.

- ↑ Thomas, Lucas M. (August 13, 2007). "Metroid Review". IGN. Archived from the original on February 20, 2009. Retrieved February 23, 2009.

- ↑ Provo, Frank (August 27, 2007). "Metroid Review". GameSpot. Archived from the original on December 14, 2011. Retrieved February 23, 2009.

- ↑ Oxford, Nadia (August 7, 2006). "One Girl Against the Galaxy: 20 Years of Metroid and Samus Aran". 1UP.com. Retrieved February 22, 2009.

- ↑ Schartmann, Andrew. Maestro Mario: How Nintendo Transformed Videogame Music into an Art Archived August 23, 2013, at the Wayback Machine. New York: Thought Catalog, 2013.

- ↑ Maestro Mario: How Nintendo Transformed Videogame Music into an Art, Thought Catalog (2013)

Further reading

- Tanaka, Hirokazu (November 22, 2014). Hirokazu Tanaka on Nintendo Game Music, Reggae and Tetris | Red Bull Music Academy (YouTube video: lecture) (in English and Japanese). Tokyo. Event occurs at 51:48. Archived from the original on December 21, 2021. (details the internal reception of the game's music)

External links

- Metroid Archived July 20, 2010, at the Wayback Machine at the Metroid Database