| Mamianqun | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

.jpg.webp) Mamianqun, a traditional Han Chinese skirt, Qing dynasty. | |||||||

| Chinese name | |||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 馬面裙 | ||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 马面裙 | ||||||

| Literal meaning | horse face skirt | ||||||

| |||||||

| English name | |||||||

| English | Horse-face skirt/ paired apron/ apron | ||||||

| Type | Chinese wrap-around, skirt with either pleats or gores |

|---|---|

| Material | Various (including silk) |

| Place of origin | Song dynasty, China |

| Introduced | c. 11th century |

Mamianqun (simplified Chinese: 马面裙; traditional Chinese: 馬面裙; pinyin: mǎmiànqún; lit. 'horse face skirt'), is a type of traditional Chinese skirt. It is also known as mamianzhequn (simplified Chinese: 马面褶裙; traditional Chinese: 馬面褶裙; lit. 'horse-face pleated skirt'), but is sometimes simply referred as 'apron' (Chinese: 围裙; pinyin: wéiqún; lit. 'apron'), a generic term in English to refer to any Chinese-style skirt, or 'paired apron' in English although they are not aprons as defined in the dictionary. The Mamianqun is a type of qun (Chinese: 裙; pinyin: qún; lit. 'skirt') a traditional Chinese skirt worn by the Han Chinese women as a lower garment item in Hanfu[1][2]: 54 [3] and is one of the main representative styles of ancient Chinese-style skirts.[4] It originated in the Song and Liao dynasties and became popular due to its functionality and its aesthetics style.[5] It continued to be worn in the Yuan,[3] Ming, and Qing dynasties where it was a typical style of skirt for women[6] and was favoured for its unique aesthetic style and functionality.[5] Following the fall of the Qing dynasty, the mamianqun continued to be worn in the Republic of China, and only disappeared in the 1920s and 1930s [5] following the increased popularity of the cheongsam.[7] As a type of xifu, Chinese opera costumes, the mamianqun maintains its long tradition and continues to be worn nowadays.[2]: 54 In the 21st century, the mamianqun regained popularity with the emergence of the Hanfu movement.[8][9] The mamianqun has experienced various fashion changes throughout history.[10] It was typically paired with ku, Chinese trousers and Chinese jackets,[10][3][11] typically either the ao or gua.

Etymology

The term mamianqun (马面裙) is composed of three Chinese characters: ma《马》, which literally means 'horse'; mian《面》, which literally means "face"; and qun《裙》, which literally means "skirt".

In some 19th century French publications, the mamianqun were sometimes described as "deux jupes plissés" (transl. two pleated skirts).[12]: 314 [13]: 118 The name Paired apron has sometimes been used in English literature to refer to the mamianqun due to its construction of using two overlapping panels of fabric tied to a single waistband forming a single wrap skirt which is tied around the waist,[2]: 193 like an apron. The term Paired apron was coined by John Vollmer[14]: 25 in the second half of the 20th century and can be found as early as 1980s.[3]

Cultural significance and functionality

The mamianqun represents an important aesthetic and cultural concept in the life history of Chinese women as it is representative of the Zen aesthetic concept of "despising structure, emphasizing decoration, implicitly natural, and releasing the body"; this concept differs from the Western concept of emphasizing the structure and draping of the human body.[6] These skirts were only worn by Chinese women and were not worn by the Manchu women of the ruling class during the Qing dynasty.[10]

In the Qing dynasty, the mamianqun were also decorated with auspicious ornaments and patterns; these auspicious ornaments and pattern reflected the appropriate situational context and the social occasions in which its wearer partook; the colours and ornaments used in the mamianqun also had to be appropriate for the occasion and sometimes even reflected the interpersonal relationship between people during an important event, such as a wedding, and/or the social hierarchy between women in a household; e.g. a principal wife of the head of a household would wear a red skirt decorated with a Chinese dragon while a secondary wife was not allowed to wear red and had to wear green instead as red colour was an exclusive right for the first wife according to the legal code of the Qing dynasty.[3]

Due to the unique overlapping construction of the skirt, there were openings at the front and back of the skirt which facilitated horse-riding;[8][2]: 54 this characteristic would also allow for greater freedom of movement when walking, which was necessary for Chinese women who had bound feet who were walking with small and shuffling steps; the need for this kind of functional skirt when walking did not arise until the Song dynasty when foot binding became popular.[3] The pleats of pleats in Chinese skirts and its association to foot biding practice also appeared in European literature, such as in Intimate China: The Chinese as I Have Seen Them of 1899 by Mrs. Archibald Little:[15]: 182

"Their skirts [referring to the skirts of Chinese ladies] are very prettily made, in succession of tiny pleats longitudinally down the skirt, and only loosely fastened together over the hip, so as to feather round the feet when they move in the balancing way that Chinese poets liken to waving of the willow".

— Mrs. Archibald Little, Intimate China: The Chinese as I Have Seen Them (1899), p.182

Moreover, the fullness of the skirt created by the side panels provided enough space to accommodate the traditional loose garments of Chinese women.[3]

Construction and design

There are also many records of the mamianqun in European publication dating approximately mid-19th century which described the skirts of Chinese women, such as in La revue des deux mondes: volume 71 dating from the 1846, which describes the mamianqun as being a "deux jupes plissés" (transl. two pleated skirts), which is covered with luxurious designs; its skirt length is above the ankle-level allowing for the exposure of the large embroidered ku, Chinese trousers; the skirt is tied around the waist of its wearer.[12]: 314 Similar descriptions were found in the Voyage en Chine of 1847.[13]: 118

Main characteristics

The mamianqun is composed of two overlapping panel of fabrics which wrapped around the lower body.[16]: 144 Each of these two panels were identical and formed half of the skirt, which were then sewn together a single waistband[3] creating the overlapping front.[10] A mamianqun is a total of four flat and straight panels are known as qunmen (裙门; 'skirt door') or mamian (马面裙; 'horse face');[11] there are two flat panels at the right and left side of each panel of fabric. When worn, only two out of the four flat panels are visible on the wearer's body; the visible panels are seen located at the front and back of the skirt;[2]: 54 The mamianqun were typically tied with ties which extended beyond the skirt's width at the waistband.[16]: 144 [2]: 303

Skirt length

The historical mamianqun was made long enough to cover the ku, Chinese trousers, which were worn under the skirt.[3] However, variations in skirt length may have existed during the Qing dynasty as European accounts prior to the 1850s have sometimes described it as being above the ankle level and allowed the exposure of the trousers in 1846s[12]: 314 [note 1] while others have described it as being long enough to cover the feet in 1849s.[17]: 37 [note 2]

Pleats, gores, and trims

The historical mamianqun is typically decorated with pleated side panels,[1][2]: 54 gores, which can also vary in styles and types.[3][18] The use pleats, gores, and sometimes godet on the left side of the skirt allowed greater ease of movements when walking, allowing Chinese women to swing gracefully as they walked.[18] The trims which decorated mamianqun of the Qing dynasty did not only impacted the overall appearance of the skirt, but also influenced the way it would move as the wearer takes walk.[16]: 144 For example, depending on how the each trims were sewed to the edge of the pleats, the pleats may move independently from each other or create "ripple effects".[16]: 144

Types of pleats

Types of pleats used in the historical mamianqun: narrow pleats in honeycomb pattern or in fish-scale pattern,[18] knife pleats; and box pleat.[17]: 37

The pleats could also be a combination of knife pleats which radiate outwards to the left and right of a central box pleat located at the middle region of side hips.[19]: 55 [2]: 303 These types of pleats used in the mamianqun contrasted from the pleats used in the wide skirt of Western ladies as described by Samuel Wells William in 1849:[17]: 37

"One of the prettiest parts of a Chinese lady's dress is the petticoat, which appears about a foot below the upper robe covering the feet. Each side of the skirt is plaited about six times, and in front and rear are two pieces of Buckram to which they are attached; both the plaits and front pieces are stiffened with wire and lining. Embroidery is worked upon two pieces, and upon the plaits within and without in such a way that as the wearer steps, the action of the feet alternatively opens and shuts them on each side, disclosing the part or the whole of two different colored figures. The plaits are so contrived, that they are the same when seen in front or from behind, and the effect is more elegant when the colors are well contrasted. In order to produce this, the plaits close around the feet in just the contrary manner to the wide skirt of western ladies.

— Samuel Wells Williams, The Chinese Empire and Its Inhabitants: Being a Survey of the Geography, Government, Education, Social Life, Arts, Religion, &c. of the Middle Kingdom (1849), Volume 2, p.37

History: evolution and style variations

Wrap-around skirt artifacts worn by Chinese women, known under the generic term qun, appeared as early as the Zhou and Han dynasties.[3][16]: 144 Pleated skirts also appeared early on in China; according to the popular story, in the Han dynasty, pleated skirts became in vogue as women imitated the ripped skirt of Zhao Feiyan (? – 1 BC), a legendary dancer who later became an empress,[20] who had her skirt ripped when she was saved from a fall by Feng Wufang.[21]: 165 The term Mamianqun first appeared in the "History of the Ming Palace": "The drag and drop, the rear placket is continuous, and the two sides have swings, the front placket is two sections, and the bottom has horse face pleats, which rise to both sides. "But the history of the Mamianqun can be traced back to the Song Dynasty, because the skirt of the Song Dynasty already had the Mamian's shape of the Mamianqun.[22] However, the prototypes of the mamianqun originated in the Song (960 –1279 AD) and Liao dynasties (916 – 1125 AD).[5] The mamianqun experienced several changes of style, colours, fabric materials, and patterns over the dynasties.[5] The tailoring of the side panels, construction, and decoration of the skirt reflect changes in social and economic conditions during the time in which the skirts were made.[3]

Song and Liao dynasties

During the Song dynasty, the mamianqun first appeared and apparently could have absorbed some influences from the clothing worn by China's nomadic neighbours.[2]: 54 There are two forms of wrapped skirts which are related both to the early prototypes of the mamianqun and to the mamianqun which continued to be used in the Qing dynasty. Those two forms of wrapped skirts were found in the Song dynasty tomb of Huang Sheng in Fuzhou, Fujian Province.[16]: 144

The first mamianqun prototype skirt found in the Tomb of Huang Sheng was made of plain silk with a reinforcing layer at the centre of the skirt and patterned borders on one side, on the hem, and also on one side of the central panel.[16] It was made of 2 pieces of fabric which overlapped at the central region at the front and the back; the openings of the skirt allowed horseback riding.[2]: 54 It also had a wide waistband and was closed with ties;[2]: 54 the waistband was made from fabric which was different from the one used in the skirt.[3] However, the skirt was similar to a wrap-around skirt and had no pleats, thus restricting movement when compared to the pleated mamianqun of later centuries;[3] this form of skirt is known as liangpianqun (Chinese: 两片裙; pinyin: liǎngpiànqún; lit. 'two-piece skirt'),[23] also known as the xuanqun (Chinese: 旋裙; pinyin: xuánqún; lit. 'swirl skirt'), or whirling skirt in English.[24]: 55 According to the Jianglinjizazhi《江邻几杂志》of the Song dynasty:[25][24]: 55

"Women did not wear broad trousers [宽裤] and apron [襜], and for the convenience of donkey riding, the whirling skirt [xuanqun, 旋裙] must have openings at both the back and the front [必前后开胯]. This style was popular among female performers in the capital but it was admired and imitated by female members of the literati families, which was indeed a shame".

— Translated by Zhu et al, in A Social History of Middle-Period China: The Song, Liao, Western Xia and Jin Dynasties (2016), p.55

Horse riding and donkey riding was common in the Song dynasty as means of transportation; according to Wen Yanbo of the Northern Song dynasty, "upper-class families in town and countryside [...] all raised horses and rode them instead of walking" while in the History Narrated at Ease, volume 3, it is also recorded that "donkeys were for rent in the capital, and thus people often meet each other in the street on donkeys".[24]: 157–158 Donkey riding was not uncommon for Chinese women in this period. For example, Chinese women rode donkeys while playing luju, which was variation of the ancient version of polo, jiju (击鞠); the luju was a popular form of physical activity in the Song and Tang dynasties, and was often played by women and children as they perceived donkeys as being smaller, less violent and more manageable than horses.[26]: 40 Illustration of two elderly women riding donkeys and wearing veiled-hat, known as gaitou, can be found in the Song dynasty painting《Along the River During the Qingming Festival》.[27]: 73 [28]: 88 Similarly, a design of two-panel skirts worn by imperial concubines of the Southern Song dynasty during the reign of Emperor Lizong, known as ganshangqun (赶上裙), can be found in the Songshi.[29] The ganshangqun was also recorded as shangmaqun (上马裙) in the Xihuyoulan Zhiyu《西湖游览志余》of the Ming dynasty and maqun (马裙) in the Huayuehen《花月痕》of the Qing dynasty.[30] The ganshangqun was also derivative of the xuanqun.[31] Due to the novelty design of these skirts compared to the contemporary ordinary skirts of this period, they were considered as "qizhuangyifu (奇装异服; 'bizarre clothing')".[29]

The second prototype also comes from the Tomb of Huang Sheng; it was made of thin silk printed all over with large dots; this skirt was densely pleated except for the two sections at both edges of the skirt and the waistband was made of the same fabric as the skirt.[16]: 144 The pleats like the present-day mamianqun were also found on the two sides of the skirt.[2]: 54 This form of skirt is currently referred as baidiequn (百迭裙).

Yuan dynasty

In the Yuan dynasty, the mamianqun which was made of two fabrics and which could be found pleated appeared.[3] The waistband was made from fabric which was different from the one used in the skirt.[3]

Ming dynasty

In the Ming dynasty, the mamianqun was made of two fabrics and was deeply pleated.[3] The waistband was made from fabric which was different from the one used in the skirt.[3] The style of the mamianqun was considered as being pure and free of vulgarity.[5] Some women in the Ming dynasty also preferred light colours or white skirts as their favourite colours; this characteristic would later be transferred in the mamianqun used on stage in Peking opera.[2]: 193 It could also be decorated with a single or double lan, horizontal pattern, at the knee-level or at the hem of the skirt.[32]

Qing dynasty

In the Qing dynasty, Han Chinese women were allowed continue the dressing customs of the Ming dynasty and were not forced to adopt the hairstyle and dress of the Manchu rulers under the Tifayifu policy.[33]: 104 Therefore, Han Chinese women in the Qing dynasty continued to preserve Hanfu features in their dress and styles.[33]: 104 During this period, the mamianqun was a fashionable garments.[34] The style, however, progressively changed and the mamianqun became more luxurious.[5] The panels of fabric were decorated with embroideries; however, they were typically only embroidered to where the Chinese jackets would meet the skirt.[10] Compared to the skirts worn in the Ming dynasty, the skirts worn in the Qing dynasty also had a more structured appearance.[35]: 57

The tailoring of the mamianqun did not show significant changes except for the side panels which started to show some variations in terms of width and number of gores and the pleats techniques.[3] Style variations of the mamianqun in the Qing dynasty included the yuehuaqun (Chinese: 月华裙; lit. 'moon flower skirt'), which was also known as the 'moonlight skirt' and 'rainbow skirt' in English;[36][3][37] the fengweiqun (Chinese: 凤尾裙),[38] the yulinqun (Chinese: 釋魚裙), and the langanqun (Chinese: 阑干裙; also written as《栏杆裙》),[39] which gained their names based on their main characteristics and features differentiating them from other styles.

The waistband of the mamianqun in this period was larger than those worn in the previous dynasties.[3] The wide waistband was without decoration; it was also made of different materials than the main skirt. It was typically made of cheaper fabric than the rest skirt as it was hidden by the upper garments.[16] The main material used in the making of the skirt was typically silk while the choice of fabric for the waistband was usually cotton or hemp; the use of such cheaper fabric over silken fabric was also functional as it prevented the skirt from slipping from slipping down its wearer's body.[10][18] The mamianqun were also held by loops and buttons which were found inside the waistband.[3][10] Ties could also be used instead of loops and buttons.[18] Several historical mamianqun in its variant styles are stored in museums in and outside of China.[40][41][42]

Han women wearing the mamianqun skirt, which inherited the Ming style of clothing, was also influenced by Qing-style patterns, 19th century.

Han women wearing the mamianqun skirt, which inherited the Ming style of clothing, was also influenced by Qing-style patterns, 19th century. Female figurines wearing mamianqun, 19th century

Female figurines wearing mamianqun, 19th century Mamianqun, Qing dynasty, late 19th to early 20th century

Mamianqun, Qing dynasty, late 19th to early 20th century.jpg.webp) Knot buttons and loops used on the waistband of a mamianqun.

Knot buttons and loops used on the waistband of a mamianqun.

Yuehuaqun

The yuehuaqun (月华裙) was one of the most popular form of mamianqun style variant in the Qing dynasty;[33]: 104 It appeared at least since the 17th century where it was recorded by Li Yu (李漁):[10]

"Recently in Suzhou the fashionable 'hundred pleated skirt' (baijianqun;百襇裙) is considered very beautiful.… but there is a new style, the so-called 'moonlight skirt' (yuehuaqun; 月華裙) – with many colors set within each pleat, as if reflecting the light of a brightly lit moon".

The yuehuaqun was a skirt made of 12 gores, in which each gore consists of a different coloured fabric.[3] It was sometimes decorated with ribbons and small bells.[33]: 104

Fengweiqun

The fengweiqun (凤尾裙) appeared in the Qing dynasty during the Qianlong (r. 1735–96) period no later than 1750.[38] According to author, Shaorong Yang, embroidered fengweiqun with gold threads and made of damask was worn at the end of the Ming dynasty and at the beginning of the Qing dynasty.[43]: 45 It became the most popular style during the Kangxi (r. 1661–1722) and Qianlong period.[44]: 49 The fengweiqun was mostly worn by women who came from wealthy families, but women from less wealthy families may have possibly worn the fengweiqun as a wedding skirt.[44]: 50 This style continued even in the Republic of China period.

The fengweiqun was characterized by long and narrow strips of fabric with sharp bottom ends which could be sewn to the waistband of the skirt.[38][44]: 49 The strips of fabric could be made of silk and satin and embroidered with different patterns.[44]: 49 The edges of these fabric strips could also be decorated with gold threads or lace, which would make the skirt appear very luxurious.[44]: 49–50 It was sometimes decorated with ribbons and small bells.[33]: 104

Yulinqun

The yulinqun (lit. 'fish-scale skirt'), also known as the yulin baizhequn (lit. 'fish-scale hundred pleats'),[45]: 60 appeared in the late 19th century and became popular.[10] It was especially popular in Beijing in 1860s during the Tongzhi era.[45]: 60 [43]: 45 The yulinqun continues to be worn by actors in Peking opera.[2]: 193

The yulinqun has two overlapping flat panels and side pleats;[2]: 193 its main characteristic is the use of hundreds of tiny pleats which are then secured with an overlay of horizontal stitches in a wave pattern dividing these pleats into sections; the overlapping of these pleats would then give the impression of fish scales patterns.[10][45]: 60 The impression of fish scale-like is where the name skirt gained its name.

The pleats can also be secured to the skirt through the use of hand-made basting stitches on the inside in an alternating pattern; this would then create a honeycomb effect; this form of pleat effect were also referred as fish-scale pleating.[2]: 193

Langanqun

The langanqun (阑干裙 or 栏杆裙) was characterized with sharp trims (typically black in colour) in the shape of langan (Chinese: 欗杆; pinyin: lángān; lit. 'railing').[39]

Traditional wedding skirt and official attire for women

The mamianqun continued to be worn by Chinese brides who were allowed to follow the Ming dynasty clothing customs; there wedding attire were in the style of the Ming dynasty's women court attire.[46]: 46 The mamianqun was also worn on formal occasions along with ku, Chinese trousers, and other forms of Chinese jackets.[10] They were also used on festive occasions, such as family sacrificial rites and birthdays.[14]: 25

Fengweiqun

The fengweiqun might have been worn by women who came from less wealthy families as a wedding skirt on their wedding day.[44]

Mangqun

The mangqun (Chinese: 蟒裙; pinyin: mǎngqún; lit. 'python skirt'), also known as mangchu in English, could appear in the form of a mamianqun (and its variants). The mangqun formed part of the traditional Chinese wedding dress attire. It was either red or green in colour; it was worn together with the mangao, which is a loose ao, a Chinese jacket.[18] This skirt would be first worn on the wedding day of the bride; and following the wedding, she would have to wear it for any formal occasions.[18]

The mang (Chinese: 蟒; pinyin: mǎng; lit. 'python') was embroidered on the skirt; the mang was a creature which looked similar the long (Chinese: 龙), Chinese dragons, except that it had four claws instead of five and thus did not meet the contemporary definition of a long.[note 3]

Republic of China

In the Republic of China, the mamianqun was still being worn by Han Chinese women even at the time when the cheongsam was created in 1920s.[7] However, the style also changed, and the mamianqun eventually became unadorned[5] and became shorter in length.[11] In July 1912, the Senate published clear regulations on women's clothing known as Wenming xinzhuang (文明新裝) which had to continue the wearing aoqun tradition of the late Qing dynasty and did not break the thousand of years tradition of women dressing in yichang:[11]

"The upper garment is knee-length. It has collar, front opening, vents on the right, left and back hemline, with brocading ornaments on the whole body. The matched skirt has qunmen [which is also called mamian in Chinese, namely skirt panel, the surface with no pleats] at the front and the back. The right and left sides are pleated with ribbons on the top hem."

— Translated by Christopher Breward and Juliette MacDonald, Styling Shanghai (2020)

21st century

In the 21st century, the Ming-style mamianqun became a popular form of skirt for Hanfu enthusiasts.[8]

Modified, modern style

Ever since the beginning of the Hanfu movement around the year 2003, more modified, modern-style variations of the mamianqun based on the Ming dynasty design, such as shorter mamianqun (e.g. above the knee, mid-calf, and ankle length), mamianqun with pockets, have been developed over the past years by Chinese Hanfu designers and Hanfu enthusiasts.[47][48]

Some Hanfu enthusiasts sometimes combined the wearing of mamianqun with a T-shirt or blouse, and other contemporary garments, as an alternative to daily outwear and in opposition to the complete traditional style which looks more formal in style.[49]

Influences and derivatives

In Chinese opera

The mamianqun used as a type of qun, Chinese skirt, in xifu, Chinese opera costumes.[2]: 303 In Chinese opera, the mamianqun is often worn with a nüpi or a nüxuezi; this combination reflects one of the most common style of aoqun attire in the Ming dynasty consisting a knee-length, duijin shan (Chinese: 对襟衫) over a pleated skirt.[2]: 54–55

Styles of pleats used in the show the combination of a central box pleat with knife pleats radiating outwards at the right and left side of the central box pleats; the pleats are not found on the grain-line, allowing the creating of a slight flared skirt.[2]: 303 The size of the pleats, as well as its depth, reflect the different roles types of the actors and are used as distinguishing indicators.[2]: 55 For instances, mamianqun with relatively few pleats and/or wider pleats could be worn by Huadan.[2]: 193, 303 If tighter pleats were used, it was an indication of a person with a high status as tighter pleats requires more fabric.[2]: 193

In Jingqu, a traditional form of qun used is the yulinqun of the Qing dynasty.[2]: 193 It also inherited characteristics of the Ming dynasty mamianqun through its usage of light colours or white skirts, which were the preferred colours in the Ming dynasty.[2]: 193

Xiuhefu

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

The Xiuhefu (simplified Chinese: 秀禾服; traditional Chinese: 繡和服) is a two-pieces garment set of attire which was designed to look like a traditional Chinese wedding dress; it was developed in modern China and became popular in 2001 when it was popularized by when Zhou Xun, the actress who played the role of Xiu He, in the Chinese television drama Juzi Hongle《橘子紅了》(lit. 'Orange turned red'), thus gaining its contemporary name from name of the television drama character.[50][51]

The Xiuhefu is a modern recreation version of the Qing dynasty wedding aoqun which was worn by the Han Chinese women,[50][51] composed of a lower and an upper garment.[52] The qun used in the Xiuhefu is influenced by the historical mamianqun of the Qing dynasty, especially those used in the late years of the Qing dynasty in the 1910s,[50] which was used as part of the bridal attire.[51] This wedding skirt is also called mamianqun.[52]

In general, the design and construction of the Xiuhefu is not bound by any traditional clothing making rules.[50] The mamianqun used in the Xiuhefu can either be an A-line, pleated skirt[52] or a pleated circle skirt.[50][53] It has panels of flat fabric, which is embellished with decorative designs which uses an embroidery technique known as Chaoxiu (Chinese: 潮绣).[52] Compared to the historical mamianqun which has qunmen (裙门; 'skirt door') or mamian (马面裙; 'horse face') created by the overlapping characteristics of the skirt, the flat and straight panels of fabric used in the Xiuhefu are added on top of the pleated skirt, like a pendulum; it can also have more than two visible flat panels.[50][53]

Apparition and media

20st century

The Qing dynasty mamianqun made its apparition in the magazine Vogue published on the 15th December 2011 where it was presented as forming part of the "Boudoir Set" along with the Qing dynasty-style ao and Chinese shoes; Vogue also recommended that people shopped in Chinatown for the "Boudoir" set where it was a common place for Chinese women to wear the aoqun.[54]

Princess Diana's mamianqun

A red, mid-calf Qing dynasty langan-style mamianqun with chrysanthemum embroideries was worn by Princess Diana on the 23rd February 1981 prior to their official engagement announcement when she posed with Prince Charles at Clarence House.[55][56][57][note 4] The use of auspicious red colour was in line with Chinese wedding tradition; however, the skirt was not considered fully auspicious according to Chinese beliefs and traditions as it lacked the presence of a white belt (Chinese: 白色的束带; pinyin: báisède shùdài; lit. 'white colour belt') and instead a red one was used.[58][59] A mamianqun with a white coloured belt was usually worn by Chinese brides to symbolize "to grow old together", following the Chinese idiom baitou xielao (simplified Chinese: 白头偕老; traditional Chinese: 白頭偕老) which literally means '(to live together until the) white hairs of old age', which Princess Diana's skirt lacked of.[58][59] As a result, based on the Chinese wedding beliefs, the mamianqun of Princess Diana did not conform to the guiju (Chinese: 规矩; lit. 'established rules') and was instead considered buxiangde yuzhao (Chinese: 不祥的预兆; pinyin: bùxiángde yùzhào; lit. 'inauspicious omen').[58][59]

21st century

Following the Hanfu movement, the mamianqun re-appeared in several fashion magazines, including the Women's Wear Daily published on the 25th November 2020,[60] in Vogue published on the 8th March 2021,[61] in the Harper's Bazaar on the16th July 2021,[49]

The mamianqun also appeared in the animated film Turning Red (2022) by Domee Shi.

2022 Dior controversy

In 2022, French luxury fashion house Dior fell under heavy public criticism in China after the release of a new black flared, pleated midi-skirt for its Fall 2022 collection which was officially branded as its "hallmark silhouette".[62] This new skirt appeared earlier in an April 2022 runaway in Seoul, and according to the post-show notes of Maria Grazia Chiuri, Italian fashion designer and Dior's art director, the design of Fall 2022 collection was inspired by school uniforms and aimed to pay homage to women who contributed to the success of Christian Dior, which included his own sister Catherine Dior.[63][62][64] The new Dior skirt bore close resemblance to the mamianqun.[62] It was a wrap-around skirt, which was made of two panels of fabric which was sewn to the waistband of the skirt; it featured four flat panels with no pleats (one at each side of each panel of fabric) and pleats; it was constructed in an overlapping fashion such that there was two overlapping flat surface at the back and front and side pleats when worn.[65][66] On its official website page, this skirt was described as "a hallmark Dior silhouette, the mid-length skirt is updated with a new elegant and modern variation [...]".[67] On its official website page, this skirt was described as "a hallmark Dior silhouette, the mid-length skirt is updated with a new elegant and modern variation [...]" in English.[67]

In July 2022, Chinese netizens and Hanfu enthusiasts took notice of the skirt and observed that the new Dior skirt had the same construction of the historical mamianqun of the Ming dynasty with only its length as its main difference from its orthodox version being a midi-skirt.[62][68][66] However, the 21st century modern-style mamianqun based on the Ming dynasty design can also be found in mid-calf length.[48] Dior was thus accused of plagiarism as the new skirt was deemed to be "a copycat of a traditional Chinese garment"[66] and of cultural appropriation by Chinese netizens and official media outlets, such as the Global Times and the People's Daily,[62] for not acknowledge the (possible) Chinese origins of the new Dior skirt.[66][69][70] According to the Journal du Luxe, a French news media, the adoption of the mamianqun cut and construction design by Dior was not the main issue of the debate and critics but rather on the absence of transparency surrounding the origins of the inspirations behind the skirt design.[71] Some Chinese netizens also criticized Dior on Weibo with comments, such as "Was Dior inspired by Taobao?"[70] while another Instagram user commented on the official Dior account:[71]

"Les références culturelles à notre pays [Chine] sont plus que bienvenues mais cela ne signifie pas pour autant que vous pouvez détourner notre culture et nier le fait que cette jupe est chinoise !" [transl. "Taking cultural references from our country [i.e. China] is more than welcomed; however, this does not meaning that you can appropriate our culture and deny the fact that this skirt is Chinese !"].

— Instagram user, in Journal du Luxe, Dior : une polémique entre appropriation et transparence culturelle, published on July 21st 2022

Under these accusations, Dior did not immediately respond to a request for comment[66] and decided to stop this sale in the Mainland China's website to avoid controversy.[70] On July 23, about 50 Chinese overseas students in Paris made a protest in front of a Dior flagship store at Champs-Élysées,[72][73] they used the slogan "Dior, Stop Cultural appropriation" and "This is a traditional Chinese dress" written with a mixture of French and English,[74] and call for other overseas students from the United Kingdom and the United States for relay, the Communist Youth League of China also expressed support for this protest.[75] Similar protests are expected to take place worldwide, such as in New York, United States, and London, United Kingdom.[76]

Related content

See also

- Hanfu

- List of Hanfu

- Maweiqun - an underskirt introduced in Ming dynasty China from Joseon

Gallery

- Mamianqun outside China

.jpg.webp)

Chinese bride in Batavia, 1870

Chinese bride in Batavia, 1870 Chinese woman in Singapore, c. 1890

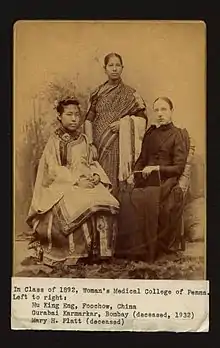

Chinese woman in Singapore, c. 1890 Hu King Eng, members of class 1892 at the Woman's Medical College of Pennsylvania

Hu King Eng, members of class 1892 at the Woman's Medical College of Pennsylvania Dr. Hu King Eng, Philadelphia, unknown date

Dr. Hu King Eng, Philadelphia, unknown date.jpg.webp)

_(cropped).jpg.webp) Chinese mother and daughter wearing mamianqun, Los Angeles, United States, c. 1900

Chinese mother and daughter wearing mamianqun, Los Angeles, United States, c. 1900.jpg.webp) Young Chinese woman, Los Angeles, United States, c. 1920

Young Chinese woman, Los Angeles, United States, c. 1920_(8026561873).jpg.webp) Concert de musique chinoise Nanguan, Auditorium du musée Guimet, France, 25 septembre 2012

Concert de musique chinoise Nanguan, Auditorium du musée Guimet, France, 25 septembre 2012

Notes

- ↑ La revue des deux mondes (1846) described the length of skirts of Chinese women belonging to the wealthy families

- ↑ Williams (1849) described the length of skirts of the gentlewomen as being long enough to cover the feet

- ↑ See page Chinese dragons and page Mangfu for more detailed explanation on the evolution of Chinese dragons and mang, as well as it is differentiating characteristics.

- ↑ For video of footage of Princess Diana wearing the Mamianqun, see external link

References

- 1 2 "Skirt (China), 19th century". Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum. Retrieved 2021-07-07.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 Bonds, Alexandra B. (2008). Beijing opera costumes : the visual communication of character and culture. Honolulu: University of Hawaiʻi Press. ISBN 978-1-4356-6584-2. OCLC 256864936.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 Hays, Mary V (1989). "Chinese Skirts of the Qing dynasty" (PDF). The Bulletin of the Needle and Bobbin Club. 72: 4–42.

- ↑ Liu, Xiaoju. "马面裙的款式结构研究--《西部皮革》2019年23期" [zh:Research on the Style and Structure of Horse Face Skirts]. www.cnki.com.cn. Retrieved 2022-07-28.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 "From the Slitting Skirt to the Absorbing Essence,History of Art Development about the Horse-face Apron--《Art and Design》2016年10期". en.cnki.com.cn. CAO Xue; WANG Qun-shan; Beijing Institute of Fashion Technology. Retrieved 2021-07-07.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - 1 2 Li, Hongmei. "明清马面裙的形制结构与制作工艺--《纺织导报》2016年11期" [zh:The shape structure and production process of horse face skirt in Ming and Qing Dynasties]. www.cnki.com.cn. Retrieved 2022-07-28.

- 1 2 Liu, Yu (2017-10-01). "Westernization and the consistent popularity of the Republican qipao". International Journal of Fashion Studies. 4 (2): 211–224. doi:10.1386/infs.4.2.211_1. ISSN 2051-7106.

- 1 2 3 "Meet Shiyin, the Fashion Influencer Shaping China's Hanfu Style Revival". Vogue. 8 March 2021. Retrieved 2021-07-07.

- ↑ 张洁. "Young culture fans dress to impress". global.chinadaily.com.cn. p. 1. Retrieved 2021-07-07.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 "A Poetic Skirt | Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum". www.cooperhewitt.org. 2016-06-06. Retrieved 2022-08-01.

- 1 2 3 4 Styling Shanghai. Christopher Breward, Juliette MacDonald. London, UK. 2020. ISBN 978-1-350-05114-0. OCLC 1029205918.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) CS1 maint: others (link) - 1 2 3 La revue des deux mondes (pdf) (in French). Vol. 71. Paris: Bureau de la Revue des Deux Mondes. 1846.

- 1 2 Bonacossi; Hausmann (1847). Voyage en Chine (pdf) (in French). V. Devroede.

- 1 2 Mailey, Jean (1980). The Manchu dragon : costumes of the Chíng dynasty 1644-1912. The Metropolitan Museum of Art. OCLC 473225869.

- ↑ Mrs. Archibald Little (1899). Intimate China: The Chinese as I Have Seen Them (PDF). Hutchinson & Company. ISBN 9780461098969.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Dusenberry, Mary M. (2004). Flowers, dragons and pine trees : Asian textiles in the Spencer Museum of Art. Carol Bier, Helen Foresman Spencer Museum of Art (1st ed.). New York: Hudson Hills Press. p. 144. ISBN 1-55595-238-0. OCLC 55016186.

- 1 2 3 Williams, Samuel Wells (1849). The Chinese Empire and Its Inhabitants: Being a Survey of the Geography, Government, Education, Social Life, Arts, Religion, &c. of the Middle Kingdom (PDF). Vol. 2. H. Washbourne.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Garrett, Valery (2012). Chinese Dress : From the Qing Dynasty to the Present. New York: Tuttle Pub. ISBN 978-1-4629-0694-9. OCLC 794664023.

- ↑ Singer, Ruth (2008). The sewing bible : a modern manual of practical and decorative sewing techniques (First American ed.). New York. ISBN 978-0-7704-3468-7. OCLC 882915138.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ↑ Yao, Ping (2022). Women, gender and sexuality in China : a brief history (First ed.). Abingdon, Oxon. ISBN 978-1-315-62726-7. OCLC 1273727859.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ↑ Milburn, Olivia (2021). The empress in the Pepper Chamber : Zhao Feiyan in history and fiction. Seattle. ISBN 978-0-295-74876-4. OCLC 1238129666.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ↑ Qi Ziyu. Research on the Shape of Horse Face Skirts in Qing Dynasty[D]. Beijing Institute of Fashion Technology, 2012.

- ↑ "宋朝的"包臀裙"——宋制两片裙,触及到你的知识盲区了吗?_腾讯新闻". new.qq.com (in Chinese). Retrieved 2021-07-08.

- 1 2 3 Zhu, Ruixi; 朱瑞熙 (2016). A social history of middle-period China : the Song, Liao, Western Xia and Jin dynasties. Bangwei Zhang, Fusheng Liu, Chongbang Cai, Zengyu Wang, Peter Ditmanson, Bang Qian Zhu (Updated ed.). Cambridge, United Kingdom. ISBN 978-1-107-16786-5. OCLC 953576345.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ↑ "旋裙 - 《中国大百科全书》第三版网络版" [Xuanqun -《Encyclopedia of China Publishing House》Third edition, Online edition]. www.zgbk.com. Retrieved 2022-08-02.

- ↑ Sport and physical education in China. James Riordan, Robin Jones. London: E & FN Spon. 1999. ISBN 0-203-47699-9. OCLC 51746358.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ↑ Xu, Man (2016). Crossing the Gate : Everyday Lives of Women in Song Fujian (960-1279). Roger T. Ames. Albany, NY. ISBN 978-1-4384-6322-3. OCLC 950004342.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ↑ Johnson, Linda Cooke (2011). Women of the conquest dynasties : gender and identity in Liao and Jin China. Honolulu: University of Hawaiʻi Press. ISBN 978-0-8248-6024-0. OCLC 794925381.

- 1 2 "赶上裙 - 《中国大百科全书》第三版网络版" [Ganshangqun-《Encyclopedia of China Publishing House》Third edition, Online edition]. www.zgbk.com. Retrieved 2022-08-02.

- ↑ "上马裙 - 《中国大百科全书》第三版网络版" [Shangmaqun-《Encyclopedia of China Publishing House》Third edition, Online edition]. www.zgbk.com. Retrieved 2022-08-02.

- ↑ Hua mei (2018). Zhong guo fu zhuang shi : 2018 ban 中国服装史:2018版 (Di 1 ban ed.). Beijing: Zhong guo fang zhi chu ban she. ISBN 978-7-5180-5012-3. OCLC 1097969996.

- ↑ "4 Secrets about Hanfu Ma Mian Qun - 2022". www.newhanfu.com. 2019-11-08. Retrieved 2022-08-09.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Fang, Huawen (2015). Traditional Chinese folk customs. Weihua Zhang, Zhengming Du. Newcastle upon Tyne. ISBN 978-1-4438-8455-6. OCLC 924632370.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ↑ Wang, Anita Xiaoming (2018). "The Idealised Lives of Women: Visions of Beauty in Chinese Popular Prints of the Qing Dynasty". Arts Asiatiques. 73: 61–80. doi:10.3406/arasi.2018.1993. ISSN 0004-3958. JSTOR 26585538.

- ↑ Silberstein, Rachel (2020). A fashionable century : textile artistry and commerce in the late Qing. Seattle. ISBN 978-0-295-74719-4. OCLC 1121420666.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ↑ "Yuehuaqun" 月华裙. www.chinasilkmuseum.com (in Chinese). 2017-12-29. Retrieved 2022-07-16.

- ↑ "Han Women's Style". Chinese Traditional Dress - Online exhibitions across Cornell University Library. Retrieved 2021-07-08.

- 1 2 3 Gao, Bingqing (2015). "凤尾裙小考" [A Study of The Chinese Traditional Phoenix-Tail-Designed Dress]. The Palace Museum. Retrieved 2022-07-28.

- 1 2 "Sanlanxiu taiping fuguiwen langanqun" 三蓝绣太平富贵纹栏杆裙. www.chinasilkmuseum.com. 2017-12-29. Retrieved 2022-07-16.

- ↑ "Woman's Skirt (mamian qun)". collections.rom.on.ca. Retrieved 2021-07-07.

- ↑ "Woman's skirt (mamian qun)". collections.rom.on.ca. Retrieved 2021-07-07.

- ↑ Wien, Weltmuseum (2017-10-30). "Weltmuseum Wien: Pleated wrap-skirt". www.weltmuseumwien.at. Retrieved 2021-07-07.

- 1 2 Yang, Shaorong (2004). Traditional Chinese clothing : costumes, adornments & culture (1st ed.). San Francisco: Long River Press. ISBN 1-59265-019-8. OCLC 52775158.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Hua, Mei (2011). Chinese clothing (Updated ed.). Cambridge, United Kingdom. ISBN 978-0-521-18689-6. OCLC 781020660.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - 1 2 3 Finnane, Antonia (2008). Changing clothes in China : fashion, history, nation. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-14350-9. OCLC 84903948.

- ↑ Vollmer, John E. (2007). Dressed to rule : 18th century court attire in the Mactaggart Art Collection. Mactaggart Art Collection. Edmonton: University of Alberta Press. p. 46. ISBN 978-1-55195-214-7. OCLC 166687933.

- ↑ "The Mamianqun: History, Construction, Features - 2022". www.newhanfu.com. 2022-07-18. Retrieved 2022-07-28.

- 1 2 Koetse, Manya. "Mamianqun Gate: Dior Accused of Cultural Appropriation for Copying Design of Traditional Chinese Skirt". Retrieved 2022-08-03.

- 1 2 Zheng, Jane (2021-07-16). "A return to tradition: how Hanfu returned as a modern style statement". Harper's BAZAAR. Retrieved 2022-07-17.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "Xiu He Fu | Traditional Chinese Wedding Costume". Jin Weddings. Retrieved 2022-08-09.

- 1 2 3 Li, Yuling (2019). New meaning in traditional wedding dresses – Xiu He Fu and Long Feng Gua – in contemporary China / Li Yuling (masters thesis). University of Malaya.

- 1 2 3 4 JNTT (2020-07-30). "SAME SAME BUT DIFFERENT". The Red Wedding. Retrieved 2022-08-09.

- 1 2 "Xiuhe cheongsam, a wedding dress, Xu Yishiqing". iNews. 2021-02-17.

- ↑ Chan, Heather (2017). "From Costume to Fashion: Visions of Chinese Modernity in Vogue Magazine, 1892-1943". Ars Orientalis. 47 (20220203). doi:10.3998/ars.13441566.0047.009. hdl:2027/spo.13441566.0047.009. ISSN 2328-1286.

- ↑ Hanmer, Davina (1984). Diana, the fashion princess. Tim Graham (1st American ed.). New York: Holt, Rinehart, and Winston. ISBN 0-03-072068-0. OCLC 10375648.

- ↑ Princess Diana poses with Charles. 2011.

- ↑ "Lady Diana: Die Stationen ihres Lebens in Bildern". Die Presse (in German). 2017-08-28. p. 3. Retrieved 2022-07-15.

- 1 2 3 "40 years ago, Diana wore a Chinese horse-faced skirt to the dinner party, but she didn't wear the right one, hiding the ominous signs". iNews. 2022.

- 1 2 3 "穿马面裙、带两块手表,戴安娜对查尔斯的爱意,那么浓厚而内敛". inf.news. 2022.

- ↑ Zhang, Tianwei (2020-11-25). "Putting China's Traditional Hanfu on the World Stage". WWD. Retrieved 2022-07-17.

- ↑ "Meet Shiyin, the Fashion Influencer Shaping China's Hanfu Style Revival". Vogue. 2021-03-08. Retrieved 2022-07-17.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Cultural appropriation vs appreciation: Can luxury brands in China tell the difference? | Marketing". Campaign Asia. Retrieved 2022-08-03.

- ↑ "Discover Dior's Pre-Fall 2022 Collection". A&E Magazine. 2022-07-14. Retrieved 2022-08-03.

- ↑ UK, FashionNetwork com. "Christian Dior Pre-Fall 2022: The sisters are doin' it for themselves". FashionNetwork.com. Retrieved 2022-08-03.

- ↑ Cultural Appropriation|I bought Dior's $3800 skirt & It is a copycat of Chinese Mamianqun, retrieved 2022-08-03

- 1 2 3 4 5 Hu, Denni (2022-07-18). "Dior Sparks Online Criticism for Traditional Chinese Dressing Design". WWD. Retrieved 2022-08-03.

- 1 2 "Dior faces criticisms over new skirt resembling ancient Chinese clothing". www.marketing-interactive.com. Retrieved 2022-08-03.

- ↑ ""迪奥抄袭"引热议,网友:公开抄袭中国马面裙". Changjiang Cloud (in Chinese (China)). 2022-07-16.

- ↑ "Chinese netizens slam Dior over 'cultural appropriation'". SHINE. Retrieved 2022-08-03.

- 1 2 3 "$3,800 Dior Skirt Accused of Appropriating Chinese Culture". www.vice.com. Retrieved 2022-08-03.

- 1 2 "Dior : une polémique entre appropriation et transparence culturelle". journalduluxe.fr (in French). Retrieved 2022-08-03.

- ↑ "留法中国学生抗议迪奥"文化挪用"". Deutsch Welle (in Chinese (China)). 2022-07-24.

- ↑ 曾婷瑄 (2022-07-23). "巴黎中國留學生抗議Dior抄襲 反示威者:裙子比人權重要?". CNA (in Chinese (Taiwan)). Paris.

- ↑ Oscar Holland. "Dior accused of 'culturally appropriating' centuries-old Chinese skirt". CNN. Retrieved 2022-08-03.

- ↑ Shamuratov, J; Alimbaev, M (2022-05-30). "The significance of technology in teaching l2". Ренессанс в парадигме новаций образования и технологий в XXI веке (1): 214–216. doi:10.47689/innovations-in-edu-vol-iss1-pp214-216. ISSN 2277-3010.

- ↑ Hu, Denni (2022-07-25). "Hanfu Supporters Protest Outside Dior Over Disputed Skirt Design". WWD. Retrieved 2022-08-03.

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

_-_1916.1349.b_-_Cleveland_Museum_of_Art.tif.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

_(mamianqun_and_yesa).jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

%252C_China%252C_Qing_Dynasty%252C_c._1880-1900%252C_damask_and_satin_-_Patricia_Harris_Gallery_of_Textiles_%2526_Costume%252C_Royal_Ontario_Museum_-_DSC09380.JPG.webp)

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

.JPG.webp)