James Douglas | |

|---|---|

| Earl of Mar Earl of Douglas | |

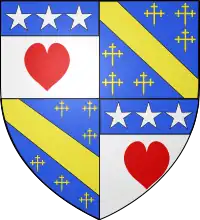

Seal of the 2nd Earl of Douglas and Mar | |

| Predecessor | William Douglas, 1st Earl of Douglas |

| Successor | Archibald Douglas, 3rd Earl of Douglas |

| Born | 1358 Scotland |

| Died | 5 or 19 August 1388 killed at Otterburn, Northumberland |

| Buried | 1388 Melrose Abbey[1] |

| Noble family | Douglas |

| Issue | William Douglas of Drumlanrig (illegitimate) Archibald Douglas (illegitimate) |

| Father | William Douglas, 1st Earl of Douglas |

| Mother | Margaret, Countess of Mar |

Sir James Douglas, 2nd Earl of Douglas and Mar (c. 1358 – 5 or 19 August 1388) was an influential and powerful magnate in the Kingdom of Scotland.

Early life

He was the eldest son and heir of William Douglas, 1st Earl of Douglas and Margaret, Countess of Mar. By the time his father had made over lands in Liddesdale to him in 1380, he had been knighted, being known as Sir James Douglas of Liddesdale.[2] Earlier his father had been in dispute with King Robert over the latter's succession to King David II, but returned to royal favour by concluding a marriage contract between his son and the Princess Isabel, thus binding the Douglas family close to the throne.[3]

Earl of Douglas and Mar

In May 1384, the 1st Earl of Douglas died from a fever, and his son inherited.[4] Around the same time a French embassy arrived in Scotland to negotiate a truce between the Franco-Scots Allies and England. While deliberations were taking place in Edinburgh, a further party of French knights arrived at Montrose. These adventurers led by Geoffroi de Charny, sent word to the court at Edinburgh, from Perth where they had marched to, in which they offered their services against the English.[5] The new Earl of Douglas, and Sir David Lindsay mustered their men and joined forces with the French knights. They then led a raid into England where they ravaged lands belonging to the Percy Earl of Northumberland, and the Mowbray Earl of Nottingham.[6] While this Chevauchée was happening, the Scots agreed to the tripartite truce on 7 July which was to last until May the following year. De Charny and his knights returned to France but promised to Douglas that they would return as soon as possible.

In 1385 when the truce expired, Douglas made war on the English.[7] The French were as good as their word and had previously arrived at Leith with a contingent of Chivalry, armour and monies. The French under Jean de Vienne, Admiral of France joined forces with the Scots. Finding that the army of Richard II of England was numerically superior to the Franco-Scots, Douglas allowed the English to advance to Edinburgh, wisely refusing battle, the English army destroyed the Abbies of Melrose, Newbattle and Dryburgh, as well as burning the burgh of Haddington and the capital itself. Douglas contented himself with a destructive counter-raid on Carlisle and Durham, leading the French, and the men of Galloway, under his cousin Archibald the Grim. Disputes soon arose between the allies, and the French returned home at the end of the year.

1386 saw squabbling between the Earl of Northumberland, and John Neville, 3rd Baron Neville de Raby over the wardenship of the Eastern March. Roger de Clifford, 5th Baron de Clifford, the warden of the Western March, was engaged to keep the peace between the rivals. While Clifford was away from his duties in the west, Douglas accompanied by the Earl of Fife led a force deep into Cumberland, and raided and burnt the town of Cockermouth.[8]

Otterburn and death

_Percy%252C_Battle_of_Otterburn.jpg.webp)

Invasion of England

In 1388 Richard II had domestic troubles with his recalcitrant barons and was occupied far to the south, and the time seemed right for invasion to avenge the destruction of 1385.

The Scots, following an agreement made between the nobility at Aberdeen, mustered at Jedburgh in August, including the levies of the earls of Fife, March, Moray and those of Archibald the Grim. Upon finding from an English spy, that the English warden Percy was aware of the muster, and was planning a counter strike, the Scots command decided to split the army, with Fife leading the main body into Cumberland, while a smaller mounted force under Douglas was to go east and despoil Northumberland.

Douglas' force entered England through Redesdale and proceeded south to Brancepeth laying waste to the countryside. From there the turned east to encircle Newcastle.

Newcastle was held by Northumberland's sons, Sir Henry Percy, known as "Hotspur", and his brother Sir Ralph Percy. Northumberland himself remained at Alnwick Castle, hoping to outflank Douglas should he attempt to return to Scotland.

The Scots, without the siege equipment to invest the Castle, encamped around it. The week that followed saw constant skirmishes and challenges to single combat between the two sides, that culminated when Douglas challenged Hotspur to a duel. In the ensuing joust Douglas successfully felled Hotspur and was able to capture his pennon. According to Froissart, Douglas announced that he would "carry [the pennon] to Scotland and hoist it on my tower, where it may be seen from afar", to which Hotspur retorted "By God! You will never leave Northumberland alive with that."

Battle of Otterburn

The following day the Scots struck camp and marched to Ponteland where they destroyed its castle, and then on to Otterburn just 30 miles from Newcastle, Douglas appeared to be tarrying to see whether Hotspur would react.

Douglas chose his encampment in a wood with an eye to protect his force from English archery. But on the evening of 5 or 19 August, the Percies surprised the Scots and a bloody moonlit battle ensued. Douglas was mortally wounded during the fight, but because of the confusion of fighting in darkness this fact was not transmitted to his men who carried on the battle. Froissart gives account in detail of the various individuals wounded, captured or killed, but what is known is that the Scots won the encounter taking Hotspur and many others prisoner. Douglas' body was found on the field the following day. The Scots, albeit saddened by the loss of their leader, were heartened enough by the victory, to frighten off English reinforcements led by Walter Skirlaw, the Bishop of Durham the following day.

Douglas' body was then removed back across the Border and he was interred at Melrose Abbey.

The battle, as narrated by Jean Froissart, forms the basis of the English and Scottish ballads The Ballad of Chevy Chase and The Battle of Otterburn.

Marriage and issue

Douglas married Isabel, a daughter of King Robert II of Scotland. He left no legitimate male issue. His natural sons William and Archibald became the ancestors of the families of Douglas of Drumlanrig (see Marquess of Queensberry) and Douglas of Cavers. His sister Isabel inherited the lands and earldom of Mar, and the unentailed estates of Douglas. Isabel arranged for the Bonjedward estate to be passed to their half-sister, Margaret, who became 1st Laird of Bonjedward.

The earldom and entailed estates of Douglas reverted by the patent of 1358 to Archibald Douglas, called "The Grim", cousin of the 1st Earl and a natural son of The "Good" Sir James Douglas.

References

Sources

- Sadler, John, Border Fury-England and Scotland at War 1296-1568. Pearson Education. 2005.

- Brown Michael, Black Douglases: War and Lordship in Late Medieval Scotland, 1300-1455. Tuckwell Press. 1998

- Maxwell, Sir Herbert, A History of the House of Douglas II vols. London. 1902

- Brenan, Gerald, A History of the House of Percy II vols. London 1902

- Fraser, Sir William, The Douglas Book IV vols. Edinburgh. 1885

- The Records of the Parliaments of Scotland to 1707 , K.M. Brown et al. eds (St Andrews, 2007–2011).

- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Douglas". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 8 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 442–444.

Further reading

- Tranter, Nigel, The Stewart Trilogy, Dunton Green, Sevenoaks, Kent : Coronet Books, 1986. ISBN 0-340-39115-4. Lords of Misrule, 1388-1396. A Folly of Princes, 1396-1402. The Captive Crown, 1402-1411.

- thepeerage.com