An isoquant (derived from quantity and the Greek word iso, meaning equal), in microeconomics, is a contour line drawn through the set of points at which the same quantity of output is produced while changing the quantities of two or more inputs.[1][2] The x and y axis on an isoquant represent two relevant inputs, which are usually a factor of production such as labour, capital, land, or organisation. An isoquant may also be known as an “Iso-Product Curve”, or an “Equal Product Curve”.

Isoquants vs. indifference curves

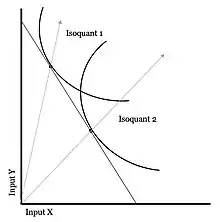

While an indifference curve mapping helps to solve the utility-maximizing problem of consumers, the isoquant mapping deals with the cost-minimization and profit and output maximisation problem of producers. Indifference curves further differ to isoquants, in that they cannot offer a precise measurement of utility, only how it is relevant to a baseline. Whereas, from an isoquant, the product can be measured accurately in physical units, and it is known by exactly how much isoquant 1 exceeds isoquant 2.

Nature and practical uses

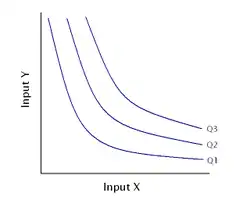

In managerial economics, isoquants are typically drawn along with isocost curves in capital-labor graphs, showing the technological tradeoff between capital and labor in the production function, and the decreasing marginal returns of both inputs. In managerial economics, the unit of isoquant is commonly the net of capital cost. As such, isoquants by nature are downward sloping due to operation of diminishing marginal rates of technical substitution (MRTS).[3][4] The slope of an isoquant represents the rate at which input x can be substituted for input y.[5] This concept is the MRTS, so MRTS=slope of the isoquant. Thus, the steeper the isoquant, the higher the MRTS. Since MRTS must diminish, isoquants must be convex to their origin. Adding one input while holding the other constant eventually leads to decreasing marginal output.

The contour line of an isoquant represents every combination of two inputs which fully maximise a firms’ use of resources (such as budget, or time). Full maximisation of resources is usually considered ‘efficient’. Efficient allocation of factors of production occur only when two isoquants are tangent to one another. If a firm produces to the left of the contour line, then the firm is considered to be operating inefficiently, because they are not maximising use of their available resources.[6] A firm cannot produce to the right of the contour line unless they exceed their constraints.

A family of isoquants can be represented by an isoquant map, a graph combining a number of isoquants, each representing a different quantity of output.An isoquant map can indicate decreasing or increasing returns to scale based on increasing or decreasing distances between the isoquant pairs of fixed output increment, as output increases.[7] If the distance between those isoquants increases as output increases, the firm's production function is exhibiting decreasing returns to scale; doubling both inputs will result in placement on an isoquant with less than double the output of the previous isoquant. Conversely, if the distance is decreasing as output increases, the firm is experiencing increasing returns to scale; doubling both inputs results in placement on an isoquant with more than twice the output of the original isoquant. A firm can choose to utilise the information an isoquant gives on returns to scale, by using it as insight how to allocate resources.[8]

Knowing how to allocate resources is a concept pertinent to managerial economics. Isoquants can be useful to graphically represent this issue of scarcity. They show the extent to which the firm in question has the ability to substitute between two different inputs (x and y in the graph) at will in order to produce the same level of output (see: Graph C)). They also represent different quantity combinations of two goods which adhere to a budget constraint. Thus, they can be used as a tool to help management make better informed decisions regarding production and profit dilemmas, such as cost or waste minimization, and revenue and output maximization.

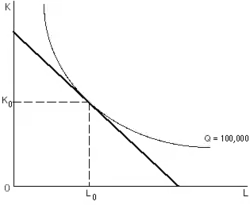

A firm can determine the least cost combination of inputs to produce a given output, by combining isocost curves and isoquants, and adhering to First Order Conditions.[3] The least cost combination is where the ratio of marginal products is equal to the ratio of factor prices. At this point, the slope of the isoquant, and the slope of the isocost, will be equal (see intersection of graph D). A firm has incentive to produce at the least cost combination because it is at this point, the related costs of desired production are minimised.[9]

As with indifference curves, two isoquants can never cross. Also, every possible combination of inputs is on an isoquant. Finally, any combination of inputs above or to the right of an isoquant results represents a higher level of output, and vice versa. Although the marginal product of an input decreases as you increase the quantity of the input while holding all other inputs constant, the marginal product is never negative in the empirically observed range since a rational firm would never increase an input to decrease output.

Shapes

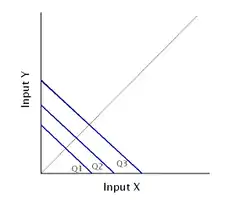

If the two inputs are perfect substitutes, the resulting isoquant map generated is represented in fig. A; with a given level of production Q3, input X can be replaced by input Y at an unchanging rate. The perfect substitute inputs do not experience decreasing marginal rates of return when they are substituted for each other in the production function.

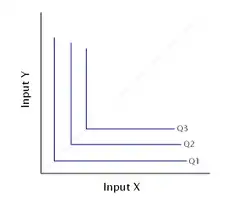

If the two inputs are perfect complements, the isoquant map takes the form of fig. B; with a level of production Q3, input X and input Y can only be combined efficiently in the certain ratio occurring at the kink in the isoquant. The firm will combine the two inputs in the required ratio to maximize profit.

Isoquants are typically combined with isocost lines in order to solve a cost-minimization problem for given level of output. In the typical case shown in the top figure, with smoothly curved isoquants, a firm with fixed unit costs of the inputs will have isocost curves that are linear and downward sloped; any point of tangency between an isoquant and an isocost curve represents the cost-minimizing input combination for producing the output level associated with that isoquant. A line joining tangency points of isoquants and isocosts (with input prices held constant) is called the expansion path.[10]

Non-convexity

Under the assumption of declining marginal rate of technical substitution, and hence a positive and finite elasticity of substitution, the isoquant is convex to the origin. A locally nonconvex isoquant can occur if there are sufficiently strong returns to scale in one of the inputs. In this case, there is a negative elasticity of substitution - as the ratio of input A to input B increases, the marginal product of A relative to B increases rather than decreases.

A nonconvex isoquant is prone to produce large and discontinuous changes in the price minimizing input mix in response to price changes. Consider for example the case where the isoquant is globally nonconvex, and the isocost curve is linear. In this case the minimum cost mix of inputs will be a corner solution, and include only one input (for example either input A or input B). The choice of which input to use will depend on the relative prices. At some critical price ratio, the optimum input mix will shift from all input A to all input B and vice versa in response to a small change in relative prices.

See also

References

- ↑ Varian, Hal R. (1992). Microeconomic Analysis (Third ed.). Norton. ISBN 0-393-95735-7.

- ↑ Chiang, Alpha C. (1984). Fundamental Methods of Mathematical Economics (Third ed.). McGraw-Hill. pp. 359–363. ISBN 0-07-010813-7.

- 1 2 www2.econ.iastate.edu http://www2.econ.iastate.edu/classes/econ101/choi/ch11d.htm. Retrieved 2021-04-25.

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|title=(help) - ↑ "Isoquants". www.economics.utoronto.ca. Retrieved 2021-04-25.

- ↑ "Production Functions" (PDF). UCLA. n.d. Retrieved 25 April 2021.

- ↑ Arrow, K. J.; Chenery, H. B.; Minhas, B. S.; Solow, R. M. (1961). "Capital-Labor Substitution and Economic Efficiency". The Review of Economics and Statistics. 43 (3): 225–250. doi:10.2307/1927286. ISSN 0034-6535. JSTOR 1927286.

- ↑ Kwatiah, Natasha (2016-03-02). "The Laws of Returns to Scale in Terms of Isoquant Approach". Economics Discussion. Retrieved 2021-04-25.

- ↑ "The Discovery of the Isoquant". ResearchGate. Retrieved 2021-04-25.

- ↑ "Expansion path, ridgeline and least cost combination of inputs" (PDF). Eagri. n.d. Retrieved 2021-04-25.

- ↑ Salvatore, Dominick (1989). Schaum's outline of theory and problems of managerial economics, McGraw-Hill, ISBN 978-0-07-054513-7