Indian Mills, New Jersey | |

|---|---|

_at_Burlington_County_Route_620_(Medford-Indian_Mills_Road)_in_Shamong_Township%252C_Burlington_County%252C_New_Jersey.jpg.webp) | |

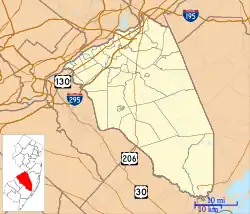

Indian Mills Location of Indian Mills in Burlington County (Inset: Burlington County in New Jersey)  Indian Mills Indian Mills (New Jersey)  Indian Mills Indian Mills (the United States) | |

| Coordinates: 39°47′38″N 74°44′40″W / 39.79389°N 74.74444°W | |

| Country | |

| State | |

| County | Burlington |

| Township | Shamong |

| Elevation | 75 ft (23 m) |

| GNIS feature ID | 877333[1] |

Indian Mills, formerly known as Brotherton, is an unincorporated community located within Shamong Township in Burlington County, in the U.S. state of New Jersey.[2] It was the site of Brotherton Indian Reservation, the only Indian reservation in New Jersey and the first in America, founded for the Lenni Lenape tribe, some of whom were native to New Jersey's Washington Valley.[3][4]

Before becoming a reservation, it was an industrial town, known for gristmills and sawmills. Brotherton was the first Native American reservation in New Jersey.[5]

The town was also historically known as Edgepillock[3] or Edgepelick.[6]

History

In 1756, the British colonial government appointed commissioners to resolve disputes between white settlers and the Munsee Lenape native to the Washington Valley. For 100 years prior, the groups had been on peaceful terms.[3]

In 1757, the "New Jersey Association for Helping the Indians"[7] wrote a constitution to expel Munsee Lenape native to the Washington Valley. Led by Reverend John Brainerd, colonists forcefully relocated 200 people to Indian Mills, then known as Brotherton.[4]

In 1777, Reverend John Brainerd abandoned the reservation, making circumstances increasingly difficult.[8]

In 1780, Munsee Lenape community leaders of Brotherton, native to Washington Valley, wrote a community treaty[9][8] to oppose selling any more land to white settlers:

Be it known by this, that it has been in our consideration of late about settling of White People on the Indian Lands, And we have concluded that it is a thing which ought not to be, & a thing that will not be allowed by us, that of Renting or giving Leases for said Lands, hereafter, no, not by the proprietors themselves without the consent of the rest much more by those who has no Claim or Rite here ...

We have come upon those resolutions we hope for our better living in friendship among one another, it may be that there is some which does not like white people for their Neighbours, for fear of their not agreeing as they ought to do. it might be about there children or about something they have about them we know not what, Again it may be the white Man may do something either upon Land, Timber or something else which some one of the proprietors would not like & from thence would come great deal of Disquietness, & many other ways which may plainly be seen into, by those that have any sense or reason—

We are exceeding glad when we see we are like to live in Quietness among one another without giving any offence to one another, & this of keeping white people from among us will be a great step towards it, & for this reason we intend to stand by or rather stand Hand in hand against any coming on the Indian Lands.

— Joseph Micty, Bartholomew Calvin, Jacob Skekit, Robert Skikkit, Derrick Quaquiuse, Benjamin Nicholus, Mary Calvin, Hezekiah Calvin

Displacement to Stockbridge, New York

In 1796, the Oneidas of Stockbridge invited Brotherton's Lenape families to join their reservation. The initial Lenape response was negative; in 1798, Munsee Lenape community leaders Bartholomew Calvin, Jason Skekit, and 18 others signed a public statement of refusal to leave "our fine place in Jersey."[8][10]

However, in 1801, many of the Munsee Lenape families agreed to relocate to New Stockbridge, New York to join the Oneidas.[4][11] A few Munsee Lenapes stayed behind and assimilated with the white colonists.[8]

Displacement to Green Bay, Wisconsin

In 1822, the remaining families were forcefully displaced over 900 miles' travel away[12] to Green Bay, Wisconsin.[4]

References

- ↑ U.S. Geological Survey Geographic Names Information System: Indian Mills, New Jersey

- ↑ Locality Search, State of New Jersey. Accessed March 14, 2015.

- 1 2 3 Thomas, JD (August 29, 2013). "The Colonies' First and New Jersey's Only Indian Reservation". Accessible Archives Inc. Retrieved July 12, 2018.

- 1 2 3 4 Barbara, Hoskins; Foster, Caroline; Roberts, Dorothea; Foster, Gladys (1960). Washington Valley, an informal history. Edward Brothers. OCLC 28817174.

- ↑ "The Brotherton Indians of New Jersey, 1780 | Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History". www.gilderlehrman.org. Retrieved April 21, 2022.

- ↑ Kephart, Bill & Mary (November 7, 2010). "The Kepharts: Cohawkin, Raccoon Creek, Narraticon all names left by Lenni-Lenape in Gloucester County". NJ.com. Retrieved July 12, 2018.

In 1758, the Colonial Legislature purchased land in Burlington County for a reservation. It was the first Indian Reservation in America and was called Edgepelick. Governor Bernard called it Brotherton. Today the area is known as Indian Mills. In 1801, an act was passed directing the sale of Brotherton, with the proceeds used to send the remaining Lenni-Lenape to the Stockbridge Reservation near Oneida, N.Y. There they formed a settlement called Statesburg.

7 November 2010 - ↑ "Collection: New Jersey Association for helping the Indians records | Archives & Manuscripts". archives.tricolib.brynmawr.edu. Retrieved April 21, 2022.

- 1 2 3 4 "The Brotherton Indians of New Jersey, 1780 | Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History". www.gilderlehrman.org. Retrieved April 21, 2022.

- ↑ Micty, Joseph (January 6, 1780). "Statement opposing white settlement on Indian land in Brotherton, New Jersey" (PDF). The Gilder Lehrman Collection.

- ↑ "[Brotherton statement of refusal to leave New Jersey] | Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History". www.gilderlehrman.org. Retrieved April 21, 2022.

- ↑ "New Stockbridge Tribe". collections.dartmouth.edu. Retrieved April 21, 2022.

- ↑ "Green Bay to Stockbridge". Green Bay to Stockbridge. Retrieved April 21, 2022.