| |

| Industry | Shipping |

|---|---|

| Founded | 1966 |

| Defunct | 1981 |

| Fate | Merged with Seaspeed |

| Successor | Hoverspeed |

| Headquarters | , |

Area served | English Channel |

Key people | J.A. Hodgson, Managing Director |

| Services | Passenger transportation |

Number of employees | 623 (Permanent); 229 (Seasonal); 1980 |

| Parent | Brostroms Rederi AB |

Hoverlloyd operated a cross-Channel hovercraft service between Ramsgate, England and Calais, France.

Originally registered as Cross-Channel Hover Services Ltd in 1965, the company was renamed Hoverlloyd the following year. It was initially owned by a partnership between the Swedish Lloyd and the Swedish American Line shipping companies. On 6 April 1966, Hoverlloyd commenced operations from Ramsgate Harbour to Calais Harbour, operated the SR.N6 hovercraft while awaiting the completion of the considerably larger SR.N4 ferries. In addition to competing with traditional ferries, it had a fierce rivalry with hovercraft operator Seaspeed, which also operated SR.N4s on the cross-Channel route. In 1969, in conjunction with the arrival of the first SR.N4s, Hoverlloyd re-positioned its services to run between purpose-built hoverports.

The 1970s were years of optimism and growth for Hoverlloyd. Following initial difficulties, the company's fleet achieved a very high reliability record, having consistently operated more than 98 per cent of scheduled crossings while maintaining an unblemished safety record throughout the firm's existence. Hoverlloyd possessed excellent operational bases, a hovercraft-friendly route, a fleet capable of generating returns on investment, and good quality staff. By 1980, it was operating a fleet of four SR.N4s. In 1981, in response to increasing operating costs and intensifying competition, Hoverlloyd opted to merge with its long-term rival Seaspeed to form Hoverspeed.

Background and formation

During the late 1950s and early 1960s, British inventor Sir Christopher Cockerell had, in cooperation with British aerospace manufacturer Saunders-Roe, developed a pioneering new form of transportation, embodied in the form of the experimental SR.N1 vehicle, which became widely known as the hovercraft.[1] British manufacturer Saunders-Roe proceeded with work on various hovercraft designs, successfully developing multiple commercially viable vehicles in the mid-1960s. These included the SR.N4, a large cross-Channel ferry capable of seating up to 418 passengers along with 60 cars, and the SR.N5, the first commercially active hovercraft.[2]

The origins of Hoverlloyd can be traced back to a decision made by Swedish Lloyd shipping company in 1964 to investigate the possibility of operating a hovercraft service, which was then a pioneering and untried concept to any business.[3] The company soon formed a partnership with Swedish American Line, owned by Brostroms Rederi AB; both companies were keen to take the lead in what they viewed as an emerging and potentially lucrative market, having identified the heavily trafficked ferry services between the ports of Dover, UK, and Calais, France, as being ripe for disruption by the new hovercraft technology.[4]

Accordingly, the two firms jointly formed a new venture to address this market; this entity was originally named the Cross-Channel Hover Services Ltd, which was registered as a British company in 1965. The company was renamed to Hoverlloyd Ltd during the following year. Despite being largely regarded as being a single company, Hoverlloyd was in fact structured as two separate companies, one being based in France and the other in the UK.[5]

Airline Industry Culture

Unlike its rival, Seaspeed, Hoverlloyd recruited its sales and traffic personnel from the airline industry. The company was fortunate to hire the majority of its staff following the collapse of British Eagle in 1968. As such, the company operated more like an airline than a shipping company. Crew uniforms were sourced from the British Airways depot at London Gatwick. The traffic manual was based on the defunct airline's standard operating procedures. Moreover, tickets and boarding passes were documents based on airline industry format.[6]

Early operations

Ramsgate to Calais Route

Prior to commencing operations, the company exercised great attention in the selection of the most advantageous route, as well as the optimal sites to establish bases at. It decided to focus its attention on the Ramsgate to Calais route, having identified this as possessing the perfect set of circumstances for a successful hovercraft route. Favourable factors at Pegwell Bay included a 10 miles out shelter from prevailing weather conditions when near the Goodwin Sands, while day-to-day timings could be adjusted to take advantage of both tides and winds. There was no need to negotiate the stone-walled entrances which would have been the case with Dover Harbour either.[7]

Least to say, the company was severely restricted as to its course of action. Folkestone was naturally out of the question because the harbour was run by British Rail. Moreover, there was no welcome from Dover to secure a hold lease at the Eastern Docks with British Rail members on the harbour board exercising their vetoes. This left Ramsgate as the only viable option. Hoverlloyd commenced operations from Ramsgate Harbour to Calais Harbour on 6 April 1966.[7]

Initially, the company operated an interim fleet of SR.N6 hovercraft; services with these craft were passenger-only. Upon the launch of these services, it was publicly acknowledged that the SR.N6 was unable to compete with conventional ferries in terms of ticket price alone.[8] Despite this, hovercraft services held a competitive advantage in that they were significantly faster than these ferries, being able to rapidly traverse the English Channel with 'flight times' reportedly as low as 22 minutes.[8]

In addition to the provision of an initial revenue stream, SR.N6 operations provided valuable operating experience, guiding future routing decisions via knowledge of dominant weather conditions and such factors. These experiences were transferable to the company's larger hovercraft, however their vast difference in size and manoeuvrability somewhat dulled the value of such experiences.[9] In particular, while the Goodwin Sands were historically avoided as a threat to conventional vessels, the hovercraft could easily operate in their vicinity without hindrance, free of other traffic concerns.[10]

Between 1969 and 1977, Hoverlloyd took delivery of a total of four significantly larger SR.N4 hovercraft, capable of carrying 30 vehicles and 254 passengers; the type quickly replaced the SR.N6s on the Ramsgate-Calais link. The first craft was purchased at a cost of £1.2 million from the British Hovercraft Corporation.[11] The SR.N4s were given the names Sure, Swift, Sir Christopher, and The Prince of Wales respectively.

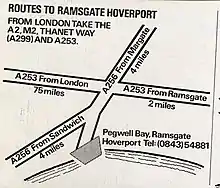

In 1969, in conjunction with the arrival of the first SR.N4s, Hoverlloyd re-positioned its services to run between purpose-built hoverports. Pegwell Bay, near Ramsgate, hosted one newly built hoverport, while a similar facility just east of Calais harbour was shared between Hoverlloyd and its rival Seaspeed.[3] The development of suitable hoverports for the SR.N4 fleet had not come cheaply; Hoverlloyd incurred a significant cost to develop suitable infrastructure to facilitate its future operations, and thus commenced service after a relatively short prototype testing period.[12]

Early on, hovercraft operations proved to be prone to disruption and abrupt cancellations on the part of adverse weather conditions, which were unfortunately common to the Channel.[13] However, the impact of unfavourable conditions was eased over time by various modifications and improvements to the craft, such as increasingly durable rubber 'skirts', which had sustained damage from rough seas as well as ordinary wear-and-tear.[14]

Other initial issues, such as hydraulic unreliability and equipment failures, were also partially attributable to worker unfamiliarity with the craft.[12] A side effect of the hovercraft's high speed was a relatively bumpy ride.[15] Benefits of the hovercraft configuration included an unmatched turnaround time, partly enabled by the ability to disembark/embark cars at both ends of the craft, whilst simultaneously facilitating the movement of foot passengers via two main exits on the port and starboard cabins. The capabilities of its SR.N4s were significantly augmented in 1973 with the delivery of the Mk.II modifications.[16]

Competition with Seaspeed

Hoverlloyd was not the only hovercraft operator that decided to move on the cross-Channel market at the time; a rival company Seaspeed, owned by British Rail, was established and launched its own competing route between Calais and Dover. The two firms would compete with one another, as well as incumbent ferry operators, for market share throughout Hoverlloyd's existence.[15]

Heyday of operations

Hoverlloyd principally concentrated on the Ramsgate to Calais link throughout the life of the company. By 1979, a typical day's operation at Pegwell Bay Hoverport involved 27 daily departures, starting as early as 6:00am and ending late in the evening; that year, 1.25 million passengers travelled by Hoverlloyd services on this route.[3]

Furthermore, rival Seaspeed proved incapable of matching the reliability record of Hoverlloyd, which consistently operated over 98 per cent of scheduled crossings while maintaining an unblemished safety record throughout the firm's existence.[17]

In 1975, Hoverlloyd was reportedly operating its fleet at near-maximum capability throughout the peak season; this feat was successfully repeated during the following year and again the year after that. According to Paine and Syms, the company had an attitude of optimism and confidence at the time, as it continued to expand its operations.[18]

Sale to Brostroms Rederi AB

From initial losses of -£250,000 in 1968 and -£164,000 in 1969, Hoverlloyd returned a profit in 1972 and continued to do so until 1980 with profit margins of 10.5% in 1976, 10.0% in 1977 and 7.0% in 1978.[19] In 1976, with the company financially attractive, Brostroms Rederi AB decided to purchase Swedish Lloyd's stake in Hoverlloyd, becoming the sole owner of the entire operation.[20] Hoverlloyd would remain a wholly owned subsidiary of Brostroms Rederi AB until 1981.[21]

| Year | Turnover (£) | Profit/Loss (£) | Margin of Profit (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1976 | £10,501,000 | £1,107,000 | 10.5% |

| 1977 | £14,628,000 | £1,470,000 | 10.0% |

| 1978 | £16,728,000 | £1,183,000 | 7.0% |

| 1979 | £18,621,000 | £243,000 | 1.3% |

| 1980 | £17,242,000 | (-£686,000) | (-3.9%) |

According to authors Robin Paine and Roger Syms, Hoverlloyd possessed excellent operational bases, a hovercraft-friendly route, a fleet capable of generating returns on investment, and good quality staff.[7] Specifically, the company's customer-facing staff were strictly drilled and trained for their roles; stewardesses were required to maintain a high level of presentability, being compelled to wear their hair up, wear white gloves, and instructed how to apply their makeup.

Presentability and enthusiasm were considered to be competitive advantages over the rival Seaspeed's services.[15] Staff typically displayed a high level of loyalty to the company, an outcome which has been attributed to the company's amenable management style, which positively affected industrial relations.[23] Crew received extensive safety training, including weekly drills, so that they were able to readily respond to a wide range of emergency situations.[24]

Duty Free Sales

Hoverlloyd sold various duty-free goods on board their SR.N4s during the cross-Channel transit. These sales comprising a meaningful portion of the service's overall revenue; thus the company strongly emphasised the importance of onboard sales amongst their staff.[8] For example, in 1979, 30% of operating profits was accountable to duty-free sales.[25]

Coach Services

For many years, Hoverlloyd operated a successful express coach/hovercraft/coach service from London to a number of near European cities with fares which were considerably cheaper than comparable air fares that were available at the time; the most frequent service was London - Paris, while London - Brussels had fewer departures. In 1978, these were the only two destinations; London - Amsterdam was added during 1979.

On the UK side, the coaches were operated with Hoverlloyd liveried coaches provided by Evan Evans Ltd - at that time a subsidiary of Wallace Arnold Tours of Leeds. Coaches did not cross the channel, although the hovercraft was able to readily accommodate standard-height coaches with luggage space at the rear.

Hoverlloyd examined various additional coach services; while considerable exploration of launching services reaching into the German market was performed, licensing issues allegedly proved to be complex enough to prevent further expansion.[26]

Further Sea Routes

Hoverlloyd held ambitions to launch scheduled services to various other destinations throughout its life. Tentative plans to operate from Southend-on Sea to Ostend in Belgium were mooted but ultimately never progressed.[27]

Economics of large hovercraft operation

Rising oil prices

Each SR.N4 was powered by an arrangement of four Bristol Proteus gas turbine engines; while these were marinised and proved to be one of the hovercraft's more reliable systems, they were relatively fuel-hungry, consuming significant amounts of aviation-grade kerosene. As the worldwide oil crisis of the 1970s caused fuel prices to rise sharply, the operation of the SR.N4 became increasingly uneconomic, especially in comparison to slower, diesel-powered ferries.

Non-Freight Business

Unlike ferry operators, Hoverlloyd was wholly reliant on non-freight business (cars and foot passengers), and unable to offset a decline in demand with other forms of business activities.

Debt Servicing

Hoverlloyd was a highly leveraged company with debt accounting for one-third of operating profits in 1976 and 1977 to two-fifths in 1978, three-fifths in 1979 and four-fifths in 1980.[28]

Supply Chain

The closure of the British Hovercraft Corporation restricted support options, meaning that maintenance of the craft became more costly over time, and that neither like-for-like replacements or improved successor hovercraft were likely to be developed. Thus, Sure was taken out of service in 1983 and cannibalised for parts to keep the rest of the fleet operating.

These combined factors gradually worsened Hoverlloyd's balance sheet as time progressed and demanded economies of scale, and consolidation of operations.

Merger and rationalisation

By 1980, in the midst of a global recession, it was obvious that cross-Channel hovercraft operation could only continue economically if the two operating companies merged, with consequent rationalisation.

Hoverlloyd's owners were adamant: If the merger did not take place, operations would cease. Hoverlloyd had already been put for sale in October 1979 as a going concern but had not attracted interest. Finally, in 1981, Hoverlloyd and Seaspeed merged to create the combined Hoverspeed.[29][20]

Hoverlloyd services under the Hoverspeed banner from Ramsgate were subsequently withdrawn after the 1982 season and the four ex-Hoverlloyd craft were thereafter based at Dover and gradually withdrawn from service between 1983 and 1993 to be used for spare parts for Hoverspeed's remaining SR.N4 fleet.[30]

Ramsgate hoverport

For a time, the hoverport at Pegwell Bay was used as an administrative and engineering base by Hoverspeed after all passenger services had ceased. However, the former activity moved to Dover in October 1985 and the latter (mainly used for craft overhauls) in late December 1987 with the buildings demolished in 1992.[3] The hovercraft pad, car-marshalling area and approach road are the sole identifiable features that remain at the site.[15]

Fleet

Built as Mk.I unless specified otherwise.

- 01 – GH-2004 Swift, Hoverlloyd – converted to Mk.II specification for February 1973, broken up in 2004 at the Hovercraft Museum.

- 02 – GH-2005 Sure 1968, Hoverlloyd – converted to Mk.II specification in 1972, broken up in 1983 for spares

- 03 – GH-2008 Sir Christopher 1972, Hoverlloyd – converted to Mk.II specification in 1974, broken up 1998 for spares

- 04 – GH-2054 The Prince of Wales, Hoverlloyd – built as Mk.II, scrapped in 1993 following an electrical fire

All four ex-Hoverlloyd craft were eventually broken up and none remains.

In Popular Culture

Film Industry

The SR.N4 GH-2005 Sure starred in La Gifle with a very young Isabelle Adjani and in The Black Windmill, starring Michael Caine, both released in 1974. The SR.N4 is also featured in the 1980 film Hopscotch starring Walter Matthau and Glenda Jackson.

References

Citations

- ↑ Paine and Syms 2012, p. 82.

- ↑ Paine and Syms 2012, pp. 238, 595.

- 1 2 3 4 Paine and Syms 2012, p. 14.

- ↑ Paine and Syms 2012, p. 478.

- ↑ Paine and Syms 2012, p. 467.

- ↑ Robin Paine, Roger Syms (2012). On a Cushion of Air. Robin Paine and Roger Syms. p. 447. ISBN 9780956897800.

- 1 2 3 Paine and Syms 2012, pp. 474.

- 1 2 3 "Hovercraft Facts". 1966: Hovercraft deal opens show. BBC. 15 June 1966. Retrieved 9 April 2010.

- ↑ Paine and Syms 2012, pp. 481-483.

- ↑ Paine and Syms 2012, pp. 484-491.

- ↑ Paine and Syms 2012, p. 596.

- 1 2 Paine and Syms 2012, p. 505.

- ↑ Paine and Syms 2012, p. 479.

- ↑ Paine and Syms 2012, pp. 521-523, 529.

- 1 2 3 4 "Hovercraft". BBC. 6 March 2006.

- ↑ Paine and Syms 2012, pp. 474, 531-540.

- ↑ Paine and Syms 2012, p. 481.

- ↑ Paine and Syms 2012, pp. 561-563.

- ↑ British Rail Hovercraft Ltd and Hoverlloyd Ltd: Proposed Merger. London: HMSO Government. 1981. p. 29.

- 1 2 "Merger of British Rail Hovercraft Ltd and Hoverlloyd Ltd to form Hoverspeed UK Ltd". The National Archives, Kew. 1 November 1981.

- ↑ Paine and Syms 2012, pp. 614-617.

- ↑ British Rail Hovercraft Ltd and Hoverlloyd Ltd: Proposed Merger. London: HMSO Government. 1981. p. 29.

- ↑ Paine and Syms 2012, pp. 467-469.

- ↑ Paine and Syms 2012, pp. 551-553.

- ↑ Robin Paine, Roger Syms (2012). On a Cushion of Air. Robin Paine and Roger Sym. p. 463. ISBN 9780956897800.

- ↑ Paine and Syms 2012, pp. 465-467.

- ↑ "Hovering on the Brink". New Scientist. 67: 84. 1975.

- ↑ William, Moses (MBE) (2011). The Commercial and Technical Evolution of the Ferry Industry 1948-1987. London: University of Greenwich. p. 207.

- ↑ Merger approved Modern Railways issue 395 August 1981 page 343

- ↑ Paine and Syms 2012, pp. 616-626.

Bibliography

- Paine, Robin and Roger Syms. "On a Cushion of Air." Robin Paine, 2012. ISBN 0-95689-780-0.