The History of Asturias includes everything from when the Paleolithic tribes settled in the Cantabrian Coast to the modern post-industrial society of today. On the etymology of the term "Asturias", some think that its origin can be traced back to the name of the Astura river (today the Esla river), whose inhabitants were called "astures" by the Roman authors.[1]

Prehistory

Paleolithic

Asturias was inhabited by humans since the Lower Paleolithic (100,000 years ago), from the Acheulean to the Mousterian. There are rock paintings that date back 30,000 years and correspond to the Solutrean, Magdalenian, and Aurignacian cultures of the Upper Paleolithic and typical of both the peoples of the Cantabrian Mountains and Southern France.[1]

From the sites known to date, it is believed that the first settlers of Asturias inhabited the Cantabrian coast and the river valleys: the Pindal caves (Ribadedeva), Posada, Tito Bustillo (Ribadesella), Buxu (Cangas de Onís), Peña de Candamo (Candamo), and Covaciella (Cabrales).[1]

Mesolithic: Asturian culture

An original culture emerged during the Mesolithic, the Asturian, typical of eastern Asturias and western Cantabria. These settlements could be found in the entrance of caves close to the sea or under shelters, generally near the coast, although they were also found in inland Cantabrian mountains.[1]

Neolithic

Evidence of the Asturian Neolithic includes the thirty dolmens of the prehistoric necropolis of Mount Areo, between Carreño and Gijón, 5,000 years old, as well as burial mounds and the Idol of Peña Tú (Llanes). At some point the earlier cultures abandoned the caves and mastered agriculture and animal husbandry.[1]

According to Avienius in his description of the coasts of western Europe, the people who originally inhabited the north of the peninsula and the Atlantic coast as far as Brittany were the Oestrimnios. They were descendants of the first inhabitants who were pre-Indo-European and non-Celtic Indo-European. These groups were later displaced by others that formed the Ofiusa (name given to the entire north of the peninsula): Cempsos, Sejes, Ligus, and Draganos. The Draganos, of Celtic origin, occupied present-day Asturias.[1]

Ancient history

Castro culture

The period from the abandonment of the caves until almost the Romanization is quite unknown. Greek or Latin authors speak of barbaric and battle-hardened tribes that lived in the jungles and mountains. Roman writers such as Pliny the Elder and Pomponius Mela, and Greek writers like Strabo, mention two main astures tribes separated by the Cantabrian Mountains: the Augustanos (with their capital in Asturica, present-day Astorga, whose domains reached the Duero river) and the Transmontanos (that spread between the Sella river and the Navia river). However, these divisions are now understood to be the product of Roman practicality in establishing administrative and police systems, and not as a reflection of accurate indigenous identities.[2]

There is also written proof of the hard fights between Astures and Cantabri along the Sella riverbed. They illustrate the roughness and bravery of both peoples and their resistance to Roman domination.[2]

Evidence of human presence in Asturias during this period includes the castros. Among them, the Castro of Coaña is an Asturian settlement built at the beginning of our era near the capital of the Coaña council. It lost importance from the 3rd century onwards and has been related with gold mining in the Navia river.[2] Other notable castros include Pendía (Boal), Chao Samartín (Grandas de Salime), San Chuis (Allande), Os Castros (Taramundi), Cabo Blanco (El Franco), La Sobia, and La Cogollina (Teverga), Campa Torres (Gijón), Caravia,[3] and about 300 others.[4]

Romanization

By the end of the 1st century BC, the Romans wanted to complete the conquest of the entire Iberian Peninsula. Only the northern peoples, Astures and Cantabri, weren't under Roman control at the time. The main imperial interest in this region was the underground gold of the northwestern peninsular area,[6] The main imperial interest in this region was the underground gold of the northwestern peninsular area, known to the Romans from the expedition against Gallaecia by Brutus. Additionally, the young Emperor Augustus needed a victory to glorify his position.[7] In 29 BC, the Vaccei, Astures, and Cantabri got together in their fight against the Romans, who concentrated all their military power in the north of the peninsula. Caesar Augustus had to personally lead his troops.[8]

Augustus carefully planned the war, creating extensive supply networks[9] for his eight mobilized legions: I Augusta, II Augusta, IV Macedonica, V Alaudae, VI Victrix, IX Hispanensis, X Gemina, and XX Valeria Victrix, totaling around 50,000 men.[10] The complex Asturian geography and the fierce Asturian resistance, organized through guerrilla warfare,[11] prolonged the Roman invasion until 19 BC. Most of the war occurred between 26 and 22 BC, with several battles, such as the siege of Mount Medulio.

According to Greco-Latin sources,[12] in 25 BC, the Astures crossed the mountains of the Cantabrian coast and camped near the Astura river (now known as the Esla river). They divided their forces into three columns to attack three Roman camps. Had it not been for the treachery of Brigaecium city, which alerted the Romans thus giving them time to reorganize and repel the attack, the Asturians would have overwhelmed the troops of General Publius Carisius. After this defeat, the Astures took refuge in the oppidum of Lancia, which was attacked and occupied by the legate of Lusitania.

However, this did not mark the end of Asturian resistance. The Romans had to deal with successive rebellions that periodically arose because of treatment received from the invader or the increase in taxes. There were several rebellions in 24 BC, 22 BC and a last one in 19 BC, which was the most severely repressed. Augustus, wanting a quick pacification, left command of his troops to his best strategist: Agrippa.[6]

Romanization began militarily, securing the mountainous territory filled with castros, through camps like La Carisa.[13] Military control allowed for a reliable extraction of precious minerals, especially in El Bierzo through the mines of Las Médulas, located in present-day León. A large number of Astures were recruited into the Roman army to undertake defensive campaigns on the borders of the Roman Empire.[14]

Early Middle Ages

Visigothic monarchy

The fall and disintegration of the Roman Empire, which seemed to have not exerted much influence on the Asturian territory, occurred in the 5th century. In the 6th century, the invasion of the Iberian Peninsula by the Visigoths and Suebi was rejected by the Astures, thus remaining outside of the cultural influence of Germanic peoples.

Primitive Christianity was established in Asturias between the 5th and 8th centuries.

Asturian monarchy (718-910)

When the Muslims won the battle of Guadalete (711) against the Visigothic Kingdom of Toledo, the Christians of Toledo fled to seek refuge in Asturias. It was then that the relics currently kept in the Holy Chamber of the Cathedral were brought to Asturias. They were first kept in Monsacro (Mounts of Morcín) and later in Oviedo. This region never underwent intense Arabization, since the Muslim occupations were occasional and had more of a razzia character.

In 716, the first rebellion against Muslim rule occurred in Asturias, led by Don Pelagius (probably of noble origin). This rebellion was suppressed, and Pelagius was arrested and imprisoned.

Pelagius managed to escape from Córdoba in 717, reaching the Piloña River in 718, and that same year, he became the leader of the Astures, after persuading and convincing the Asturian people of the need to unite their forces against "the common enemy." In May 722, a second confrontation took place in the Battle of Covadonga against the Arab general Munuza. This was more of a guerrilla victory than a military one. In order to consolidate the triumph, Pelagius proclaimed himself king in Cangas de Onís, founding the Kingdom of Asturias.

As a result of several splits and regroupings, the Asturian monarchy would give way in the following centuries to the Kingdoms of León, Galicia, Castile, and Portugal. From then until 1492, the Iberian Peninsula was divided into a Muslim part and a Christian part.

During Fruela's reign, the capital was moved to Oviedo. There, the abbot Maximus and his nephew Fromestano built a Benedictine cenobium over the ruins of a Roman castro. This castro, which in the times of Augustus protected the nearby city of Lucus Asturum (probably in the Lugones area), was located on the top of Obetao hill. Alfonso II the Chaste fortified the city, built the primitive basilica of San Salvador, and the basilica of San Julián de los Prados.

Significant examples of Asturian pre-Romanesque art were built during the 9th century (between the reigns of Ramiro I and Alfonso III the Great) such as San Miguel de Lillo, Santa María del Naranco, the church of San Salvador de Valdediós, and Santa Cristina de Lena.

The Kingdom of Asturias was divided after the death of King Alfonso III the Great, who distributed his dominions among three of his five sons. These dominions included (in addition to Asturias) the counties of León, Castile, Álava, Galicia, and Portugal (which at that time was only the southern border of Galicia). García inherited the first two counties, founding the Kingdom of León. Ordoño II inherited Galicia and Portugal, while Fruela II first inherited Asturias and then the Kingdom of León from his brother García I, who had no heirs.

Late Middle Ages and Early modern period

After the merging of the two kingdoms, Asturias and León, the capital moved to the well-fortified Roman city of León. As a result, Asturias became a remote and difficult-to-access region, only visited when pilgrims on the Camino de Santiago detoured to Oviedo to visit the relics of the cathedral.

Secessionist movements

The loss of this influence led to several secessionist movements; one of the most significant occurred in the 12th century with the uprising of Count Gonzalo Peláez against King Alfonso VII and Urraca, who ruled Asturias on behalf of the King.[15]

Origin of the Principality of Asturias

In 1388, through the Treaty of Bayonne, John I of Trastámara and John of Gaunt put an end to their disputes over the throne of Castile by arranging the marriage of their children, Henry III of Castile and Catherine of Lancaster, a ceremony that took place in the Cathedral of Palencia. Both were granted the title of Princes of Asturias, thus establishing the Principality of Asturias and the title that the heir to the Crown would hold in the future. Additionally, this title was linked to a series of territories that, due to their isolation, were a constant source of rebellion.[16]

In the early days of the institution, the territory of Asturias belonged to the prince as his patrimony, and he could appoint judges, mayors, among other people to govern on his behalf. This situation changed with the Catholic Monarchs, who reduced the title to an honorary condition.

Asturias in the Castilian Civil War: 15th century

Asturias played an important role in the uprising that King Alfonso V of Portugal initiated in favor of the succession rights of his niece Joanna and against Isabella the Catholic, following the death of King Henry IV. Alfonso V relied on discontented Castilian nobles, while Isabella was supported by troops sent from Asturias and Vizcaya.

The ancient General Junta of the Principality of Asturias was established during this period.[17]

Baroque Asturias: 17th century

.jpg.webp)

In the 17th century, Asturias faced a precarious situation beginning with an epidemic that started in 1598 and would ultimately claim 20% of the population.[18] There was another pandemic in 1693.[19] Despite these demographic shocks, Asturian population had an important growth, especially on the coast and in the valleys.[20] Economically, the introduction of maize into Asturian agriculture, favored by the region's rainy climate, benefited rural subsistence economies.[21] Bishop Fernando Valdés Salas of Salas founded the University of Oviedo, which began operating in 1608,[22] and the construction of Oviedo Cathedral was completed during this period.

Late modern period

Asturias during the War of Independence

When Napoleon Bonaparte invaded Spain in 1808 with the support of the Afrancesados, the War of Independence began. On May 9, the General Junta of the Principality of Asturias chose to disobey the orders coming from Madrid, where the executions of May 2 had taken place, causing tension among the Asturians and serving as the reason for disobedience. However, on May 13, the Junta panicked and decided to heed French orders. In response, on May 25, 1808, a popular uprising declares the people of Asturias as sovereign in the Chapter house of Oviedo Cathedral. They also seized several points in Oviedo, such as the La Vega arms factory, and established a new governing body: the Supreme Junta.[23] They gathered an army of over 20,000 men from different councils soon after, declared war on France, sent a delegation to King George III, and set the precedent for the Supreme Central Junta, coordinator of the different Supreme Juntas of the Spanish territory.[24]

Asturias during the Carlist Wars

Asturias was the scene of several battles during the First Carlist War (1833-1839), especially Oviedo, which was taken by General Gómez in the summer of 1835 after crossing the Tarna pass with a Carlist detachment of 2,800 men. However, after 3 days, he had to abandon the city due to the arrival of Espartero's troops.[25] This event is likely the origin of the gastronomic tradition in Oviedo known as "Día del Desarme" (day of disarmament).[26] In the eastern part of Asturias, in September 1836, another Carlist offensive took place led by General Sanz, who captured Llanes and Infiesto. He attempted to besiege Oviedo but gave up and retreated.[25] In Gijón, a defensive wall was built starting in 1837 to protect the town, but it was demolished in the 1880s to make way for the widening of Gijón.[27]

During the Third Carlist War, between 1873 and 1876, the Carlists were better organized although they were still defeated. Notably, in 1874, the Carlist leader José Faes died in Mieres, the main Carlist stronghold.[25]

Enlightened Asturias

Mentality

Asturias experienced centuries of isolation. There was a lack of public education, which was only for the privileged classes. The creation of the University of Oviedo in 1608 did not solve the problem because it was disconnected from the changes in higher education that had been happening in other places.[28]

Even during the 18th century, although the church ceded its traditional hegemony over cultural and educational initiatives, the changes remained subtle. Additionally, the press (journals, newspapers, essays, etc.), which was crucial in other regions, did not have a dynamic impact in Asturias due to the absence of printing industries in the area. As a result, enlightened culture only reached very small groups.[28]

The enlightened minority tried to introduce their ideas through the exercise of power (enlightened despotism). In Asturias, this minority included small sectors of the landowning nobility and the clergy, meaning small and elitist circles of society that would gather in salons, social gatherings, and conferences and maintain contact with European intellectuals.[28]

Asturias contributed important names to the Spanish Enlightenment. Among them Father Feijoo (1676-1764), originally from Ourense, a precursor of the generation. Other prominent figures included the military treatise writer Álvaro Navia Osorio (1684-1732), Marquess of Santa Cruz; the Catalan physician Gaspar Casal (1680-1759); the economists and politicians José del Campillo y Cossío (1693-1743) and Flórez Estrada (1765-1853); the jurist and writer Martínez Marina (1754-1833); the historian Canga Arguelles (1771-1842); the politicians Count of Toreno (1727-1805) and Count of Campomanes (1723-1802); and the politician, economist, writer, historian, philosopher, and essayist Gaspar Melchor de Jovellanos (1744-1811).[28]

Two great enlightened men of this period are worth mentioning:

- Benito Jerónimo Feijoo, a Benedictine monk born in Ourense who undertook research and study in various fields at the San Vicente Monastery. He was as a professor at the university in Oviedo from 1709 to 1764.[29]

- Gaspar Melchor de Jovellanos is the most representative figure of the Spanish Enlightenment movement. In addition to holding political positions such as Minister of Grace and Justice (dismissed due to his reformist vision), he made important theoretical and practical contributions in economics, agriculture, education, and theater and public spectacles. Jovellanos' concern for his homeland led him to undertake numerous projects in the region, such as the creation in 1794 of Spain's first center to training experts in navigation and mineralogy; the Institute of Nautics and Mineralogy. He also planned a road to Castile through Pajares, the coal road, and promoted mining and industrial ventures in Asturias.[30]

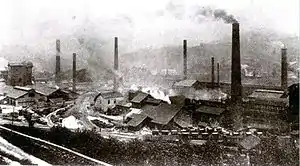

Industrialization between 1852 and 1934

In 1852, the first section of the first railway line in Asturias (the Langreo Railway, between Gijón and Langreo) was officially opened. This line, the third in Spain, transported the coal extracted from the Nalón basin to the port of Gijón.[31] In 1874, a broad-gauge railway opened, the León-Gijón railway, which was linked to the Meseta from 1884 through the Pajares incline.[32] It had various branches; one to Avilés[33] was inaugurated in 1890, and another to El Entrego in 1894.[34] The coal was either consumed internally or exported from Asturias through ports, especially through the port of El Musel, inaugurated in 1907.[35]

Between 1843 and 1849, the Asturian Mining Company operated in the municipality of Mieres.[36] It would be the predecessor of the three major steelworks of the century: the Mieres factory, founded in 1879 in Mieres;[37] the Felguera factory, dating back to 1857 and the most important;[38] and the Moreda factory in Gijón, which started its activity in 1880.[39]

However, the main industry in Asturias was coal mining, developed in the Mining Basins, located in the center of Asturias. Originated mainly in the mid-19th century,[40] it experienced its golden age after 1914 due to Spain's neutrality in the Great War and the protectionism of successive governments.[41]

Asturias preserves a large number of industrial heritage elements, especially a significant number of headframes throughout the region.[42]

Asturian labor movement 1890-1934

The Asturian working class became organized and in the 1890s, the first socialist groups appeared in Oviedo and Gijón, and somewhat later in La Felguera and Mieres. In 1898, the first anarchist association emerged, and in 1881, the first workers' strike in Asturias took place in the Llascaras and La Moral mines in Langreo.[43] It wasn't until 1901 that a large-scale strike occurred, with workers from El Musel port and supported by those from the Moreda factory, but it was thwarted by pressure from the employers. In 1906, the Mieres factory started another unsuccessful strike. In 1910, Manuel Llaneza founded the Miners' Union (SOMA, in Spanish Sindicato de los Obreros Mineros de Asturias), which became the most powerful union in the region.[44] To counter it, the Patronal Association of Asturian Miners, promoted by the anti-worker Marquis of Comillas, proposed Catholic trade unions, which were not very popular.[43]

Meanwhile, the CNT (Confederación Nacional del Trabajo) became established in the region's largest industry, Duro Felguera, owners of the Felguera Factory, and in 1912, they initiated a tough strike. Despite their differences, SOMA supported the strikers, but their final immature agreements with the employers led to tensions between anarchists and socialists. Despite the productivity boom brought by Spain's situation in World War I, the quality of life was considerably reduced. As a result, Asturias actively participated in the 1917 Spanish general strike, lasting for two months and brutally repressed by the Civil Guard, led by General Burguete.[44]

In the following years, the Miners' Union achieved some labor improvements (reduced working hours, wage increases, etc.), and Manuel Llaneza requested the government to implement protectionist measures for the coal sector, which caused discontent among the members that viewed it as a move towards bourgeois interests, leading to a period of internal conflicts that resulted in Llaneza's removal from the Union's leadership in 1921. Additionally, some members joined the Communist Party of Spain PCE (Partido Comunista de España).[44]

During Primo de Rivera's dictatorship, unionism, especially SOMA, adopted a lower profile and toned down its struggle, resulting in a precarious situation for the mining population.[44]

1934 October Revolution

The Asturian Revolution of 1934 was a workers' uprising part of the "revolutionary strike" and armed movement organized throughout Spain known as the October Revolution of 1934, which only took root in Asturias,[45] mainly because the CNT integrated into the Workers' Alliance proposed by the socialists of UGT (Unión General de Trabajadores) and PSOE (Partido Socialista Obrero Español), unlike the rest of Spain. Therefore, the social and political organization of the Asturian Commune (also known as the Asturian Revolution, due to its similarities with the Paris Commune of 1871)[46] aimed to establish a socialist regime in areas where socialists[47] (or communists) predominated - such as Mieres, where the "Socialist Republic" was proclaimed; or as in Sama of Langreo; or the libertarian communism where the anarcho-syndicalists of CNT predominated such as in Gijón and especially in La Felguera.[48] The uprising was harshly repressed by the radical-Cedist government of Alejandro Lerroux, against whom the insurrection was launched for including three ministers from the non-republican party CEDA in the government. The military operations were directed by General Franco from Madrid and involved the use of Moroccan colonial troops (the regulares of the Army of Africa) and the Legion from Spanish Morocco.[49]

The rebels took control of neighborhoods in Oviedo near the mining area and parts of the old town (San Lázaro, Campomanes, El Fontán, the Town Hall Square, and the Escandalera Square). The city's garrison, supported by some civilians, sought refuge in central areas of the city. After five days of fighting and with the approach of military reinforcements, the rebels withdrew after dynamiting the Cámara Santa of the cathedral, placing dynamite in the crypt of Santa Leocadia, and setting fire to the Campoamor Theater, the university, and several civilian buildings.

Following the left's electoral victory in February 1936, many of the prisoners from the uprising were granted amnesty, but in July 1936, several military commanders rose up against the democratically elected government.

Asturias during the Civil War (1936-1937)

.svg.png.webp)

During the Civil War, Asturias was isolated from the central government and had to form its own Administration. Oviedo was occupied by Colonel Aranda, of the Nationalists, who held it until the end with the help of the Escamplero and Naranco "passageway" (pasillo) through which supplies arrived. In Gijón, the CNT and FAI (Federación Anarquista Ibérica) governed, there was no currency and there was a certain lack of troop coordination between the front and the rear. On August 24, 1937, the Sovereign Council of Asturias and León was proclaimed in the city.[50] In October of the same year, several columns from the Villaviciosa front entered Gijón with little resistance and broke the siege of Oviedo.

The conflict lasted fifteen months, during which the main battles were fought around the capital, besieged by the militia, and on the borders of the region, Eo, Deva, and the Cantabrian coast, where the offensives of the national army tried to break the siege of the city.

Rebellion

After the coup, the Republican forces did not manage to dominate the entire province, despite being a majority, due to Colonel Aranda's support to the rebels, the head of the army in Oviedo.

Colonel Aranda delayed his decision to support the uprising until July 19, taking enough time to make the Republican authorities believe his loyalty to the regime and to gather the bulk of the military forces and Civil Guard in Oviedo for its defense. Meanwhile, Colonel Pinilla, encouraged by Aranda, rebelled the barracks in Gijón, starting the battle of the Simancas barracks.[51]

From July to October 1936

Both sides set their objectives: the Republican government aimed to quickly eliminate the rebel strongholds, while the Nationalists attempted to resist until the arrival of reinforcements from Galicia, known as the Galician column. In the government side, Committees emerged in the early days, trying to organize the militias.

The union of the Provincial Committee with the War Committee, member of the CNT and created in Gijón after the uprising, led to the formation of a new Provincial Committee, which soon became known as the Interprovincial Council of Asturias and León, based in Gijón and led by Belarmino Tomás. Members of the PSOE, PCE, Republican Left, and CNT also participated in this council.[50]

The rebels in the barracks of Gijón were defeated after 33 days of siege, despite the support provided by the cruiser Almirante Cervera, which bombarded the city from the coast. The Simancas barracks fell on August 21, still holding as Republican territory.[51] On the other hand, Oviedo was cut off and remained so until October 17, when Galician troops led by Colonel Tejeiro penetrated the city through a passageway opened from Grado through the Escamplero. The militia besieging the center failed to storm the last defenses despite the offensive carried out in the first days of this month.

From October 1936 to September 1937

The arrival of the Galician column to Oviedo sparked a crisis between anarchists and communists, leading to changes in some councilors and a shift in focus towards prioritizing military victory over social revolution.

To prevent the uncontrolled actions of the "Red terror" seen in previous periods, the Provincial People's Tribunal was created. Meanwhile, Oviedo received more aid through the opened passageway, improving the harsh living conditions of the besieged and increasing the number of prisoners and those subjected to repression, which had been relatively low in the early months. In February 1937, a new offensive was carried out with the participation of Asturian and Basque battalions with Soviet armament. It ends with a new failure in spite of managing to reach the city. In August 1937, a new Republican offensive was directed towards the "Pasillo de Grado" (passageway of Grado) in an attempt to cut off the material aid reaching the capital, but it was unsuccessful.

The fall of Biscay and the rapid rebel offensive towards Santander affected the battalions besieging Oviedo, as they were sent to Cantabria. Santander fell, causing fear among members of the Interprovincial Council.

On August 24, 1937, the Interprovincial Council became the Sovereign Council of Asturias and León, an independent political entity with its capital in Gijón. In this way, Asturias declared its independence from the Republican government (the Sovereign Council had its own ministers, symbols, etc.) and increased its vulnerability to the approaching rebel front in the east.[50] On October 18, Villaviciosa fell, and on October 21, Gijón followed suit, with the entire Asturias and the northern region falling into Nationalist hands.

Demoralization in the days before the fall of Gijón was total, with many prominent leaders fleeing from El Musel, leading to numerous desertions and a sense of "every man for himself." Naval vessels, merchant ships, and even fishing boats were used to evacuate soldiers and civilians (some managed to escape the Nationalist blockade, while others were captured, and one, the destroyer Ciscar, was sunk in the harbor).[51] Other Republicans fled to Catalonia, and some took to the mountains, forming guerrilla groups or "maquis", which persisted for a few years.[52]

Post-war period

Consequences of the war in Asturias:

- Countless material losses, including destroyed industries and devastated fields (production decreased in the subsequent years to levels 20 to 29% lower than those reached before the Republic).

- Hunger and diseases (tuberculosis).

- Destruction of buildings (in Oviedo, three-fifths of the city's buildings were destroyed, including severe damage to the cathedral and numerous churches and convents).

- The number of dead is estimated to be over 16,000, with 11,500 killed in combat (only exceeded by Madrid), and over 5,000 victims of repression.

- More than 2,000 individuals were imprisoned during the early 1940s in prisons or labor camps.

- Several thousand people went into exile.

After the war, many of the working class population remained imprisoned or fled to the mountains, which forced the presence of a military force in the region. However, with the outbreak of the Second World War in 1939, coal and the metallurgical industry became of extraordinary importance, leading to the resurgence of the region.

Asturias between 1939-1981

During the Franco regime, Asturias experienced significant economic and demographic growth, supported by its industry and mining. In 1957, Francisco Franco inaugurated the first blast furnace of ENSIDESA, a steel company owned by the INI (Instituto Nacional de Industria). ENSIDESA had been planned since 1945 and construction began in 1954 to the east of Avilés.[54]

Meanwhile, the three privately owned steel companies, Mieres Factory, Felguera, and Moreda-Gijón, merged in May 1961 under the name UNINSA (Unión de Siderúrgicas Asturianas Sociedad Anónima) and decided to build a new plant to the west of Gijón, which started operating in 1971, leading to the closure of the old three historical factories.[55] However, just two years after its establishment, UNINSA joined ENSIDESA in 1973, forming a state mega-factory between the two.[56] The disappearance of the steel industry in the mining areas caused migratory changes between Cuencas, Avilés, and Gijón. These mining regions continued to maintain their dominance during this time, although a successful but repressed mining strike occurred in 1962.[57]

The construction of the Labor University in Gijón began in 1948, which has been a professional training center for thousands of Asturians since its opening in 1955.[58]

On July 11, 1968, the Asturias Airport was inaugurated, replacing the La Morgal airport.[59] In 1976, opened the "Y Griega", the first Asturian carriageway, connecting Avilés, Oviedo, and Gijón through a system of three branches joined in a road junction in Serín. It currently forms part of the A-66 and A-8 highways.[60] All these advancements and more in the region were showcased at the FIDMA exhibition starting from 1963, serving as a technical, commercial, industrial, and touristic showcase of Asturias.[61]

Asturias since the Transition (1981-Present)

Industrial restructuring

This period in Asturias is marked by a strong industrial reconversion.[62] Virtually all sectors are affected by job cuts and shutdowns. The industrial reconversion, which took place approximately between 1986 and 1995 as part of the government's plans to align with the European Union, resulted in staggering unemployment figures in Asturian cities, reaching 24% in Avilés in 1988[63] and 26% in Gijón in 1987.[64] In 1996, Asturias reached 123,000 unemployed individuals.[65] For example, ENSIDESA went from employing 21,012 workers in 1984 to 14,885 workers in 1990.[66] Nevertheless, it remained the largest company in Asturias, accounting for 23% of industrial employment in 1993.[64] In 1997, ENSIDESA was privatized and renamed Aceralia, under Luxembourg ownership.[65]

Furthermore, there was a demographic stagnation and a significant release of urban land, particularly in Gijón[67] and to a lesser extent in Avilés[68] and Cuencas.

Political evolution

With the arrival of democracy in Spain, the Regional Council of Asturias was created as a provisional pre-autonomous body, presided over by Rafael Fernández Álvarez. On December 30, 1981, the Statute of Autonomy of Asturias was approved, establishing the creation of the autonomous community of the Principality of Asturias.

In May 1983, the first regional elections were held. Pedro de Silva Cienfuegos-Jovellanos, from the PSOE, was elected President of the Principality of Asturias.[69] Pedro de Silva was succeeded by Juan Luis Rodríguez-Vigil (PSOE) in 1991, who resigned in 1993 due to the Petromocho case.[70] Antonio Trevín assumed the position of President of the Principality.

In the 1995 elections, the People's Party achieved a simple majority in the Principality of Asturias' Assembly, and Sergio Marqués was elected president. In 1998, due to differences with his party, Sergio Marqués left the People's Party and founded the Asturian Renewal Union, governing in minority until the 1999 elections.[71]

In 1999, the PSOE obtained an absolute majority, and Vicente Álvarez Areces was appointed President of the Principality of Asturias. From July 22, 2003, he governed with the support of IU (United Left) and in 2007 he won the elections again and, although he failed to obtain an absolute majority, he once again took office, followed by Vicente Álvarez Areces "Tini" as president.[72]

In 2011, the newly founded party Foro Asturias, led by Francisco Álvarez Cascos, won the elections and became the first party in democracy to win in its first electoral contest. In 2012, Álvarez Cascos called for new elections and was defeated, leading to Javier Fernández Fernández, the Secretary General of the Socialist Federation of Asturias (PSOE), becoming president. In the 2015 elections, he revalidated his victory and governed in a minority with the support of IU. On July 15, 2019, Adrián Barbón, from the FSA-PSOE, was elected president.[73]

Events of the 21st century

.jpg.webp)

Thanks to industrial reconversion, Asturias witnessed a reconfiguration of its urban spaces with the construction of facilities such as the Oscar Niemeyer International Cultural Center (Avilés, 2011),[68] the ZALIA (Zona de Actividades Logísticas e Industriales de Asturias) industrial park (Gijón, 2006),[74] the Laboral, City of Culture (Gijón, 2007),[75] the Parque Prin shopping center (Siero, 2001),[76] the interurban highways Minera, Industrial, Oviedo-Villaciosa, and Oviedo-La Espina, the expansion of the Port of Gijón (2012),[77] the Variante de Pajares (2023),[78] the Road Plan in Gijón,[79] and the HUCA (Hospital Universitario Central de Asturias) in Oviedo (2014).[80]

The COVID-19 pandemic in Asturias resulted in the deaths of more than 3,120 people.[81] The Asturian economy was affected but managed to recover in the following years.[82] Additionally, the region was negatively impacted by the economic consequences of the Russian invasion of Ukraine in 2022.[83]

Asturias entered the 21st century with significant demographic challenges, with an aging population that threatens to fall below one million inhabitants in the Principality.[84]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "Toponimia asturiana - El porqué de los nombres de nuestros pueblos". mas.lne.es (in Spanish). Retrieved October 15, 2022.

- 1 2 3 Cuervo Álvarez, Benedicto. "Castro de Coaña, Asturias, en Waste Magazine". Waste Magazine (in Spanish). Retrieved September 30, 2022.

- ↑ "Castros de Asturias | Arqueología castreña, excavaciones, yacimientos visitables, catálogos y bibliografía arqueológica". www.castrosdeasturias.es (in Spanish). Retrieved September 30, 2022.

- ↑ "Artículo : Historia y cultura - Gobiernu del Principáu d'Asturies". asturias (in Spanish). Retrieved September 30, 2022.

- ↑ "Gijón, referente del mundo romano en el Cantábrico". nationalgeographic (in Spanish). April 10, 2019. Retrieved September 30, 2022.

- 1 2 González Echegaray, p. 154)

- ↑ González Echegaray, p. 156)

- ↑ González Echegaray, p. 158)

- ↑ González Echegaray, p. 163)

- ↑ González Echegaray, p. 162)

- ↑ González Echegaray, p. 166)

- ↑ González Echegaray, p. 147)

- ↑ Santos Yanguas (2017, p. 157)

- ↑ Santos Yanguas (2017, p. 159)

- ↑ Ordóñez, Luis (September 7, 2020). "Los tres momentos históricos en los que Asturias pudo ser independiente". La Voz de Asturias (in Spanish). Retrieved January 10, 2022.

- ↑ Ruano, Eloy Benito; Ruiz de la Peña, Juan Ignacio (1999). Los orígenes del Principado de Asturias y de la Junta Genera (in Spanish). Junta General del Principado de Asturias.

- ↑ "Historia de la institución - Junta General del Principado de Asturias" (in Spanish). Retrieved January 10, 2022.

- ↑ Peláez (2002, pp. 66–68)

- ↑ Peláez (2002, p. 74)

- ↑ Peláez (2002, p. 79)

- ↑ Peláez (2002, pp. 80–83)

- ↑ "Universidad de Oviedo - Fundación y siglo XVII". uniovi (in Spanish). Retrieved January 10, 2022.

- ↑ Iglesias, José Luis (May 25, 2016). "En recuerdo del 25 de mayo de 1808". La Voz de Asturias (in Spanish). Retrieved January 10, 2022.

- ↑ "25 de mayo: tal día como hoy en 1808 Asturias declara la guerra a Francia". Infodefensa (in Spanish). Retrieved January 10, 2022.

- 1 2 3 "Las guerras carlistas (1979)". La Carlistada (in Spanish). December 11, 2016. Retrieved January 10, 2022.

- ↑ "El Desarme de Oviedo: Tres teorías para una celebración". La Voz de Asturias (in Spanish). October 17, 2018. Retrieved January 1, 2022.

- ↑ Arrieta Berdasco, Valentín (April 2, 2016). "La desaparecida muralla carlista". El Comercio (in Spanish).

- 1 2 3 4 "La Ilustración asturiana | artehistoria.com". artehistoria (in Spanish). Retrieved October 1, 2022.

- ↑ "Biografía de Benito Jerónimo Feijoo - Benito Jerónimo Feijoo". Biblioteca Virtual Miguel de Cervantes (in Spanish). Retrieved October 1, 2022.

- ↑ "Biografia de Gaspar Melchor de Jovellanos". biografiasyvidas (in Spanish). Retrieved October 1, 2022.

- ↑ "El Ferrocarril de Langreo, 150 años moviendo a Asturias". vialibre-ffe (in Spanish). 2002. Retrieved October 1, 2022.

- ↑ García Quirós, p. 2)

- ↑ García Quirós, p. 3)

- ↑ García Quirós, p. 5)

- ↑ García Quirós, p. 11)

- ↑ Burgos, Ernesto (June 28, 2022). "El optimismo de la Asturian Mining Company" (in Spanish). Retrieved October 1, 2022.

- ↑ Montañés, D. (July 26, 2009). "Fábrica de Mieres, una huella de 130 años". La Nueva España (in Spanish). Retrieved October 1, 2022.

- ↑ "Factoría de Duro Felguera". Patrimonio Industrial Asturias (in Spanish). Retrieved October 1, 2022.

- ↑ Granda, Javier (April 18, 2009). "Fábrica Siderúrgica de Moreda 1879-1954". La Nueva España (in Spanish). Retrieved October 1, 2022.

- ↑ "La primera época". Minas de Asturias (in Spanish). Retrieved October 1, 2022.

- ↑ Álvarez Buylla, Virginia (June 20, 2012). "La minería asturiana: crónica de una muerte anunciada". La Nueva España (in Spanish). Retrieved October 1, 2022.

- ↑ Montepio, Alberto (January 1, 2021). "La Asturias minera, reino de "castilletes" con mucha historia". Montepío y Mutualidad de la Minería Asturiana (in Spanish). Retrieved October 1, 2022.

- 1 2 Laso Prieto, José María. "Historia del movimiento obrero en Asturias". nodulo (in Spanish). Retrieved October 1, 2022.

- 1 2 3 4 "El movimiento obrero en Asturias". union-communiste (in Spanish). 2014.

- ↑ Claudín, Fernando (1985). "Algunas reflexiones sobre Octubre 1934". Octubre 1934. Cincuenta años para la reflexión (in Spanish). pp. 43–44.

- ↑ Bayerlein, Bernhard (1985). "El significado internacional de Octubre de 1934 en Asturias. La Comuna Asturiana y el Komintern". Octubre 1934. Cincuenta años para la reflexión (in Spanish). pp. 19–40.

- ↑ Payne, Stanley G. (1973). "A History of Spain and Portugal (Print Edition)". University of Wisconsin Press (in Spanish). 2: 637. Retrieved April 10, 2012.

- ↑ Ruiz, David (1988). Historia de Comisiones Obreras (1958-1988) (in Spanish).

- ↑ Richards, Michael (2005). The Splintering of Spain. p. 54.

- 1 2 3 Viana, Israel (March 26, 2020). "Así se gestó la independencia de Asturias en la Guerra Civil con su propia moneda, presidente y ministros". abc (in Spanish). Retrieved October 1, 2022.

- 1 2 3 "Guerral Civil en Gijón". Vink (in Spanish).

- ↑ García Piñeiro, Ramón (2015). "Días de Diario". Luchadores del ocaso: Represión, guerrilla y violencia política en la Asturias de posguerra (1937-1952) (in Spanish). KRK Ediciones. ISBN 978-84-8367-493-2.

- ↑ Piñera, Luis Miguel (July 18, 2010). "Un ejemplo de modernidad". La Nueva España (in Spanish). Retrieved September 18, 2022.

- ↑ Benito del Pozo & Carrera (2012, p. 4)

- ↑ Benito del Pozo & Carrera (2012, p. 5)

- ↑ Benito del Pozo & Carrera (2012, p. 6)

- ↑ "La 'huelgona' que hizo historia". El Comercio (in Spanish). April 8, 2012. Retrieved October 2, 2022.

- ↑ Ramos, Javier (March 27, 2014). "Universidad Laboral de Gijón". Lugares Con Historia (in Spanish). Retrieved October 2, 2022.

- ↑ "Historia del aeropuerto de Asturias | Aena". aena (in Spanish). Retrieved October 2, 2022.

- ↑ Muñiz, Ramón (February 7, 2016). "La 'Y' cumple 40 años uniendo Gijón, Oviedo y Avilés". El Comercio (in Spanish). Retrieved October 2, 2022.

- ↑ "Feria de Muestras de Asturias - HISTORIA GRÁFICA (1924-2016)". Camara Gijon (in Spanish).

- ↑ Granda Cañedo (2014, p. 12)

- ↑ Benito del Pozo & Carrera (2012, p. 7)

- 1 2 Granda Cañedo (2014, p. 16)

- 1 2 Granda Cañedo (2014, p. 21)

- ↑ Granda Cañedo (2014, p. 15)

- ↑ Granda Cañedo (2014, p. 27)

- 1 2 Benito del Pozo & Carrera (2012, p. 8)

- ↑ "Silva Cienfuegos-Jovellanos, Pedro de". Biografias Asturias (in Spanish). Retrieved September 30, 2022.

- ↑ Granda Cañedo (2014, p. 19)

- ↑ Cuartas, Javier (May 8, 2012). "Sergio Marqués, el presidente de Asturias al que defenestró Cascos". El País (in Spanish). ISSN 1134-6582. Retrieved September 30, 2022.

- ↑ "Muere el expresidente de Asturias Vicente Álvarez Areces". La Vanguardia (in Spanish). January 17, 2022. Retrieved September 30, 2022.

- ↑ "Adrián Barbón, elegido presidente de Asturias| RTVE". RTVE (in Spanish). July 15, 2019. Retrieved September 30, 2022.

- ↑ Granda Cañedo (2014, p. 26)

- ↑ "Laboral Ciudad de la Cultura: Transformación". Laboral ciudad de la cultura (in Spanish). Retrieved October 2, 2022.

- ↑ "Parque Principado cumple 20 primaveras". La Voz de Asturias (in Spanish). March 23, 2021. Retrieved October 7, 2022.

- ↑ "Ampliación Puerto Musel Gijón (Dique Torres)". AVG Alvargonzález Contratas (in Spanish). Retrieved October 2, 2022.

- ↑ "La variante ferroviaria de Pajares entrará en funcionamiento en mayo de 2023". La Vanguardia (in Spanish). June 21, 2022. Retrieved October 2, 2022.

- ↑ Muñiz, R. (September 1, 2022). "El plan de vías cumple 20 años con doce millones usados en estudios y maquetas". El Comercio (in Spanish). Retrieved October 2, 2022.

- ↑ "El nuevo HUCA se estrena mañana con 18 pacientes de oncología". La Nueva España (in Spanish). January 20, 2014.

- ↑ "Covid 19 en Asturias". app.powerbi (in Spanish). Retrieved October 2, 2022.

- ↑ "La economía asturiana, a punto de cerrar la brecha con el PIB prepandemia". La Voz de Asturias (in Spanish). May 23, 2022. Retrieved October 2, 2022.

- ↑ Castaño, Pablo (April 3, 2022). "La tormenta perfecta: los economistas resaltan la peligrosa confluencia de crisis en Asturias por la inflación". La Nueva España (in Spanish). Retrieved October 2, 2022.

- ↑ Menéndez, X. (April 25, 2022). "¿Hay solución a la crisis demográfica asturiana?". La Voz de Asturias (in Spanish). Retrieved October 2, 2022.

Bibliography

- Cañada, Silverio (1970). Gran Enciclopedia Asturiana (in Spanish). Gijón. ISBN 84-7286-022-1.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Álvarez, Manuel Fernández (2003). Isabel la Católica (in Spanish). Madrid: Espasa Calpé. ISBN 84-670-1260-9.

- Erice, Francisco; Uría, Jorge (1990). Historia básica de Asturias (in Spanish). Gijón.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - Fernández Pérez, A.; Friera Suárez, F.; Camino Mayor, Jorge; Miguel, Calleja Puerta; Fernández Álvarez, José Manuel; Friera Álvarez, Marta; Rodríguez Infiesta, Víctor (2005). Historia de Asturias (in Spanish). Oviedo: KRK Ediciones. ISBN 84-96476-60-X.

- Santos Yanguas, Narciso (2017). "La conquista de Asturias por Roma: una nueva perspectiva". Gerión. Revista de Historia Antigua (in Spanish). 35. doi:10.5209/GERI.56142.

- González Echegaray, Joaquín. "Las Guerras Cántabras en las fuentes" (PDF) (in Spanish).

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - Peláez, Roberto J. (2002). "Población y economía en la Asturias del siglo XVII". J. Menéndez Peláez y Otros, la Lliteratura Asturiana Nel Cuartu Centenariu de Antón de Marirreguera, ed. Trabe, Oviedo (España) (in Spanish). Oviedo: Trabe.

- García Quirós, Paz. Minería y ferrocarril minero en Asturias a finales del siglo XIX (PDF) (in Spanish). Museo del Ferrocarril de Asturias.

- Benito del Pozo, Paz; Carrera, José Luis (2012). El impulso del franquismo a la siderurgia en Asturias y su eco patrimonial (PDF) (in Spanish). Universidad de León.

- Granda Cañedo, Álvaro (2014). Efectos socioculturales de los procesos de deslocalización y desindustrialización en el concejo de Gijón (2000-2013) (in Spanish). Universidad de Oviedo.

External links

- History of Asturias.(in Spanish)