The history of human habitation in the Andean region of South America stretches from circa 15,000 BCE to the present day. Stretching for 7,000 km (4,300 mi) long, the region encompasses mountainous, tropical and desert environments. This colonisation and habitation of the region has been affected by its unique geography and climate, leading to the development of unique cultural and socn.

After the first humans — who were then arranged into hunter-gatherer tribal groups — arrived in South America via the Isthmus of Panama, they spread out across the continent, with the earliest evidence for settlement in the Andean region dating to circa 15,000 BCE, in what archaeologists call the Lithic Period. In the ensuing Andean preceramic period, plants began to be widely cultivated, and first complex society, Caral-Supe civilization, emerged at 3500 BC, and lasted until 1800 BC. Also, distinct religious centres emerged, such as the Kotosh Religious Tradition in the highlands.

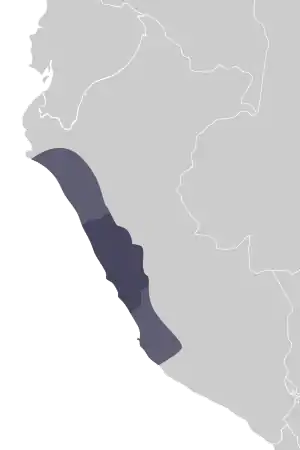

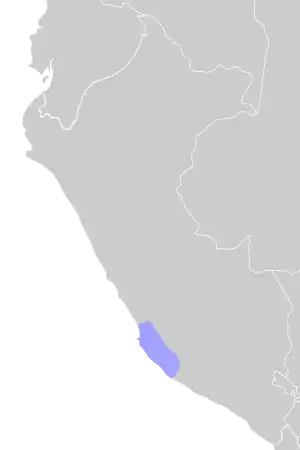

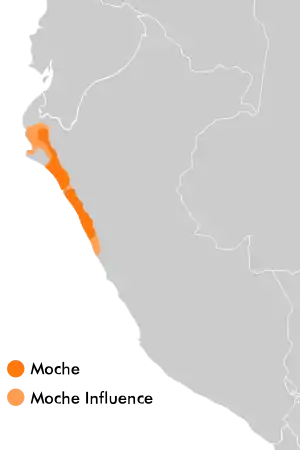

This was followed by the Ceramic Period. Various complex societies developed at this time, such as Chavín culture, lasting from 900 BC to 200 BC, Paracas culture, lasting from 800 BC to 200 BC, its successor Nazca culture, lasting from 200 BC to 800, the Moche civilisation, lasting from 100 to 700, Wari and Tiwanaku Empires, with both lasting from 600 to 1000, and Chimor, lasting from 900 to 1470. In later periods, much of the Andean region was conquered by the indigenous Incas, who in 1438 founded the largest empire that the Americas had ever seen, named Tahuantinsuyu, but usually called Inca Empire. The Inca governed their empire from the capital city of Cuzco, administering it along traditional Andean lines. Inca Empire rose from Kingdom of Cuzco, founded around 1230.

In the 16th century, Spanish colonisers from Europe arrived in the Andes, eventually subjugating the indigenous kingdoms and incorporating the Andean region into the Spanish Empire. In the 19th century, a rising tide of anti-imperialist nationalism that was sweeping all of South America led rebel armies to overthrow Spanish rule. The Andean region was subsequently divided into a number of new states, Peru, Chile, Bolivia and Ecuador. The 20th century saw the growing influence of the United States in the region, which was increasingly exploited for its natural gas supplies. This in turn led to the rise of a number of anti-imperialist and socialist movements to oppose U.S. and multinational involvement in Andean South America.

Lithic Period: c.15,000 BCE—3500 BCE

The earliest period in which humans inhabited the Andean region was the Lithic period, sometimes alternately called the Early Archaic period. It was a period characterised by the use of stone tools, or lithics, as the main form of technology, and a hunter-gatherer mode of existence.

First colonisation

After the evolution of anatomically modern humans in East Africa circa 200,000 years ago, the species spread across the African continent and into Europe and Asia. It was from the Bering land bridge between Siberia in Northeast Asia and Alaska in north-western North America that humans first crossed into the Americas. From there, vanguards of human groups headed south, colonising the rest of the continent before reaching the Isthmus of Panama and crossing into the continent of South America.[1][2] Although there had been four biologically distinct genetic human populations in North America, as has been identified by DNA analysis, only one of these populations, that known as the Paleo-Indians, pushed as far south as Mesoamerica and South America, meaning that the indigenous inhabitants of that latter continent were genetically homogenous.[3]

Comparative analysis of indigenous religious beliefs across South America have led academics to suspect that the first Paleo-Indian colonists of the continent would have believed in a multi-layered universe in which the Earth was suspended between a celestial outer sphere and a cavernous inner sphere. There would have been strong taboos against incest, something that would have prevented inbreeding (a particular problem amongst the genetic homogeneity of the Indigenous South Americans), and instead marriage was controlled by social conventions, such as the development of moiety systems of societal duality.[4]

The first pioneers in South America, migrating down south from the Isthmus of Panama, would likely have avoided the largely mountainous Andean region, because the upper Cordillera was glaciated, cold and sparsely vegetated, making life there difficult, whilst these early populations would have suffered from hypoxia. Instead, the early hunter-gatherer pioneers would have most likely stuck to the margins of the continent, where they could exploit the resources in the rivers, deltas and salt-water lagoons. Gradually, generation by generation, as the population grew, these Indigenous Americans spread out throughout the continent, with some groups eventually reaching the Andean region. They would have most likely initially inhabited the coastal lowland areas, only travelling up into the mountains to obtain resources like obsidian. Gradually, as their descendants became acclimatised to the altitude, groups of humans began to move up and inhabit higher points of the Andes.[5]

One of the earliest known Andean sites that have been properly investigated by archaeologists is that at Monte Verde in Southern Chile, which has been radiocarbon dated to 14,800 years ago. At this site, there was evidence for seasonal settlement along the sandy banks of a creek in the subarctic pine forests of the low southern Cordillera, at which were found preserved wooden and stone tools, remnants of wild vegetables such as potatoes, and the skeletal remains of five or six mastodons which had been scavenged or hunted by the human occupants.[6] Other Lithic period sites that have been discovered in the Andean region include Los Toldos (Santa Cruz) in Argentina, and San Vicente de Tagua Tagua, Cueva Fell (Fell's Cave), and Quero in contemporary Chile. Pikimachay, the cave of Jaywamachay (40 km southwest of Ayacucho), Huarago and Uschumachay in contemporary Peru are also important. From the evidence unearthed at all these sites it is apparent that at this time, the horse was the most commonly hunted species, although the sloth and guanaco were also apparent.[7]

Lithic adaptation

Due to the varied geographical areas in the Andean region, unique communities evolved to suit their own particular locations across the region in the latter part of the Lithic period. Archaeologists have defined these different communities by their unique types of stone tool designs, describing them as the Northwestern tradition, the coastal Paijan tradition, the Central Andean Lithic Tradition, and the Atacama Maritime Tradition.[8]

It was also in this period that Andean communities first began to domesticate crops, genetically transforming various plant species from their wild counterparts.[9]

Pre-Ceramic Period: c.3500 BCE—c.2000 BCE

Overview

The Lithic Period was followed by what archaeologists have called the Pre-Ceramic Period, or alternatively the Late Archaic Period, and is characterised by increasing societal complexity, rising population levels and the construction of monumental ceremonial centres across the Andean region.[10] It is the latter of these features that remains the most visually obvious characteristic of the Pre-Ceramic amongst archaeologists, and indicates that by this time, Andean society was sufficiently developed that it could organise large building projects involving the management of labor.[11] The Pre-Ceramic Period also saw a rise in the population of the Andean region, with the possibility that many people were partially migratory, spending much of their year in rural areas but moving to the monumental ceremonial centers for certain times which were seen as having special significance.[12] The Pre-Ceramic also saw changes in the climate of the Andean region, for the culmination of the Ice Age had led to an end of the glacial meltback which had been occurring throughout the Lithic Period, and as a result the sea levels on the west coast of South America stabilized.[13]

Despite these changes, many elements of Andean society remained the same as it had been in earlier millennia; for instance, as its name suggests, the Pre-Ceramic was also a period when Andean society had yet to develop ceramic technology, and therefore had no pottery to use for cooking or storage.[14] Similarly, Andean communities in the Pre-Ceramic had not developed agriculture or domesticated flora or fauna, instead gaining most of their food from what they could hunt or gather from the wild, just as their Lithic Period predecessors had done, although there is evidence that some wild plants had begun to be intentionally cultivated.[15]

Caral-Supe civilization

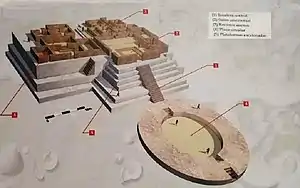

Caral-Supe civilization was the first civilization in pre-Columbian America, located in modern-day Peru, as well as one of world's oldest civilizations. It coalesced in 3500 BC, and large construction became apparent from 3100 BC. It lasted until 1800 BC. Among the largest cities were Caral and Aspero, the type site of civilization.

Ceramic Period: c.2000 BCE—1533

Overview

The development of ceramic technology in the Andean region, and the subsequent production of pottery for both cooking and storage, marks the beginning of Ceramic Period.[16] The introduction of pottery was however "simply one part of a much larger socioeconomic transformation" along the Andean coast, as communities ceased seeing their coastal settlements as the major centers of activity in favour of more inland locations, and as such the former maritime-based economy was replaced by one that was dominated by irrigation farming.[17]

Initial Period

Kotosh Religious Tradition

In the mountain drainage areas of the Andes, a series of ceremonial buildings were constructed that archaeologists have identified as being a part of what they called the Kotosh Religious Tradition.[18] One of the most prominent of these sites was that at Kotosh, after which the religious tradition was named. Located on the bank of the Río Higueras, Kotosh was at an elevation of c. 2000 metres above sea level, and consisted of "two large platform mounds flanked by lesser constructions and a number of small structures on a nearby river terrace."[19] Another notable example of the Kotosh Religious Tradition can be seen at La Galgada in the Callejón de Huaylas, modern Peru, which again consists of two platform mounds and several surrounding structures.[20]

In other parts of the Andean region, other traditions of ceremonial monument building also developed during the Pre-Ceramic period.

Powerful earthquake in Chile

In approximately 1800 BC, a very powerful earthquake struck in Chile, at the area of Atacama desert. It was one of the largest known earthquakes, with magnitude of approximately 9.5, same magnitude as Valdivia earthquake, the strongest earthquake in recorded history. It triggered tsunami that had height of around 20 meters and travelled through entire Pacific Ocean. It also created a new inland sea inside Atacama desert, which later dried out. The people in area where earthquake and tsunami struck were at that time hunter-gatherers, and they probably suffered considerable losses. After the earthquake and tsunami, the area was abandoned for about 1000 years, probably because of imprinted memory of people who lived there before.[21]

Early Horizon

Chavin culture

Chavin culture was an Early Horizon civilization, which arose in 900 BC, and persisted until 200 BC. Its characteristics were intensification of religious cult and appearance of metallurgy and textiles, as well as improvements in agriculture.

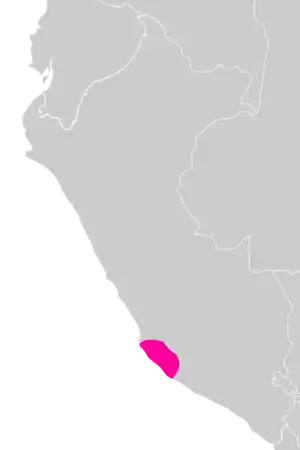

Paracas culture

Paracas culture was an archaeological culture which arose in Peru, lasting from 800 BC to 100 BC. It is characterised by very fine textiles. It was the precursor of Nazca culture, which arose on its foundations in 100 BC.

Early Intermediate

Lima culture

Lima culture was a civilization that existed on the territory of modern-day city of Lima, from the 100 to 650.

Moche culture

Moche culture was a culture in northwestern Peru, flourishing between 100 and 700. It was a collection of culturally united, but politically autonomous polities. Supposed language of this culture is Mochica.

Nazca culture

Nazca culture was the culture in southwestern Peru, that arose in 100 BC on the foundations of earlier Paracas culture. It is famous for Nazca Lines, extensive network of geoglyphs whose purpose is still unknown. They also produced textiles, and build puquios, a network of aqueducts, of whom some are still in function today.

Middle Horizon

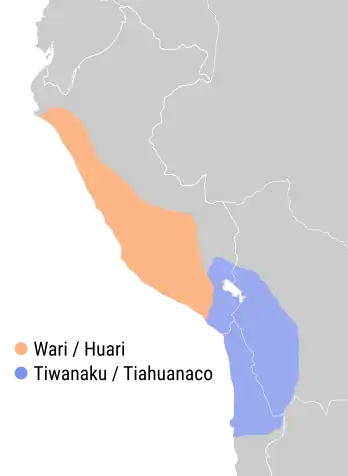

Wari Empire

Wari Empire was a political entity in modern-day Peru that arose in 600, and collapsed around 1000, concurrent with Tiwanaku Empire. Its capital was city of Huari.

Tiwanaku Empire

Tiwanaku Empire was a polity that existed in modern-day Bolivia from 600 to 1000. Its capital, Tiwanaku, was in year 800 one of the largest cities in pre-Columbian America, with population estimates ranging from 10 000 to 20 000. It is also notable for its advanced stonework, especially at the site of Pumapunku, which is ruin of the complex. It is not considered to be a real empire, but rather a collection of loosely connected cities, since there is no evidence of any dynasties, state-maintained roads and markets.

Late Intermediate

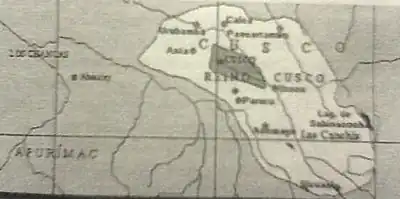

Kingdom of Cusco

Kingdom of Cusco was a small kingdom based at the city of Cusco. It was founded around 1230 by Manco Capac, who was also the first Sapa Inca. It was the predecessor of Inca Empire, founded in 1438 by Sapa Inca Pachacuti.

Chimor

Chimor was a political entity of Chimor culture that lasted from 900 up until Incan conquest in 1470. This culture was founded at the site of earlier Moche culture. It was a monarchy and unified state. Supposed languages in this states were Mochica, language of earlier Moche culture, and Quignam, language of Chimor people.

It is the culture which performed the largest mass sacrifice of children known, which was discovered in 2011, and was performed between 1400 and 1450, with 227 victims. They are also known for Punta Lobos massacre, which was discovered in 1997. It was carried out around 1350 and approximately 200 people were killed, and they were blindfolded and handcuffed. It is also postulated to be an example of mass sacrifice.

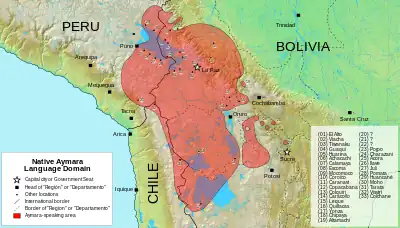

Aymaran kingdoms

Aymara kingdoms were a group of Aymaran polities flourishing between 1150 and 1477. They appeared after the collapse of Tiwanaku Empire. There were 12 major Aymara kingdoms.

Late Horizon

Inca Empire

.svg.png.webp)

It was in the Late Horizon that an Inca Empire rose up across the entire stretch of the Andes. It was called Tahuantinsuyu, meaning "The Four Regions" in the Quechua language.

It rose up in 1438, from the Kingdom of Cuzco, with its first emperor being Pachacuti. In the following decades, under the leadership of Pachacuti's son Tupac Inca Yupanqui, reigning from 1471 to 1493, it expanded rapidly, and by the arrival of Columbus, it was the largest empire of Pre-Columbian Americas. The next emperor, Huayna Capac, ruled until c. 1527, when he suddenlu died from smallpox, introduced by Europeans. His death set a civil war between his sons that, in combination with smallpox, weakened the empire, and it was eventually conquered by Francisco Pizzaro in 1533, beginning the period of European colonisation, and becoming the part of the Spanish Empire.

Although Inca Empire was drawing "heavily upon the technological and organizational accomplishments of earlier Andean cultures", the Incan rulers refused to accept these antecedents, instead claiming that prior to the rise of Tahuantinsuyu, the Andes had merely been inhabited by primitive warlike tribes that the Incan tribe unified under their own civilising influence.[22]

European colonisation: 1533 to 19th century

The Andean region became a part of the Spanish Empire.

Wars of Independence

A key figure in the Latin American wars of independence was Simón Bolívar; in gratitude the nation of Bolivia adopted its name after him.

Post-colonial period: 19th century to present

Post-war development

In 1969, five Andean states — Bolivia, Chile, Colombia, Ecuador and Peru — founded their own trade bloc, the Andean Pact, and in 1973 were joined by Venezuela. In 1976, Chile withdrew from the Pact after President of Chile Augusto Pinochet declared the Pact incompatible with his right-wing views. The Pact was renamed the Andean Community of Nations in 1996.

The Pink Tide

In the 21st century, leftist presidents were elected to power in several Andean states, as a part of the wider "pink tide" then sweeping Latin America, in which the political left gained increasing power as a reaction against the Washington Consensus. In 2006, Evo Morales of the Movement for Socialism party was elected President of Bolivia, whilst later that year Rafael Correa of the PAIS Alliance was elected President of Ecuador; both Morales and Correa were socialists, nationalising industry and opposing United States influence in their respective nations. Instead, both allied themselves with the government of Venezuela, then led by Hugo Chávez and his United Socialist Party of Venezuela, and joined the Bolivarian Alliance for the Americas, a trade bloc between Latin America's socialist nations.

References

Footnotes

- ↑ Moseley 2001. p. 87.

- ↑ Burger 1992. pp. 08-11.

- ↑ Moseley 2001. pp. 87-88.

- ↑ Moseley 2001. p. 88.

- ↑ Moseley 2001. pp. 88-89.

- ↑ Moseley 2001. pp. 89-90.

- ↑ Moseley 2001. p. 91.

- ↑ Moseley 2001. p. 92.

- ↑ Moseley 2001. pp. 102-103.

- ↑ Moseley 2001. p. 107.

- ↑ Burger 1992. p. 27.

- ↑ Moseley 2001. p. 114.

- ↑ Moseley 2001. p. 107.

- ↑ Burger 1992. p. 27.

- ↑ Moseley 2001. p. 107.

- ↑ Burger 1992. p. 57.

- ↑ Burger 1992. p. 57.

- ↑ Moseley 2001. p. 109.

- ↑ Moseley 2001. p. 109.

- ↑ Moseley 2001. p. 109.

- ↑ "The largest super earthquake in ancient history, pushed the tsunami halfway around the world - Blogtuan.info". 2022-04-17. Retrieved 2022-06-24.

- ↑ Burger 1992. p. 7.

Bibliography

- Burger, Richard L. (1992). Chavin and the Origins of Andean Civilisation. London: Thames and Hudson. ISBN 978-0-500-27816-1.

- Mann, Charles C. (2005). Ancient Americans: Rewriting the History of the New World. Granta. ISBN 978-1-86207-617-4.

- Moseley, Michael E. (2001). The Incas and their Ancestors (second edition). London: Thames and Hudson. ISBN 978-0-500-28277-9.