Henry Stacy Marks | |

|---|---|

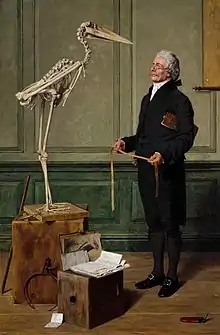

Self-portrait (1882; Aberdeen Art Gallery) | |

| Born | 13 September 1829 London, England |

| Died | 9 January 1898 (aged 68) London, England |

| Known for | Painter, illustrator |

| Movement | Pre-Raphaelites |

| Spouse(s) | Helen Drysdale (1856–1892) Mary Harriet Kempe (1893) |

| Patron(s) | Hugh Grosvenor, 1st Duke of Westminster |

Henry Stacy Marks RA (13 September 1829 – 9 January 1898) was a British artist who took a particular interest in Shakespearean and medieval themes in his early career and later in decorative art depicting birds and ornithologists as well as landscapes. Most of his early works were oils but he also worked on murals and with watercolours. He was a founding member of the St John's Wood Clique and was well known for his humorous performances.

Life and work

Marks was the fourth child of John Isaac Marks and Elizabeth (née Pally). His father was a solicitor who later became a coach builder. One of his brothers was the writer John George Marks. Henry studied in small schools near Regent's Park and at Eythorne, Kent where he learned to paint heraldry symbols so as to assist his father in his carriage making business. In 1845 he worked for a friend of his father as a clerk in a warehouse. He later went to work with his father and around 1846 he attended evening classes at James Mathews Leigh's art school where he would become a friend of Frederick Walker (Marks' younger brother later married Walker's twin sister).[1] For some time he worked for magazines like Home Circle producing wood-cut illustrations. After being rejected once, Henry enrolled successfully at the Royal Academy Schools in December 1851. In 1852 his father sold off the carriage-making business leaving Henry free to attend classes. He however decided to move to Paris with his friend Philip Hermogenes Calderon to study at the atelier of François Edouard Picot and the École des Beaux-Arts. He returned in June 1852, leaving Calderon in Paris and first exhibited at the Royal Academy in 1853, painting a scene from Shakespeare's Much Ado about Nothing: Dogberry Examining Conrad and Borachio. His works during the 1850s and 1860s were predominantly based on Shakespeare's plays and depicted medieval scenes.[2]

Marks' father emigrated to Australia leaving Henry to support his mother, three brothers and from October 1856, his wife, Helen Drysdale (1829-1892). He supplemented his income from painting by carrying out decorative work for various patrons. These included the Minton works, for the stained-glass manufacturers Clayton and Bell, by designing a frieze for the outside wall of the Royal Albert Hall, and for the house of the artist Lawrence Alma-Tadema. His early works on medieval themes included Toothache in the Middle Ages (1856) which was bought by the publisher Charles Edward Mudie with whom he became a friend. Marks' most important patron was Hugh Grosvenor, 1st Duke of Westminster. He was briefly an art critic for The Spectator, writing under the pen-name of "dry-point".[3] Marks worked on decorations for the house of the Duke of Westminster at Eaton Hall, Cheshire, between 1874 and 1880. For this purpose he painted two canvasses 35 feet (11 m) long of Chaucer's pilgrims in the saloon, and twelve panels of birds in the drawing room.[2]

Marks was a founding member of the St John's Wood Clique in 1862 along with Calderon. The aim of the clique was to improve each other by critique and the motto framed by Calderon was "the better each man's picture, the better for all." Marks was also an entertainer in the group with his fake sermons and songs. He was much loved in the club and was known as "Marco". He is shown in a cartoon A vision of the clique by Frederick Walker. Marks was a good friend of several of the cartoonists of Punch including John Tenniel and Charles Keene.

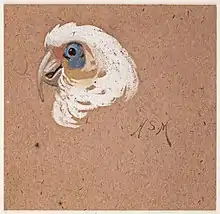

In 1888 the Fine Art Society planned an exhibition on birds and Marks decided to use this opportunity to take up an intensive study of birds and he became a regular visitor at the zoo. In 1890 he had a private exhibition on his bird works.[4] As his career progressed, he became increasingly interested in painting birds. Possibly his most famous painting is A Select Committee (1891) which is now in the Walker Art Gallery. He was elected as a member of the Royal Academy following his painting Convocation, which was exhibited in 1878. Both of these demonstrated his interest in birds, in the former parrots and in the latter adjutant storks and in general his paintings depicted large birds and the colourful parrots and he visited the London Zoo regularly to observe them. His early works were in oil (The Convent Raven, 1870) but many of his paintings of birds were watercolours, which he exhibited at the Old Watercolour Society or at the Fine Art Society. St Francis Preaching to the Birds (1870), was first sold for sold for £450 and seven years later for £1155. His diploma work Science is measurement depicting a scientist with measuring instruments before the skeleton of an adjutant stork is considered a classic. He got the idea of painting this scene while taking measurements for his earlier paintings. "In making studies of the birds, I went to the Museum of the Royal College of Surgeons to take measurements of the bones, their proportionate length, &c. When I had obtained what information I needed, I came away, and crossing Lincoln's Inn Fields, it struck me that the occupation in which I had been engaged would furnish a good subject for the picture." To paint this picture he asked for advice on obtaining a skeleton of the adjutant stork from Sir William Flower that could be kept at home so that he could study it at leisure. Flower suggested a taxidermy artist and skeleton preparer in Camden Town who supplied him with a suitable specimen. Marks ensured that he counted the vertebrae and measured them carefully to make sure it was accurate. The title was decided after much discussion with artists and scientists and he submitted it as his diploma picture for the Royal Academy of Arts.[5] Abraham Dee Bartlett, superintendent at the London zoo, encouraged him to draw birds with accuracy rather than colour them with anthropomorphism. In later years he painted landscapes and seascapes based on studies in Southwold and Walberswick.[2][6]

Personal life

Marks was married in 1856, to Helen Drysdale. Helen died in 1892, and the following year Marks married Mary Harriet Kempe, who was also a painter. Although baptised in an Anglican church, Marks was brought up as a dissenter. A childhood of listening to sermons led him to rebel in later age to religious and other forms of authority by lampooning clerics and preaching bogus sermons.[2] In an interview to Strand Magazine in 1891 he recalled with his typical wit an anecdote:[7]

"I took home a picture to the Dook of Wellington one day, and, as I was taking it up in the hall, he comes by, and says, "Oh, you comes from Messrs. Bennett." "Yes, sir," I says. With that he passes on, and out comes at the front door a man dressed all in black, and comes up to me—his butler, I suppose. He says, "Do you know who you were a talking to just now?" "Yes, sir," I says, "Arthur Wellesley, better known as Dook of Wellington." Then, why don't you say "Your Grace to him ?" "Grace ?" says I, " why should I say grace for? there's no meat here. Where's the viands? Why, I said sir to him—a common title of respect between man and man." " Well," says he, " you are a rum sort of customer, you are. What do you call the Duke ?" "What do I call him ?" I says ; "a wholesale carcase butcher! Look at his career. He begins by going to France to learn the art of war, and then he goes to India and kills thousands of natives who were only defending their own country, and at last turns his arms against the country where he first learned the art of war, and murders thousands more. A wholesale carcase butcher: that's what I call him."

Marks considered the Royal Academy of Arts to be a clique and wrote on its politics as a parody ballad.[8]

He published a two-volume autobiography towards the end of his life titled Pen and Pencil Sketches (1894).

Death and legacy

Marks died on 9 January 1898 in his London home and was buried in Hampstead Cemetery. His estate amounted to a little over £9,600.[2]

The Victoria and Albert Museum holds three of Marks' finished watercolour studies of birds and eleven sketches for larger paintings.[2] Some of his works are exhibited in the Parrot House of Eaton Hall.[9]

References

- ↑ Marks (1894) v1:76.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Pennie, A. R. (2004). "Marks, Henry Stacy (1829–1898)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/18075. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ↑ Marks (1894) v2:1.

- ↑ Marks (1894) v2:147-148.

- ↑ Marks (1894). v2:52-54.

- ↑ Meynell, Wilfred (1887). The modern school of art. London: Cassell and Company. pp. 111–121.

- ↑ How, Harry (1891). "Illustrated Interviews. No. II. Henry Stacy Marks, R.A". The Strand Magazine. An Illustrated Monthly. 2: 111–120.

- ↑ Layard, George Somes (1892). The life and letters of Charles Samuel Keene. London: Sampson Low, Marston and Company. pp. 248–250.

- ↑ The Parrot House, Grosvenor Estate, archived from the original on 23 February 2009, retrieved 16 January 2009

External links

- 20 artworks by or after Henry Stacy Marks at the Art UK site

- Marks, Henry Stacy (1894). Pen and Pencil Sketches. volume 1 volume 2

- Bookplates by Henry Stacy Marks in the University of Delaware Library's William Augustus Brewer Bookplate Collection

- Archived profile on Royal Academy of Art