| Gulbadan Begum | |

|---|---|

| Shahzadi of the Mughal Empire | |

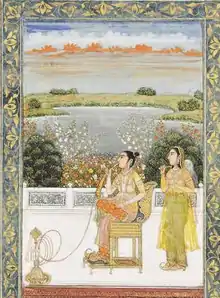

The imperial princess Gulbadan Begum | |

| Born | c. 1523 Kabul, Afghanistan |

| Died | 7 February 1603 (aged 79–80) Agra, India |

| Burial | Gardens of Babur, Kabul |

| Spouse |

Khizr Khan

(m. 1540) |

| Issue | Sa'adat Yar Khan |

| House | Timurid |

| Dynasty | Timurid |

| Father | Babur |

| Mother | Dildar |

| Religion | Sunni Islam |

Gulbadan Begum (c. 1523 – 7 February 1603) was a Mughal princess and the daughter of Emperor Babur, the founder of the Mughal Empire.[1]

She is best known as the author of Humayun-Nama, the account of the life of her half-brother, Emperor Humayun, which she wrote on the request of her nephew, Emperor Akbar.[2] Gulbadan's recollection of Babur is brief, but she gives a refreshing account of Humayun's household and provides a rare material regarding his confrontation with her half-brother, Kamran Mirza. She records the fratricidal conflict among her brothers with a sense of grief.

Gulbadan Begum[3] was about eight years old at the time of her father's death in 1530 and was brought up by her older half-brother, Humayun. She was married to a Chagatai noble, her cousin, Khizr Khwaja Khan, the son of Aiman Khwajah Sultan, son of Khan Ahmad Alaq of Eastern Moghulistan[4] at the age of seventeen.

She spent most of her life in Kabul. In 1557, she was invited by her nephew, Akbar, to join the imperial household at Agra. She wielded great influence and respect in the imperial household and was much loved both by Akbar and his mother, Hamida. Gulbadan Begum finds reference throughout the Akbarnama ("Book of Akbar"), written by Abu'l Fazl, and much of her biographical details are accessible through the work.

Along with several other royal women, Gulbadan Begum undertook a pilgrimage to Mecca, and returned to India seven years later in 1582. She died in 1603.

Name

Gulbadan Begum's name means "body like a rose flower" or "rose body" in the Persian language.[5]

Early life

When Princess Gulbadan was born in c. 1523 to Dildar Begum. Her father, Babur, had been lord in Kabul for 19 years; he was master also in Kunduz and Badakhshan, had held Bajaur and Swat since 1519, and Kandahar for a year. During 10 of those 19 years he had been styled Padshah, in token of headship of the House of Timur and of his independent sovereignty. Two years later Babur set out on his last expedition across the Indus to conquer an empire in India. Gulbadan's siblings included her older brother, Hindal Mirza, and two other sisters, Gulrang Begum and Gulchehra Begum, while her younger brother Alwar Mirza, died in his childhood. Among her siblings, Gulbadan was very close to her brother, Hindal Mirza.[6]

At the age of seventeen, Gulbadan was married to a Chagatai noble, her cousin, Khizr Khwaja Khan, the son of Aiman Khwajah Sultan, son of Khan Ahmad Alaq of Moghulistan.[7]

In 1540, Humayun lost the kingdom that his father Babur had established in India, to Sher Shah Suri, a Pashtun soldier from Bihar. With only his pregnant wife Hamida Banu Begum, one female attendant and a few loyal supporters, Humayun first fled to Lahore, and then later to Kabul. He was in exile for the next fifteen years in present-day Afghanistan and Persia. Gulbadan Begum went to live in Kabul again. Her life, like all the other Mughal women of the harem, was intricately intertwined with three Mughal kings – her father Babur, brother Humayun and nephew Akbar. Two years after Humayun re-established the Delhi Empire, she accompanied other Mughal women of the harem back to Agra at the behest of Akbar, who had begun his rule.

Writing of the Humayun Nama

Akbar commissioned Gulbadan Begum to chronicle the story of his father, Humayun. He was fond of his aunt and knew of her storytelling skills. It was fashionable for the Mughals to engage writers to document their own reigns (Akbar's own history, Akbarnama, was written by the well-known Persian scholar Abul Fazl). Akbar asked his aunt to write whatever she remembered about her brother's life. Gulbadan Begum took the challenge and produced a document titled Ahwal Humayun Padshah Jamah Kardom Gulbadan Begum bint Babur Padshah amma Akbar Padshah. It came to be known as Humayun-nama.[8]

Gulbadan wrote in simple Persian, without the erudite language used by better-known writers. Her father Babur had written Babur-nama in the same style, and she took his cue and wrote from her memories. Unlike some of her contemporary writers, Gulbadan wrote a factual account of what she remembered, without embellishment. What she produced not only chronicles the trials and tribulations of Humayun's rule, but also gives us a glimpse of life in the Mughal harem. It is the only surviving writing penned by a woman of Mughal royalty in the 16th century.

There has been suspicion that Gulbadan wrote the Humayun-Nama in her native language of Turkic rather than Persian, and that the book available today is a translation.[9]

Upon being entrusted with the directive by Akbar to write the manuscript, Gulbadan Begum begins thus:

There had been an order issued, ‘Write down whatever you know of the doings of Firdous-Makani (Babur) and Jannat-Ashyani (Humayun)’. At this time when his Majesty Firdaus-Makani passed from this perishable world to the everlasting home, I, this lowly one, was eight years old, so it may well be that I do not remember much. However in obedience to the royal command, I set down whatever there is that I have heard and remember.

From her account, we know that Gulbadan was married by the age of 17 to her cousin, Khizr Khwaja, a Chagatai prince who was the son of her father's cousin, Aiman Khwajah Sultan. She had at least one son. She had migrated to India in 1528 from Kabul with one of her stepmothers, who was allowed to adopt her as her own on the command of her father, the Emperor. After the defeat of Humayun in 1540, she moved back to Kabul to live with one of her half-brothers. She did not return to Agra immediately after Humayun won back his kingdom. Instead, she stayed behind in Kabul until she was brought back to Agra by Akbar, two years after Humayun died in a tragic accident in 1556. Gulbadan Begum lived in Agra and then in Sikri for a short while, but mostly in Lahore or with the Court for the rest of her life, except for a period of seven years when she undertook a pilgrimage to Mecca. The Mughal Court even up to the early years of Shah Jahan's reign was never a confined thing, but a travelling grand encampment and there is no doubt that Gulbadan Banu Begum, like most Mughal ladies, hated the confines living in buildings and no doubt, wholeheartedly agreed with the verses of Jahanara Begum, the daughter of Shah Jahan, that the rot of the empire would set in when the Mughals confined themselves to closed houses.

She appears to have been an educated, pious, and cultured woman of royalty. She was fond of reading and she had enjoyed the confidences of both her brother, Humayun, and nephew, Akbar. From her account it is also apparent that she was an astute observer, well-versed with the intricacies of warfare and the intrigues of royal deal making. The first part of her story deals with Humayun's rule after her father's death and the travails of Humayun after his defeat. She had written little about her father Babur, as she was only aged eight when he died. However, there are anecdotes and stories she had heard about him from her companions in the Mahal (harem) that she included in her account. The latter part also deals with life in the Mughal harem.

She recorded one light-hearted incident about Babur. He had minted a large gold coin, as he was fond of doing, after he established his kingdom in India. This heavy gold coin was sent to Kabul, with special instructions to play a practical joke on the court jester Asas, who had stayed behind in Kabul. Asas was to be blindfolded and the coin was to be hung around his neck. Asas was intrigued and worried about the heavy weight around his neck, not knowing what it was. However, when he realised that it was a gold coin, Asas jumped with joy and pranced around the room, repeatedly saying that no one shall ever take it from him.

Gulbadan Begum describes her father's death when her brother had fallen ill at the age of 22. She tells that Babur was depressed to see his son seriously ill and dying. For four days he circumambulated the bed of his son repeatedly, praying to Allah, begging to be taken to the eternal world in his son's place. As if by miracle, his prayers were answered. The son recovered and the 47-year-old father died soon after.

Soon after his exile, Humayun had seen and fallen in love with a 13-year-old girl named Hamida Banu the niece of Shah Husain Mirza. At first she refused to come to see the Emperor, who was much older than her. Finally she was advised by the other women of the harem to reconsider, and she consented to marry the Emperor. Two years later, in 1542, she bore Humayun a son named Akbar, the greatest of the Mughal rulers. Gulbadan Begum described the details of this incident and the marriage of Humayun and Hamida Banu with glee, and a hint of mischievousness in her manuscript.

Gulbadan also recorded the nomadic life style of Mughal women. Her younger days were spent in the typical style of the peripatetic Mughal family, wandering between Kabul, Agra and Lahore. During Humayun's exile the problem was further exaggerated. She had to live in Kabul with one of her step brothers, who later tried to recruit her husband to join him against Humayun. Gulbadan Begum persuaded her husband not to do so. He, however, did so during her nephew's reign and, along with his son, was defeated and was expelled from court and from her presence for the rest of his life. He was not even allowed to be buried next to her. His grave is in one corner of the main quadrangle in which she is buried.

If Gulbadan Begum wrote about the death of Humayun, when he tumbled down the steps in Purana Qila in Delhi, it has been lost. The manuscript seems to end abruptly in the year 1552, four years before the death of Humayun. It ends in mid-sentence, describing the blinding of Kamran Mirza. As we know that Gulbadan Begum had received the directive to write the story of Humayun's rule by Akbar, long after the death of Humayun, it is reasonable to believe that the only available manuscript is an incomplete version of her writing. It is also believed that Akbar asked his aunt to write down from her memory so that Abul Fazl could use the information in his own writings about the Emperor Akbar.

The memoir had been lost for several centuries and what has been found is not well preserved, poorly bound with many pages missing. It also appears to be incomplete, with the last chapters missing. There must have been very few copies of the manuscript, and for this reason it did not receive the recognition it deserved.

A battered copy of the manuscript is kept in the British Library. Originally found by an Englishman, Colonel G. W. Hamilton. it was sold to the British Museum by his widow in 1868. Its existence was little known until 1901, when Annette S. Beveridge translated it into English (Beveridge affectionately called her 'Princess Rosebody').[10][11]

Historian Dr. Rieu called it one of the most remarkable manuscripts in the collection of Colonel Hamilton (who had collected more than 1,000 manuscripts). A paperback edition of Beveridge's English translation was published in India in 2001.

Pradosh Chattopadhyay translated Humayun Nama into Bengali in 2006 and Chirayata Prokashan published the book.[12]

Pilgrimage to Mecca

Gulbadan Begum described in her memoir a pilgrimage she along with Salima Sultan Begum undertook to Mecca, a distance of 3,000 miles, crossing treacherous mountains and hostile deserts. Though they were of royal birth, the women of the harem were hardy and prepared to face hardships, especially since their lives were so intimately intertwined with the men and their fortunes. Gulbadan Begum stayed in Mecca for nearly four years and during her return a shipwreck in Aden kept her from returning to Agra for several months. She finally returned in 1582, seven years after she had set forth on her journey.

Akbar had provided for safe passage of his aunt on her Hajj and sent a noble as escort with several ladies in attendance. Lavish gifts were packed with her entourage that could be used as alms. Her arrival in Mecca caused quite a stir and people from as far as Syria and Asia Minor swarmed to Mecca to get a share of the bounty.

Later life

When she was 70, her name is mentioned with that of Muhammad-yar, a son of her daughter, who left the court in disgrace. She with Hamida, received royal gifts of money and jewels on the occasion of the New Year by Akbar.

Her charities were large, and it is said of her that she added day unto day in the endeavor to please God, and this by succoring the poor and needy.

When she was 80, in February 1603, her departure was heralded by a few days of fever. Hamida was with her to the end and watched her last hours. As she lay with closed eyes, Hamida Banu Begum spoke to her by the long-used name of affection, "Jiu!" (live or May you Live). There was no response. Then, "Gul-badan!" The dying woman opened her eyes, quoted the verse, "I die—may you live!" and died.

Akbar helped to carry her bier some distance, and for her soul's repose made lavish gifts and did good works. He will have joined in the silent prayer for her soul before committal of her body to the earth, and if no son were there, he, as a near kinsman, may have answered the Imam's injunction to resignation: "It is the will of God."

It is said that for the two years after her death, Akbar lamented constantly that he missed his favorite aunt, until he died in 1605.

Gulbadan was also said to have been a poet, fluent in both Persian and Turkish. None of her poems have survived. However, there are references to two verses and a quaseeda written by her by the Emperor Bahadur Shah Zafar in his collection of verses as well as some references by Mir Taqi Mir.

For much of history, the manuscript of Gulbadan Begum remained in obscurity. There is little mention of it in contemporary literature of other Mughal writers, especially the authors who chronicled Akbar’s rule. Yet, the little-known account of Gulbadan Begum is an important document for historians, with its window into a woman’s perspective from inside the Mughal harem.

In popular culture

- Gulbadan Begum is a principal character in Salman Rushdie's novel The Enchantress of Florence (2008).[13]

References

- ↑ Aftab, Tahera (2008). Inscribing South Asian Muslim women : an annotated bibliography & research guide ([Online-Ausg.]. ed.). Leiden: Brill. p. 8. ISBN 9789004158498.

- ↑ Faruqui, Munis D. (2012). Princes of the Mughal Empire, 1504-1719. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 251. ISBN 9781107022171.

- ↑ Ruggles, D. Fairchild (ed.) (2000). Women, patronage, and self-representation in Islamic societies. Albany, N.Y.: State University of New York Press. p. 121. ISBN 9780791444696.

{{cite book}}:|first1=has generic name (help) - ↑ Balabanlilar, Lisa (2015). Imperial Identity in the Mughal Empire: Memory and Dynastic Politics in Early Modern South and Central Asia. I.B.Tauris. p. 8. ISBN 9780857732460.

- ↑ Ruggles, D. Fairchild (ed.) (2000). Women, patronage, and self-representation in Islamic societies. Albany, N.Y.: State University of New York Press. p. 121. ISBN 9780791444696.

{{cite book}}:|first1=has generic name (help) - ↑ Schimmel, Annemarie (2004). The Empire of the Great Mughals: History, Art and Culture. Reaktion Books. p. 144.

- ↑ Balabanlilar, Lisa (2015). Imperial Identity in the Mughal Empire: Memory and Dynastic Politics in Early Modern South and Central Asia. I.B.Tauris. p. 8. ISBN 9780857732460.

- ↑ The Humayun Namah, by Gulbadan Begam, a study site by Deanna Ramsay

- ↑ "2. The Culture and Politics of Persian in Precolonial Hindustan", Literary Cultures in History, University of California Press, pp. 131–198, 31 December 2019, doi:10.1525/9780520926738-007, ISBN 978-0-520-92673-8, S2CID 226770775, retrieved 11 June 2021

- ↑ Beveridge, Annette Susannah (1898). Life and writings of Gulbadan Begam (Lady Rosebody). Calcutta. Retrieved 14 December 2017.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ↑ Begam, Gulbaden (1902). Beveridge, Annette Susannah (ed.). The history of Humāyūn (Humāyūn-nāma). London: Royal Asiatic Society. Retrieved 14 December 2017.

- ↑ ISBN 81-85696-66-7

- ↑ Rushdie, Salman (2008). Enchantress of Florence, The. London: Random House. ISBN 978-1407016498.

Bibliography

- Begum, Gulbadan; (tr. by Annette S. Beveridge) (1902). Humayun-nama :The history of Humayun. Royal Asiatic Society.

- Begam Gulbadam; Annette S. Beveridge (1902). The history of Humayun = Humayun-nama. Begam Gulbadam. pp. 249–. GGKEY:NDSD0TGDPA1.

- Humayun-Nama : The History of Humayun by Gul-Badan Begam. Translated by Annette S. Beveridge. New Delhi, Goodword, 2001, ISBN 81-87570-99-7.

- Rebecca Ruth Gould "How Gulbadan Remembered: The Book of Humāyūn as an Act of Representation," Early Modern Women: An Interdisciplinary Journal, Vol. 6, pp. 121–127, 2011

- Three Memoirs of Homayun. Volume One: Humáyunnáma and Tadhkiratu’l-wáqíát; Volume Two: Táríkh-i Humáyún, translated from the Persian by Wheeler Thackston. Bibliotheca Iranica/Intellectual Traditions Series, Hossein Ziai, Editor-in-Chief. Bilingual Edition, No. 11 (15 March 2009)

External links

- Complete text of Humayun Nama

- Begum, Gulbadan; (tr. by Annette S. Beveridge) (1902). Humayun-nama :The history of Humayun. Royal Asiatic Society.

- Selections from The Humayun Nama by Gulbadan Begam