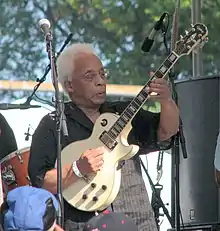

George Freeman | |

|---|---|

Freeman at the 2008 Chicago Jazz Festival | |

| Background information | |

| Born | April 10, 1927 Chicago, Illinois, U.S. |

| Genres | Jazz, soul jazz |

| Occupation(s) | Musician |

| Instrument(s) | Guitar |

| Years active | 1940s–present |

George Freeman (born April 10, 1927) is an American jazz guitarist and recording artist. He is known for his sophisticated technique, collaborations with high-profile performers, and notable presence in the jazz scene of Chicago, Illinois.[1] He is the younger brother of tenor saxophonist Von Freeman and drummer Eldridge "Bruz" Freeman, and the uncle of tenor saxophonist and trumpeter Chico Freeman.

Early life

Freeman was born on April 10, 1927, in Chicago, Illinois. His parents were amateur musicians—his father a trombonist and his mother a guitarist and singer.[2] His father, George Sr., was a Chicago police officer who regularly befriended musicians at the South Side clubs on his beat, most notably the Grand Terrace Ballroom. As a result, Louis Armstrong, Earl Hines, Fats Waller, and other foundational jazz musicians frequently visited the Freeman home.[3]

Freeman's siblings went on to become professional musicians. Bruz played drums, and Von the tenor saxophone. Freeman himself would come to play the guitar, inspired by his visits as a teenager to the Rhumboogie Cafe in the early 1940s. There, he saw T-Bone Walker play, and the crowd's ecstatic response to Walker motivated him to learn the guitar.[4]

Wind players such as Von and later Charlie Parker informed Freeman's basic approach to music.[4] He further refined his skills while attending DuSable High School, whose students included Von, Gene Ammons, Johnny Griffin, Red Holloway, Clifford Jordan, John Gilmore, Wilbur Ware, Dinah Washington, Sonny Cohn, Richard Davis, and other musicians.[5][6][7]

Career

During his teenage years, Freeman was invited to play with The Dukes of Swing, a band led by Eugene Wright.[8] Shortly after, wanting more opportunities to solo, Freeman started his own band, performing mainly at the ballroom of the Pershing Hotel at 64th and Cottage Grove. By 1946 Freeman was fronting Chicago's first modern-jazz bebop band, a band that included alto saxophonist Henry Pryor, tenor saxophonist Alec Johnson, and trumpeter Robert Gay. Freeman-led bands also backed visiting musicians such as Coleman Hawkins[9] and Lester Young.[10] During the engagement with Young, the saxophonist called for his recently-recorded song D.B. Blues. In response, Freeman surprised Young by playing his solo note-for-note, a custom Freeman had previously cultivated with his Chicago audience.[11]

1947–1949: New York City

In 1947, shortly after his 20th birthday, Freeman traveled to New York with Johnny Griffin – a high school friend who previously had left Chicago to tour with the Lionel Hampton band – to join the band he was forming with trumpeter Joe Morris.[4] Over the next year, Freeman met and listened to notable artists in the bebop genre. He also gave a solo guitar concert in Philadelphia for an audience consisting of a young Fats Navarro and John Coltrane.[12]

Freeman made his first recordings with the Joe Morris Orchestra in late 1947, first on the Manor label,[13] and then on the fledgling Atlantic label.[14] The band's sound was a blend of R&B and jazz, which contrasted with Freeman's more eccentric, bebop-inspired style of playing. His extended solo feature on Boogie Woogie Joe, recorded in late 1947, has been described by one rock music writer as "...the first scintillating guitar workout in rock history."[15][16]

In December 1947, the Morris band recorded a song based on The Hulk, a blues composed by Freeman. For the Atlantic recording, it was renamed Lowe Groovin' , a title derived from the name of a Washington, D.C., disk jockey named Jackson Lowe.[14] When the record came out in 1948, the composition was credited on the label to Morris, not Freeman. Freeman quit the band and returned to Chicago in response.[17][16]

1950–1959: Collaborations with Charlie Parker and others

Upon his return, Freeman re-assumed his place in the Chicago music scene, often performing with his brothers at the Pershing Hotel. Highlights of this period were collaborations with Charlie Parker – twice in Chicago and once in Detroit – between 1950 and 1951.[18] During these performances, Parker developed a close musical and personal rapport with the Freemans. At one engagement, Von took George's tie and lent it to Parker. Parker never returned it and subsequently wore it in publicity photos, including one on the wall behind the stage at The Jazz Showcase in Chicago.[16] At another point, as a set was scheduled to begin while Freeman was still backstage, Parker rejected the pleas of the audience to start: "No, I'm not going to play anything until George gets back."[4]

An amateur recording of the Parker-Freeman performances in Chicago has been reissued multiple times.[19] In a 2003 release, music historian and annotator Loren Schoenberg said this about Freeman's playing: "There is virtually no precedent for the outrageously experimental music that George Freeman creates throughout this set.... His ... solo [on one tune] is unlike anything I have ever heard, and seems much closer to what John Scofield and Bill Frisell have brought to the jazz guitar in the '90s than to anything from his own contemporaries."[20]

Freeman remained in Chicago throughout the 1950s, but by 1959 he decided to tour again. He traveled the country with tenor saxophonist Sil Austin and vocalist Jackie Wilson, then with organist Wild Bill Davis, and finally with organist Richard "Groove" Holmes.[4]

1960–1979: Tours with Groove Holmes and Gene Ammons

Freeman spent most of the 1960s touring with Holmes. Freeman also was featured on Holmes' first record, Groove, alongside tenor saxophone player Ben Webster.[21] Another recording highlight with Holmes was The Groover!, which features Freeman's guitar work along with two of his own compositions.[22]

In 1969, tenor saxophonist Gene Ammons, having been released from incarceration on drug charges,[23] returned to Chicago and performed with old colleagues and high school classmates, including Freeman.[24] After their performances, Ammons asked Freeman to join him on the front line of a band he was forming. Freeman accepted[4] and would remain a featured member of the Ammons band, with a few interruptions, until Ammons' death from bone cancer in 1974.[25]

The Ammons-Freeman collaboration yielded several recordings, including The Black Cat, the title track of which was written by Freeman.[26] Ammons' admiration for Freeman's playing is revealed in a Down Beat interview conducted by jazz writer Leonard Feather. Ammons expressed a dislike for avant garde jazz music, and in response, Feather countered that Freeman's solos often fell into that category. Ammons responded: "I agree. But George does it in the realm of what's going on otherwise, as far as the rest of the rhythm and the whole situation, and it sounds good."[27]

Freeman's work during the Ammons years garnered acclaim. A 1971 Down Beat issue, entitled MASTERS OF JAZZ GUITAR, showcased Freeman's work along with that of Kenny Burrell and Jim Hall.[28] Other bandleaders who recognized Freeman's talents tried to pry him away from Ammons; most were unsuccessful, but Freeman did accept an offer to join organist Jimmy McGriff for a time. That partnership resulted in several albums, including Fly Dude from 1972, which features Freeman's guitar and compositions.[29] Another collaboration from this period was with drummer Buddy Rich and tenorist Illinois Jacquet, a collaboration that also produced an album.[30]

The 1970s also yielded Freeman's first album as leader, Birth Sign,[31] and several other recordings—including Franticdiagnosis from 1972,[32] New Improved Funk from 1973[33], and Man & Woman from 1974.[34]

1980–1999: Chicago and Rebellion

As the 1970s progressed, Freeman returned again to Chicago, which has remained the epicenter of his activities ever since.

Freeman resumed his work in local clubs, while at the same time, remained active in the recording studios. His appearance on Johnny Griffin's 1979 album Bush Dance is one of a number of highlights.[35] Another is Freeman's 1995 album Rebellion, on which his brother Von holds down the piano chair.[36]

2000–2020: Live Engagements and multiple recordings

The 2000s have been an active period for Freeman. He has recorded multiple albums under his own name, including 90 Going on Amazing, a 2005 album produced and recorded by Sirus XM Jazz Director Mark Ruffin and released by Blujazz in August 2017.[37] Freeman's other albums in this period have included collaborations with vocalist Kurt Elling,[38] tenorist (and brother Von's son) Chico Freeman,[39] and guitarist Mike Allemana.[40] In George The Bomb from 2019, Freeman teamed with blues singer and harmonica player Billy Branch.[41]

Freeman also has remained an active performer—playing in New York City[42] and Europe, but mostly, at home in Chicago.[43] Freeman has been a regular at the annual Chicago Jazz Festival, headlining with his brother Von, his nephew Chico (in 2015),[44] Mike Allemana (in 2017),[45] and Billy Branch (in 2019).[46][47] Freeman also has played engagements in jazz clubs and special events for the Jazz Institute of Chicago and the Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians.

Freeman's calendar of engagements was scrapped in March 2020 when the Covid-19 pandemic forced the cancellation of public events and the closing of jazz clubs. Freeman kept himself busy at home for the next year practicing and composing new music.[48]

2021–present: Everybody Say Yeah! and The Good Life

In April 2021, as Chicago clubs started reopening, Freeman returned to live performances with an engagement at The Green Mill Cocktail Lounge, just in time to celebrate his 94th Birthday on April 10.[49] Freeman remained active throughout 2021, headlining the Englewood Jazz Festival on September 18,[50] playing the Green Mill on October 1–2,[51] and opening the Blues Festival at The University of Chicago’s Logan Center on October 15.[52]

Freeman returned to the Green Mill in Chicago on April 8 and 9, 2022 for his annual birthday weekend.[53] In celebration of Freeman’s 95th birthday on April 10, 2022, Southport Records released Everybody Say Yeah!, a new compilation of recordings that documents 26 years of Freeman's music from the Chicago label's catalog, unreleased tracks, and a new recording of "Perfume" with fellow guitarist Mike Allemana.[11][54]

Freeman again entered the recording studio on May 7, 2022, leading a trio session with bassist Christian McBride and drummer Carl Allen.[55][56] And on June 13, 2022, Freeman led another trio session, this time supported by organist Joey DeFrancesco and drummer Lewis Nash.[56] These two recording sessions resulted in The Good Life, released by HighNote Records in June 2023.[57][58][56]

Freeman also continued with his schedule of live performances during 2023. Highlights included his annual birthday residency at the Green Mill in April[59] and an appearance with his nephew Chico at the Chicago Jazz Festival in August.[60] Freeman's activities and 2023 record release were featured in articles in DownBeat[61] and Guitar Player[62] and on The Today Show on NBC.[63]

Discography

As leader

- Introducing George Freeman Live with Charlie Earland Sitting In (Giant Step, 1971)

- Birth Sign (Delmark, 1972)

- Franticdiagnosis (Bam-Boo, 1972)

- Man & Woman (Groove Merchant, 1974)

- New Improved Funk (Groove Merchant, 1974)

- Rebellion (Southport, 1995)

- George Burns! (Southport, 1999)

- At Long Last George (Savant, 2001)

- All in the Family with Chico Freeman (Southport, 2015)

- Live at the Green Mill with Mike Allemana (Ears&eyes, 2017)

- 90 Going On Amazing (Blujazz, 2017)

- George the Bomb (Southport, 2019)

- Everybody Say Yeah! (Southport, 2022)

- The Good Life (HighNote, 2023)

As sideman

With Gene Ammons

- Hooray for John Coltrane, Gene Ammons (Session, 1970s)

- The Black Cat! (Prestige, 1971)

- You Talk That Talk! (Prestige, 1971)

- Swingin' the Jug (Roots, 1976)

- "Groove" (Pacific Jazz, 1961)

- Tell It Like It Tis (Pacific Jazz, 1966)

- Welcome Home (World Pacific Jazz, 1968)

- The Groover! (Prestige, 1968)

With Jimmy McGriff

- Fly Dude (Groove Merchant, 1972)

- Concert: Friday the 13th - Cook County Jail with Eli Lucky Thompson (Groove Merchant, 1973)

- Giants of the Organ Come Together with Richard "Groove" Holmes (Groove Merchant, 1973)

- 100% Pure Funk (LRC, 2001)

With others

- Mickey Fields, The Astonishing Mickey Fields (Edmar, 1960s)

- Charlie Parker, An Evening at Home with the Bird (Savoy, 1961)

- Les McCann, Oh Brother! (Fontana, 1964)

- Shirley Scott, Mystical Lady (Cadet, 1971)

- Buddy Rich, The Last Blues Album Volume 1 (Groove Merchant, 1974)

- Johnny Griffin, Bush Dance (Galaxy, 1979)

- Charlie Parker, One Night in Chicago (Savoy, 1980)

- Illinois Jacquet, Loot to Boot (LRC, 1991)

- Joe Morris, 1946–1949 (Classics, 2003)

- Red Holloway, Go Red Go! (Delmark, 2009)

References

- ↑ Reich, Howard (December 23, 2014). "Chicagoan of the Year in Jazz Music: George Freeman". Chicago Tribune. Archived from the original on December 7, 2022. Retrieved January 27, 2023.

- ↑ "Von Freeman dies at 88; jazz tenor saxophonist with singular sound". Obituaries. Los Angeles Times. August 17, 2012. Archived from the original on January 27, 2023.

- ↑ H. Reich, Von Freeman, Chicago jazz legend, dead at 88, Chicago Tribune, August 13, 2012

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 D. Morgenstern, George Freeman: Chicago Fire, Down Beat, June 10, 1971, pg. 14-15

- ↑ "Mayor Emanuel Honors DuSable High School as a Community Cornerstone, Presents Landmark Plaque to School Alumni and Ald. Pat Dowell (3rd)". www.chicago.gov. Retrieved June 28, 2023.

- ↑ "DuSable High School a landmark with jazz as catalyst". Chicago Tribune. December 18, 2012. Retrieved June 28, 2023.

- ↑ "List of Capt. Dyett's students at DuSable H.S." organissimo forums. March 31, 2015. Retrieved June 28, 2023.

- ↑ "CJM NOV | DEC 2015". CHICAGOJAZZ. Chicago Jazz Magazine. November–December 2015. Archived from the original on September 28, 2022. Retrieved March 3, 2023.

- ↑ O. Nosey, "Everybody Goes When the Wagon Comes", Chicago Defender (Nat'l Ed.), August 10, 1946, pg. 20

- ↑ A. Monroe, "Swinging The News", Chicago Defender (Nat'l Ed.), January 18, 1947, pg. 10

- 1 2 Whiteis, David (July 13, 2022). "Overdue Ovation: It's Happening Now for George Freeman". JazzTimes. Retrieved June 28, 2023.

- ↑ Jazz, All About (March 6, 2018). "Jazz news: 'A Toast To George Freeman' April 28, 2018 Special Guest Billy Branch, With Joanie Pallatto And Sparrow". All About Jazz. Retrieved June 28, 2023.

- ↑ "Johnny Griffin Discography". www.jazzdisco.org. Retrieved June 28, 2023.

- 1 2 "Atlantic Records Discography: 1947". www.jazzdisco.org. Retrieved June 28, 2023.

- ↑ Sampson (May 11, 2017). "Joe Morris: "Boogie Woogie Joe"". Spontaneous Lunacy. Archived from the original on October 21, 2021. Retrieved May 18, 2023.

- 1 2 3 Whiteis, David (July 13, 2022). "Overdue Ovation: It's Happening Now for George Freeman". JazzTimes. Madavor Media, LLC. Archived from the original on March 16, 2023. Retrieved May 18, 2023.

- ↑ Sampson (April 27, 2017). "Joe Morris: "Lowe Groovin"". Spontaneous Lunacy. Archived from the original on December 5, 2020. Retrieved May 18, 2023.

- ↑ "Turning 96, Chicago jazz guitarist George Freeman is still playing and about to release a new record". Chicago Sun-Times. April 4, 2023. Retrieved June 28, 2023.

- ↑ "CHARLIE PARKER - At The Pershing Ballroom Chicago 1950". JazzMusicArchives.com. Retrieved June 28, 2023.

- ↑ L. Schoenberg, Charlie Parker: The Complete Live Performances on Savoy, Notes pg. 53 (Savoy Jazz, 2003)

- ↑ Richard "Groove" Holmes. (1961). "Groove" [Album]. Pacific Jazz Records.

- ↑ Richard "Groove" Holmes. (1968). The Groover! [Album]. Prestige Records.

- ↑ New Drug Trial of Sax Star Ammons to Open, Chicago Defender (Daily Ed.), Nov. 13, 1962, pg. 1

- ↑ Gene Ammons Featured in Modern Jazz Showcase, Daily Chicago Defender (Big Weekend Ed.), Dec. 6, 1969, pg. 18

- ↑ "Gene Ammons Biography". musicianguide.com. Retrieved June 28, 2023.

- ↑ Gene Ammons. (1971). "The Black Cat!" [Album]. Prestige Records.

- ↑ L. Feather, The Rebirth of Gene Ammons, Down Beat, June 25, 1970, pg. 31

- ↑ Down Beat, June 10, 1971

- ↑ J. McGriff, Fly Dude, (Groove Merchant, 1972)

- ↑ B. Rich, The Last Blues Album Volume 1, Groove Merchant, 1974)

- ↑ George Freeman - Birth Sign Album Reviews, Songs & More | AllMusic, retrieved June 28, 2023

- ↑ G. Freeman, Birth Sign, (Delmark, 1972); G. Freeman, Franticdiagnosis, (Bam-Boo, 1972)

- ↑ George Freeman - New Improved Funk Album Reviews, Songs & More | AllMusic, retrieved June 28, 2023

- ↑ George Freeman - Man And Woman, 1974, retrieved June 28, 2023

- ↑ J. Griffin, Bush Dance, (Galaxy, 1979)

- ↑ G. Freeman, Rebellion, (Southport, 1995)

- ↑ Welcome to BluJazz.com, at www.blujazz.com

- ↑ G. Freeman, At Long Last George, (Savant, 2001)

- ↑ G. Freeman, All in the Family, (Southport, 2015)

- ↑ G. Freeman-M. Allemana, Live at the Green Mill, (Ears&eyes, 2017)

- ↑ G. Freeman, George The Bomb, (Southport, 2019)

- ↑ "Jazz Listings for Sept. 26-Oct. 2". The New York Times. September 25, 2014. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved June 28, 2023.

- ↑ "Chicagoan of the Year in Jazz Music: George Freeman". Chicago Tribune. December 23, 2014. Retrieved June 28, 2023.

- ↑ "2015 Chicago Jazz Fest: The good, the bad and the potential". Chicago Tribune. August 31, 2015. Retrieved June 28, 2023.

- ↑ Radio, WDCB Public. "Chicago Jazz Festival Festival 2017 - Full Lineup!". 90.9fm WDCB. Retrieved June 28, 2023.

- ↑ Corbett, John (August 27, 2019). "The Reader's guide to the 2019 Chicago Jazz Festival". Chicago Reader. Retrieved June 28, 2023.

- ↑ "CJF Archive". Jazz Institute of Chicago. Retrieved June 28, 2023.

- ↑ Weiss, Lynn. "George Freeman: 93 Going on Amazing". Big City Rhythm & Blues (Feb./March 2021): 22.

- ↑ greenmill. "(8pm – 11:30pm) GEORGE FREEMAN'S 94th BIRTHDAY BASH". Green Mill. Retrieved June 28, 2023.

- ↑ "Englewood Jazz Festival | Music in Chicago". Time Out Chicago. September 13, 2021. Retrieved June 28, 2023.

- ↑ greenmill. "(8pm – midnight) GEORGE FREEMAN QUARTET". Green Mill. Retrieved June 28, 2023.

- ↑ Johnson, Kevin (September 22, 2021). "George Freeman & Billy Branch @ Logan Center for the Arts, Chicago". delmark.com. Retrieved June 28, 2023.

- ↑ greenmill. "(8pm – midnight) GEORGE FREEMAN'S 95th BIRTHDAY BASH with special guest BERNARD "PRETTY" PURDIE". Green Mill. Retrieved June 29, 2023.

- ↑ Galil, J. R. Nelson, Leor (March 29, 2022). "Venerable jazz guitarist George Freeman celebrates 95 years with a new compilation". Chicago Reader. Retrieved June 28, 2023.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ "Today, Carl and I got to record a few tunes with the legendary guitarist, George Freeman. He told us stories about playing in NYC for the first time in 1947 with Johnny Griffin, a great Paul Chambers vs. Wilbur Ware story, but most of all, at age 95 (!!) he's still doin' it!". Twitter.com. Retrieved May 17, 2022.

- 1 2 3 "Guitarist George Freeman is still packing Chicago's jazz clubs". Chicago Tribune. April 5, 2023. Retrieved June 28, 2023.

- ↑ "The Good Life - George Freeman | Release Credits". AllMusic. Retrieved June 28, 2023.

- ↑ "George Freeman: "The Good Life" – Spontaneous Lunacy". Retrieved June 28, 2023.

- ↑ greenmill. "(8:30pm – midnight) GEORGE FREEMAN'S 96TH B-DAY BASH: TWO SETS at 8:30 and 10:30pm". Green Mill. Retrieved January 16, 2024.

- ↑ "Chico Freeman to honor his famous father, 'my hero' Von Freeman, at Chicago Jazz Festival". Chicago Sun-Times. August 28, 2023. Retrieved January 16, 2024.

- ↑ Mandel, H. (October 31, 2023). "George Freeman, Guitar Royalty at 96". DownBeat.

- ↑ published, Nikki O'Neil (January 12, 2024). ""Bird just grinned. He'd never heard a guitar played like that!" He saw T-Bone Walker, worked with Charlie Parker and uses a drawer-knob instead of a pick: Chicago jazz supremo George Freeman, 96, looks back over an epic career". Guitar Player. Retrieved January 16, 2024.

- ↑ "Meet the jazz guitarist still thrilling crowds at 96 years old". TODAY.com. Retrieved January 16, 2024.