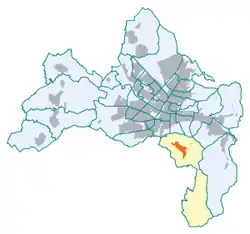

Günterstal | |

|---|---|

District | |

| |

| Coordinates: 47°57′55.5″N 07°51′26″E / 47.965417°N 7.85722°E | |

| District | Freiburg im Breisgau |

| State | Baden-Württemberg |

| Country | Germany |

| Incorporated | 1890 |

| Divisions | Oberdorf, Unterdorf |

| Area | |

| • Total | 15.10 km2 (5.83 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 330 m (1,080 ft) |

| Population (31st December 2017) | |

| • Total | 2,086 |

| • Density | 138/km2 (360/sq mi) |

| • Proportion of Foreign Nationalities | 14% |

| Postal code | 79100 |

| Area Code | 0761 |

| District number | 43 (Area: 430) |

| Website | www.freiburg.de |

The village Günterstal is the southernmost district of Freiburg im Breisgau. It is located in the so-called Bohrer-Tal area (where the craft of "Deichel-Bohrer", preindustrial wooden water pipes used for the distribution of water, took place) at the foot of the 1284 metre-high Schauinsland in the Günterstal district of the Black Forest. Due to this, Freiburg prides itself on being Germany's highest city. Günterstal has more than 2,000 inhabitants and is separated from Freiburg by a two-kilometre-wide meadow, the "Wonnhaldewiesen". The village was incorporated into Freiburg in 1890. The southern neighbouring municipality is Horben.

Günterstal is mentioned by name for the first time in a property deed from the year 804, at that time as "Gundherrerhusir" (Houses of Günther) in the march of Merzhausen. Around 300 years later the town reappeared under the name "Guntheristal". Around 1221, a nobleman, who according to tradition from the 18th century was called Günther of Kibenfels, gave his daughter Adelheid land in Günterstal.[1] There she built a small monastery (monastic attachment?). In a document from 1224, the nunnery was first mentioned in "Gunterstal". However, Günther von Kibenfels cannot be the town's namesake because "Günter" appeared in the place name much earlier.

The community around Adelheid joined the Cistercian order, which, especially since Bernhard of Clairvaux had also preached in Freiburg, sparked enthusiasm during the Crusade movement. After the death of Adelheid's father, his other possessions were also passed on to the monastic community, including the "Kibenfels" castle (on the Kybfelsen mountain). A property register from 1344 shows that the nunnery owned properties in 90 villages at the time, including today's city animal enclosure in Mundenhof. At this time, the municipality of Günterstaal comprised around 25 houses in addition to other properties. Noble families of the region such as the Küchlin, the Geben, and the Schnewlin made donations to the nunnery. Unlike in a so-called women's convent, their unmarried daughters entering the nunnery had to transfer all property to the nunnery and provide the abbesses, who also had a seat and voted in the Further Austrian Landstände (estates). In 1486 the nunnery was affected by a flood. The nunnery was also pillaged in periods of war and lost many possessions. In 1632 the nuns narrowly escaped the Swedes by fleeing to the Rheinau Abbey. In 1674 the nunnery, under Abbess Agnes von Greuth, released its subjects from servitude. After the economic situation of the nunnery had improved, in 1727 Abbess Maria Rosa von Neveu decided to replace the old nunnery building with a new building. In the period from 1728 to 1738, a completely new, baroque nunnery complex was built according to plans by Peter Thumb, under the abbess Maria Franziska Cajetana von Zurthannen, who came from the Black Forest and was as pious as she was energetic. Nothing of the abbey survived apart from the portal. Of the formerly rich furnishings of the abbey, only the following are still there: a Holy Blood relic that the Reichenau Abbey gave to the Cistercians in 1737, the associated monstrance from 1738 and the assumed baptismal font in Günterstal. Two side altars are now in the church of Buchenbach, the choir stalls in Kirchzarten, and the confessional in the church of the former Schuttern Abbey. The complex of nunnery buildings and their walls still characterise the town centre today. In 1806 the nunnery was dissolved by the order of Napoleon.

Günterstal after secularization

In 1812, the Mez company bought the monastery building and installed a factory there. For the inhabitants of Günterstal this was a historical break, for six hundred years the nunnery had influenced life in Günterstal. Günterstal is now a fully politically independent village. Although, it was not sustainable for to long, since an appropriate fortune is missing. As an "island" within the district of Freiburg, the people of Günterstal had to participate in the maintenance of the road network. In 1890 a town meeting decided to be incorporated into Freiburg. In 1892 the former abbey buildings were acquired by the Freiburg orphan foundation. After the incorporation into Freiburg, the transportation system improved, due to the construction of the tram line in 1901. The restaurant industry gets an upswing.

In 1829, the monastery is completely destroyed due to a fire. Initially, the entrepreneur family Hermann rebuilds part of the monastery buildings and established a brewery. From 1833 to 1834, the government of Baden constructs the present-day church, using parts of the baroque church facade and the headstone of the last abbes, and of one priest. By and by a wall is built and the church is newly equipped. The oldest piece is a madonna with a child at the entrance, dating back to the 14th century. From the former Church of the dissolved Tennenbach Abbey, the church receives an altar (table) and the (church) tabernacle, both constructed by Johann Michael Winterhalder (1706-1759). From the latter are also the cross on the right side wall and the pulpit. The stations of the cross, from 1863, were created by Wilhelm Dürr (the older), they were originally created for the Collegium Borromaeum in Freiburg. The colourful windows were created by the local class painters Helmle & Merzweiler, they were installed from 1885 to 1902. The grid behind the altar was installed in 1888. The reredos, side-altars and die steps of the pulpit were redesigned, by Petter Hillenbrand, an architect, during a renovation from 1998 to 2002. For the redesign, he used found objects of various origins.

Baden Revolution in Günterstal

During the Baden Revolution of 1848/49, Günterstal becomes the scene of a tragic battle. The neighboring village Horben is the operation base of Franz Sigel. Here his vanguard, led by Gustav Struve, they are met by the student Hermann Mors, who reports that Freiburg changed side on the 22 of April 1848 and now supports the partisans, and are waiting for the Freischärler (troops/irregulars) of Sigel. Disregarding the orders from Sigel, Struve takes his 400 men through the Günterstal towards the end of the valley. Here he is met with/by Baden Army. Struve hopes that the soldiers would change sides proved wrong. It comes to the Battle of Günterstal, the irregulars were put on the run and haunted till after Günterstal. In the battle, 20 irregulars and 3 soldiers died. Two of the soldiers are remembered with a memorial at the Jägerbrunnen, which still can be visited today.

Saint Lioba nunnery

The number of farms has declined. Instead, new country houses and villas have been built. At the northwest part of the village the "Villa Wohlgemuth", a villa in tuscany style, was constructed for Judge August Wohlgemuth from Müllheim. It was built from 1906 to 1913.[2] In 1927 the order of Saint Leoba took over the estate.

Waldhaus and Forstamt

In the autumn of 2008, a Waldhaus was opened at the Wohnhalde. Its task is to sensibilities and to educate school classes and the public about the ecosystem of the forest. They also plan to establish a renewable forest economy. Besides changing exhibitions there is a cafe which is open on Sundays and bank holidays.[3]

In close relation to the Waldhaus the laying of the stone for the new Forstamt starts in 2020. A Forstamt is an office that regulates and administers forest and forest economy. The "Stiftung Waldhaus" constructed a four-story high wooden house for 2.1 million euros. It is planned for the end of 2021, that the Forstamt moves in there. The new building is also an addition to the Waldhaus.[4]

In the closest district Wiehre, there is the Forest Experimental and Research Establishment of Baden Württemberg.

Verkehrsanbindung

Tram

Günterstal has been connected to the town centre by line 2 the Freiburg trams since 1901, which is operated by the Freiburger Verkehrs AG. Most of the rails run next to the "Schauinslandstraße" (Schauinsland street). In Günterstal the tram has three stops: Wiesenweg, Klosterplatz, and the end stop Dorfstraße. Until the end of 2014, when the extension of the cross-border line 8 of the Basel tram to Weil am Rhein was opened, this was the southernmost tram stop in Germany.[5] Now it is only the southernmost tram stop of any German transport company.

Buses

At the last stop of the tram, bus line 21 starts. During the day the bus calls at the valley station of the Schauinslandbahn and ends in Horben. The busses are running each 15 to 20 minutes to the cable car station, and each hour a bus calls at Horben.[6]

_1_ShiftN.jpg.webp)

.jpg.webp)

Hitchhikers' benches

Since 2019, there are two ride sharing benches in Güntertal. People who don't have a car, can sit there and wait for someone to pick them up. One is located at the last stop of the tram line and the other one is located at the southern entrance of Güntertal in the direction to Freiburg.[7]

Ortsbeschreibung

The district can be divided into Oberdorf, the southern part, and Unterdorf, the northern part, which faces the city. The border passes through the Maximilian-Kobe-Weg to the end tram stop and then runs along the Kuenzersteige.

Oberdorf

In the Oberdorf there are many villas and comfortable one Single-family detached homes. There are also

- Günterstäler pond

- the forest restaurant St. Valentin

Unterdorf

The Unterdorf is located closer to the city of Freiburg. In the 2010 years two bakeries had to close down.[8][9] The next supermarket is located in the Lorettostraße in Wiehre District.

More important buildings and institutions:

- the Günterstäler Gate, which used to be the entrance to the monastery

- the nun monastery "St. Lioba" (former Villa Wohlgemuth)

- the catholic Günterstal Abbey Church (Liebfrauenkirche) with an incorporated graveyard where many famous people are buried.

- the Protestant "Matthias-Claudius-chapel"

- the school building, which is a special education center with a focus on cognitive development, including a multipurpose hall

- a day nursery [10]

- different restaurants with normal to more sophisticated cuisine. At the restaurant Kybelsen there is a memorial plate for Edith Stein, who used to go there often.

- Coffeeshop with roast house[11]

- a petrol station

- a playground with a barbeque station

- the youth group Günterstal

Nature and landscape

_5082.jpg.webp)

The Russian writer Maxim Gorky, who lived in Günterstal in 1923, wrote about the landscape the following: "We live in a beautiful, green valley near Freiburg. We intend to stay here over the winter. The vegetation here is very interesting, not only because of the colours, but due to its shape: thuja, cypress, and different pine trees. its a mild, mountainous landscape."

The tallest tree in Germany

The tallest tree in Germany is in Mühlwald, a part of the Arboretum Freiburg-Günterstal,[12] a Douglas fir with a trunk circumference of 300 cm at the base, and a height of around 65 metres.[13] It was given the name Waldtraut vom Mühlwald 47°57′12″N 7°51′40″E / 47.953365°N 7.861127°E. In August 2008, the Eberdach Douglas fir was relegated to second place. The measurements of both trees were taken by a measurement team from the Geodetic Institute of the University of Karlsruhe. The measurement in March 2017, commissioned by the municipal forestry office, resulted in a height of 66.581 m.[14] The measurement from 19 November 2019 resulted in 67.18 m.[15]

Flood prevention

After years of planning and arguments the state of Freiburg promised a subsidy of 8.8 million euros for the construction of a 13.5 metre-high, 275 metre-long, and up to 80 metre-wide embankment dam in the Bohrertal to Horben boundary. A Horben farmer, whose fields were mainly affected, had complained to the Administrative Court in Mannheim against the planning approval decision of the city, which approved the dam in Horben. Nature conservation associations and Freiburg citizens' associations had also raised large objections to the Bohrertal dam. After the city made replacement land available to the Horben farmer, the legal dispute ended. There are also plans to increase the height of the existing flood control reservoir on the Breitmatte by two metres between the districts of Günterstal and Wiehre. The Mittel- and Unterwiehre citizens' association also resisted this, but no legal steps were taken against it. The ground-breaking for the Bohrertal dam took place in February 2020, and construction on the Breitmatte should begin in the summer. From the end of 2022, not only should the existing Freiburg districts be protected from a flood of the century by this 19.5-million-euro project, but they are also a prerequisite for the construction of the planned Dietenbach district.[16][17]

Famous persons

- Sepp Allgeier (1895–1968), cameraman and photographer, was laid to rest in the cemetery of Günterstal.

- Jonas Cohn (1869–1947), a German philosopher and educator, lived in Günterstal.

- Richard Engelmann (1868–1966), sculptor, buried in the cemetery of Günterstal.

- Hans Filbinger (1913–2007), Ministerpräsident, lived in Günterstal for many years, where he died and was buried in the cemetery.

- Hermann Flamm (1871–1915), historian and archivist, born in Günterstal.

- Maria Föhrenbach (1883–1961), founder of the female order of the Benedictines of saint Leoba OSB, is buried on the nunnery cemetery.

- Svetlana Geier (1923–2010), a famous literary translator, lived in Günterstal, where she died.

- Hans von Geyer zu Lauf (1895–1959), a German painter, was laid to rest in Günterstal.

- Maxim Gorky (1868–1936), a Russian writer, lived here in 1923 for a few months with his lover Moura Budberg.

- Rudolf Haufe (1903–1971), founder of the Haufe Lexware publisher, was buried in the cemetery.

- Edmund Husserl (1859–1938), philosopher; his ashes are interred in the cemetery.

- Wolfgang Kirchgässner (1928–2014), Auxiliary bishop of Freiburger from 1979 til 1998, lived in the monastery of St. Lioba.

- Friedrich Rinne (1863–1933), Mineralogist, buried in the cemetery of Günterstal.

- Lutz Röhrich (1922–2006), folklorist and narrative researcher, the first professor of the chair of Volkskunde at the University of Freiburg, lived in Günterstal until his death and was laid to rest there as well.

- Carl Schuster(1854–1925), German architekt und painter. Died in Günterstal. (Not to be confused with the American art historian Carl Schuster)

- Edith Stein (Saint Teresia Benedicta a Cruce, 1891–1942), was a philosopher and later catholic nun, canonized by Pope John Paul II and was admitted/appointed as a patron saints of Europe on the 11 October 1998. She lived in Günterstal in 1916, 1929, and 1931/32.

- Hans Thieme (1906–2000), legal historian, buried in the Güntersthal cemetery.

- Hildegardis Wulff (1896–1961), one of the founders of the female order of Benedict OSB of Saint Lioba, is laid to rest in the nunnery cemetery.

- Ernst Zermelo (1871–1953), Mathematician, buired on the Günterstal cemetery.

Literature

- Josef Bader: Die Schicksale des ehemaligen Frauenstifts Güntersthal bei Freiburg i. Br. In: Freiburger Diözesan-Archiv Band 5, 1870, S. 119–206 (Digitalisat).

- Ernst Dreher: Günterstal. Seine Geschichte von den Anfängen bis zur Klosterauflösung im Jahre 1806. Die Gemeinde Günterstal zwischen 1806 und 1830. Lahr, o. J. ISBN 3-9801383-3-X.

- Ernst Dreher: Die Gemeinde Günterstal zwischen 1806 und 1830 in: Schau-ins-Land: Jahresheft des Breisgau-Geschichtsvereins Schauinsland, Band 114, Freiburg im Breisgau 1995, S. 135–161 (Digitalisat).

- Ernst Dreher: Die Gemeinde Günterstal von 1806 bis 1830 (2. Teil). in: Schau-ins-Land: Jahresheft des Breisgau-Geschichtsvereins Schauinsland, Band 116, Freiburg im Breisgau 1997, S. 253–281 (Digitalisat).

- Karin Groll-Jörger: Günterstal Band 1: Von der Säkularisation bis zur Eingemeindung 1806–1890, Freiburg 2013, ISBN 978-3-935737-26-5.

- Karin Groll-Jörger: Günterstal und seine Matten im Spiegel der Geschichte. Eine Kulturlandschaft und ihre Entwicklung, Freiburg 2016, ISBN 978-3-935737-67-8.

- Karin Groll-Jörger: Der Wurf des Teufels. Von Wundern, Sagen und Märchen in und um Freiburg-Günterstal. Freiburg 2016. ISBN 978-3-935737-68-5

References

- ↑ Josef Bader: Günthersthal. In: August Schnezler: Badisches Sagen-Buch, I. Creuzbauer und Kasper, Karlsruhe 1846, S. 387–388. (Wikisource)

- ↑ Hans Sigmund (2016-08-15). "Freiburg: Wiedersehen: Villa Wohlgemuth in Günterstal". Badische Zeitung. Retrieved 2016-08-15.

- ↑ "Home - Waldhaus.de". Retrieved 2020-12-10.

- ↑ "Heute war Spatenstich für den Neubau des Forstamtes - www.freiburg.de - Rathaus und Service/Presse/Pressemitteilungen". 2020-12-10. Retrieved 2020-12-10.

- ↑ rm (2014-10-18). "Südwest: BZ-Porträt: Mit der Tram über die Landesgrenze". Badische Zeitung. Retrieved 2016-08-07.

- ↑ "Linienfahrpläne: Freiburger Verkehrs AG". Retrieved 2016-08-15.

- ↑ Jule Arwinski (2019-08-22). "In Freiburg-Günterstal stehen zwei Mitfahrerbänke, aber niemand hält an". Badische Zeitung. Retrieved 2019-08-23.

- ↑ Bettina Gröber (2015-11-27). "Das "Café Hornstein" ist nun Geschichte". Badische Zeitung. Retrieved 2019-02-10.

- ↑ Anja Bochtler (2017-03-31). "Orsverein Günterstal diskutierte über Infrastruktur". Badische Zeitung. Retrieved 2019-02-10.

- ↑ Bettina Gröber (2016-08-31). "Ins ehemalige "Café Hornstein" zieht jetzt eine Natur-Kita ein". Badische Zeitung. Retrieved 2019-02-10.

- ↑ Felix Klingel (2018-07-19). "In Günterstal hat ein Spezialitäten-Café mit eigener Rösterei aufgemacht". Badische Zeitung. Retrieved 2019-02-10.

- ↑ Claudia Füßler: Der Herr über den Traum aller Förster. In: Zeit Online, 24 November 2011, retrieved 15 September 2020.

- ↑ Jetzt ist es amtlich: Deutschlands höchster Baum steht in Freiburg

- ↑ Simone Höhl: Freiburgs Waldtraut ist der höchste Baum Deutschlands. Badische Zeitung, 21 March 2017; retrieved 5 April 2018.

- ↑ Mit Waltraut auf dem Holzweg, Anita Fertl, Badische Zeitung, 21 June 2020, retrieved 22 June 2020.

- ↑ Jelka Louisa Beule (2019-08-01). "Bauarbeiten für Hochwasserdamm im Bohrertal bei Freiburg starten im Herbst". Badische Zeitung. Retrieved 2019-08-06.

- ↑ Simone Lutz (2020-02-07). "Spatenstich für das umstrittenste Projekt des Freiburger Hochwasserschutzes". Badische Zeitung. Retrieved 2020-02-09.

External links

- Stadt Freiburg im Breisgau

- Kloster St. Lioba - Benediktinerinnen

- Weitere Informationen zu Günterstal

- Bilder Günterstals zur heutigen Zeit

- Bilder Günterstals zur Geschichte des Dorfes

- Ortsverein Günterstal

- Jugend Günterstal

- Zisterzienserinnenabtei Günterstal in the data bank "Abbeys in Baden-Württemberg" (Klöster in Baden-Württemberg) of the Baden-Württemberg State Archives

- Eintrag auf Landeskunde entdecken online leobw