The environment of the United States comprises diverse biotas, climates, and geologies. This diversity leads to a number of different distinct regions and geographies in which human communities live. This includes a rich variety of species of animals, fungi, plants and other organisms.

Because of the strong forces of economic exploitation and industrialization, humans have had deep effects on the ecosystems of the United States, resulting in a number of environmental issues.

Since awareness of these issues emerged in the 1970s, environmental regulations and a growing environmental movement, including both climate movement and the environmental justice movement have emerged to respond to the various threats to the environment. These movements are intertwined with a long history of conservation, starting in the early 19th century, that has resulted in a robust network of protected areas, including 28.8% of land managed by the Federal government.

Biota

Animals

There are about 21,717 different species of native plants and animals in the United States. More than 400 mammal, 700 bird, 500 reptile and amphibian, and 90,000 insect species have been documented.[1] Wetlands, such as the Florida Everglades, are the base for much of this diversity. There are over 140,000 invertebrates in the United States which is constantly growing as researchers identify more species. Fish are the largest group of animal species, with over one thousand counted so far. About 13,000 species are added to the list of known organisms each year.[2]

Fungi

Around 14,000 species of fungi were listed by Farr, Bills, Chamuris and Rossman in 1989.[3] Still, this list only included terrestrial species. It did not include lichen-forming fungi, fungi on dung, freshwater fungi, marine fungi or many other categories. Fungi are essential to the survival of many groups of organisms.

Plants

With habitats ranging from tropical to Arctic, U.S. plant life is very diverse. The country has more than 17,000 identified native species of flora, including 5,000 in California (home to the tallest, the most massive, and the oldest trees in the world).[4] Three quarters of the United States species consist of flowering plants.

Human impacts on biota

The country's ecosystems include thousands of nonnative exotic species that often harm indigenous communities of living things. Many indigenous species became extinct soon after first human settlement, including the North American megafauna; others have become nearly extinct since European settlement, among them the American bison and California condor.[5] Many plants and animals have declined dramatically as a result of massive conversion and other human activity.

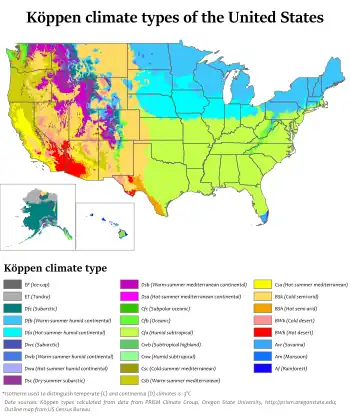

Climate

The U.S. climate is temperate in most areas, tropical in Hawaii and southern Florida, polar in Alaska, semiarid in the Great Plains west of the 100th meridian, Mediterranean in coastal California and arid in the Great Basin. Its comparatively generous climate contributed (in part) to the country's rise as a world power, with infrequent severe drought in the major agricultural regions, a general lack of widespread flooding, and a mainly temperate climate that receives adequate precipitation.

Following World War II, cities in the southern and western region experienced an economic and population boom. The population growth in the Southwest, has strained water and power resources, with water diverted from agricultural uses to major population centers, such as Las Vegas and Los Angeles. According to the California Department of Water Resources, if more supplies are not found by 2020, residents will face a water shortfall nearly as great as the amount consumed today.[6]

The United States mainland contains a total of seven distinct regional climates. Those include high elevation Northwestern region, the Pacific Northwest, the High plains, Midwest/Ohio valley/New England, Mid Atlantic/Southeast, Southern region, and Southwestern region. Each region contains different states and has their own climate and temperatures throughout the year.[7]

Geology

The richly textured landscape of the United States is a product of the dueling forces of plate tectonics, weathering and erosion. Over the 4.5 billion-year history of the Earth, tectonic upheavals and colliding plates have raised great mountain ranges while the forces of erosion and weathering worked to tear them down. Even after many millions of years, records of Earth's great upheavals remain imprinted as textural variations and surface patterns that define distinctive landscapes or provinces.[8]

The diversity of the landscapes of the United States can be easily seen on the shaded relief image to the right. The stark contrast between the ‘rough' texture of the western US and the ‘smooth' central and eastern regions is immediately apparent. Differences in roughness (topographic relief) result from a variety of processes acting on the underlying rock. The plate tectonic history of a region strongly influences the rock type and structure exposed at the surface, but differing rates of erosion that accompany changing climates can also have profound impacts on the land.[8]Environmental law and conservation

The nation's major environmental laws were enacted between 1969 and 1980:

- National Environmental Policy Act (1969)

- Clean Air Act (1970)

- Federal Insecticide, Fungicide, and Rodenticide Act (1972)

- Clean Water Act (1972)

- Endangered Species Act (1973)

- Safe Drinking Water Act (1974)

- Resource Conservation and Recovery Act (1976)

- Toxic Substances Control Act (1976)

- "Superfund" Act (1980)

The Endangered Species Act of protects threatened and endangered species and their habitats, which are monitored by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.

Protected areas

The United States maintains national parks as well as other preservation areas, such as the Florida Everglades. There are more than 400 protected sites spread across 84 million acres but very few are large enough to contain ecosystems.

In 1872, the world's first national park was established at Yellowstone. Another fifty-seven national parks and hundreds of other federally managed parks and forests have since been formed.[9] Wilderness areas have been established around the country to ensure long-term protection of pristine habitats. Altogether, the U.S. government regulates 1,020,779 square miles (2,643,807 km2), 28.8% of the country's total land area.[10] Protected parks and forestland constitute most of this. As of March 2004, approximately 16% of public land under Bureau of Land Management administration was being leased for commercial oil and natural gas drilling;[11] public land is also leased for mining and cattle ranching.

Environmental issues

Climate change

.png.webp)

Climate change has led to the United States warming by 2.6 °F (1.4 °C) since 1970.[18] The climate of the United States is shifting in ways that are widespread and varied between regions.[19][20] From 2010 to 2019, the United States experienced its hottest decade on record.[21] Extreme weather events, invasive species, floods and droughts are increasing.[22][23][24] Climate change's impacts on tropical cyclones and sea level rise also affects regions of the country.

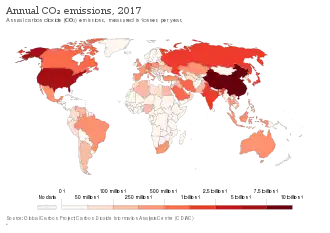

Cumulatively since 1850, the U.S. has emitted a larger share than any country of the greenhouse gases causing current climate change, with some 20% of the global total of carbon dioxide alone.[25] Current US emissions per person are among the largest in the world.[26] Various state and federal climate change policies have been introduced, and the US has ratified the Paris Agreement despite temporarily withdrawing. In 2021, the country set a target of halving its annual greenhouse gas emissions by 2030.[27]

Climate change is having considerable impacts on the environment and society of the United States. This includes implications for agriculture, the economy, human health and indigenous peoples, and it is seen as a national security threat.[28] States that emit more carbon dioxide per person and introduce policies to oppose climate action are generally experiencing greater impacts.[29][30] 2020 was a historic year for billion-dollar weather and climate disasters in U.S.[31]

Although historically a non-partisan issue, climate change has become controversial and politically divisive in the country in recent decades. Oil companies have known since the 1970s that burning oil and gas could cause global warming but nevertheless funded deniers for years.[32][33] Despite the support of a clear scientific consensus, as recently as 2021 one-third of Americans deny that human-caused climate change exists[34] although the majority are concerned or alarmed about the issue.[35]Conservation

Conservation in the United States can be traced back to the 19th century with the formation of the first National Park. Conservation generally refers to the act of consciously and efficiently using land and/or its natural resources. This can be in the form of setting aside tracts of land for protection from hunting or urban development, or it can take the form of using less resources such as metal, water, or coal. Usually, this process of conservation occurs through or after legislation on local or national levels is passed.

Conservation in the United States, as a movement, began with the American sportsmen who came to the realization that wanton waste of wildlife and their habitat had led to the extinction of some species, while other species were at risk. John Muir and the Sierra Club started the modern movement, history shows that the Boone and Crockett Club, formed by Theodore Roosevelt, spearheaded conservation in the United States.[36]

While conservation and preservation both have similar definitions and broad categories, preservation in the natural and environmental scope refers to the action of keeping areas the way they are and trying to dissuade the use of its resources; conservation may employ similar methods but does not call for the diminishing of resource use but rather calls for a responsible way of going about it. A distinction between Sierra Club and Boone and Crockett Club is that Sierra Club was and is considered a preservationist organization whereas Boone and Crockett Club endorses conservation, simply defined as an "intelligent use of natural resources."[37]

See also

Environment portal

Environment portal United States portal

United States portal- Ecotourism in the United States

- Great Plains Population and Environment Data Series

- List of Superfund sites in the United States

- National Conservation Exposition

- National Environmental Information Exchange Network

- Timeline of major U.S. environmental and occupational health regulation

References

- ↑ Laroe, Edward T. (1995). "Our Living Resources". U.S. Dept. of the Interior, National Biological Service. doi:10.5962/bhl.title.4172.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ↑ Number of Native Species in United States

- ↑ Farr, D.F, Bills, G.F., Chamuris, G.P. and Rossman, A.Y. "Fungi on Plants and Plant Products in the United States". 1252 pp., APS Press, St Paul Minnesota, USA, 1989

- ↑ Morse, L. E., Kartesz, J. T., & Kutner, L. S. (1995). "Native vascular plants". Our Living Resources: a report to the nation on the distribution, abundance, and health of US plants, animals and ecosystems. Washington, DC: US Department of the Interior, National Biological Service. pp. 205–209.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ "Pleistocene Megafauna Extinctions". Cpluhna.nau.edu. Archived from the original on March 8, 2010. Retrieved January 31, 2010.

- ↑ A World Without Water -Global Policy Forum- NGOs Archived July 12, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Regional Climates in the United States March 21, 2018 USA Today

- 1 2

This article incorporates public domain material from "Geologic Provinces of the United States: Records of an Active Earth". USGS Geology in the Parks. United States Geological Survey. Archived from the original on June 25, 2013. Retrieved May 12, 2013.

This article incorporates public domain material from "Geologic Provinces of the United States: Records of an Active Earth". USGS Geology in the Parks. United States Geological Survey. Archived from the original on June 25, 2013. Retrieved May 12, 2013. - ↑ Baker, Maverick (2016). "10 Ways Humans Impact the Environment". interestingengineeering.com. Retrieved March 24, 2018.

- ↑ "Federal Land and Buildings Ownership" (PDF). Republican Study Committee. May 19, 2005. Archived from the original (PDF) on May 24, 2010. Retrieved June 13, 2006.

- ↑ "Abuse of Trust: A Brief History of the Bush Administration's Disastrous Oil and Gas Development Policies in the Rocky Mountain West". Wilderness Society. May 28, 2007. Retrieved June 11, 2007.

- ↑ ● "Territorial (MtCO2)". GlobalCarbonAtlas.org. Retrieved December 30, 2021. (choose "Chart view"; use download link)

● Data for 2020 is also presented in Popovich, Nadja; Plumer, Brad (November 12, 2021). "Who Has The Most Historical Responsibility for Climate Change?". The New York Times. Archived from the original on December 29, 2021.

● Source for country populations: "List of the populations of the world's countries, dependencies, and territories". britannica.com. Encyclopedia Britannica. - ↑ EPA, OA, US (January 12, 2016). "Global Greenhouse Gas Emissions Data | US EPA". US EPA. Retrieved June 13, 2018.

- ↑ "United States: Climate Policy". Encyclopedia.com. Retrieved November 1, 2020.

- ↑ McGrath, Matt (October 20, 2020). "US election 2020: What the results will mean for climate change". BBC. Retrieved November 1, 2020.

- ↑ "Climate Change Indicators: U.S. and Global Temperature". EPA.gov. Environmental Protection Agency. 2021. Archived from the original on December 30, 2021.

(FIg. 3) EPA's data source: NOAA (National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration). 2021. Climate at a glance. Accessed February 2021. www.ncdc.noaa.gov/cag.

(Direct link to graphic; archive) - ↑ Hawkins, Ed (2023). "Temperature change in the USA". ShowYourStripes.info. Archived from the original on February 25, 2023. — Based on warming stripes concept.

- ↑ "Earth Day: U.S. Warming Rankings". Climate Central. April 20, 2022. Archived from the original on April 20, 2022.

- ↑ "Sixth Assessment Report". www.ipcc.ch. Retrieved August 20, 2021.

- ↑ Heidari, Hadi; Arabi, Mazdak; Warziniack, Travis; Kao, Shih-Chieh (2020). "Assessing Shifts in Regional Hydroclimatic Conditions of U.S. River Basins in Response to Climate Change over the 21st Century". Earth's Future. 8 (10): e2020EF001657. Bibcode:2020EaFut...801657H. doi:10.1029/2020EF001657. ISSN 2328-4277. S2CID 225251957.

- ↑ US EPA, OAR (June 27, 2016). "Climate Change Indicators: U.S. and Global Temperature". www.epa.gov. Retrieved August 20, 2021.

- ↑ Heidari, Hadi; Arabi, Mazdak; Ghanbari, Mahshid; Warziniack, Travis (June 2020). "A Probabilistic Approach for Characterization of Sub-Annual Socioeconomic Drought Intensity-Duration-Frequency (IDF) Relationships in a Changing Environment". Water. 12 (6): 1522. doi:10.3390/w12061522.

- ↑ US EPA, OAR (November 6, 2015). "Climate Change Indicators in the United States". www.epa.gov. Retrieved July 29, 2022.

- ↑ Casagr, Tina (February 16, 2022). "Climate Change and Invasive Species - NISAW". Retrieved July 29, 2022.

- ↑ "Analysis: Which countries are historically responsible for climate change?". Carbon Brief. October 5, 2021. Archived from the original on December 23, 2021. Retrieved December 30, 2021.

- ↑ www.climatewatchdata.org Archived 2021-06-24 at the Wayback Machine, at Calculations select per capita.

- ↑ "New momentum reduces emissions gap, but huge gap remains - analysis". Climate Action Tracker. Retrieved April 27, 2021.

- ↑ "Climate Change and US National Security: Past, Present, Future". atlanticcouncil.org. Atlantic Council. March 29, 2016. Retrieved September 21, 2016.

- ↑ Tollefson, Jeff (February 12, 2019). "US climate costs will be highest in Republican strongholds". Nature. doi:10.1038/d41586-019-00327-2. S2CID 188147110. Retrieved October 28, 2020.

- ↑ "States Blocking Climate Action Hold Residents Who Suffer the Most From Climate Impacts". Climate Nexus, Ecowatch. October 29, 2019. Retrieved October 31, 2019.

- ↑ Smith, Adam B.; NOAA National Centers For Environmental Information (December 2020). "Billion-Dollar Weather and Climate Disasters: Overview / 2020 in Progress". NCDC.NOAA. National Centers for Environmental Information (NCDC, part of NOAA). doi:10.25921/stkw-7w73. Archived from the original on December 10, 2020. Retrieved December 11, 2020. and "Contiguous U.S. ranked fifth warmest during 2020; Alaska experienced its coldest year since 2012 / 2020 Billion Dollar Disasters and Other Notable Extremes". NCEI.NOAA.gov. NOAA. January 2021. Archived from the original on January 8, 2021. For 2021 data: "Calculating the Cost of Weather and Climate Disasters / Seven things to know about NCEI's U.S. billion-dollar disasters data". ncei.noaa.gov. October 6, 2017. Archived from the original on January 11, 2022.

- ↑ Egan, Timothy (November 5, 2015). "Exxon Mobil and the G.O.P.: Fossil Fools". The New York Times. Retrieved November 9, 2015.

- ↑ Goldenberg, Suzanne (July 8, 2015). "Exxon knew of climate change in 1981, email says – but it funded deniers for 27 more years". The Guardian. Retrieved November 9, 2015.

- ↑ "A third of Americans deny human-caused climate change exists". The Economist. July 8, 2021. ISSN 0013-0613. Retrieved December 30, 2021.

- ↑ Yang, Maya (January 13, 2021). "Six in 10 Americans 'alarmed' or 'concerned' about climate change – study". The Guardian. Archived from the original on January 14, 2022.

- ↑ Reiger, John F. (2001). American Sportsmen and the Origins of Conservation (Third ed.). Oregon State University Press. pp. 4, 150–74, 180–87, 165–71. ISBN 978-0-87071-487-0.

- ↑ Roosevelt, Theodore. "Famous Quotes". Wilderness Society. Retrieved January 23, 2017.

Further reading

- Neimark, Peninah; Mott, Peter Rhoades (2011). The environmental debate a documentary history, with timeline, glossary, and appendices. Amenia, N.Y.: Grey House Pub. ISBN 978-1-78034-241-2.

- Reed, Daniel. 2009. Environmental and Renewable Energy Innovation Potential Among the States: State Rankings. Applied Research Project. Texas State University.

- Tresner, Erin. 2009. Factors Affecting States' Ranking on the 2007 Forbes List of America's Greenest States. Applied Research Project, Texas State University.

External links

- Environment at the Pew Charitable Trust