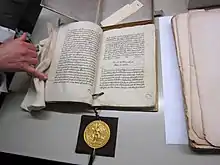

The Diet of Metz (German: Metzer Hoftag) was an Imperial Diet of the Holy Roman Empire held in the imperial city of Metz from 17 November 1356 to 7 January 1357, with Emperor Charles IV presiding. It is most memorable for the promulgation of the Golden Bull of 1356.

Background

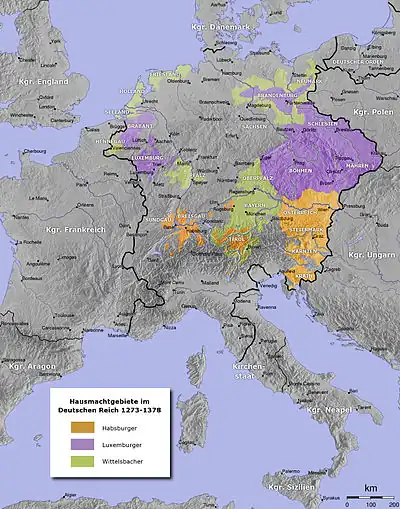

After one hundred years, the Luxembourg scion Charles IV was the first legitimate Holy Roman Emperor: while his precursor, the Wittelsbach ruler Louis the Bavarian had been crowned without the approval of the Pope, the reign of Charles IV was legitimated through his coronation by Pope Innocent VI in 1355.[1] Charles central concern was a standard regulation of the electing system of the King of Romans, inspired by the long-time struggle of his predecessor Louis with both the Roman Curia and the Habsburg anti-king Frederick the Fair.

The first part of the Golden Bull, known as the Nuremberg code of law (German Nürnberger Gesetzbuch), was composed at the Imperial Diet of Nuremberg and promulgated on 10 January 1356. During this diet the city of Metz was announced as the next meeting place for the king and the rulers.[2] Though located in the western periphery of the Empire, Charles chose the city as the venue instead of traditional gathering places like Aachen or Frankfurt. Nevertheless, Metz was one of the largest cities north of the Alps, an important trade centre, and located near the Luxembourg home territory

Process

Due to foreign affairs the beginning of the diet was postponed to the end of the year 1356. An official start date is unknown, but the adventus of the king, celebrated in Metz Cathedral on November 17, is said to be the starting point.[3] Because of the absence of several electors and the French dauphin Prince Charles V, son of King John II of France, no important decisions were made in the first three weeks. After the arrival of all electors the assembly between December 12 and December 22 concentrated on inner concerns regarding the electoral rights (German Kurrecht) of the King of Bohemia and the public peace (German: Landfrieden) in the duchies of Lorraine and Bar.

The arrival of the dauphin on December 22 marks the beginning of negotiations about the state of affair of France in the aftermath of the Battle of Poitiers in September and the completion of the last chapters of the Golden Bull.[4] The Golden Bull was promulgated by Charles on Christmas Day during a festive ceremony.[5] The resolutions were solemnly proclaimed during the Christmas celebrations. After the emperor left Metz on 7 January 1357 the assembly dissolved.

Code law

The Metz code of law (German Metzer Gesetzbuch) forms the second part of the Golden Bull with its Chapters 24 to 31. Chapter 27 and 30 were headed with a Latin text. The arrangement of chapters is a modern classification.[6] The content of the individual chapters can be summarized as follows:

- 24 (Majesty law for the electors)

- 25 (Succession of the electorate)

- 26 (Repositories of insignia and imperial insignia)

- 27 Function of the electors at festive diets (Latin De officiis principum electorum in solempnibus curiis imperatorum vel regum Romanorum)

- 28 (Seating order of the Emperor, empress and electors)

- 29 (Place of election and coronation site of the German king)

- 30 Fiefdom of the electors (Latin De iuribus officialium, dum principes feuda sua ab imperatore vel rege Romanorum recipiunt)

- 31 (Education and language teaching of the sons of the electors)[7]

Stories about the feast

It is transmitted that during the banquet of proclamation of the Golden Bull, within the area of the current place Coislin in Metz, Charles IV was served by the seven prince-electors, who carried the dishes to him on horseback. Also, during this meal, the emperor would have changed his tiara three times, successively wearing the crowns of iron, silver and gold.

According to the Metz chronicle known as "de Praillon", the centerpiece of the feast was a whole beef trojan style, roasted on a spit, in which they would have put a pig, itself stuffed with a mutton and in which they packed a goose, in whose belly was a quail, and in the quail an egg!

The opulence of this gargantuan feast is depicted in the work "splendeur et richesse de la république messine" by painter Auguste Migette (1802-1884).[8][9]

Significance

The diet of Metz was handled as a negligible factor for a long time. In more recent literature Hergemöller emphasises the political heft of the assembly.[10] Margue and Pauly point out the importance of the city of Metz for Charles reign and hint at the relevance of this diet as the first official assembly following the rules of the Golden Bull.[11]

Literature

- Gabriele Annas: Hoftag, Gemeiner Tag, Reichstag /2: Verzeichnis deutscher Reichsversammlungen des späten Mittelalters: (1349 bis 1471). Vandenhock&Ruprecht, Göttingen 2004. ISBN 3525360614

- Bernd-Ulrich Hergemöller: Der Abschluss der Goldenen Bulle zu Metz 1365/57. In: Friedrich Bernward Fahlbusch und Peter Johanek: Studia Luxemburgensia. Festschrift Heinz Stoob zum 70. Geburtstag (Studien zu den Luxemburgern und ihrer Zeit 3). Verlag Fahlbusch/Hölscher/Rieger. Warendorf 1989. S. 123-232.

- Ulrike Hohensee: Die Goldene Bulle: Politik-Wahrnehmung-Rezeption. Akademie-Verlag, Berlin, 2009. ISBN 9783050042923

References

- ↑ Peter Moraw: Karl IV. Lexikon des Mittelalters. Bd. 5. Sp.973.

- ↑ Bernd-Ulrich Hergemöller: Die Entstehung der „Goldenen Bulle“ zu Nürnberg und Metz 1355 bis 1357. In: Die Kaisermacher. Frankfurt am Main und die Goldene Bulle; 1356 - 1806; [eine Ausstellung des Instituts für Stadtgeschichte, des Historischen Museums, des Dommuseums und des Museums Judengasse (Dependance des Jüdischen Museums), Frankfurt am Main 30. September 2006 bis 14. Januar 2007]. Aufsätze, Band 2. S.31.

- ↑ Michel Margue/Michel Pauly: Luxemburg, Metz und das Reich. Die Reichsstadt im Gesichtsfeld Karls IV.. In: Ulrike Hohensee (Hg.): Die Goldene Bulle: Politik – Wahrnehmung – Rezeption. Akademie-Verlag, Berlin, 2009. S.911-912.

- ↑ Bernd-Ulrich Hergemöller: Der Abschluss der Goldenen Bulle zu Metz 1365/57. In: Friedrich Bernward Fahlbusch und Peter Johanek: Studia Luxemburgensia. Festschrift Heinz Stoob zum 70. Geburtstag. Verlag Fahlbusch/Hölscher/Rieger. Warendorf 1989. S. 150-89.

- ↑ Martin Kintzinger: Karl IV. (1346-1378). In: Bernd Schneidmüller und Stefan Weinfurter: Die deutschen Herrscher des Mittelalters. Historische Portraits von Heinrich I. bis Maximilian I. (919-1519). C.H. Beck, München, 2003. S.427.

- ↑ Wolfgang D. Fritz (Hg.): Die Goldene Bulle Kaiser Karls IV. vom Jahre 1356, Text. (Monumenta Germaniae Historica, Fontes iuris Germanici in usum scholarum separatim editi, 11), Weimar 1972. S.542.

- ↑ Bernd-Ulrich Hergemöller: Die Entstehung der „Goldenen Bulle“ zu Nürnberg und Metz 1355 bis 1357. In: Die Kaisermacher. Frankfurt am Main und die Goldene Bulle; 1356 - 1806; [eine Ausstellung des Instituts für Stadtgeschichte, des Historischen Museums, des Dommuseums und des Museums Judengasse (Dependance des Jüdischen Museums), Frankfurt am Main 30. September 2006 bis 14. Januar 2007]. Aufsätze, Band 2. S.35.; Wolfgang D. Fritz (Hg.): Die Goldene Bulle Kaiser Karls IV. vom Jahre 1356, Text. (Monumenta Germaniae Historica, Fontes iuris Germanici in usum scholarum separatim editi, 11), Weimar 1972. S.623-631.

- ↑ "Metz. Savez-vous ce qu'est la fameuse Bulle d'or ?". www.republicain-lorrain.fr (in French). Retrieved 2023-03-17.

- ↑ "Du temps de la Bulle d'Or à Metz". BLE Archives (in French). Retrieved 2023-03-17.

- ↑ Bernd-Ulrich Hergemöller: Der Abschluss der Goldenen Bulle zu Metz 1365/57. In: Friedrich Bernward Fahlbusch und Peter Johanek: Studia Luxemburgensia. Festschrift Heinz Stoob zum 70. Geburtstag. Verlag Fahlbusch/Hölscher/Rieger. Warendorf 1989. S. 151-2.

- ↑ Michel Margue/Michel Pauly: Luxemburg, Metz und das Reich. Die Reichsstadt im Gesichtsfeld Karls IV. In: Ulrike Hohensee (Hg.): Die Goldene Bulle: Politik – Wahrnehmung – Rezeption. Akademie-Verlag, Berlin, 2009. S.914-5.