J. R. R. Tolkien built a process of decline and fall in Middle-earth into both The Silmarillion and The Lord of the Rings.

The pattern is expressed in several ways, including the splintering of the light provided by the Creator, Eru Iluvatar, into progressively smaller parts; the fragmentation of languages and peoples, especially the Elves, who are split into many groups; the successive falls, starting with that of the angelic spirit Melkor, and followed by the destruction of the two Lamps of Middle-earth and then of the Two Trees of Valinor, and the cataclysmic fall of Númenor.

The whole of The Lord of the Rings shares the sense of impending destruction of Norse mythology, where even the gods will perish. The Dark Lord Sauron may be defeated, but that will entail the fading and departure of the Elves, leaving the world to Men, to industrialise and to pollute, however much Tolkien regretted the fact.

Scholars have stated that Tolkien was influenced both by the fatalism of Old English poems like Deor and by the narratives of decline in classical Greek and Roman literature, especially Plato's tale of Atlantis which Tolkien explicitly linked to Númenor. Tolkien was influenced, too, by his fellow-Inkling Owen Barfield's theory that all modern languages derived by fragmentation from an ancient language that had a unified set of meanings. From this Tolkien inferred the division of peoples. As a Christian, he also had in mind the biblical fall of man from a world created perfect; this too is mirrored in the history of Middle-earth. The decline is shown in particular in the splintering of the created light through repeated re-creations.

Background

Tolkien

J. R. R. Tolkien was an orphan, his father dying when he was three, his mother, a Roman Catholic, when he was twelve.[1] He was then brought up under the supervision of a Catholic priest, Father Francis Xavier Morgan, in industrial Birmingham. The young Tolkien observed the growing city spreading over the English countryside that he had loved.[2] He remained a devout Catholic all his life, and many Christian themes are visible in his Middle-earth writings.[3] While at Oxford, he joined the informal literary circle of the Inklings, with C. S. Lewis and Owen Barfield among others.[4]

Likely sources

The medievalist Tom Shippey suggests that the Old English poem "Deor" had a profound influence on Tolkien, and its refrain became central to his writing. Tolkien translated the poem's refrain of decline, Þæs ofereode, þisses swa mæg!, as "Time has passed since then, this too can pass".[5]

The classical scholar Giuseppe Pezzini writes that "narratives of decline" are common in the literature of ancient Greece and Rome. This is seen in Hesiod and Ovid, as the gods became more detached from the lives of mortals.[6] Pezzini sees Arda's decline from its First Age "filled with Joy and Light" down to its "Twilight" Third Age as echoing the classical theme.[6] More specifically, Plato's tale of decline in Kritias from the "decadent magnificence" of Atlantis to the humdrum life of Athens is "unambiguously and intimately" linked to Tolkien's Númenor, since Tolkien actually wrote of "Númenor-Atlantis" in his letters.[6][T 1]

Splintered light

The Tolkien scholar Verlyn Flieger has described in her book Splintered Light the progressive splintering of the first created light, down through successive catastrophes, leaving smaller and smaller splinters as the ages pass. In brief, the creator Eru Iluvatar forms the universe, Eä, with innumerable stars; these light the Earth, Arda, when it is created.[9][T 2]

Angelic beings, the Valar, live in the centre of Arda, lit by two enormous lamps, Illuin and Ormal, atop mountainous pillars of rock. The "Years of the Lamps" are abruptly brought to an end when the lamps are destroyed by the fallen Vala Melkor; the powerful fiery light spills out and destroys everything around it. The world is remade with new seas and reshaped continents, no longer symmetrical; the Valar leave Middle-earth for Valinor.[9]

The Vala Yavanna, goddess of plants, does her best to recreate the light, in the form of the Two Trees of Valinor, the silver Telperion and the gold Laurelin; they alternately brighten and dim, overlapping to create periods of "dawn" and "dusk". The light of the "Years of the Trees" is gentler than the lamps, lighting only Valinor: Middle-earth lies in darkness.[9][T 3] The Two Trees exude droplets of light which the Vala Varda (who the Elves call Elbereth) catches in vats; she uses the dew from Telperion to shape bright new silver stars to give at least some light to the Elves of Middle-earth.[9][T 4]

The splintering continues. In the First Age, Fëanor, the most skilled of all Elven-smiths, makes his finest work, the three Silmarils, forged jewels containing some of the light of the Two Trees.[10][T 5] The making of the Silmarils is timely, as Melkor returns, bringing the insatiable giant spider Ungoliant to devour the Two Trees and absorb all their light into her darkness. These contain the only remaining true light not poisoned by Ungoliant.[10][T 6]

Yavanna and Nienna manage to save the last flower of Telperion, which becomes the Moon, and the last fruit of Laurelin, which becomes the Sun. These splinters of light are formed into ships to cross the sky, steered by spirits.[10][T 7]

The Silmarils are fought over in ruinous wars, as narrated in the Quenta Silmarillion. Eventually all are lost: one ends up in the sea, one is buried in the Earth, and one is sent into the sky: by the grace of Elbereth, it is carried by Eärendil the mariner, forever sailing his ship across the heavens, appearing as the Morning and Evening Star (the planet Venus). The light is still visible, but is now inaccessible to Middle-earth.[10][T 8]

The island kingdom of Númenor has as its living symbol Nimloth, the White Tree, a seedling of another tree like Telperion, though it does not shine. The Men of Númenor become proud, cease to worship the One God, Eru Ilúvatar, and rebel against the Valar. The White Tree is cut down and burned. The Valar call on Eru Ilúvatar, who reshapes the world to be round. The island of Númenor is drowned, with most of its people,[T 9] in a fall recalling both the drowning of Atlantis, as intended by Tolkien,[T 10] and the biblical stories of the fall of man and the destruction of Sodom and Gomorrah.[11] Isildur brings one fruit of Nimloth to Middle-earth; it grows as the White Tree of Gondor.[10]

Eventually the splinters become as small as the Phial of Galadriel, which she had filled with light gathered from her fountain as it refracted the light of the Star of Eärendil. The Phial enables Frodo and Sam to defeat the giant spider Shelob, descendant of Ungoliant, on their way to Mordor to destroy the Ring. The Ring contains the power of Sauron, the remaining servant of Melkor on Middle-earth.[12]

| Age | Blue/Silver light | Golden light | Jewels |

|---|---|---|---|

| Years of the Lamps | Illuin, sky-blue lamp of Middle-earth, atop tall pillar, Helcar | Ormal, high-gold lamp of Middle-earth, atop tall pillar, Ringil | |

| ending when Melkor destroys both Lamps | |||

| Years of the Trees | Telperion, silver tree, lighting Valinor | Laurelin, golden tree, lighting Valinor | Fëanor crafts 3 Silmarils with light of the Two Trees. |

| ending when Melkor strikes the Two Trees, and Ungoliant kills them | |||

| First Age | Last flower becomes the Moon, carried in male spirit Tilion's ship. | Last fruit becomes the Sun, carried in female spirit Arien's ship. | |

| Yavanna makes Galathilion, a tree like Telperion, except that it does not shine, for the Elves' city of Tirion in Valinor. | There is war over the Silmarils. | ||

| Galathilion has many seedlings, including Celeborn on Tol Eressëa | One Silmaril is buried in the Earth, one is lost in the Sea, one sails in the Sky as Eärendil's Star. | ||

| Second Age | Celeborn has seedling Nimloth, the White Tree of Númenor. | ||

| Númenor is drowned. Isildur brings one fruit of Nimloth to Middle-earth. | |||

| Third Age | A White Tree grows in Minas Tirith while a King rules Gondor. | Galadriel collects light of Eärendil's Star reflected in her fountain mirror. | |

| The tree stands dead while Stewards rule. | A little of that light is captured in the Phial of Galadriel. | ||

| The new King Aragorn brings a White Sapling into the city. | Hobbits Frodo Baggins and Sam Gamgee use the Phial to defeat the giant spider Shelob. | ||

Thus the light begins in The Silmarillion as a unity, and in accordance with the splintering of creation is divided into more and more fragments as the myth progresses. At each stage, the fragmentation increases and the power decreases, mirroring the decline and fall of Middle-earth.[13]

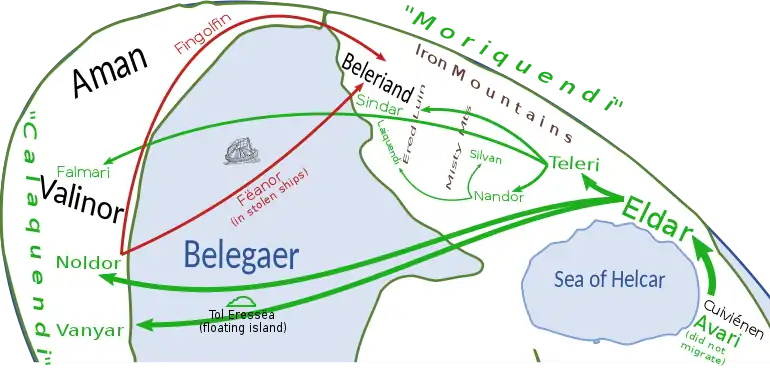

Fragmentation of languages and peoples

The Inkling Owen Barfield had a theory of language, described in his 1928 book Poetic Diction, that interested Tolkien. Indeed, according to C. S. Lewis, Barfield's theory changed Tolkien's entire outlook. The central idea, connected to Rudolf Steiner's Anthroposophy, was that there was once a unified set of meanings in an ancient language, and that modern languages are derived from this by fragmentation of meaning.[14] Tolkien took the fragmentation of language to imply the sundering of peoples, in particular the Elves. He took the division into Light and Dark Elves from Norse mythology, but went much further, devising a complex pattern of repeated splitting, migrations, and wars between kindred peoples, seen especially in the sundering of the Elves.[15]

Successive falls

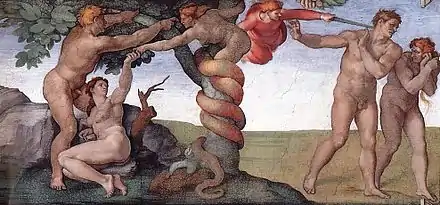

The biblical fall of man begins with a perfect created world; an angel is tempted by pride, and falls, becoming a powerful evil spirit; it in turn tempts humans, who fall; they are cast out of the paradise-garden, which they can never re-enter, and must work for their living in the ordinary world. This pattern is mirrored in Middle-earth. The creator, Eru Iluvatar, sings the first music; one of the angelic spirits, Melkor, becomes proud and falls, singing in disharmony, and ruining everything that is made.[T 2] This first fall leads to a sequence of catastrophes, including the destruction of the Lamps, then the Two Trees, then the wars over the Silmarils.[15] Tolkien noted that reflections of the biblical fall of man can be seen in the Ainulindalë, the Kinslaying at Alqualondë, and the fall of Númenor.[T 11]

This pattern represents a profound spiritual pessimism. As a Catholic, Tolkien believed both in the fall of man, and in the redemption of Christians. This redemption might or might not be available, however, to pre-Christian pagans, even if, like Aragorn, they were clearly virtuous. Tolkien shared his pessimistic outlook with Norse mythology, in which he was an expert.[16] Among those myths is Ragnarök, in which the Norse gods, the Æsir, are defeated by the giants, and the world is drowned. Shippey writes that the heroic Norse response to such a gloomy picture was defiance, a pagan Northern courage, appearing in The Lord of the Rings as a consistent good cheer, a willingness to keep going and to keep smiling, even in the face of apparent disaster.[17]

Fading of an imagined prehistory

The Tolkien scholar Marjorie Burns notes in Mythlore that the "sense of inevitable disintegration"[18] in The Lord of the Rings is borrowed from the Nordic world view which emphasises "imminent or threatening destruction".[18] She writes that in Norse mythology, this process seemed to have started during the creation: in the realm of fire, Muspell, the jötunn Surt was even then awaiting the end of the world. Burns comments that "Here is a mythology where even the gods can die, and it leaves the reader with a vivid sense of life's cycles, with an awareness that everything comes to an end, that, though [the evil] Sauron may go, the elves will fade as well."[18]

Patrice Hannon, also in Mythlore, states that:

The Lord of the Rings is a story of loss and longing, punctuated by moments of humor and terror and heroic action but on the whole a lament for a world—albeit a fictional world—that has passed even as we seem to catch a last glimpse of it flickering and fading...[19]

In Hannon's view, Tolkien meant to show that beauty and joy fail and disappear before the passage of time and the onslaught of the powers of evil; victory is possible but only temporary.[19] She gives multiple examples of elegiac moments in the book, such as that Bilbo is never again seen in Hobbiton, that Aragorn "came never again as living man" to Lothlórien, or that Boromir, carried down the Anduin in his funeral boat, "was not seen again in Minas Tirith, standing as he used to stand upon the White Tower in the morning".[19] Since he was dead, Hannon writes, this was hardly surprising; the observation is elegiac, not informational.[19] Even the last line of the final appendix, she notes, has this tone: "The dominion passed long ago, and [the Elves] dwell now beyond the circles of the world, and do not return."[19]

Hannon compares this continual emphasis on the elegiac to Tolkien's praise for the Old English poem Beowulf, on which he was an expert, in Beowulf: The Monsters and the Critics, suggesting that he was seeking to produce something of the same effect:[19]

For it is now to us itself ancient; and yet its maker was telling of things already old and weighted with regret, and he expended his art in making keen that touch upon the heart which sorrows have that are both poignant and remote. If the funeral of Beowulf moved once like the echo of an ancient dirge, far-off and hopeless, it is to us as a memory brought over the hills, an echo of an echo.[T 13]

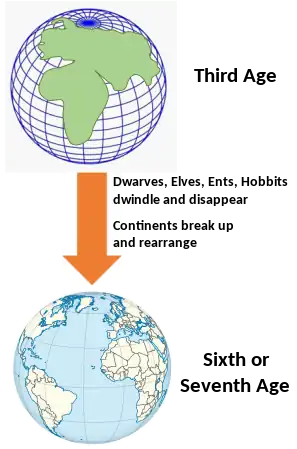

The Lord of the Rings ends with the evident dwindling or fading away of all non-human peoples in Middle-earth - the Ents have no Entwives and so are childless; the Dwarves are few and live in dispersed, isolated clusters; the monstrous Orcs and Trolls that survived the Battle of the Morannon are scattered; the last of the Elves have sailed beyond the Uttermost West to Valinor, leaving Middle-earth forever; the Hobbits are few and might easily be overlooked; the Men of Gondor have a renewal of Elvish blood, one last time, through the marriage of Arwen to their King, Aragorn.[18][19] All that is left is a world of Men, fading from past glories to the world of today, complete with the industrialisation and pollution of the planet that Tolkien so bitterly resented and regretted, as he described in "The Scouring of the Shire".[T 14]

References

Primary

- ↑ Carpenter 1981, letters #131, #151, #252

- 1 2 Tolkien 1977, "Ainulindalë"

- ↑ Tolkien 1977, ch. 1 "Of the Beginning of Days"

- ↑ Tolkien 1977, ch. 3 "Of the Coming of the Elves and the Captivity of Melkor"

- ↑ Tolkien 1977, ch. 9 "Of the Flight of the Noldor"

- ↑ Tolkien 1977,, ch. 8 "Of the Darkening of Valinor"

- ↑ Tolkien 1977,, ch. 11 "Of the Sun and Moon and the Hiding of Valinor"

- ↑ Tolkien (1977) Quenta Silmarillion

- ↑ Tolkien 1977,, "Akallabêth"

- ↑ Carpenter 1981, #131, 154, 156, 227.

- 1 2 Carpenter 1981, #131 to Milton Waldman, late 1951

- ↑ Carpenter 1981, #211 to Rhona Beare, 14 October 1958

- ↑ Tolkien 1983, pp. 5–48

- ↑ Tolkien 1955, book 6, ch. 8 "The Scouring of the Shire"

Secondary

- ↑ Carpenter 1977, pp. 24, 38.

- ↑ Carpenter 1977, pp. 34, 37, 45–51.

- ↑ Plimmer, Charlotte; Plimmer, Denis (19 April 2016). "JRR Tolkien: 'Film my books? It's easier to film The Odyssey'". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 15 December 2014.

- ↑ Carpenter 1977, pp. 152-155 and passim.

- ↑ Shippey 2005, p. 373.

- 1 2 3 Pezzini, Giuseppe (2022). "(Classical) Narratives of Decline in Tolkien: Renewal, Accommodation, Focalisation". Thersites. 15 There and Back Again: Tolkien and the Greco–Roman World (volume editors Alicia Matz and Maciej Paprocki). Article 213. doi:10.34679/THERSITES.VOL15.213.

- ↑ Garth 2020, p. 41.

- ↑ Drieshen, Clark (31 January 2020). "The Trees of the Sun and the Moon". British Library. Retrieved 24 February 2021.

- 1 2 3 4 Flieger 1983, pp. 60–63.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Flieger 1983, pp. 89–147.

- ↑ Delattre, Charles (March 2007). "Númenor et l'Atlantide: Une écriture en héritage". Revue de littérature comparée (in French). 323 (3): 303–322. doi:10.3917/rlc.323.0303. ISSN 0035-1466.

Il est évident que dans ce cadre, Númenor est une réécriture de l'Atlantide, et la lecture du Timée et du Critias de Platon n'est pas nécessaire pour suggérer cette référence au lecteur de Tolkien

- ↑ Dickerson 2006, p. 7.

- 1 2 Flieger 1983, pp. 6–61, 89–90, 144-145 and passim.

- ↑ Flieger 1983, pp. 35–41.

- 1 2 Flieger 1983, pp. 65–87.

- ↑ Ford & Reid 2011, pp. 169–182.

- ↑ Shippey 2005, pp. 175–181.

- 1 2 3 4 Burns, Marjorie J. (1989). "J.R.R. Tolkien and the Journey North". Mythlore. 15 (4): 5–9. JSTOR 26811938.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Hannon, Patrice (2004). "The Lord of the Rings as Elegy". Mythlore. 24 (2): 36–42.

- ↑ Kocher 1974, pp. 8–11.

- ↑ Lee & Solopova 2005, pp. 256–257.

Sources

- Carpenter, Humphrey, ed. (1981). The Letters of J. R. R. Tolkien. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 978-0-395-31555-2.

- Carpenter, Humphrey (1977). J. R. R. Tolkien: A Biography. New York: Ballantine Books. ISBN 978-0-04-928037-3.

- Dickerson, Matthew (2006). Ents, Elves, and Eriador: The Environmental Vision of J.R.R. Tolkien. University Press of Kentucky. ISBN 978-0-8131-7159-3.

- Flieger, Verlyn (1983). Splintered Light: Logos and Language in Tolkien's World. Wm. B. Eerdmans. ISBN 0-8028-1955-9.

- Ford, Mary Ann; Reid, Robin Anne (2011). "Into the West". In Bogstad, Janice M.; Kaveny, Philip E. (eds.). Picturing Tolkien. McFarland. ISBN 978-0-7864-8473-7.

- Garth, John (2020). The Worlds of J. R. R. Tolkien: The Places that Inspired Middle-earth. Frances Lincoln Publishers & Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-7112-4127-5.

- Kocher, Paul (1974) [1972]. Master of Middle-earth: The Achievement of J.R.R. Tolkien. Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-14-003877-4.

- Lee, Stuart D.; Solopova, Elizabeth (2005). The Keys of Middle-earth: Discovering Medieval Literature Through the Fiction of J. R. R. Tolkien. Palgrave. ISBN 978-1-40394-671-3.

- Shippey, Tom (2005) [1982]. The Road to Middle-Earth (Third ed.). HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0261102750.

- Tolkien, J. R. R. (1955). The Return of the King. The Lord of the Rings. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. OCLC 519647821.

- Tolkien, J. R. R. (1977). Christopher Tolkien (ed.). The Silmarillion. Boston: Houghton Mifflin. ISBN 978-0-395-25730-2.

- Tolkien, J. R. R. (1983). The Monsters and the Critics, and Other Essays. London: Allen & Unwin. OCLC 417591085.