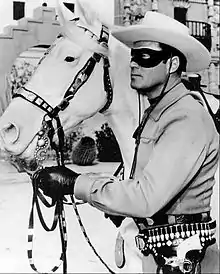

Clayton Moore | |

|---|---|

Moore as the Lone Ranger | |

| Born | Jack Carlton Moore[1] September 14, 1914 Chicago, Illinois, U.S. |

| Died | December 28, 1999 (aged 85) |

| Resting place | Forest Lawn Memorial Park in Glendale, California |

| Other names | Jack Moore Clay Moore |

| Occupation(s) | Actor, model |

| Years active | 1934–1999 |

| Known for | The Lone Ranger |

| Television | The Lone Ranger |

| Spouses |

|

| Children | 1 |

Clayton Moore (born Jack Carlton Moore, September 14, 1914 – December 28, 1999) was an American actor best known for playing the fictional western character the Lone Ranger from 1949 to 1952 and 1953 to 1957 on the television series of the same name and two related films from the same producers.

Early life

Born in Chicago, Illinois, in 1914, Moore was the youngest of three sons of Theresa Violet (née Fisher) and Charles Sprague Moore.[2][3] Moore's father, according to the federal census of 1930, was a native of New York and supported his family in Chicago by working as a real estate broker.[2] That same census also documents that a full-time maid, Amelia Hirsch, lived with the Moore family, an indication of the household's relative prosperity at the time.

Highly athletic as a boy, "Jack" became a circus acrobat by age eight, and later, in 1934, he appeared at the Century of Progress Exposition in Chicago with a trapeze act.[4] He graduated from Stephen K. Hayt Elementary School, Sullivan Junior High School, and Senn High School on the far North Side of Chicago.[5]

Career

Modeling and acting

Moore as a young man worked successfully as a John Robert Powers model. Moving to Hollywood in the late 1930s, he worked as a stuntman and bit player between modeling jobs. Moore in his 1996 autobiography I Was That Masked Man noted that Hollywood producer Edward Small persuaded him around 1940 to adopt the stage name "Clayton". Subsequently, he was cast as an occasional player in B Westerns and the lead in four Republic Studio cliffhangers and in two films for Columbia Pictures.

Military service

During World War II, Moore enlisted in the U.S. Army Air Forces and served with that branch's First Motion Picture Unit making training films, such as Target-Invisible, in which Moore co-starred with fellow actor Arthur Kennedy.

The Lone Ranger

In 1949, Moore's work in the Ghost of Zorro serial drew the attention of George W. Trendle, co-creator and producer of a popular radio series titled The Lone Ranger. The series' running plot involved the exploits of a mysterious former Texas Ranger, the sole survivor of a Ranger posse ambushed by a gang of outlaws, who roamed the West with his Indian companion Tonto to battle evil and help the downtrodden. When Trendle brought the radio program to television, Moore landed the title role. With the "March of the Swiss Soldiers" finale from Rossini's William Tell overture as their theme music, Moore and co-star Jay Silverheels made history as the stars of the first Western written specifically for television.[6] The Lone Ranger soon became the highest-rated program to that point on the fledgling ABC network and its first true hit.[7] It earned an Emmy Award nomination in 1950.

Moore was replaced in the third season by John Hart,[8] reportedly due to a contract dispute,[9] but he returned for the final two seasons. Moore later said he received no explanation from the producers as to why he was replaced or why he was rehired.[4] The fourth season of The Lone Ranger was again filmed in black and white; however, the fifth and final season of the series was the only one to be shot in color. In all, Moore starred in 169 of the 221 episodes produced.[10]

Moore appeared in other television series during his Lone Ranger run, including a 1952 episode of Bill Williams' syndicated Western The Adventures of Kit Carson. He guest-starred in two episodes of Jock Mahoney's series The Range Rider in 1952 and 1953. Silverheels and he also starred in two feature-length Lone Ranger motion pictures. After completion of the second feature, The Lone Ranger and the Lost City of Gold, in 1958, Moore began 40 years of personal appearances (including for the short-lived Lone Ranger Restaurants in Southern California[11]), TV guest spots, and classic commercials as the legendary masked man. Silverheels joined him for occasional reunions during the early 1960s. Throughout his career, Moore expressed respect and love for Silverheels.

One of Moore’s personal appearances in character became the basis of a story that actor Jay Thomas told every year around Christmas beginning in 2000 on The Late Show with David Letterman. Thomas was a radio disc jockey at the time in North Carolina and happened to be doing a show at a car dealership where Moore was appearing in character as The Lone Ranger. Moore had been stranded at the dealership, and Thomas offered him a ride back to his hotel. On the way, a passing motorist struck Thomas’ Volvo with enough force to break a headlight. Thomas gave chase and eventually cornered the man in a parking lot where he threatened to press charges. The driver of the other car taunted Thomas by saying nobody would believe his story, but Moore emerged from the back seat of the car — still wearing his costume — and said “they’ll believe me, citizen” to the stunned driver. With one exception, Thomas returned to Letterman’s show to tell the story every December until Letterman’s retirement.[12]

Lawsuit

In 1979, Jack Wrather, who owned the Lone Ranger character, obtained a court order prohibiting Moore from making future appearances as The Lone Ranger.[13] Wrather was in the process of making a new film version of the story and believed that Moore's public appearances in character would undercut the value of the character and the film, and also advance any rumors that the 65-year-old Moore would be playing the title role in the new picture (which he did not).

Wrather's move was disastrous. Moore responded by filing a countersuit and then slightly changed his costume, replacing the domino mask with a pair of Foster Grant wraparound sunglasses and participating in the company's "Who's that behind those Foster Grants?" ad campaign. The public was strongly in favor of Moore, as evidenced when moviegoers stayed away from Wrather's film. The Legend of the Lone Ranger was released in 1981, was panned by critics, and earned only $12 million at the box office, two-thirds of the film's budget. The legal proceedings between Moore and Wrather dragged on until 1984, when Wrather suddenly dropped the lawsuit permitting Moore to again make public appearances as the Lone Ranger; Wrather died of cancer two months after dropping the suit.

Moore & the Lone Ranger

Moore often was quoted as saying he had "fallen in love with the Lone Ranger character" and strove in his personal life to take The Lone Ranger Creed to heart. This, coupled with his public fight to retain the right to wear the mask, made Moore and his character inseparable. In this regard, he was much like another cowboy star, William Boyd, who portrayed the Hopalong Cassidy character. Moore was so identified with the masked man that he is the only person on the Hollywood Walk of Fame, as of 2006, to have his character's name along with his on the star, which reads, "Clayton Moore — The Lone Ranger". He was inducted into the Stuntman's Hall of Fame in 1982 and in 1990 was inducted into the Western Performers Hall of Fame at the National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum in Oklahoma City, Oklahoma. Moore also was awarded a place on the Western Walk of Fame in Old Town Newhall, California.

Later life and death

In 1964 Clayton moved to Golden Valley, Minnesota with his wife and daughter to be closer to his wife's family in Minneapolis.[14] He obtained a Minnesota real estate license, established Ranger Realty, and helped to develop the area that is now north of Interstate 394 near the Louisiana Avenue exit.[15] During that time he once came upon the scene of a crime and untied a grocery store manager shortly after the store had been robbed, apparently quipping, "You have just been rescued by the Lone Ranger."[16]

Clayton Moore died on December 28, 1999, in a West Hills, California, hospital after suffering a heart attack at his home in nearby Calabasas. He was survived by his fourth wife, Clarita Moore (née Petrone), and an adopted daughter, Dawn Angela Moore. Clayton Moore is buried at Forest Lawn Memorial Park in Glendale.[1][17][18][19]

Filmography

| Year | Title | Role | Note |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1937 | Forlorn River | Cowboy | uncredited |

| 1937 | Thunder Trail | Cowboy | uncredited |

| 1938 | Go Chase Yourself | Reporter | uncredited |

| 1939 | Burn 'Em Up O'Connor | Hospital Intern | as Jack Moore |

| 1940 | Kit Carson | Paul Terry | |

| 1940 | The Son of Monte Cristo | Lieutenant Fritz Dorner | |

| 1941 | International Lady | Sewell | |

| 1941 | Tuxedo Junction | Bill Bennett | |

| 1942 | Black Dragons | FBI Agent Richard 'Dick' Martin | |

| 1942 | Perils of Nyoka | Dr. Larry Grayson | |

| 1942 | Outlaws of Pine Ridge | Lane Hollister | |

| 1946 | The Bachelor's Daughters | Bill Cotter | |

| 1946 | The Crimson Ghost | Ashe | |

| 1947 | Jesse James Rides Again | Jesse James | |

| 1947 | Along the Oregon Trail | Gregg Thurston | |

| 1948 | G-Men Never Forget | Agent Ted O'Hara | |

| 1948 | Marshal of Amarillo | Art Crandall | |

| 1948 | Adventures of Frank and Jesse James | Jesse James | |

| 1949 | The Far Frontier | Tom Sharper | |

| 1949 | Sheriff of Wichita | Raymond D'Arcy | |

| 1949 | Riders of the Whistling Pines | Henchman Pete | |

| 1949 | Ghost of Zorro | Ken Mason/ el Zorro | |

| 1949 | Frontier Investigator | Scott Garnett | |

| 1949 | The Gay Amigo (The Cisco Kid) | Lieutenant | |

| 1949 | South of Death Valley | Brad | |

| 1949 | Masked Raiders | Matt Trevett | |

| 1949 | The Cowboy and the Indians | Henchman Luke | |

| 1949 | Bandits of El Dorado | B. F. Morgan | |

| 1949 | Sons of New Mexico | Rufe Burns | |

| 1949/1957 | The Lone Ranger | The Lone Ranger | (TV series) 169 episodes |

| 1951 | Cyclone Fury | Grat Hanlon | |

| 1951 | Kansas Pacific | Stone | |

| 1952 | Son of Geronimo: Apache Avenger | Jim Scott | as Clay Moore |

| 1952 | The Hawk of Wild River | The Hawk | |

| 1952 | Radar Men from the Moon | Graber | |

| 1952 | Night Stage to Galveston | Clyde Chambers | |

| 1952 | Captive of Billy the Kid | Paul Howard | |

| 1952 | Buffalo Bill in Tomahawk Territory | Buffalo Bill | |

| 1952 | Montana Territory | Deputy George Ives | |

| 1953 | Jungle Drums of Africa | Alan King | as Clay Moore |

| 1953 | Kansas Pacific | Henchman Stone | |

| 1953 | The Bandits of Corsica | Ricardo | |

| 1953 | Down Laredo Way | Chip Wells | |

| 1954 | Gunfighters of the Northwest | Bram Nevin | |

| 1955 | Apache Ambush | Townsman | |

| 1956 | The Lone Ranger | The Lone Ranger | (1956 film) |

| 1958 | The Lone Ranger and the Lost City of Gold | The Lone Ranger | (1958 film) |

| 1959 | Lassie | The Lone Ranger | (TV series) Guest star |

References and notes

- 1 2 "Clayton Moore, the 'Lone Ranger,' dead at 85". CNN. Retrieved October 19, 2009.

- 1 2 "Fifteenth Census of the United States: 1930", enumeration date April 9, 1930, Ward 49, Block 25, Chicago, Cook County, Illinois. Bureau of the Census, United States Department of Commerce, Washington, D.C. Digital copy of original enumeration page available at FamilySearch, a free online genealogical database provided as a public service by The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Salt Lake City, Utah. Retrieved August 1, 2017.

- ↑ The first name of Moore's mother is spelled "Thresa" in the United States Census of 1930, but her name on Clayton Moore's ("Jack Carlson Moore") Chicago birth certificate and on other documents is given as "Theresa". FamilySearch. Retrieved August 2, 2017.

- 1 2 Goldstein, Richard (December 29, 1999). "Clayton Moore, Television's Lone Ranger And a Persistent Masked Man, Dies at 85". The New York Times. Retrieved April 25, 2010.

- ↑ "Illinois Hall of Fame". Illinois State Society Of Washington, DC. Retrieved March 16, 2014.

- ↑ Billy Hathorn, "Roy Bean, Temple Houston, Bill Longley, Ranald Mackenzie, Buffalo Bill, Jr., and the Texas Rangers: Depictions of West Texans in Series Television, 1955 to 1967", West Texas Historical Review, Vol. 89 (2013), pp. 102–103

- ↑ "Jan 30, 1933: The Lone Ranger debuts on Detroit radio". History.com. Retrieved March 7, 2011.

- ↑ McLellan, Dennis (September 22, 2009). "John Hart dies at 91; the other 'Lone Ranger'". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved November 1, 2010.

- ↑ Moore, Clayton; Thompson, Frank (October 1, 1998). I Was That Masked Man. Taylor Trade Publishing. p. 130. ISBN 978-0878332168.

- ↑ McLellan, Dennis (June 12, 1993). "After 60 Years, the Lone Ranger Still Lives". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved September 27, 2010.

- ↑ Lone Ranger Restaurant

- ↑ "It's Wouldn't Be the Holidays Without Jay Thomas' Lone Ranger Story". Animalnewyork.com. Retrieved June 20, 2014.

- ↑ "Who's That Masked Man? Hi-Yo-It's Clayton Moore!". Los Angeles Times. January 15, 1985. Retrieved November 1, 2010.

- ↑ "History | Golden Valley, MN". www.goldenvalleymn.gov. Retrieved April 18, 2022.

- ↑ Tribune, Jeff Strickler Star. "TV's Lone Ranger had Minnesota ties". Star Tribune. Retrieved April 18, 2022.

- ↑ Editor, Rachel Wittrock Associate (July 11, 2013). "Hi-ho Silver, Away! Lessons learned from the Lone Ranger". Hometown News LP. Retrieved April 18, 2022.

{{cite web}}:|last=has generic name (help) - ↑ Vallance, Tom (December 30, 1999). "Obituary: Clayton Moore". The Independent. London. Archived from the original on October 2, 2009. Retrieved October 19, 2009.

- ↑ Stassel, Stephanie (December 29, 1999). "Clayton Moore, TV's 'Lone Ranger,' Dies". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved October 19, 2009.

- ↑ "Lone Ranger star dies". BBC. December 29, 1999. Retrieved October 19, 2009.

Autobiography

- I Was That Masked Man, by Clayton Moore with Frank Thompson, Taylor Publishing Company, 1996 – ISBN 0-87833-939-6

External links

- Jay Thomas talks about Clayton Moore on Letterman on YouTube

- Clayton Moore at IMDb

- Clayton Moore Memorial

- Clayton Moore at The Old Corral (b-westerns.com)

- "Clayton Moore, Television's Lone Ranger And a Persistent Masked Man, Dies at 85", by Richard Goldstein, The New York Times, December 29, 1999

- Clayton Moore at Find a Grave

- Sept 2014 interview with daughter, Dawn Moore