In chemistry, the term chicken wire is used in different contexts. Most of them relate to the similarity of the regular hexagonal (honeycomb-like) patterns found in certain chemical compounds to the mesh structure commonly seen in real chicken wire.

Examples

Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons

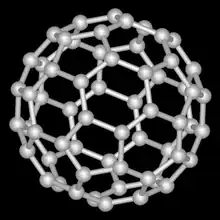

Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons or graphenes—including fullerenes, carbon nanotubes, and graphite—have a hexagonal structure that is often described as chicken wire-like.[1][2][3]

Hexagonal molecular structures

A hexagonal structure that is often described as chicken wire-like can also be found in other types of chemical compounds such as:

- Non-aromatic polycyclic hydrocarbons, e.g. steroids like cholesterol[4]

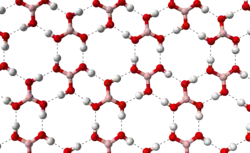

- Flat hexagonal hydrogen bonded trimesic acid (benzene-1,3,5-tricarboxylic acid),[5] boric acid, or melamine-cyanuric acid complexes[6]

- Interwoven molecule chains in the inorganic polymer NaAuS[7]

- Complexes of the protein clathrin[8]

Additional information

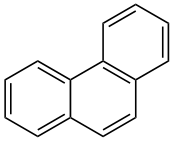

Bond line notation

The skeletal formula is a method to draw structural formulas of organic compounds where lines represent the chemical bonds and the vertices represent implicit carbon atoms.[9] This notation is sometimes jestingly called chicken wire notation.[10][11][12]

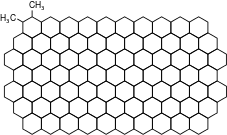

Chemical joke

It is an old joke in chemistry to draw a polycyclic hexagonal chemical structure and call this fictional compound chickenwire. By adding one or two simple chemical groups to this skeleton, the compound can then be named following the official chemical naming convention. Examples are:

- 1,2-Dimethyl-chickenwire in a cartoon by Nick D. Kim

Surface plots

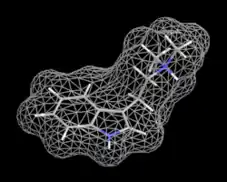

In computational chemistry a chicken wire model or chicken wire surface plot is a way to visualize molecular models by drawing the polygon mesh of their surface (defined e.g. as the van der Waals radius or a certain electron density). [13]

References

- ↑ "Soccerballs". Calpoly.edu. Retrieved 2013-11-24.

- ↑ "General Chemistry Online: Glossary". Antoine.frostburg.edu. Retrieved 2013-11-24.

- ↑ "Space Chemicals: Scientific American". Sciam.com. Retrieved 2013-11-24.

- ↑ "Get Healthy...Get Smart". Gethealthygetsmart.com. Archived from the original on 2012-07-17. Retrieved 2013-11-24.

- ↑ Suzuki, Yuto; Histaki, Ichiro (12 October 2023). "Structural details of carboxylic acid-based Hydrogen-bonded Organic Frameworks (HOFs)". Polymer Journal. 56. Retrieved December 26, 2023.

- ↑ Andrew D. Burrows (2004). "Crystal Engineering Using Multiple Hydrogen Bonds". Structure and Bonding. 108: 55–96. doi:10.1007/b14137. ISBN 978-3-540-20084-0. ISSN 0081-5993.

- ↑ Axtell Ea, 3rd; Liao, JH; Kanatzidis, MG (October 1998). "Flux Synthesis of LiAuS and NaAuS: "Chicken-Wire-Like" Layer Formation by Interweaving of (AuS)(n)(n)(-) Threads. Comparison with alpha-HgS and AAuS (A = K, Rb)". Inorg Chem. 37 (21): 5583–5587. doi:10.1021/ic980360b. PMID 11670705.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ↑ http://bio.winona.msus.edu/wilson/cell%20biology/unit3revANSWER.doc%5B%5D

- ↑ Template Archived November 30, 2004, at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ "Chem 32 Virtual Manual". Kalee.tock.com. Retrieved 2013-11-24.

- ↑ "Stereochemistry and Chirality Part I Problems". Kalee.tock.com. 1995-11-07. Retrieved 2013-11-24.

- ↑ "Chem 32 Virtual Manual". Kalee.tock.com. Retrieved 2013-11-24.

- ↑ "MolScript v2.1: Interface to external objects". Avatar.se. Archived from the original on 2013-07-22. Retrieved 2013-11-24.