| Brushtalk | |||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

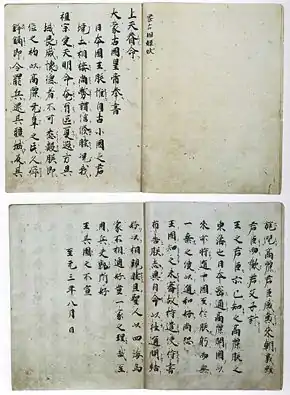

Picture of a letter in Literary Chinese from Kublai Khan to the emperor of Japan before the Mongol invasions of Japan | |||||||||||||||||||

| Chinese name | |||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 筆談 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 笔谈 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Literal meaning | to converse in brush | ||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||

| Alternative Chinese name | |||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 漢字筆談 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 汉字笔谈 | ||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||

| Second alternative Chinese name | |||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 漢文筆談 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 汉文笔谈 | ||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||

| Vietnamese name | |||||||||||||||||||

| Vietnamese alphabet | bút đàm | ||||||||||||||||||

| Chữ Hán | 筆談 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Korean name | |||||||||||||||||||

| Hangul | 필담 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Hanja | 筆談 | ||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||

| Japanese name | |||||||||||||||||||

| Kanji | 筆談 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Kana | ひつだん | ||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||

Brushtalk is a form of written communication using Literary Chinese to facilitate diplomatic and casual discussions between people of the countries in the Sinosphere, which include China, Japan, Korea, and Vietnam.[1]

History

Brushtalk (simplified Chinese: 笔谈; traditional Chinese: 筆談; pinyin: bǐtán) was first used in China as a way to engage in "silent conversations".[2] Beginning from the Sui dynasty, the scholars from China, Japan, Korea, and Vietnam could use their mastery of Classical Chinese (Chinese: 文言文; pinyin: wényánwén; Japanese: 漢文 kanbun; Korean: 한문; 漢文; hanmun; Vietnamese: Hán văn, chữ Hán: 漢文)[3] to communicate without any prior knowledge of spoken Chinese.

The earliest and initial accounts of Sino-Japanese brushtalks is dated during the Sui dynasty (581–618).[4] By an account written in 1094, minister Ono no Imoko (小野 妹子) was sent to China as an envoy. One of his goals there was to obtain Buddhist sutras to bring back to Japan. In one particular instance, Ono no Imoko had met three old monks. During their encounter, due to them not sharing a common language, held a "silent conversation" by writing Chinese characters on the ground using a stick.[4]

老僧書地曰:「念禪法師、於彼何號?」(The old monk wrote on the ground: 'Regarding the Zen Master, what title does he have there?')

妹子答曰:「我日本國、元倭國也。在東海中、相去三年行矣。今有聖德太子、无念禪法師、崇尊佛道,流通妙義。自說諸經,兼製義疏。承其令有、取昔身所持複法華經一卷、餘无異事。」(Ono no Imoko answered: 'I am from Japan, originally known as the Wa country. Situated in the middle of the Eastern Sea, it takes three years to travel here. Currently, we have the Sagely Virtue Crown Prince (Prince Shōtoku), but no Zen Master. He venerates the teachings of Buddhism, propagating profound teachings. He personally expounds upon various scriptures and creates commentaries on their meanings. Following his orders, I have come here to bring with me the single volume of the Lotus Sutra that he possessed in the past, and nothing else.')

老僧等大歡、命沙彌取之。須臾取經、納一漆篋而來、(The old monk and others were overjoyed and instructed a novice monk to retrieve it. After a moment, the scripture was brought in, placed in a lacquered box.)

The Vietnamese revolutionary Phan Bội Châu (潘佩珠) in 1905-1906 conducted several brushtalks with several other Chinese revolutionaries such as Sun Yat-sen (孫中山) and reformist Liang Qichao (梁啓超) in Japan during his Đông Du movement (東遊).[5][6] During his brushtalk with Li Qichao, it was noted that Phan Bội Châu was able to communicate with Liang Qichao using Chinese characters. They both sat at a table and exchanged sheets of paper back and forth. However when Phan Bội Châu tried reading what he wrote in his Sino-Vietnamese pronunciation, the pronunciation was unintelligible to Cantonese-speaking Liang Qichao.[5] They discussed topics mainly involving the pan-Asian anti-colonial movement.[6] These brushtalks later led to the publishing of the book, History of the Loss of Vietnam (Vietnamese: Việt Nam vong quốc sử; chữ Hán: 越南亡國史) written in Literary Chinese.

During one brushtalk between Phan Bội Châu and Inukai Tsuyoshi (犬養 毅),[7]

君等求援之事、亦有國中尊長之旨乎?若此君主之國則有皇系一人爲宜、君等曾籌及此事 (Inukai Tsuyoshi: 'Regarding the matter of seeking assistance, has there also been approval from the esteemed figures within your country? If the country is a monarchy, it would be appropriate to have a member of the imperial lineage. Have you all considered this matter?')

有之。 (Phan Bội Châu: 'Yes')

宜翼此人出境不無則落於法人之手。 (Inukai Tsuyoshi: 'It is advisable to ensure that this person leaves the country so that he does not fall into the hands of the French authorities.')

此、我等已籌及此事。 (Phan Bội Châu: 'We have already considered this matter.')

以民黨援君則可、以兵力援君則今非其辰「時」。... 君等能隱忍以待机会之日乎? (Okuma Shigenobu, Inukai Tsuyoshi, and Liang Qichao: 'Supporting you in the name of the party [of Japan] is possible, but using military force to aid you is currently not opportune. Can you gentlemen endure patiently and await the day for seizing the opportunity?')

苟能隱忍、予則何若爲秦庭之泣? (Phan Bội Châu: 'If I could endure patiently, what reason do I have not to weep for help in the Qin court?'[lower-alpha 1])

About a hundred of Phan Bội Châu's brushtalks in Japan can be found in Phan Bội Châu's book, Chronicles of Phan Sào Nam (Vietnamese: Phan Sào Nam niên biểu; chữ Hán: 潘巢南年表).[8]

There are several instances that he mentions that he used brushtalk to communicate.

以漢文之媒介也 ('used Literary Chinese as a [communication] medium')

孫出筆紙與予互談 ('Sun [Yat-sen] took out a brush and paper so we can converse')

以筆談互問答甚詳 ('using brushtalk, we engaged in serious and detailed question and answer exchanges.')

Kōno Tarō (河野 太郎) during his visit to Beijing in 2019 tweeted his schedule, but only using Chinese characters (no kana) as a way of connecting with Chinese followers. While the text is not like Chinese nor is it like Japanese, it was fairly understandable by Chinese speakers. It is a good example of Pseudo-Chinese (偽中国語) and how the two countries can somewhat communicate with each other with writing. The tweet resembled how brushtalks were used in the past.[9]

八月二十二日日程。同行記者朝食懇談会、故宮博物院Digital故宮見学、故宮景福宮参観、李克強総理表敬、中国外交有識者昼食懇談会、荷造、帰国。(Daily schedule of 22 August. Breakfast meeting with accompanying reporters, visit to the Forbidden City’s Digital Palace, visit to the Forbidden City’s Jingfu Palace, courtesy visit with Premier Li Keqiang, lunch meeting with experts on Chinese diplomacy, packing, and returning home.)

Examples

One famous example of brushtalk is a conversation between a Vietnamese envoy (Phùng Khắc Khoan 馮克寬) and a Korean envoy (Yi Su-gwang 이수광; 李睟光) meeting in Beijing to wish prosperity for the Wanli Emperor (1597).[10][11][12] The envoys exchanged dialogue and poems between each other. These poems followed traditional metrics which was made up of eight 7-syllable lines (七言律詩). It is noted by Yi Su-gwang that out of the 23 people in Phùng Khắc Khoan's delagation, only one person knew spoken Chinese meaning that the rest had to use brushtalks to communicate.[13]

Two Poems in Presentation to the Envoys of Annam (贈安南國使臣二首) – Korean question

These poems were complied in Yi Su-gwang's book, Jibongjip (지봉집; 芝峯集).

贈安南國使臣其一 A Presentation to the Envoys of Annam, Part One

|

|

|

Vietnamese transcription:

|

English translation:

|

贈安南國使臣其二 A Presentation to the Envoys of Annam, Part Two

|

|

|

Vietnamese transcription:

|

English translation:

|

Reply to the Envoy of Joseon, Yi Su-gwang (答朝鮮國使李睟光) - Vietnamese response

These poems were complied in Phùng Khắc Khoan's book, Mai Lĩnh sứ hoa thi tập (梅嶺使華詩集).

答朝鮮國使李睟光其一 Reply to the Envoy of Joseon, Yi Su-gwang, Part One

|

Vietnamese transcription:

|

|

|

English translation:

|

答朝鮮國使李睟光其二 Reply to the Envoy of Joseon, Yi Su-gwang, Part Two

|

Vietnamese transcription:

|

|

|

English translation:

|

Another encounter with Korean envoy (I Sangbong; Korean: 이상봉; Hanja: 李商鳳) and Vietnamese envoy (Lê Quý Đôn; chữ Hán: 黎貴惇) on 30 December 1760, led to a brushtalk about the dress customs of Đại Việt (大越), it was recorded in the third volume of the book, Bugwollok (북원록; 北轅錄),[14]

(黎貴惇) 副使曰:「本國有國自前明時、今王殿下黎氏、土風民俗、誠如來諭。敢問貴國王尊姓?」 (The vice envoy said: 'Our country has had its governance since the Ming Dynasty. Now, under the reign of His Royal Highness, the Lê family's local customs and traditions are indeed as mentioned. May I respectfully inquire about the surname of your esteemed royal highness?')

李商鳳曰:「本國王姓李氏。貴國於儒、佛何所尊尚?」 (I Sangbong said: 'In our country, the king's surname is I (李). In your esteemed country, what is revered and esteemed between Confucianism and Buddhism?')

黎貴惇曰:「本國並尊三教、第儒教萬古同推、綱常禮樂、有不容捨、此以為治。想大國崇尚亦共此一心也。」 (Lê Quý Đôn said: 'In our country, we equally respect the three teachings, but Confucianism, with its eternal principles, rites, and music, is universally upheld. These are considered essential for governance. I believe that even in great countries, the pursuit of such values is shared with the same sincerity.')

李商鳳曰:「果然貴國禮樂文物、不讓中華一頭、俺亦慣聞。今覩盛儀衣冠之制、彷彿我東、而被髮漆齒亦有所拠、幸乞明教。」 (I Sangbong said: 'Indeed, the cultural artifacts of your esteemed country, especially in rituals, music, and literature, are no less impressive than those of China. I have heard about it before. Today, seeing the splendid ceremonial attire and the regulations for attire and headgear, it seems reminiscent of our Eastern customs. Even the hairstyles and the lacquered teeth has its own basis. Fortunately, I can inquire and learn more. Please enlighten me.')

I Sangbong was fascinated with the Vietnamese custom of teeth blackening after seeing the Vietnamese envoys with blackened teeth.[14]

A passage in the book, Jowanbyeokjeon (Korean: 조완벽전; Hanja: 趙完璧傳), also mentions these customs,[15]

其國男女皆被髮赤脚。無鞋履。雖官貴者亦然。長者則漆齒。 (In that country, both men and women all tie up their hair and go barefoot, without shoes or sandals. Even officials and nobility are the same. As for the respected individuals, they blacken their teeth.)

The author Jo Wanbyeok (Korean: 조완벽; Hanja: 趙完璧) was sold to the Japanese by the Korean military, but since he was excellent in reading Chinese characters, the Japanese traders brought him along. From there, he was able to visit Vietnam and was treated as an guest by Vietnamese officials. His biography, Jowanbyeokjeon records his experiences and brushtalks with the Vietnamese.

See also

Notes

- ↑ "Weeping for help in the Qin court" was referring to a moment in Zuo Zhuan, where Shen Baoxu (申包胥) cried at the Qin court for seven days without eating. Duke Ai of Qin (秦哀公) moved by his actions sent troops to restore the Chu State (立依於庭牆而哭,日夜不絕聲,勺飲不入口,七日,秦哀公為之賦無衣,九頓首而坐,秦師乃出。)

- ↑ Việt Thường 越裳 refers to an ancient nation mentioned by Book of the Later Han, the location of Việt Thường is said to be in Northern Vietnam according to the Vietnamese history book, Đại Việt sử lược 大越史略.

- ↑ Cửu Chân 九真 refers to an ancient Vietnamese province while Vietnam was under Chinese rule. It is now present-day Thanh Hóa Province.

- ↑ Yanzhou 炎州 refers to a distant place in the South.

- ↑ Uian 義安 first referred to an island under the control of the Ryukyu Kingdom, but later fell to the control of Joseon Kingdom. In this context, it refers to Korea.

References

- ↑ Li, David Chor-Shing; Aoyama, Reijiro; Wong, Tak-sum (6 February 2020). "Silent conversation through Brushtalk (筆談): The use of Sinitic as a scripta franca in early modern East Asia". De Gruyter: 1.

- ↑ Li, David Chor-Shing (17 February 2021). "Writing-Mediated Interaction Face-to-Face: Sinitic Brushtalk (漢文筆談) as an Age-Old Lingua-Cultural Practice in Premodern East Asian Cross-Border Communication". Brill Publishers: 1.

- ↑ Li, David Chor-Shing (17 February 2021). "Writing-Mediated Interaction Face-to-Face: Sinitic Brushtalk (漢文筆談) as an Age-Old Lingua-Cultural Practice in Premodern East Asian Cross-Border Communication". Brill Publishers: 3.

- 1 2 Li, David Chor-Shing (17 February 2021). "Writing-Mediated Interaction Face-to-Face: Sinitic Brushtalk (漢文筆談) as an Age-Old Lingua-Cultural Practice in Premodern East Asian Cross-Border Communication". Brill Publishers: 8.

- 1 2 Li, David Chor-Shing; Aoyama, Reijiro; Wong, Tak-sum (6 February 2020). "Silent conversation through Brushtalk (筆談): The use of Sinitic as a scripta franca in early modern East Asia". De Gruyter: 4.

- 1 2 Li, David Chor-Shing; Aoyama, Reijiro; Wong, Tak-sum (2022). Brush Conversation in the Sinographic Cosmopolis Interactional Cross-border Communication using Literary Sinitic in Early Modern East Asia. Routledge. pp. 295–298. ISBN 9780367499402.

- ↑ Nguyễn, Hoàng Thân; Nguyễn, Tuấn Cường (17 Feb 2021). "Sinitic Brushtalk in Vietnam's Anti-Colonial Struggle against France: Phan Bội Châu's Silent Conversations with Influential Chinese and Japanese Leaders in the 1900s". Brill Publishers: 281.

- ↑ Nguyễn, Hoàng Thân; Nguyễn, Tuấn Cường (17 Feb 2021). "Sinitic Brushtalk in Vietnam's Anti-Colonial Struggle against France: Phan Bội Châu's Silent Conversations with Influential Chinese and Japanese Leaders in the 1900s". Brill Publishers: 276.

- ↑ Aoyama, Reijiro (17 February 2021). "Writing-Mediated Interaction Face-to-Face: Sinitic Brushtalk in the Japanese Missions' Transnational Encounters with Foreigners During the Mid-Nineteenth Century". Brill Publishers: 238–239.

- ↑ Li, David Chor-Shing; Aoyama, Reijiro; Wong, Tak-sum (6 February 2020). "Silent conversation through Brushtalk (筆談): The use of Sinitic as a scripta franca in early modern East Asia". De Gruyter: 14–15.

- ↑ 陈, 俐; 李, 姝雯. "朝鮮、安南使臣詩歌贈酬考述 — 兼論詩歌贈酬的學術意義". Korea Open Access Journals.

- ↑ Aoyama, Reijiro (17 February 2021). "Writing-Mediated Interaction Face-to-Face: Sinitic Brushtalk in the Japanese Missions' Transnational Encounters with Foreigners During the Mid-Nineteenth Century". Brill Publishers: 236.

- ↑ Nguyễn, Dị Cổ (11 December 2022). "Người Quảng xưa "nói chuyện" với người nước ngoài". Báo Quảng Nam (in Vietnamese).

- 1 2 沈, 玉慧 (December 2012). "乾隆二十五~二十六年朝鮮使節與安南、南掌、琉球三國人員於北京之交流 (Joseon Envoys' Intercourse with Annam, Lan Xang, and Ryukyu in Beijing during 1760-1761 )". 臺大歷史學報 (50).

- ↑ 李, 睟光. 趙完璧傳 (조완벽전).