| British Cemetery, Lisbon | |

|---|---|

Entrance to the British Cemetery on Rua de São Jorge. | |

| Details | |

| Established | c. 1721 |

| Location | |

| Country | Portugal |

| Coordinates | 38°42′57″N 09°09′36″W / 38.71583°N 9.16000°W |

| Owned by | British Government |

| Size | 2 hectares (4.9 acres) |

| Website | https://www.britishcemeterylisbon.com/ |

The British Cemetery (Cemitério dos Ingleses) in the Portuguese capital of Lisbon was established in the early 18th century. It is located in the Estrela district of the city and surrounds the Anglican St George's Church. The first marked grave is dated 1724. The Cemetery contains graves of early British Protestant residents and long-established British families in Portugal as well as British visitors to Lisbon. There are also 31 Commonwealth War Graves. In addition, some British Catholics and non-British Protestants, particularly Dutch, are also buried there. There is a small Jewish cemetery in an adjacent plot. Amongst the famous English people buried in the Cemetery is the novelist Henry Fielding.[1]

History

Early days

Ever since the Reformation, British Protestants living in Lisbon had felt the need for their own burial ground. The Protestant British were regarded as heretics by the Catholic Portuguese and their graves, if visible, would have been desecrated. Before the Cemetery was established the practice was to bury British dead in wooden boxes, often those previously used for the importation of sugar, in beaches at low tide, on the south bank of the River Tagus or, perhaps, in unconsecrated land in remote areas. In 1654, with Portugal in the process of regaining its independence from Spain, a treaty was negotiated between the victor of the English Civil War, Oliver Cromwell, and King João IV. British merchants campaigned with their government for land to bury their dead to be conceded under this treaty. As a result, the British undertook to respect the religion of Portugal and the British in the Lisbon area were permitted to have a plot of land for burials.[1][2][3]

As a result of opposition from the Jesuits and the Portuguese Inquisition, nothing happened to establish a cemetery until 1717, when the British Consul, W. Poyntz, was able to report to London that he had obtained a perpetual lease on suitable land under the system of Emphyteusis. The merchants who constituted the so-called British Factory had come to play a vital role in the Portuguese economy and then felt able to insist that the treaty be implemented. The Dutch in Lisbon acquired an adjacent plot in 1723 and the two nationalities joined to expand the area between 1729 and 1734. The first gravestone is that of Francis La Roche, from February 1724, although British Factory records suggest a burial in 1721, without specifying where it took place. It appears that the Dutch and British burial grounds were treated as one cemetery. There is no evidence today that the Dutch were buried in one area and the British in another.[2][3][4]

At the time it was established, the Cemetery was well outside the built-up area of the city, being surrounded by farms and vineyards. A wall was built around it, with an entrance to the west. Trees, mainly cypress, were planted, as the Inquisition wanted to "hide the graves of the heretics from the eyes of the faithful", and the plot became known as the "Cemetery of the Cypresses". The path from the entrance to St George's Church to the northwest of the plot was also bordered by cypresses. Many were blown down by a cyclone in 1941 but some of the original trees remain. Although now surrounded by roads and buildings, the Cemetery remains well wooded, but insufficiently wooded for residents of surrounding apartments who reportedly complained about the view in 2022.[5] The original British lease document was lost in the 1755 Lisbon earthquake but the first Dutch lease survives. The Cemetery, itself, was largely undamaged by the earthquake, although there is evidence of the ground levels being raised in places. According to available records, 68 British people were killed by the quake, although there is no reference to the event in Church records or on any tombstones.[1][4][6]

From its inception until 1825, the Cemetery and other charitable activities among the British of Lisbon were funded by levies on imports into Portugal by British merchants, made possible by the British Contribution Act of 1721. After 1825, the Cemetery was funded by donations, subscriptions and burial fees. In 1779-80 there was a dispute between the British and the Dutch. The British wanted to create a separate entrance on the eastern side of the Cemetery but the Dutch consul, Daniel Gildemeester (1714-1793), had erected a large tomb to his son Jan who died at the age of 22 in 1778. This tomb obstructed the planned new entrance but he refused to move it. Harmonious relations were clearly eventually restored as Gildemeester and the Dutch financed half the cost of the Cemetery's mortuary chapel, which was completed in 1794. The inscription over the door of the chapel refers to the collaboration between the British and Dutch for this purpose.[1][2][3]

Jewish graves

In 1497, King Manuel I had issued an edict requiring Jews to either convert to Christianity or leave the country, leading to a widespread exodus of Sephardi Jews. Towards the end of the 18th century some Sephardis began to return, particularly those living in London and Gibraltar, as a result of the treaty between Britain and Portugal. Because many members of this new community were British subjects, a corner of the British Cemetery was allocated for their use in 1801. However, when a request was made in 1815 to erect a Jewish tombstone, the Society of Merchants and Factors, which had replaced the British Factory, decided that, from that time, only Christian tombs would be permitted. The Jewish community responded by leasing a small adjacent plot for their burials. For some sixty years this was Lisbon's only Jewish cemetery. The last burial at the cemetery, which contains around 150 tombstones in Hebrew, took place in 1865. By this time no more space remained, and a new Jewish Cemetery was established in 1868.[3][7]

Enlargement

As a consequence of the Peninsular War, many British troops passed through Lisbon and there were two British military hospitals. The inevitable deaths meant that the Cemetery rapidly became full and it refused to accept any more military burials. In 1810, therefore, the British Government purchased an area of adjacent land somewhat larger than the existing Cemetery for the purpose of military burials. The resident British built a wall between the two plots but this was removed in 1819 when the entire site passed into control of the Society of Merchants and Factors. A line of stones to indicate the boundary between the British cemetery and the military cemetery remains. At the same time, the Dutch relinquished their interest. The area of the Cemetery then remained unchanged until 1950. In 1814 the owner of the building in Lisbon that had been used for Anglican services asked for it to be returned and, in 1819, it was decided to erect a chapel within the Cemetery. The first chapel of St. George the Martyr was dedicated in 1822. In 1886 the building was destroyed by fire. With active fundraising by the chaplain, Canon Thomas Godfrey Pembroke Pope, the present church, designed by architects in London, was consecrated in 1889.[2][3][4]

Loss of land

In 1940 it was decided to build a new road along the southern boundary of the Cemetery. Lisbon Council and the national government, represented by Duarte Pacheco, an engineer who had been appointed Minister of Public Works and Transport at the young age of 33, did not want to take much land from the Estrela Gardens to the south of the Cemetery so they planned to compulsorily purchase both corners of the southern zone of the Cemetery, which projected into the proposed route of the road. Initial efforts by the British to have the plans changed were unsuccessful, despite the involvement of the British Ambassador, Sir Walford Selby. British proposals for an alternative route were dismissed on the grounds that it would mean cutting down trees in the Estrela Gardens and would affect the symmetry of the original plan. The Government argued that this could not be justified in order to preserve just 800 square meters of the 20,000 square meters (2 hectares) of the Cemetery. The new British Ambassador, Sir Ronald Hugh Campbell, who had a higher status than his predecessor, also became involved, writing to the Portuguese prime minister, António de Oliveira Salazar, but to no avail.[2][4][8]

In mid-1942, the Cemetery's trustees, realising that they were fighting a losing battle, agreed to the transfer of the land, suggesting a price for the land. The municipality replied verbally with an offer of 5% of the British figure, having already agreed to carry out the movement of buildings and graves and wall reconstruction free of charge. The Government's plan required the movement of at least 37 graves, which included seven graves of Jews who had arrived in Lisbon from Gibraltar. The original entrance would have had to be relocated and the mortuary chapel moved to another location. In 1943 Pacheco died in a car crash near the town of Vendas Novas. In 1944 the Cemetery land was registered as belonging to the British Government and remains so, although the United Kingdom does not contribute to its upkeep. Authorised by the government in London, this registration was seen as a way of protecting the entire area from expropriation. However, in the face of growing public hostility, this move achieved little and the matter was finally resolved in the courts on 25 May 1950. The money received in compensation for the Cemetery land given up was used to buy the freehold of some surrounding land. The mortuary chapel was moved to its present position, brick by brick. A new caretaker's house was constructed at the same time. The new road was named Rua de São Jorge (St George's Rd) and the present entrance to the Cemetery was constructed on that road, preserving the stone plaque that had been over the original entrance. Since these works were completed there have been few changes to the Cemetery.[1][2][4][8]

The long-term future of the Cemetery remains uncertain. Five acres of land surrounding it, including the former British Hospital, were sold by the British Government in 2018 for construction of apartments. A new section of the Lisbon Metro was scheduled to pass close by.[5] There is also concern about the long-term impact on the cemetery of climate change and, as of 2023, efforts were underway to identify more suitable plants.[9]

Burials, graves and monuments

The graves and monuments include good examples of Georgian, Regency, and Victorian architecture, as well as modern monuments:

- African slaves. Although there are no marked graves, the records indicated that several of the British merchants had slaves, that they were baptised and that some were buried in the Cemetery.[2]

- Boer Memorial. During the 1899-1902 Second Boer War, many Boers retreated into the Portuguese colony of Mozambique. They were later interned in Portugal and 14 died there. Only one is buried in the Cemetery, Johannes Christoffel Nel, but an imposing pink monumental cross was erected in 1913 to commemorate all who died in Portugal, with inscriptions in both English and Dutch. Nel is buried beneath the monument.[1]

- Carl Ludwig Christian Rümker was a German astronomer. His grave is an example of the practice of illustrating the work or hobbies of the deceased.[4][10]

- Christian August, Prince of Waldeck and Pyrmont (1744-1798). Waldeck was a Prussian soldier and prince, whose skill in advising the Portuguese army led the Portuguese crown to erect a large marble pyramid in his honour.[2]

- Daniel Gildemeester built the tomb for his son that led to conflict between the British and the Dutch. He is buried in the same tomb. Gildemeester was an affluent Dutch consul who built the Seteais Palace in Sintra.[2]

- David de Pury was a Swiss banker who moved to Lisbon in 1736, founding a bank. Much honoured and admired in his life, he was a major benefactor of the Swiss city of Neuchâtel. However, more recently his contributions have been reconsidered because of his role in the slave trade.[11]

- Ernest Urdărianu was the Minister of the Court during the reign of King Carol II of Romania (1930–1940). As closest confidant of the King, Urdăreanu was, alongside Madame Lupescu, the King's mistress, the third member of the triumvirate that held power in the Romania during the 1930s.[12]

- Francis La Roche was the first recorded burial. Like many other members of the British Factory, he was a Huguenot Protestant refugee who left France to escape repression by the Catholics. He became a successful businessman.[1][2]

- Garland family graves. The Garlands were traders in bacalhau or salted cod from Newfoundland. Thomas Garland, was sent to Lisbon in 1776 to set up an agency to handle shipping arrangements, which also involved exporting salt from Setúbal for use in the bacalhau trade.[4][13]

- Henry Fielding. The English dramatist and satirical novelist, Henry Fielding (1707-1754), died on 8 October 1754. This was just two months after arriving in Portugal on a trip to improve his health as he was suffering from tuberculosis, gout, asthma, and cirrhosis of the liver. No one knows exactly where he was buried, as burial records for the period 1754-1762 are missing, but a monument to him in the form of a raised tomb was erected by public subscription in 1830.[1]

- Jerónimo Osório de Castro Cabral e Albuquerque was a general in the Portuguese army who married an English woman and became a Protestant. His grave also provides an example of the deceased's career being illustrated, with an effigy of his helmet and sword.[14]

- John Stott Howorth owned the Sacavém Ceramics Factory, to the north of Lisbon. Friends with the Portuguese royal family, he was made Baron Howorth of Sacavém.[4][15]

- John Jeffery was an English politician who was a member of parliament for Poole. He later became British Consul in Lisbon, where he died in 1822. He has an imposing tomb.[2]

- John Bristow was an English businessman who lost a lot of money as a result of the 1755 Lisbon earthquake and was in Portugal to collect debts when he died.[16]

- Miklós Horthy, also known as Nicholas, had been the Regent of Hungary between 1920 and 1944. During World War II Hungary was effectively on the side of the Nazis and he was taken to Nuremberg for the Nuremberg trials of war criminals. He was never charged and came to believe he had been arrested by the Allies to protect him from the Soviet Union. He gave evidence at those trials and eventually settled in Estoril, Portugal, where he died in 1957. He was buried in the Cemetery but his body was relocated to the family crypt in Kenderes, Hungary in 1993.[2][17]

- Patrick Ramsay was a British ambassador to several countries, who settled in Estoril on his retirement in 1939 and worked during World War II as a volunteer at the British Embassy in Lisbon.[2]

- Philip Doddridge was a Nonconformist minister and writer of hymns who went to Portugal for his health but succumbed to his illness in 1751. A second tombstone was added to his grave in 1828.[2]

- Paulo Lowndes Marques (1941-2011) was a founder member of the CDS – People's Party and Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs in Portugal. With a Portuguese father and a British mother, he was an active promoter of Anglo-Portuguese relations.[18]

- Rankin family graves. The Rankins were cork importers and cork product manufacturers in Scotland. Having made regular visits to Portugal, the family decided it would be useful to establish a permanent presence and William Rankin moved to Portugal in 1872. The family has been in the country since then and several members are buried in the Cemetery.[4][19]

- Rawes family graves. James Rawes went to Portugal in 1827, trading in Porto as a cloth merchant. The family moved to Lisbon, becoming shipping and insurance agents and there are still family members in the city.[4]

- Stephens family graves. The first member of the family in Portugal, John Stephens, was involved with lime kilns in Lisbon. His nephew, William Stephens, rescued and developed the glass factory at Marinha Grande, initially supplying glass that was much-needed after the 1755 earthquake. His younger brother, John James, continued the business, eventually bequeathing the factory to the Portuguese nation. His monument, and that of another brother, Lewis, are in the Cemetery, and other relatives are also buried there.[2]

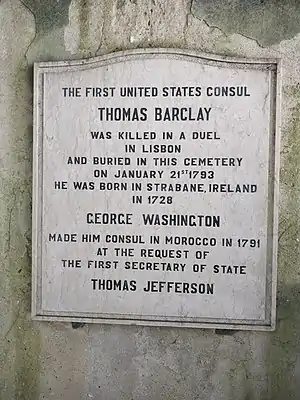

- Thomas Barclay, originally Irish, was the first American ambassador in Morocco. A memorial tablet on the Cemetery wall states that he was killed in a duel, although this is disputed.

- Thomas Parr is recorded by a monument inside the mortuary chapel. He was a member of the British Factory and a noted benefactor of Christ's Hospital school in England, which agreed to part-finance the mortuary chapel subject to the monument to Parr being included.[2]

- Thomas Godfrey Pembroke Pope, former chaplain of St George's Church, his wife Louisa Ann, half sister to Robert Baden-Powell, founder of the Scouting movement, and their son William Godfrey Thomas Pope, the former general manager of the Anglo-Portuguese Telephone Company.

Military graves

18th and 19th centuries

Many of those buried were poor soldiers and sailors, particularly of English but also Dutch origin, for whom there is no plaque or tombstone and, who, in many cases were not even recorded in the records, particularly between 1761 and 1763 at the end of the Seven Years' War, when British forces were in Lisbon. The Chaplain was ill at this time and did not keep records. There are only two marked graves from the Peninsular War period, those of Captain Francis Livingstone and Lieutenant-Colonel William Offeney. In December 1811, Portuguese soldiers, acting under orders from General Beresford, who had been appointed Commander-in-Chief of the Portuguese Army, forced open the door of the Cemetery in order to inter the remains of Brigadier General Francis John Coleman. It is believed that many other British soldiers were buried there during this period but there are no other marked graves. In 1827 a British force commanded by Sir Robert Clinton landed in Lisbon in support of Queen Maria II in the Civil War against Dom Miguel. The British left the following year but cemetery records record the burial of 90 people while it was in Lisbon.[6]

Commonwealth War Graves

Although Portugal was neutral in World War II, many members of the British armed forces lost their lives in Portugal or its waters. Airmen heading to Gibraltar from Cornwall died when their planes crashed, while British ships were torpedoed in Portuguese waters. The Commonwealth War Graves Commission maintains 26 World War II graves of members of the British Navy, Air Force and Army, as well those of the Royal Canadian Air Force, the Merchant Navy, and the British Overseas Airways Corporation. Three members of the crew of the SS Avila Star, torpedoed off the Azores, are buried in the cemetery. There are also five burials from World War I. The headstones follow the same style as in other cemeteries supported by the commission.[2][20]

Archives

The first detailed survey of the inscriptions on the memorials in the cemetery was carried out in 1824. This was invaluable as it provided the only full transcript of memorials where the lettering can no longer be read. A second survey was completed in 1943 by the then Chaplain, Henry Frank Fulford Williams. A new survey was completed in 2023.[9]

Visits

The Cemetery entrance is in Rua de São Jorge, Lisbon. It is open from 10.30 to 13.00 on every day except Saturdays. An informative leaflet, with a map, can be purchased. The Jewish graves cannot be visited.

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Pead, John. "History of the British Cemetery". British Cemetery. Retrieved 19 July 2021.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 Harmar, L. C. D'O. (1977). "St. George's Cemetery, Lisbon". British Historical Society of Portugal Annual Report. 4: 15. Retrieved 23 July 2021.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Howes, Robert (2004). The British Cemetery in Lisbon. Lisbon: British Historical Society of Portugal (Crown Copyright).

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Visitor Guide: The British Cemetery - Lisbon. Lisbon Anglicans.

- 1 2 Wilkinson, Isambard. "Developers put British cemetery in Lisbon under siege". The Times. Retrieved 22 March 2022.

- 1 2 "The cemetery". Lisbon Anglicans. Retrieved 18 July 2021.

- ↑ Marshall, Oliver. "Lisbon's hidden Jewish cemetery". The World Elsewhere. Retrieved 19 July 2021.

- 1 2 Humphreys, John (1991). "A Little Patch of Ground The ten-year battle to preserve the original boundaries of the British Cemetery in Lisbon". British Historical Society of Portugal Annual Report. 18: 105. Retrieved 20 July 2021.

- 1 2 Godfrey, Edward. "Report on the presentation at St. George's Church, Lisbon of the new Inscriptions Survey of the British Cemetery memorials" (PDF). British Historical Society of Portugal. Retrieved 28 October 2023.

- ↑ "Interesting monuments". The British Cemetery Lisbon. Retrieved 10 January 2022.

- ↑ "Switzerland joins debate about removing controversial memorials". SWI swissinfo.ch.

- ↑ Moats, Alice-Leone (1955). Lupescu. The story of a royal love affair. New York: Henry Holt and Company.

- ↑ "The Garland Family". British Historical Society of Portugal. Retrieved 24 July 2021.

- ↑ Howe, Malcolm (2016). "Monumental heraldry in St. George's Anglican Church and the British Cemetery, Estrela, Lisbon". British Historical Society of Portugal Annual Report. 43: 17. Retrieved 24 July 2021.

- ↑ Sacavém, pottery like no other. Loures, Portugal: Loures Municipal Council. November 2019. p. 176. ISBN 978-972-9142-58-1.

- ↑ Booker, Peter (2016). "John Bristow (1707 - 1768) and the Lisbon Earthquake". British Historical Society of Portugal Annual Report. 43. Retrieved 26 January 2022.

- ↑ Horthy, Nicholas; Simon, Andrew L. (2000). Admiral Nicholas Horthy: MEMOIRS (PDF). Florida: Simon Publications. ISBN 978-4871879132.

- ↑ "Paulo Portas recorda Paulo Lowndes Marques". SAPO Journais. Retrieved 3 August 2021.

- ↑ Rankin, Carol (2002). "An Account of the Rankin Family in Portugal". British Historical Society of Portugal Annual Report. 29: 50. Retrieved 23 July 2021.

- ↑ "Lisbon (St George) British Churchyard". Commonwealth War Graves Commission. Retrieved 25 July 2021.