| Battle of Forum Gallorum | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the War of Mutina | |||||||

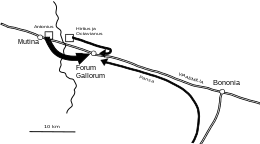

.jpg.webp) A map of Cisalpine Gaul at the time of the battle, showing the locations of Forum Gallorum and Mutina on the Via Aemilia | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Roman Senate | Mark Antony's forces | ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

Gaius Pansa (DOW) Aulus Hirtius Octavian |

Mark Antony Marcus Junius Silanus | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

Pansa:

Hirtius:

|

Antony:

| ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

Pansa: heavy Hirtius: light | About half the force | ||||||

The Battle of Forum Gallorum was fought on 14 April 43 BC between the forces of Mark Antony and legions loyal to the Roman Senate under the overall command of consul Gaius Pansa, aided by his fellow consul Aulus Hirtius. The untested Caesar Octavian (the future emperor Augustus) guarded the Senate's camp. The battle occurred on the Via Aemilia near a village in northern Italy, perhaps near modern-day Castelfranco Emilia.

Antony was attempting to capture the province of Cisalpine Gaul from its appointed governor, Decimus Brutus. Brutus was besieged by Antony in Mutina (modern Modena), just south of the Padus (Po) River on the Via Aemilia. The Roman Senate sent all its available forces to confront Antony and relieve Brutus. Hirtius and Octavian arrived near Mutina with five veteran legions, where they waited for Pansa, who was marching north from Rome with a further four legions of recruits. Antony had four veteran legions in addition to the troops that were besieging Mutina. Aware that he would soon be outnumbered, Antony sought to defeat his opponents in detail before they could link up. After failing to provoke a battle with Hirtius, Antony marched two of his legions between the two Senatorial armies and laid an ambush on Pansa's approaching recruits. Unknown to Antony, Pansa had already been joined by one of Hirtius' veteran legions and Octavian's praetorian cohorts.

Antony's forces caught Pansa's army by surprise on a narrow road surrounded by marshes. A bitter, bloody battle ensued, in which Antony's II and XXXV legions defeated Pansa's troops and forced them to retreat southwards. Pansa himself was severely wounded. Antony called off the pursuit of Pansa's broken army and began marching his jubilant troops back towards Mutina. Hirtius then arrived from the north with a single veteran legion, which crashed into Anthony's exhausted troops, taking two Roman eagles and 60 standards. Antony's victory was turned into a major defeat; he fell back with his cavalry to his camp outside Mutina.

After receiving a report of the battle, Marcus Tullius Cicero, a fierce adversary of the Antonian faction, pronounced in the Senate the Fourteenth Philippic, exalting the success and praising the two consuls and young Caesar Octavian.[1] Nevertheless, the battle was not decisive and the campaign continued. The two armies fought again seven days later (21 April) at the Battle of Mutina, which forced Antony to abandon the siege of the city and retreat westward. Hirtius was killed in the fighting at Mutina; Pansa was still recovering from his wound at Forum Gallorum but died on 23 April in unexplained circumstances.

Background

After the assassination of Julius Caesar, Antony's relations with Caesar's adoptive heir Octavian and the rest of the Roman Senate broke down. At the start of the War of Mutina in late 44 BC, he moved to invest the homonymous city in an attempt to force Decimus Junius Brutus Albinus, the governor of Cisalpine Gaul, to give it up to him in accordance with an illegal law he had passed the previously that year in June.[2]

At the start of 43 BC, the moderate Caesarians Aulus Hirtius and Gaius Vibius Pansa became consuls. Through the early months of the year, Antony's relations with the Senate broke down. Supported by a heterogeneous coalition including Cicero, Octavian, and large potions of the Senate, the consuls were dispatched to relieve Decimus Brutus' forces at Mutina and go to war against Antony. The consuls marched north, joined by Octavian and his private army, which had been legitimised by a grant of imperium pro praetore.[3]

The battle

Mark Antony's plan of attack

In early March 43 BC, Hirtius and Caesar Octavian advanced along the Via Aemilia and reached Bononia; Mark Antony chose to fall back again. For the moment, he sought to strengthen the encircling front around Mutina to contain Decimus Brutus. In fact, neither Hirtius nor Octavian were seeking an immediate battle; they had two of Caesar's legions that had abandoned Antony and three legions of recalled veterans gathered by Octavian in Campania, but for the moment they were waiting for the other consul Vibius Pansa, who left Rome on 19 March, to return along the Via Cassia with four legions of recruits that had been quickly mobilized in January 43 BC.[4]

When Mark Antony became aware of the approach and imminent concentration of his enemies, he set out to take the initiative and move on to the attack as soon as possible. At first, Antony tried to hasten the battle and gain a decisive victory against the forces of Hirtius and Octavian. After leaving a part of his troops behind to detain Decimus Brutus at Mutina, he brought up the bulk of his forces, consisting of four veteran legions and large contingents of cavalry, near his two opponents' camp, harassing them with continuous skirmishes. Hirtius and Octavian, however, did not leave their camp but continued to await Pansa's arrival.[5]

Mark Antony then decided on a new plan: having learned of the arrival of scouts from Vibius Pansa's legions along the Via Aemilia from Bononia, Antony thought he could easily attack and destroy them with his veterans. He also counted on the arrival of three legions from the south, recruited by his capable lieutenant Publius Ventidius Bassus from among Caesar's veterans settled in Picenum.[5] Antony decided to leave part of his forces under the command of his brother Lucius Antonius to hold Decimus Brutus in check, and engage Hirtius and Octavian with a feigned attack on their camp, while moving against Pansa's troops under cover of darkness with his best legions.[5][6]

Because of the uneven and marshy terrain near Forum Gallorum through which the antagonists would have to pass, Mark Antony could not deploy his excellent cavalry forces, but decided to attack by sending Legiones II Gallica and XXXV into the marshes and deploying his praetorian cohorts[7] and those of Marcus Junius Silanus along the main road (Via Aemilia) over the marshy ground.[8] The legionaries were deployed in the shelter of the reeds of the marshes at the point where the main road was narrowest; cavalry units and light infantry moved forward along the Via Aemilia to harry Pansa's troops and draw them into the trap.[9]

Caesar Octavian and Aulus Hirtius had expected the legions of Vibius Pansa to arrive before attacking the forces of Mark Antony. When they learned of the approach of the other consul's four legions, they attacked the legate Servius Sulpicius Galba, one of Caesar's killers, with the Caesarian veterans of the Legio Martia led by the energetic Decimus Carfulenus[10][11] and the personal praetorian cohorts of Caesar Octavian[7] and Aulus Hirtius.[12] Carfulenus and Galba moved in the darkness eastwards along the Via Aemilia and passed through Forum Gallorum; Pansa and Carfulenus made a junction in the night of 14 April 43 BC and started marching at dawn along the road with the pugnacious Legio Martia, five cohorts of recruits, and the praetorian cohorts of Caesar Octavian and Hirtius. In the marshes on either side, the first signs of the enemy were spotted, and presently Antony's praetorian cohorts appeared to block the main road.[13]

The battle in the marshes

The Legio Martia and Vibius Pansa's recruits suddenly stood threatened in front of and alongside Antony's legions. The experienced legionaries did not lose their cohesion, but accepted battle after sending back the cohorts of recruits that were deemed unsuitable for the fight by the Caesarian veterans of the Martia.[13] While the praetorian cohorts of Antony and Caesar Octavian fought sharply along the main road, the Martia veterans split into two parts and, under the command of Pansa and Carfulenus, ran into the marshes to join the battle. Carfulenus led eight cohorts of the Legio Martia into the swampy soil to the right of Via Aemilia, while in the marshes on the left side of the road, the consul Pansa commanded the other two cohorts of the legion, reinforced by Aulus Hirtius' praetorian cohorts. Mark Antony's veterans of Legio XXXV attacked the eight cohorts of the Martia while the entire Legio II moved against the two cohorts under the command of Vibius Pansa to the left of Via Aemilia.[14]

The fighting between the Caesarian veterans of both parties was dramatic and bloody; in his history, Appian describes the particular bitterness of the two parties to a fratricidal struggle.[13] Mark Antony's Caesarians were angry at the defection of the legionaries of the Legio Martia, now allied with the Senate, while the latter legion wanted to take revenge for the decimations and other punishments inflicted on them at Brundisium. Both sides believed that they could obtain a decisive victory, as the veterans' military pride increased the fury of the fight.[13]

The clash between the Caesarian veterans on the two sides took place in a dark silence: without battle-cries or exhortations, the legionaries fought hand-to-hand in a frontal collision between their massed ranks in the swamps and valleys. The legionaries' fratricidal carnage was interrupted only by short breaks used to tighten their formations. The veterans knew their job well; without the need for encouragement, they continued the struggle with tenacity and obstinacy. The mutual slaughter with drawn blades impressed Pansa's inexperienced recruits, who watched the deadly and silent action of the Caesarian legionaries on both sides.[15][16]

This fierce battle between the veterans continued in the swamps, initially without decisive results. On the right wing, the eight cohorts of the Legio Martia under the command of Decimus Carfulenus managed slowly to gain ground, while Antony's Legio XXXV gradually retreated in good order.[17] On the left wing, on the other hand, the other two cohorts of the Legio Martia and the praetorian cohorts of Hirtius, under Pansa's command, first offered a stiff resistance but then began gradually to fold before Antony's entire Legio II.[17] The battle finally turned to the favour of Antony's forces: in the centre along the Via Aemilia, Antony and Silanus' praetorian cohorts prevailed in a brutal clash with Caesar Octavian's praetorian cohorts, which were completely destroyed.[14][17]

In the marshes to the right of the highway, the legionaries of the Martia, who were isolated some 500 paces in advance, were threatened by Antony's Moorish cavalry; Decimus Carfulenus had fallen mortally wounded, and the veterans began to fall back while still repulsing the cavalry's assaults. Exhausted, the legionaries of Antony's Legio XXXV did not at first pursue the retreating enemy.[14] In the marshes to the left of the Via Aemilia, the consul Vibius Pansa suffered a serious injury while fighting on the line; his wound from a javelin shook the two cohorts of the Legio Martia. While the injured consul was transferred to Bononia, the Antonian veterans of Legio II finally put the two cohorts to flight; they now began to fall back in disorder, sowing panic in the ranks of Pansa's raw recruits, whose two legions had been kept far back in reserve.[17] At the sight of the apparent collapse of the veterans of the Legio Martia, the new recruits scattered, falling back to camp in disorder.

Mark Antony's legionaries hastened to pursue the enemy, inflicting heavy losses on the veterans and new conscripts as they fled back towards their camp. The survivors of the Legio Martia actually remained outside the camp and by their presence dissuaded the Antonian legionaries from attacking further. The remnants of the Senatorial legions were virtually trapped inside their camps, and the Antonian veterans would likely force them to surrender in the event of prolonged siege, but Mark Antony was concerned about losing time, fearing that the situation would deteriorate in Mutina in case Hirtius and Octavian's legions sought to break his siege there. Antony therefore felt that he could not stay on the battlefield and decided to return with his forces to the city.[18] In the afternoon, Antony's two victorious legions began to return westward along Via Aemilia in the direction of Mutina. The soldiers were tired but euphoric after apparently achieving a brilliant success.[19][20]

The second phase of the battle

Vibius Pansa, while leading his recruits into battle in the marshes of Forum Gallorum, where he was later seriously injured, had at the same time sent messengers to the other consul, Aulus Hirtius, to inform him of the unexpected battle with the Antonians and their difficult situation. Hirtius was about sixty stadia (c. 11 km) from the battlefield. He decided at once to march to Pansa's aid with the Legio IV Macedonica, the other Caesarian legion that had defected at Brundisium. These fresh troops moved quickly and, in the late afternoon of 14 April 43 BC, came unexpectedly into contact with the legions of Mark Antony who, exhausted after the tough battle, marched in the direction of Mutina in poor order and heedless of danger in their front.[21][22]

The IV Macedonica led by Aulus Hirtius, experienced and well-rested, came to the attack in tight formation against Antony's disorderly and tired troops. Despite attempts at resistance and instances of bravery, the Antonian legions could not withstand the assault, but suffered heavy losses and disintegrated under the attacks of Hirtius' Caesarian.[21][23] The Antonian legions disintegrated, scattering into the marshes and nearby forests; two eagles and sixty other standards were captured by their enemies.[24] Only with great difficulty could Mark Antony rally the remnant with the help of the cavalry, which managed to round up the soldiers during the night and bring them back to camp near Mutina.[21] Aulus Hirtius, hindered by darkness and wary of being lured into a trap, chose not to pursue the defeated Antonian legions.[23] Thus ended the long battle of Forum Gallorum. The marshes were covered with arms, trunks, horse remains, corpses of legionaries of the two sides perceived in the alternate fights.[21][25]

Caesar Octavian's direct role on the day of the battle, 14 April 43 BC, had been minimal. The propraetor held his ground with the other three legions available in their camps, busying themselves with checking and repulsing the faint diversionary attacks led by Lucius Antonius on his brother's instructions.[6][23] Despite taking a lesser role than the two consuls Hirtius and Pansa, he was acclaimed as imperator on the field by his troops.[26]

Aftermath and assessment

Although the Battle of Forum Gallorum ended without a decisive victory for either of the two parties,[27] at the end of the day, Mark Antony's bold plan had been foiled and the two consuls' Senatorial forces had reversed the disastrous outcome of their initial clash, thanks to the decisive intervention of Caesar's legionaries now serving Caesar Octavian—the famous "heavenly legions" exalted by Cicero.[28] The fighting, however, was extremely fierce and bloody. In the first phase, according to Appian, more than half of Vibius Pansa's forces and Octavian's entire praetorian cohort were destroyed by the Antonian veterans; the latter were then decimated in turn, losing half of their forces before finding escape in fields around Mutina. The losses to Aulus Hirtius' legion in the second phase were, however, light.[21]

The first news of the battle that reached Rome of the battle was uncertain, provoking doubts and consternation among the Republican Senators grouped around Cicero. The letter sent by Aulus Hirtius with the news of the triumphant victory and a personal account by Servius Sulpicius Galba, addressed to Cicero, raised morale and aroused euphoria among Antony's Senatorial enemies. After a few days, on 21 April 43 BC, Cicero pronounced in the Senate the triumphalist Fourteenth Philippic, in which he exalted the victory, called even for fifty days of public thanksgiving, and praised above all the two consuls Aulus Hirtius and Vibius Pansa, while somewhat minimizing the contribution by Caesar Octavian.[29] During the session, Cicero also gave the news of Vibius Pansa's injury, but the latter's life did not seem to be in danger.[30] On the morning of 23 April, however, the consul died in circumstances that have never fully been explained. His doctor Glyco was briefly arrested on suspicion of poisoning Pansa, and the rumour spread, later recorded by some ancient historians such as Suetonius and Tacitus, that Octavian had been directly responsible for the sudden death of the consul, whose wound had not seemed serious.[31][32]

On 21 April 43 BC, while Cicero pronounced his last invective against Antony, the Battle of Mutina was bitterly joined. That engagement decided the outcome of the Mutina campaign through the victory of the coalition between the republicans and Octavian's Caesarians, the death of the other consul Hirtius, and the definitive retreat of Mark Antony with the consequent lifting of the siege of Decimus Brutus.[33] The Senatorial victory was, however, to prove ephemeral, for soon Caesar Octavian, alone in command since the two consuls' providential but suspicious demise, would break off his alliance with the senatorial Ciceronian faction in an abrupt realignment of forces that resulted in the formation of the Triumvirate with Mark Antony and Marcus Aemilius Lepidus.[34]

Note

- ↑ Cicero, Phil. XIV, 37.

- ↑ Syme (2014), pp. 110–43.

- ↑ Syme (2014), pp. 182–93.

- ↑ Syme (2014), pp. 189 and 193.

- 1 2 3 Ferrero (1946), p. 211.

- 1 2 Dio, XXXXVI, 37.

- 1 2 Appian, III, 66.

- ↑ Cowan (2007), pp. 13–14.

- ↑ Ferrero (1946), p. 212.

- ↑ Canfora (2007), p. 41.

- ↑ Carfulenus had served under Caesar in the Alexandrine War. He is cited as "a man of exceptional personality and field experience" (Bellum Alexandrinum, 31).

- ↑ Cowan (2007), p. 13.

- 1 2 3 4 Appian, III, 67.

- 1 2 3 Cowan (2007), p. 14.

- ↑ Appian, III, 68.

- ↑ Syme (2014), p. 194.

- 1 2 3 4 Appian, III, 69.

- ↑ Dio, XXXXVI, 37–38.

- ↑ Appian, III, 69–70.

- ↑ Ferrero (1946), pp. 212–213.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Appian, III, 70.

- ↑ Ferrero (1946), pp. 212–213. The author writes that the legions that Aulus Hirtius led into battle were two: the IIII and the VII.

- 1 2 3 Ferrero (1946), p. 213.

- ↑ Canfora (2007), p. 42.

- ↑ Canfora (2007), pp. 47–48.

- ↑ Syme (2014), p. 193.

- ↑ Ferrero (1946), pp. 213–214.

- ↑ Syme (2014), p. 206.

- ↑ Canfora (2007), pp. 42–44.

- ↑ Cicero, Phil. XIV, 26.

- ↑ Canfora (2007), pp. 53–55.

- ↑ Tacitus, Ann. I, 10; Tacitus writes of "shedding poison on the wound" of Pansa and the "machinations of the same Augustus."

- ↑ Ferrero (1946), p. 214-215.

- ↑ Syme (2014), pp. 209–212.

References

Ancient sources

- Appian of Alexandria. Historia Romana (Ῥωμαϊκά). Vol. Civil Wars, book III. Archived from the original on 2015-11-20. Retrieved 2020-03-26.

- Cassius Dio Cocceianus. Historia Romana. Vol. Book XXXXVI.

- Pseudo-Caesar. Bellum Alexandrinum.

- Marcus Tullius Cicero. Philippicae. Vol. XIV.

- Gaius Suetonius Tranquillus. De vita Caesarum. Vol. Vita divi Augusti.

- Publius Cornelius Tacitus. Annales. Vol. Book I.

Modern sources

- Canfora, Luciano (2007). La prima marcia su Roma. Bari: Editori Laterza. ISBN 978-88-420-8970-4.

- Cowan, Ross (2007). Roman Battle Tactics, 109 BC – AD 313. London: Osprey. ISBN 978-1-84603-184-7.

- Encyclopædia Britannica

- Dictionary of the Roman Empire

- Ferrero, Guglielmo (1946). Grandezza e decadenza di Roma. Volume III: da Cesare a Augusto. Cernusco sul Naviglio: Garzanti.

- Osprey Essential Histories, Caesar's Civil War

- Syme, Ronald (2014). La rivoluzione romana. Turin: Einaudi. ISBN 978-88-06-22163-8. (Italian translation)