| Batman: Anarky | |

|---|---|

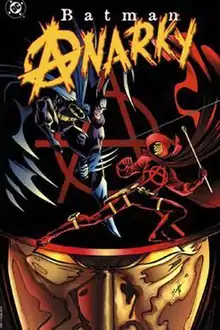

Cover of Batman: Anarky (1999), trade paperback edition; art by Norm Breyfogle and colors by Sherilyn van Valkenburgh. | |

| Publisher | DC Comics |

| Publication date | "Anarky in Gotham City" November - December 1989 "Anarky: Tomorrow Belongs To Us" Summer 1995 "Anarky" July - August 1995 "Metamorphosis" May - August 1997 |

| Genre | |

| Title(s) | "Anarky in Gotham City" Detective Comics #608-609 "Anarky: Tomorrow Belongs To Us" The Batman Chronicles #1 "Anarky" Batman: Shadow of the Bat #40-41 "Metamorphosis" Anarky vol. 1, #1-4 |

| ISBN | ISBN 1-56389-437-8 |

| Creative team | |

| Writer(s) | Alan Grant |

| Penciller(s) | "Anarky in Gotham City" Norm Breyfogle "Anarky: Tomorrow Belongs To Us" Staz Johnson "Anarky" John Paul Leon "Metamorphosis" Norm Breyfogle |

| Inker(s) | "Anarky in Gotham City" Steve Mitchell "Anarky: Tomorrow Belongs To Us" Cam Smith "Anarky" Ray McCarthy "Metamorphosis" Josef Rubinstein |

| Letterer(s) | "Anarky in Gotham City" Todd Klein "Anarky: Tomorrow Belongs To Us" Bill Oakley "Anarky" John Costanza "Metamorphosis" John Costanza |

| Colorist(s) | "Anarky in Gotham City" Adrienne Roy "Anarky: Tomorrow Belongs To Us" Phil Allen "Anarky" Sherilyn van Valkenburgh "Metamorphosis" Noelle Giddings |

Batman: Anarky is a 1999 trade paperback published by DC Comics. The book collects prominent appearances of Anarky, a comic book character created by Alan Grant and Norm Breyfogle. Although all of the collected stories were written by Alan Grant, various artists contributed to individual stories. Dual introductions were written by the creators - both of whom introduce the character and give insight into their role in Anarky's creation and development.

Featured as an antagonist in various Batman comics during the '90s, stories based on the character were highly thematic, political, and philosophical in tone. The majority of the collected stories ("Anarky in Gotham City", "Anarky: Tomorrow Belongs to Us", "Anarky") are influenced by the philosophy of anarchism, while the final story ("Metamorphosis") is influenced by Frank R. Wallace. Although anti-statism is the overarching theme of the collection, other concepts are explored. Anarky's characterization was expanded throughout the stories to present him first as a libertarian socialist and anarchist, and in the final story as a vehicle for explorations into atheism, rationalism, and bicameral mentality. Literary references are also utilized throughout the collected stories to stress the philosophical foundations of the character. The collection also tracks the character's evolution from a petty, street-crime fighting vigilante, to a competent freedom fighter in opposition to powerful forces of evil.

Critics have positively received some of the stories within the collection, analyzing Anarky as a unique force for political commentary and discussion within DC Comics' storytelling. However, the expansive growth of the character's unique abilities and characterization has also fueled criticism as having overpowered the character beyond suspension of disbelief.

Collection history

Character creation and development

In the late '80s, writer Alan Grant considered drawing upon his own anarchist sympathies and utilizing them for a character in the Detective Comics, which he was writing at the time. In a bid to replicate the success of Chopper, a rebellious youth in the "Judge Dredd" comic strip, Grant created Anarky as a twelve-year-old political radical, far more mature, violent, and intelligent than his peers. Influenced by V, the protagonist of Alan Moore's V for Vendetta, Grant's only instructions to illustrator Norm Breyfogle were that Anarky be designed as a cross between V and the black spy from Mad magazine's Spy vs. Spy.[1] In his own intro to the collection, Norm Breyfogle explains that, pressured by deadlines, and failing to recognize the character's long-term potential, he "made no preliminary sketches, simply draping [Anarky] in long red sheets". As the character was intended to wear a costume that disguised his youth, Breyfogle designed a crude "head extender" that elongated Anarky's neck, creating a jarring appearance.[2]

The first appearance of Anarky was in "Anarky in Gotham City", Detective Comics #608, in November 1989. Grant's initial script portrayed Anarky as vicious, killing his first victim. Dennis O'Neil, then editor of Detective Comics, balked at this proposal, believing that the depiction of a twelve-year-old becoming a murderer was morally reprehensible. Grant consented to O'Neil's request that the script be changed, and rewrote it to portray Anarky as violent, but non-lethal. Grant later expressed relief with this early decision, coming to believe that "Anarky would have compromised his own beliefs if he had taken the route of the criminal-killer".[1]

(Anarky is) a philosophical action hero, an Aristotle in tights, rising above mere "crime-fighter" status into the realm of incisive social commentary.

Norm Breyfogle, Batman: Anarky introduction, June 1998.[2]

Although Grant had not created Anarky to be used beyond the two-part debut story, the positive reception Anarky received among readers and his editor caused Grant to change his mind. In the following years, Grant developed the character to contrast with typical heroic characters. Based on a theme of philosophy, Anarky was not given a tragic past - a common motivator in comic books - but was instead given motivation by his convictions and beliefs. In his introduction to the trade paperback, Grant compared this with Batman, who fought crime due to personal tragedy. Grant also contrasted Anarky with common teenage superheroes. Rejecting the tradition established by Stan Lee and Jack Kirby, Grant avoided saddling Anarky with personal problems, a girlfriend, or social life. This was intended to convey the idea that Anarky was self-assured in his goals. The singular problem the character did have was tending to his secret activities while escaping from juvenile detention centers, or hiding his actions from his parents, who did not approve of his activism. These aspects of the character were incorporated into "Anarky: Tomorrow Belongs to Us" and "Anarky", each respectively published in 1995, as this period of the character's portrayal came to a conclusion.[1]

Leading into the character's next phase of publication, the Anarky limited series, "Metamorphosis", was published in 1997. Coinciding with Alan Grant's transition from the philosophy of anarchism to Neo-Tech, Grant chose to re-characterize Anarky accordingly.[3] Norm Breyfogle also took the opportunity to redesign Anarky's costume, excising the head extender with the explanation that the character had grown up and filled out his costume.[2] The golden mask was also redesigned as a reflective but flexible material that wrapped around Anarky's head, allowing for the display of facial movement and emotion which had previously been impossible due to the inflexible metal that the first mask was made of.[4]

With the success of the limited series, Darren Vincenzo, an assistant editor at DC Comics, and the editor of the Anarky mini-series, promoted the continuation of the comic into a regular monthly title.[5] In the lead-up to the publication of both ventures, Breyfogle and Grant wrote introductory essays intended for the trade paperback in June 1998. Breyfogle also continued the character costume adjustments he'd begun for the limited series. Fully redesigning the suit, Breyfogle retained the red jumpsuit, flexible gold mask, and hat, but eliminated the red robes in favor of a more traditional outfit. New additions to the suit included a red cape, golden utility belt, and a single, large Circle-A insignia across the chest, akin to Superman's iconic "S" shield. Batman: Anarky was published several months later with the new costume featured on the cover page, despite the fact that it does not appear in any of the collected stories.

Collected comics

It's often difficult to view one's older work, but, like old diary entries of good times, the overall nostalgic pleasure that these stories provide me never diminishes.

Norm Breyfogle, Batman: Anarky introduction, June 1998.[2]

Published on February 22, 1999, Batman: Anarky collected nine Batman-related comic books, comprising four unique stories connected by their featured character: Anarky. The collected material, originally published in 1989, 1995, and 1997, includes Anarky's first appearance; the revelation of Anarky's origin story; and Anarky's first limited series.

The first story, "Anarky in Gotham City", was published in Detective Comics #608 and #609.[6] Although Anarky was not intended to be used beyond this debut story, the positive reception the character received convinced Alan Grant to continue using the character in future issues. The next collected story, "Anarky: Tomorrow Belongs to Us", was published in The Batman Chronicles #1.[7] Published quarterly, this comic anthology collected short stories with an emphasis on Batman supporting characters. The eponymous story, "Anarky", was originally published in Batman: Shadow of the Bat #40 and #41.[8] The only storyline in the collection which is not self-contained, it alludes to other story elements taking place within the Batman mythos at the time, including the temporary resignation of Alfred Pennyworth and the mid-life crisis of James Gordon. The story reveals Anarky's origin story and includes the character's faked death scene—an important plot point in the last collected story.

The last of these four stories, "Metamorphosis", was published as a spin-off limited series between May and August of 1997,[9] as a result of a request Norm Breyfogle made to DC Comics for employment following the comic book crash of the mid-1990s. Darren Vincenzo suggested multiple projects which Breyfogle could take part in, among them an Anarky mini-series written by Alan Grant, which was eventually the project decided upon.[5] The Anarky limited series was received with positive reviews and sales, and was later declared by Grant to be among his "career highlights".[10] With the continuation of the series as an ongoing monthly in 1999, these four issues were retroactively categorized as the first Anarky volume. Both volumes of Anarky are unique as the only comic books ever thematically based on the philosophy of Neo-Tech.[3]

Collection contributors

Collecting four stories, Batman: Anarky gathers the work of a total of sixteen contributors employed by DC Comics over the course of eight years. While all of the collected stories were written by Alan Grant, contributing pencillers include Norm Breyfogle, Staz Johnson, and John Paul Leon, with various artists assisting as inkers, colorists, and letterers. Each of the artists who worked on the Anarky limited series, "Metamorphosis", would later return to continue their work on the Anarky ongoing series in 1999.

.jpeg.webp)

Alan Grant, a writer from Scotland, got his start on 2000 AD as an assistant writer for John Wagner. Grant rose to prominence as an equal of Wagner's in the creation of Judge Dredd comic strips. These stories were noted favorably for their use of socio-political commentary and satire. Together, the duo acquired employment with DC Comics. Dennis O'Neil assigned them to Detective Comics in 1988, hoping they would bring their gritty, violent take on Judge Dredd to Batman storylines. Soon after, Wagner left the company, leaving Grant to continue the run on his own. Drawing on his work for Judge Dredd, Grant began injecting social commentary into the comic book, and avoided using common Batman rogues in favor of his own creations. Some of these villains were influenced by characters from the Judge Dredd universe.[11] Anarky was conceived singularly by Grant as a result of these circumstances, and Grant's own intellectual and philosophical meditations influenced the portrayal of the character over the following years.[3]

Collaborating with Grant during these early years on Detective Comics was illustrator Norm Breyfogle, who designed and later modified the appearance of Anarky.[2] Frequently noted as the co-creator of the characters Alan Grant conceived of during their Detective Comics run together, Breygole has confessed to personally believing that this credit is unwarranted. Contending that he merely drew the characters Grant conceived, he has nonetheless accepted credit for the development of Anarky, as he eventually took part in frequent correspondence over fax-transmission with Grant during the Anarky limited series. These faxed letters to each other fueled discussion and debate regarding the character and plot development, and influenced both men in their later work.[12] Of the collected illustrators, he is the only artist to have penciled more than a single story for the character.

Other contributing illustrators include Staz Johnson, who after penciling "Anarky: Tomorrow Belongs to Us", would go on to work exclusively for DC Comics for several more years. Illustrator John Paul Leon collaborated on "Anarky" in 1995, just a year after he received his Bachelor's in Fine Arts from School of Visual Arts in 1994.[13] Steve Mitchell, the regular inker for Detective Comics during Grant and Breyfogle's collaborative run, inked "Anarky in Gotham City". Cam Smith, Ray McCarthy, and Josef Rubinstein completed the ink work for "Anarky: Tomorrow Belongs to Us", "Anarky", and "Metamorphosis, respectively.

Todd Klein, an award winning letter and logo designer, mainly worked for DC Comics during the 1980s. A freelancer, Klein designed logos and title headers for various comics, while at other times created lettering for many of the decades most prominent titles.[14] Klein would also create the lettering for Alan Grant's run on Detective Comics, where he would work together with Grant and Breyfogle in the creation of "Anarky in Gotham City". Bill Oakley, a letterer well respected among his peers for his distinctive style,[15] contributed to "Anarky: Tomorrow Belongs To Us". John Costanza, who has won awards on multiple occasions in the field of comic book lettering,[16][17] contributed to both "Anarky" and "Metamorphosis".

Adrienne Roy, a colorist predominantly associated with many of the Batman franchise comics of the late '80s and early '90s, provided coloring for "Anarky in Gotham City". Phil Allen was tapped for "Anarky: Tomorrow Belongs To Us", while Sherilyn van Valkenburgh colored "Anarky", as well as the Batman: Anarky cover illustration. After serving as color editor for Milestone Media between 1992 and 1995, Noelle Giddings joined DC Comics and produced the coloring for "Metamorphosis".

Stories

"Anarky in Gotham City"

During a late night drug raid, Batman, the vigilante protector of Gotham City, discovers that the drug dealer he was tracking has already been assaulted and left for police to find. Next to his unconscious body is a spray painted Circle-A, announcing the arrival of a new vigilante, Anarky. Anarky continues his war against crime by targeting a business owner dumping pollutants in a river. Batman recognizes his M.O. and realizes he is attacking people based on the complaints raised in letters to the editor in a local newspaper.[18] He alerts the police, who plan stake-outs at several events based on the letters. When Anarky strikes next, however, it is at a construction site unlisted in the paper. Anarky rallies the homeless to riot in response to the destruction of their "Cardboard City", which has been bulldozed to build a new bank. Batman arrives but is attacked by the homeless mob so that Anarky may flee. The mob includes Legs, a homeless Vietnam veteran who Alan Grant would utilize as a partner for Anarky in future stories. Batman eventually catches Anarky, revealing him to be a disguised, twelve-year-old paperboy named Lonnie Machin. As a child prodigy with extensive knowledge of both radical philosophy and improvised munitions, Lonnie was confident that violent change was necessary to improve social conditions. Batman condemns his actions, but expresses admiration for his idealism.[19]

"Anarky: Tomorrow Belongs to Us"

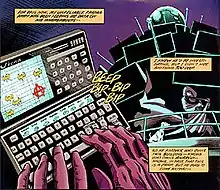

While serving time in a juvenile correction facility, Lonnie Machin creates a makeshift hologram projector and two-way communicator, and uses it to leave the impression that he is still held in detention. He then escapes and sabotages a politician's ad campaign in order to promote anti-electoral propaganda, with the assistance of Legs, who acts as a diversion against a local guard. Anarky uses his communicator during his adventure to carryout a political dialogue with his fellow detainees, narrowly returning before guards notice his absence.[20]

"Anarky"

Several months after the events of "Anarky: Tomorrow Belongs to Us", Lonnie Machin has been released from juvenile detention on parole, and uses the internet to create a company, "Anarco". Through Anarco, Machin sells anarchist literature online, secretly acquiring millions of dollars. He channels this wealth through a proxy organization, "The Anarkist Foundation", to donate the funds to political groups he supports, including gun protesters, eco-warriors, and clean energy lobbies. Meanwhile, he successfully hides this activity from his parents, Mike and Roxanne Machin, who do not approve of his behavior, believing themselves to have failed to raise their son properly. Their relationship with him becomes strained, as they attempt to rehabilitate him into normality, while he wishes they would be proud of his vigilante activism. Continuing his secret philanthropy, he supports Malochia, a self-proclaimed "prophet of doom" who spreads a message that current social conditions are intolerable. Anarky comes to suspect that this "prophet" has an ulterior motive, and hires private detective, Joe Potato, to investigate his actions. Meanwhile, Batman and Robin have also placed Malochia under their watch, and discover his connections to Lonni Machin. Anarky, Joe Potato, and Batman confront Malochia, but are each captured and tied to a blimp.[21] The blimp is loaded with high explosives and set to detonate near the center of the city. Malochia hopes this act will set into effect his own delusional predictions of calamity. Anarky and Joe Potato revive and steer the blimp towards the water front, still set to explode. Anarky releases both Potato and Batman into the water, but is tangled in ropes and presumably caught in the explosion. During the story, Lonnie's parents find a letter he wrote in the event of his death. The letter acts as a literary device to explain his origin as Anarky and the personal reasons behind his decision to become a vigilante. Lonnie Machin's father and mother, Mike and Roxanne raise their son to be a happy child, and encourage his intelligence and thirst for knowledge with trips to bookstores. Through his research, Lonnie eventually grows to become the political radical, Anarky.[22]

"Metamorphosis"

"Metamorphosis" chronicles Machin's narrow survival of an explosion and use of the confusion in its aftermath to fake his death. Several months later, he is now stated to be fifteen-years old and has begun a new plan to liberate the world of government. As Anarky, he attempts to create a device which will emit beams of light on frequencies which will trigger the human brain of all who see it. The people will then be "de-brainwashed" of all the social constraints which society has placed on the individual. Utilizing a makeshift teleportation device capable of summoning a boom tube, he begins a quest to capture the power sources his invention will need: the madness of Etrigan,[23] the evil of Darkseid,[24] and the goodness of Batman.[25] Desiring to tempt Batman into confronting him, Anarky successfully lures Batman's attention by hiring Legs and other homeless men to monitor Batman's movements. During the confrontation between Anarky and Batman, the device is damaged. Thus, when Machin activates it, it only affects himself. The vision that follows reveals what may have happened if he had succeeded, with nightmarish consequences. In the hallucination, the slightest infraction against a smooth-running society is met with banishment to a prison-city. The effects of his machine eventually wear off, and the most dangerous elements of the prison escape, causing havoc. The conclusion Anarky draws from this is that if society is to change, individuals must accept that change voluntarily.[26] When Batman turns off the machine, Anarky awakens and promptly escapes, vowing to continue his mission, "until they all learn to choose for themselves..."[27]

Reception

Critics have positively received some of the stories within the collection, analyzing Anarky as a unique force for political commentary and discussion within DC Comics' storytelling. However, the expansive growth of the character's unique abilities and characterization has also fueled criticism as having overpowered the character beyond suspension of disbelief.

Greg Burga, of PopCultureShock.com, critiqued Anarky as "one of the more interesting characters of the past fifteen or twenty years ... because of what he wants to accomplish". He also analyzed the appeal of the character, considering the philosophy of anarchy "radical and untenable, yet still noble".[28]

In a review of the Anarky mini-series, Anarky was dubbed an "anti-villain", as opposed to "anti-hero", due to his highly principled philosophy, which runs counter to most villains: "In the age of the anti-hero, it only makes sense to have the occasional anti-villain as well. But unlike sociopathic vigilante anti-heroes like the Punisher, an anti-villain like Anarky provides some interesting food for thought. Sure, he breaks the law, but what he really wants is to save the world... and maybe he's right".[29]

Alan Grant later referred to it as one of his favorite projects, and ranked it among his "career highlights".[30]

"Yeah, well see they were taking the point of view that Anarky was created.. well y’see he’s a teenager character, I think he’s 15 or 16… and they were taking the viewpoint that previously the toughest guy I ever had him up against was Batman and suddenly here we have him confronting a demon from hell in issue #1, and in issue #2 he confronts Darkseid who’s the most evil character in the DC universe".[3]

"Yeah, and when I put that in my proposal for issue two the editor actually complained .. not about my handling of the character of Darkseid, but about the fact that Anarky was able to stand up to a Darkseid and was able to argue with him".[3]

"Yeah. Like an animal, that’s it exactly. And they took great exception to this. Their line on it was that Darkseid is evil because he is evil. And I said, 'that can’t be right'. He’s evil because he wants to be evil. It sounds like such a minor sticking point when we’re discussing it like this, but at the time it caused me endless headaches trying to figure out how I was gonna get these editors to accept exactly what it was I was trying to tell them".[3]

"...it was more for the sake of the reader who haven’t had access to any Neo-Tech literature whatsoever, and what I’m saying, for them is actually radically different than what they’re used to believing..."[3]

"So I wasn’t able to take [Neo-tech] quite as far as I would have liked it. I was also very angry with them about the advertising for the comic. The whole point of this four issue miniseries is to make the point that the end doesn’t justify the means. However, the only slogan for the ad campaign is that the ends justify the means: "His name is his goal". And I called them up and I said, 'This isn’t right. You’ve taken this the wrong way 180 degrees. Don’t you understand what this book is about?'

And instead of getting a confession, 'okay, we’re sorry, we made a mistake', and seeing what they can do to rectify it... What I got was well uh, 'no we don’t really understand what we’re reading'. So what we’re dealing with here is that they brushed up against Neo-Tech, but then just went on their way... back into the oblivion, where they don’t need to think for themselves..."[3]

"Well I’ll do my best to get address onto the last issue. I’m actually expecting a call this week and just to jump ahead to the end of issue four, well like I told you, for political reasons, Batman had to, well being the hero, had to beat Anarky who is looked on by the DC people as being a villain. So Anarky was wrong and confessed... Well his mistake I had to take as being believing that he has the right to fuse other people’s brains where he didn’t have that right at all obviously". [3]

Yeah. So anyway the book ended with Anarky cleverly escaping from Batman and disappearing into the city. And over his disappearance were the lyrics to the John Lennon song, I don’t know if you know that song.. It’s basically, 'Just imagine there’s no heaven, it’s easy cuz it’s true', y’know there’s no god, just me and you". [3]

"And stuff like that and it made a very nice ending for the story, it’s a very rounded ending. Because you wouldn’t have thought of John Lennon’s work in that Neo-Tech context". [3]

"However, DC comics went to the owner of the songs and they said we couldn’t use the lyrics unless paid some sort of massive fee... I don’t know what it was cause it’s editorial that usually handles that. So all I knew was I got a phone call saying, "We spoke to Northern Songs, they want too much money, you’re gonna have to rewrite the end of the book". Which I hadn’t been expecting at all". [3]

"Lonnie Macon [sic] just gets loonier and loonier with each issue of Anarky".[31]

"...resulting in an atypical confrontation against Darkseid".[31]

"...though Mr. Grant's story explores complex arguments, the characters do not lose themselves in the discussion; rather Mr. Grant's selection of players enhances the theme".[31]

"Because comic books feature characters who embody the two extremes, the medium is an ideal arena for Mr. Grant's philosophic foray".[31]

"Within the drab brown setting--courtesy of Noelle Giddings, [Norm Breyfogle] establishes the seemingly chaotic madness of Apokolips".[31]

"Though Darkseid controls all, he permits a more disorganized sadism and sense of decay throughout his world, but as we discover in the appropriately jarring segue, Anarky ironically demands a septic and more advanced order".[31]

"Mr. Breyfogle further proves himself the ideal choice by clouding Anarky's villainy with traditional heroic poses thus granting the illusion of a champion as Lonnie confronts tried and true fiends--all of whom we discover may actually argue for relativity or the inherent inhumanity of man".[31]

This steady evolution in Anarky's abilities was criticized in a review of the Anarky ongoing series, by Fanzing contributor Matt Morrison. Morrison saw it as having overpowered the character, preventing the suspension of disbelief that was previously possible for a character still described as in his mid-teens, and contributing to the failure of the series.[32]

"Now, I had a bad feeling about this book from the start. I liked most of his early appearances, but at the time his book came out he had become an uber-god: a human who has nothing but a lot of technology and their wits and still manages to take on most of the metahumans on the planet, much like Prometheus or Batman as written by Grant Morrison".[32]

"I liked the original concept behind Anarky: a teenage geek who reads The Will to Power one too many times and decides to go out and fix the world. But the minute he wound up getting $100 million in a Swiss Bank account, owning a building, impressing Darkseid, getting a Boom Tube and was shown as being able to outsmart Batman, outhack Oracle and generally be invincible, I lost all interest I had in the character".[32]

Themes

Literary references

Mike Machin dialogue by Alan Grant,"Anarky".[33]He's fifteen years old, for pity's sake! Look at these books--! He should be sneaking copies of Playboy around, not Bakunin and Marx and Ayn Rand!

Within the books, the nature of the character's political opinions was often expressed through his rhetoric, and by heavy use of the Circle-A as a character gimmick. Other themes were often used when Anarky was a featured character in a comic. In early stories, books would often be referenced to express the character's philosophical agenda. The earliest example of this was in the "Anarky in Gotham City" and "Anarky" storylines, in which Anarky makes references to Universe by Scudder Klyce, an extremely rare book, and cites passages within it as having inspired his actions.[34] Various books can be seen in Lonnie Machin's bedroom in the "Anarky" storyline, including tomes named after the ancient Greek philosophers Plato and Aristotle, and the Swedish scientist, Emanuel Swedenborg.[35] Within the same storyline, Anarky's father comments on the political books in the teenager's room, referring to the Russian anarchist, Mikhail Bakunin, German philosopher, Karl Marx and the founder of Objectivism, Ayn Rand.[36] The "Metamorphosis" storyline later continued the theme, displaying an edition of Buckminster Fuller's Synergetics near the story's climax.[37] When asked if he was concerned readers would be unable to follow some of the more obscure literary references, Grant responded that he didn't expect many to do so, but was "pleased to say several did" and reported carrying on a correspondence with at least one reader over the course of several years.[38] Besides books, fluttering newspapers were also used as a literary element to convey ideas, often included in street settings and bearing headlines alluding to social problems such as white-collar crime and poverty.[39] Several newspapers also include the titles of political books on their pages. One page bears the title of Noam Chomsky's series of interviews with David Barsamian, Keeping the Rabble in Line; another Bill Devall's Clearcut: The Tragedy of Industrial Forestry;[40] while a third refers to Urban Indians: Drums from the cities by Gregory W. Frazier.[41]

Philosophical shift

As an antagonist in a limited number of Batman comics during the 90's, Anarky was largely reserved for stories in which Grant wished to press a political point. Early incarnations of Anarky portrayed the character as an anarchist, and were intended to act as a medium for Grant's personal meditations on political philosophy, and specifically for his own anarchist, socialist, and populist leanings. However, according to Grant, anarchists with whom he associated were hostile to his creation of the character, seeing it as an act of recuperation for commercial gain.[42] With libertarian socialism being the primary theme of the first three storylines in the collection, other concepts explored in the stories were informed by the umbrella of anarchist theory. Anti-electoralism and the tactic of non-voting are the dual focuses of "Anarky: Tomorrow Belongs to Us", while economic exploitation, environmental issues, and political corruption are repeatedly referenced in the three remaining stories.

Over the course of several years, Grant's political opinions shifted from libertarian socialism to free market-based philosophies. Alan Grant commented on the philosophical pattern the character's transformation took for a 1997 interview: "Although I haven’t read them in chronological order I would think it would be quite easy to see the parallel between Anarky’s thought processes and my own thought processes".[3] By 1997 he had settled on the philosophy of Neo-Tech, a philosophy developed by Frank R. Wallace. At approximately the same time he was when given the opportunity to write an Anarky mini-series, and so decided to revamp the character accordingly. Grant laid out his reasoning in an interview just before the first issue's publication: "I felt he was the perfect character to express Neo-Tech philosophy because he's human, he has no special powers, the only power he's got is the power of his own rational consciousness".[3] This new characterization was later carried on in the 1999 Anarky ongoing series.

The "Metamorphosis" storyline led the character away from many of the philosophical concepts previously espoused, but the primary theme of the collection remained anti-statism. New emphasis was placed on previously unexplored themes, including the mind, consciousness and bicameral mentality.[43] Anarky's characterization was also expanded to present him as an atheist and rationalist. A recurring theme in "Metamorphosis" was a scene of Anarky expounding philosophy to his pet dog, and indirectly to the reader, for a single page in each part of the story, for a total of four pages.[3] These monologues included an explanation of bicameral mentality,[44] a comparative summary of the political philosophy of Plato and Aristotle,[45] a description of the concept of economic "parasites,"[46] and a final description of how the elimination of irrationality would allow society to progress.[47] Another important theme to the final storyline is a discourse on the nature of evil, as a subplot of the story. Anarky's pursuit, as Grant put it, "...is to find out why anyone would make the decision to be evil". To that end, Grant pitted Anarky against Etrigan and Darkseid with the intention of providing a setting for a series of dialogues on the topic.[3]

Heroic evolution

Anarky dialogue by Alan Grant,"Anarky: Tomorrow Belongs to Us".[48]Batman's misguided. He fights the results of crime, but not the causes. He takes on individual cases... but he fails to see the wider picture!

Aside from the philosophical themes present throughout the collection, the steady progression of Anarky's abilities and enemies is also highlighted. In the earliest stories, Anarky's targets are minor criminals, contrasting with the last story, "Metamorphosis". This final story portrays Anarky facing more dangerous opponents - those who, as Grant wrote, are "virtual embodiments of evil".[1] Anarky's steady growth in fighting ability, technological innovation, and wealth is also documented within the collection. In "Anarky in Gotham City", Lonnie Machin is described as being highly intelligent, but lacking in any other skill.[49] This changed in "Anarky", where he begins developing his skills in hand to hand combat, begins experimenting on his brain to increase his intelligence, and creates a front company to begin amassing money.[50] By the final storyline, Anarky is capable of creating advanced, high tech gadgets and devices, such as a teleportation device;[51] has fused his brain and magnified his intelligence to genius levels;[52] has studied multiple styles of martial arts, and created his own hybrid martial art;[53] and has millions of dollars with which to fund his plans.[54]

The progression of Anarky's abilities was also mirrored by the change in the character's costume. The design shift from an early suit intended to disguise Lonnie's age, to one that fit him more fully, was commented on by Norm Breyfogle, who wrote, "…during his existence he's gained quite a few inches and pounds, filling out his costume! The change from black eyes to white may also be seen as indicating that Lonnie's real eyes now peer out of the mask. He's literally grown into the role!"[2]

Media information

Editions

The DC Comics edition, distributed throughout North America, contained an error on page 130, in which the lettering was removed from a speech balloon. The publication was shipped with a sticker of the missing text, which readers could place over the wordless balloon to complete the page.

- Batman: Anarky (February 2, 1999). New York City, NY: DC Comics, ISBN 1-56389-437-8.

The Titan Books Ltd edition, published several months after the North American release, is distributed throughout the United Kingdom.

- Batman: Anarky (April 16, 1999). London: Titan Books Ltd, ISBN 1-85286-995-X.

Collected issues

The issues collected in the trade paperback are:

- Grant, Alan (w), Breyfogle, Norm (p), Mitchell, Steve (i). "Anarky in Gotham City, Part One: Letters to the Editor" Detective Comics, no. 608 (November 1989). New York City, NY: DC Comics.

- Grant, Alan (w), Breyfogle, Norm (p), Mitchell, Steve (i). "Anarky in Gotham City, Part Two: Facts About Bats" Detective Comics, no. 609 (December 1989). New York City, NY: DC Comics.

- Grant, Alan (w), Johnson, Staz (p), Smith, Cam (i). "Anarky: Tomorrow Belongs to Us" The Batman Chronicles, no. 1 (Summer 1995). New York City, NY: DC Comics.

- Grant, Alan (w), Paul Leon, John (p), McCarthy, Ray (i). "Anarky, Part One: Prophet of Doom" Batman: Shadow of the Bat, no. 40 (July 1995). New York City, NY: DC Comics.

- Grant, Alan (w), Paul Leon, John (p), McCarthy, Ray (i). "Anarky, Part One: The Anarkist Manifesto" Batman: Shadow of the Bat, no. 41 (August 1995). New York City, NY: DC Comics.

- Grant, Alan (w), Breyfogle, Norm (p), Rubinstein, Josef (i). "Metamorphosis, Part One: Does a Dog Have a Buddha Nature?" Anarky, vol. 1, no. 1 (May 1, 1997). New York City, NY: DC Comics.

- Grant, Alan (w), Breyfogle, Norm (p), Rubinstein, Josef (i). "Metamorphosis, Part Two: Revolution Number 9" Anarky, vol. 1, no. 2 (June 1, 1997). New York City, NY: DC Comics.

- Grant, Alan (w), Breyfogle, Norm (p), Rubinstein, Josef (i). "Metamorphosis Part Three: The Economics of The Madhouse" Anarky, vol. 1, no. 3 (July 1, 1997). New York City, NY: DC Comics.

- Grant, Alan (w), Breyfogle, Norm (p), Rubinstein, Josef (i). "Metamorphosis Part Four: Fanfare for the Common Man" Anarky, vol. 1, no. 4 (August 1, 1997). New York City, NY: DC Comics.

See also

- Anarchism and the arts, the tradition of anarchist influence on art mediums, including comics.

- Anarchy Comics, an underground comic anthology created by anarchist cartoonists.

- The Invisibles, a comic book series featuring characters and philosophy partially influenced by anarchist thought.

- Trashman (comics), 1960s underground comix character influenced by anarchist and Marxist philosophy.

References

- Citations

- 1 2 3 4 Grant, Batman: Anarky, p. 3, 4.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Grant, Batman: Anarky, p. 5, 6.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 Kraft, Gary S. (1997-04-08). "Holy Penis Collapsor Batman! DC Publishes The First Zonpower Comic Book!?!?!". GoComics.com. Archived from the original on 1998-02-18.

- ↑ Grant, Batman: Anarky, p. 117.

- 1 2 Carey, Edward (2006-10-10). "Catching Up With Norm Breyfogle and Chuck Satterlee". Comic Book Resources. Retrieved 2007-01-24.

- ↑ Grant, Alan (w), Breyfogle, Norm (p), Mitchell, Steve (i). "Anarky in Gotham City, Part One: Letters to the Editor" Detective Comics, no. 608 (November 1989). New York City, NY: DC Comics.

Grant, Alan (w), Breyfogle, Norm (p), Mitchell, Steve (i). "Anarky in Gotham City, Part Two: Facts About Bats" Detective Comics, no. 609 (December 1989). New York City, NY: DC Comics. - ↑ Grant, Alan (w), Johnson, Staz (p), Smith, Cam (i). "Anarky: Tomorrow Belongs to Us" The Batman Chronicles, no. 1 (Summer 1995). New York City, NY: DC Comics.

- ↑ Grant, Alan (w), Paul Leon, John (p), McCarthy, Ray (i). "Anarky, Part One: Prophet of Doom" Batman: Shadow of the Bat, no. 40 (July 1995). New York City, NY: DC Comics.

Grant, Alan (w), Paul Leon, John (p), McCarthy, Ray (i). "Anarky, Part One: The Anarkist Manifesto" Batman: Shadow of the Bat, no. 41 (August 1995). New York City, NY: DC Comics. - ↑ Grant, Alan (w), Breyfogle, Norm (p), Rubinstein, Josef (i). "Metamorphosis, Part One: Does a Dog Have a Buddha Nature?" Anarky, vol. 1, no. 1 (May 1, 1997). New York City, NY: DC Comics.

Grant, Alan (w), Breyfogle, Norm (p), Rubinstein, Josef (i). "Metamorphosis, Part Two: Revolution Number 9" Anarky, vol. 1, no. 2 (June 1, 1997). New York City, NY: DC Comics.

Grant, Alan (w), Breyfogle, Norm (p), Rubinstein, Josef (i). "Metamorphosis Part Three: The Economics of The Madhouse" Anarky, vol. 1, no. 3 (July 1, 1997). New York City, NY: DC Comics.

Grant, Alan (w), Breyfogle, Norm (p), Rubinstein, Josef (i). "Metamorphosis Part Four: Fanfare for the Common Man" Anarky, vol. 1, no. 4 (August 1, 1997). New York City, NY: DC Comics. - ↑ James Redington (2005-09-20). "The Panel: Why Work In Comics?". Silverbulletcomics.com. Archived from the original on 2008-12-01. Retrieved 2007-12-15.

- ↑ Grant, Alan. Interview conducted by Cristopher Irving, November 17, 2006. Published in: Back Issue! Raleigh, North Carolina, USA: TwoMorrows Publishing. Vol. 1, No.22, p. 21. ISSN 1932-6904. June 2007.

- ↑ Best, Daniel (2003). "Norm Breyfogle @ Adelaide Comics and Books". Adelaide Comics and Books. ACAB Publishing. Archived from the original on 2008-01-31. Retrieved 2007-01-24.

- ↑ "John Paul Leon official website". Johnpaulleon.com. Retrieved 2011-01-04.

- ↑ Klein, Todd. "How I Began," Todd Klein: Lettering - Logos - Design. Retrieved July 22, 2008. Archived July 8, 2008, at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ Eliopoulos, Chris (February 18, 2004). "RIP Bill Oakley". PULSE News. Comicon.com. Archived from the original on June 5, 2011. Retrieved 2008-08-23.

- ↑ "1974 Academy of Comic Book Arts Awards". Hahnlibrary.net. Retrieved 2011-01-04.

- ↑ Miller, John Jackson (2005-06-09). "CBG Fan Awards Archives". Forums: The Knowledge Base. CBGXtra.com. Archived from the original on 2007-03-11. Retrieved 2011-05-06.

- ↑ Grant, Batman: Anarky, p. 9 – 30.

- ↑ Grant, Batman: Anarky, p. 31 – 52.

- ↑ Grant, Batman: Anarky, p. 54 – 63.

- ↑ Grant, Batman: Anarky, p. 66 – 89.

- ↑ Grant, Batman: Anarky, p. 92 – 115.

- ↑ Grant, Batman: Anarky, p. 117 – 138.

- ↑ Grant, Batman: Anarky, p. 140 – 161.

- ↑ Grant, Batman: Anarky, p. 163 – 184.

- ↑ Grant, Batman: Anarky, p. 204.

- ↑ Grant, Batman: Anarky, p. 186 – 207.

- ↑ Greg Burga (2009-01-21). "Comics you should own: Detective 3". Delenda Est Carthago. Mesa, Arizona, United States: Blogspot. Retrieved 2009-09-11. Formerly published at:Greg Burga (2006-05-22). "Comics You Should Own #17: Detective Comics #583 - 601". Comics You Should Own. PopCultureShock. Retrieved 2008-03-05.

- ↑ VerBeek, Todd. "Anarky". Beek's Books. Archived from the original on 2012-02-05. Retrieved 2007-07-24.

- ↑ James Redington (2005-09-20). "The Panel: Why Work In Comics?". Silverbulletcomics.com. Archived from the original on 2011-05-22. Retrieved 2007-12-15.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 "Line of Fire Reviews: Anarky #2". silverbulletcomicbooks.com. Comics Bulletin. 1997-04-17. Retrieved 2007-12-15.

- 1 2 3 Morrison, Matt (2000). "Anarky: Better Dead Than Read!". Fanzing.com. Archived from the original on 2007-06-13. Retrieved 2007-03-10.

- ↑ Grant, Batman: Anarky, p. 93.

- ↑ Grant, Batman: Anarky, p. 106.

- ↑ Grant, Batman: Anarky, p. 69.

- ↑ Grant, Batman: Anarky, p. 93.

- ↑ Grant, Batman: Anarky, p. 201.

- ↑ Berridge, Edward. "Alan Grant". 2000 AD Review. Archived from the original on 2008-01-11. Retrieved 2007-01-26.

- ↑ Grant, Batman: Anarky, p. 124, 130, 163, 174.

- ↑ Grant, Batman: Anarky, p. 163.

- ↑ Grant, Batman: Anarky, p. 174.

- ↑ Best, Daniel (2007-01-06). "Alan Grant & Norm Breyfogle". Adelaide Comics and Books. ACAB Publishing. Archived from the original on 2007-04-27. Retrieved 2007-05-18.

- ↑ Cooling, William (2007-04-21). "Getting The 411: Alan Grant". 411Mania.com. Archived from the original on 2005-11-13. Retrieved 2004-08-14.

- ↑ Grant, Batman: Anarky, p. 122.

- ↑ Grant, Batman: Anarky, p. 150.

- ↑ Grant, Batman: Anarky, p. 173.

- ↑ Grant, Batman: Anarky, p. 191.

- ↑ Grant, Batman: Anarky, p. 59.

- ↑ Grant, Batman: Anarky, p. 52.

- ↑ Grant, Batman: Anarky, p. 83.

- ↑ Grant, Batman: Anarky, p. 151.

- ↑ Grant, Batman: Anarky, p. 128, 143.

- ↑ Grant, Batman: Anarky, p. 181.

- ↑ Grant, Batman: Anarky, p. 134.

- Bibliography

- Grant, Alan (w), Breyfogle, Norm, Staz Johnson, John Paul Leon (p), Mitchell, Steve, Cam Smith, Ray McCarthy et al. (i). Batman: Anarky (February 2, 1999). New York, NY: DC Comics, ISBN 1-56389-437-8.

External links

- Batman: Anarky at the Grand Comics Database

- Batman: Anarky at the Comic Book DB (archived from the original)