| Sultan al-Nasir Muhammad ibn Qala'un Mosque | |

|---|---|

| |

| Religion | |

| Affiliation | Islam |

| Location | |

| Location | Cairo, Egypt |

Shown within Egypt | |

| Geographic coordinates | 30°01′45″N 31°15′39″E / 30.029151°N 31.260945°E |

| Architecture | |

| Type | mosque |

| Style | Mamluk |

| Date established | 1318 |

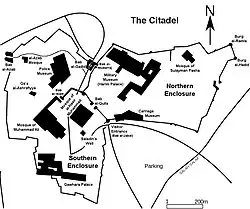

The Sultan al-Nasir Muhammad ibn Qalawun Mosque is an early 14th-century mosque at the Citadel in Cairo, Egypt. It was built by the Mamluk sultan Al-Nasr Muhammad in 1318 as the royal mosque of the Citadel, where the sultans of Cairo performed their Friday prayers. The mosque is located across the street from the courtyard access to the Mosque of Muhammad Ali. The Sultan also built a religious complex in the center of the city, next to the one by his father Qalawun.

History

Sultan al-Nasir Muhammad ibn Qalawun

Sultan al-Nasir Muhammad was one of the sons of Sultan Qalawun (d. 1290). He was reportedly short, had a lame foot, and a cataract in one eye as well. However, he still managed to rally the support of his people because he was smart and energetic. He also managed to remain on good terms with other countries. The historical chronicler Ibn Batuta says that he was of “noble character and great virtue”.[1]

Though surprisingly popular, al-Nasir did not keep control of his city throughout his life. Much of that has to do with him becoming sultan as a nine-year-old. Because the city was ripe with power mongers, his tutor, Kitbuqa sent him away to grow up and come home when he was better able to deal with the responsibility of ruling a country. Kitbuqa was killed shortly thereafter and was succeeded by a short succession of other rulers. Finally Lagin, an advisor loyal to the sultan took control and informed the young sultan he had nothing to fear and could return to Cairo.[2] Nasir was usurped one additional time during his rule. Only after being reinstated a second time did Nasir begin working on his massive construction projects.[3]

At the time, rulers of Cairo would support the city by sponsoring massive building projects which brought them prestige and created jobs. Al-Nasir’s claim to fame was building up the Citadel area that the Mamluk Empire ruled from. The Citadel resided aside from the more day-to-day people’s market place. Al-Nasir wiped out the library and audience halls of his predecessor and sponsored the building of a grand palace, aqueduct, and mosque for his own personal use in their place.[4]

The Mosque’s early days

Around 1318, when the mosque was completed, the Sultan al-Nasir used it for his daily prayer. A side room enclosed by intricate iron work served as a private place of thought for the busy sultan. The call to prayer was broadcast to the North where the palace troops would be able to hear it.[5] Perhaps unique in all of history, the funds to build this mosque exceeded its actual costs. These funds were used to buy more land and shops to support the mosque making it one of the wealthiest institutions in the city.[6]

Both the financial stability and the Sultan’s own prestige made the Citadel Mosque a desirable place to work. To decide who would get the job, the Sultan called before him all the muezzins, preachers, and readers in the city to come before him and preach. Thus, the king got to pick the best and brightest religious leaders to serve in his mosque.

The Mosque after British Conquest

When the British arrived in Cairo, the Mosque on the Citadel was well past its days of honor where it was the sultan’s choice place to meditate. When Ottomans took over Cairo they ransacked the mosque and stripped it of much of its marble paneling. Areas between the entrances grand columns were plastered to form the walls of prison cells and storage rooms.[7]

Being an amateur archeologist, Charles Moore Watson of the British army asked his commanding officer, Captain William Freeman for permission to start repairs on the mosque. Permission was granted and Watson used prisoners to tear out the plaster walls. He succeeded in clearing out the southern and eastern walls, but was afraid the northern and western walls were needed to support the roof.[7]

Mosque today

The Mosque of the Citadel is similar to how it looked in the 1300 though many repairs have been made. It is open to the public though infrequently visited by tourists. The parts of the building relying on plastered walls have been reinforced. There have also been attempts to restore the light-blue color of the ceiling.

Description

Structure

The hypostyle mosque is built as a free-standing 63 x 57 m rectangle around an inner court with a sanctuary on the qibla side and galleries surrounding the other three sides. The main entrance protrudes from the face of the western wall. There are two other entrances, on the northeastern side and on the southern side. Unlike most other mosques of Cairo, its outer walls are not paneled and have no decoration except a crenellation composed of rectangles with rounded tops. This results in a rather austere appearance which is probably accounted for by the military nature of its setting. Crenellation on the inner walls around the courtyard is of the stepped type.

There are two minarets, both built entirely of stone, one at the northeast corner and one at the northwest portal right above the main entrance; the former is the higher of the two. The top of the latter is unique in Cairo in that it has a garlic-shaped bulb. The upper structure is covered with green, white and blue glazed mosaics (faience). This style has probably been brought by a craftsman from Tabriz who is known to have come to Cairo during the reign of al-Nasir Muhammad. Contrary to all other Mamluk mosques, the base of both minarets is below the level of the roof of the mosque. This indicates that the minarets were already standing when the walls were made higher in 1335. The heightening of the walls also resulted in a row of arched windows that give the building a special character.

In the 1335 renovation, the mosque was heightened, its roof rebuilt and a dome of plastered wood covered with green tiles was added over the maqsura (prayer niche). For centuries the Qala'un Mosque was considered the most glamorous mosque in Cairo until the dome over the prayer niche collapsed in the sixteenth century and the high marble dado was carried off to Constantinople by the Ottoman conqueror Sultan Selim I. The present dome is modern, carried by granite columns taken from ancient Egyptian temples.

The Mosque of al-Nasir is also called The Mosque of the Citadel. It rests in the South Eastern part of Cairo. Though often overshadowed by mosques more central to the city, the Mosque of the Citadel (also known as the Mosque of al-Nasir) is historically significant in its own right. It was built by Sultan Nasir Mohammed ibn Kalaoun in the year 1318 (718 by the Islamic calendar). The mosque was frequently used by its sponsor as well as his military. When the Ottomans took over the city they looted it and it fell into disrepair. Its restoration began when the British took over Cairo at the end of the 18th century.

Visual aspects

The mosque in its entirety is a 206 by 186 square.[8] The mosque’s central court where praying takes place is 117 ft 6in by 76 ft 6in.[9] The ancient scholar al-Zahiri is quoted as saying “The Great Mosque of the Citadel is equally as wondrous; I am assured it can hold 5,000 faithful”.[10]

The main entrance to the mosque is a door at its north side. The south door would have been the Sultan’s private entrance, but at the time the British were taking over the eastern and southern entrance were packed with trash.[11]

A message over the doors in flowing Arabic script reads: “In the name of God the Merciful, the Gracious, He who ordered the building of this mosque, the Blessed, the Happy, for the sake of God, whose name be exalted, is our Lord and Master, the Sultan and King, the conquer of the world and faith, Nasir Mohamed, son of our Lord the Sultan Kalaoun es Saleh, in the months and year of Hijrah of the Prophet seven hundred and eighteen”.[12]

Other doors contain similar messages. The script around the building holds more religious sentiments. Lining the top of the building on the inside were glass mosaics. Nasir was the last Sultan of Cairo to use this sort of decoration extensively.[13]

The walls of the mosque were constructed using limestone pillaged by the pyramids.[14] The ten red granite pillars in the mosque were also stolen goods.[15]

Minarets

The most striking and unique feature of this mosque are its two minarets. The first is placed at the north-east corner of the Mosque where it could call troops to prayer. The other is also near the main entrance. What makes these minarets unique is their bulbous sections with finely carved decoration. Other minarets from the time are not nearly as extensively decorated.[16] Some scholars believe that Sultan al-Nasir was friendly with the Mongols at this time and may have hired a master mason from Tabriz to construct the minarets of his mosque.[17]

See also

- Bahri dynasty

- Al-Nasir Muhammad (1295 – 1341)

- Islamic architecture

References

- ↑ Lane-Poole, Stanley. The Story of Cairo. London: J. M. Dent, 1906. p 215.

- ↑ Lane-Poole, Stanley. Cairo. London: J. S. Virtue, 1898. p 89.

- ↑ Watson, C. M., and H. C. Kay. "The Mosque of Sultan Nasir Muhammad Ebn Kalaoun, in the Citadel of Cairo." Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain & Ireland 18 (1886): 477-82. p 478.

- ↑ Parker, Richard B., Robin Sabin, and Caroline Williams. Islamic Monuments in Cairo: A Practical Guide. Cairo: American University in Cairo, 1988. p 235.

- ↑ Parker, Richard B., Robin Sabin, and Caroline Williams. Islamic Monuments in Cairo: A Practical Guide. Cairo: American University in Cairo, 1988. p 239.

- ↑ Watson, C. M., and H. C. Kay. "The Mosque of Sultan Nasir Muhammad Ebn Kalaoun, in the Citadel of Cairo." Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain & Ireland 18 (1886): 477-82. p 479.

- 1 2 Watson, C. M., and H. C. Kay. "The Mosque of Sultan Nasir Muhammad Ebn Kalaoun, in the Citadel of Cairo." Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain & Ireland 18 (1886): 477-82. p 477.

- ↑ Watson, C. M., and H. C. Kay. "The Mosque of Sultan Nasir Muhammad Ebn Kalaoun, in the Citadel of Cairo." Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain & Ireland 18 (1886): 477-82. p 479

- ↑ Watson, C. M., and H. C. Kay. "The Mosque of Sultan Nasir Muhammad Ebn Kalaoun, in the Citadel of Cairo." Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain & Ireland 18 (1886): 477-82. p 482.

- ↑ Williams, John A. "Urbanization and Monument Construction in Mamluk Cairo." Muqarnas 2 (1984): 33-45. p 37.

- ↑ Watson, C. M., and H. C. Kay. "The Mosque of Sultan Nasir Muhammad Ebn Kalaoun, in the Citadel of Cairo." Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain & Ireland 18 (1886): 477-82. p 480.

- ↑ Watson, C. M., and H. C. Kay. "The Mosque of Sultan Nasir Muhammad Ebn Kalaoun, in the Citadel of Cairo." Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain & Ireland 18 (1886): 477-82. p 479

- ↑ Flood, F. B. "Umayyad Survivals and Mamluk Revivals: Qalawunid Architecture and the Great Mosque of Damascus." Muqarnas 14 (1997): 57-79. Print.p 66.

- ↑ Parker, Richard B., Robin Sabin, and Caroline Williams. Islamic Monuments in Cairo: A Practical Guide. Cairo: American University in Cairo, 1988. p 235.

- ↑ Mathews, Karen R. "The Mamluks and the Pharaohs." The Ostracon 16.1 (2004). p 235

- ↑ Lane-Poole, Stanley. Cairo. London: J. S. Virtue and, 1898. Print. Lane-Poole, Stanley. Cairo. London: J. S. Virtue and, 1898. p 86.

- ↑ Lane-Poole, Stanley. Cairo. London: J. S. Virtue and, 1898. Print.

Further reading

- Behrens-Abouseif, Doris (1989) 'Architecture of the Bahri Mamluks'. In Islamic Architecture in Cairo: An Introduction. Leiden/New York: E.J. Brill, pp. 94–132.

- Rabbat, Nasser O. (1995). The citadel of Cairo: a new interpretation of royal Mamluk architecture. Vol. 14. Leiden/New York: E.J. Brill. ISBN 90-04-10124-1.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help)

External links

- Sultan al-Nasir Muhammad ibn Qala'un Mosque at Archnet.

- Mosque of Sultan Al-Nasir Moh Smith, Martyn. "Mosque of the Citadel." Muhammad Ibn Qala'un at Eternal Egypt

- Maqrizi website page on Citadel Mosque