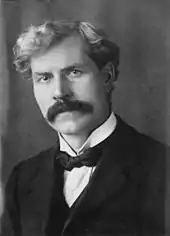

J. R. Clynes | |

|---|---|

.jpg.webp) | |

| Home Secretary | |

| In office 8 June 1929 – 26 August 1931 | |

| Prime Minister | Ramsay MacDonald |

| Preceded by | Sir William Joynson-Hicks |

| Succeeded by | Sir Herbert Samuel |

| Lord Privy Seal | |

| In office 22 January 1924 – 6 November 1924 | |

| Prime Minister | Ramsay MacDonald |

| Preceded by | Robert Cecil |

| Succeeded by | James Gascoyne-Cecil |

| Deputy Leader of the Labour Party | |

| In office 21 November 1922 – 25 October 1932 | |

| Leader |

|

| Preceded by | Office established |

| Succeeded by | Clement Attlee |

| Leader of the Labour Party | |

| In office 14 February 1921 – 21 November 1922 | |

| Chief Whip | Arthur Henderson |

| Preceded by | William Adamson |

| Succeeded by | Ramsay MacDonald |

| Minister of Food Control | |

| In office 9 July 1918 – 10 January 1919 | |

| Prime Minister | David Lloyd George |

| Preceded by | David Alfred Thomas |

| Succeeded by | George Henry Roberts |

| Parliamentary Secretary of the Ministry of Food Control | |

| In office 2 July 1917 – 9 July 1918 | |

| Prime Minister | David Lloyd George |

| Preceded by | Charles Bathurst |

| Succeeded by | Waldorf Astor |

| Member of Parliament for Manchester Platting Manchester North East (1906–1918) | |

| In office 14 November 1935 – 5 July 1945 | |

| Preceded by | Alan Chorlton |

| Succeeded by | Hugh Delargy |

| In office 8 February 1906 – 27 October 1931 | |

| Preceded by | James Fergusson |

| Succeeded by | Alan Chorlton |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 27 March 1869 Oldham, Lancashire, England |

| Died | 23 October 1949 (aged 80) London, England |

| Political party | Labour |

| Spouse |

Mary Elizabeth Harper

(m. 1893) |

| Children | 2 |

| Signature | |

John Robert Clynes (27 March 1869 – 23 October 1949)[1] was a British trade unionist and Labour Party politician. He was a Member of Parliament (MP) for 35 years, and as Leader of the Labour Party (1921–1922), led the party in its breakthrough at the 1922 general election.

He was the first Englishman to serve as leader of the Labour Party.

Early life

The son of an Irish labourer named Patrick Clynes, he was born in Oldham, Lancashire, and began working in a local cotton mill when he was ten years old.[2] Aged sixteen, he wrote a series of articles about child labour in the textile industry, and the following year he helped form the Piercers' Union. He was mainly self-educated, although he went to night school after his day's work in the mill. His first book was a dictionary and then, by careful saving of coppers, he bought a Bible, William Shakespeare's plays, and Francis Bacon's essays.[2] Later in life, he would amaze colleagues in meetings and in parliamentary debates by quoting verbatim from the Bible, Shakespeare, John Milton and John Ruskin.[3] He married Mary Elizabeth Harper, a mill worker, in 1893.

Trade union and political involvement

In 1892, Clynes became an organiser for the Lancashire Gasworkers' Union and came in contact with the Fabian Society. Having joined the Independent Labour Party, he attended the 1900 conference where the Labour Representation Committee was formed; this committee soon afterwards became the Labour Party.

Clynes stood for the new party in the 1906 general election and was elected to Parliament for Manchester North East,[1][4] becoming one of Labour's bright stars. In 1910, he became the party's deputy chairman.

Parliamentary career

During the First World War, Clynes was a supporter of British military involvement (in which he differed from Ramsay MacDonald), and, in 1917, became Parliamentary Secretary of the Ministry of Food Control in the Lloyd George coalition government. The next year, he was appointed Minister of Food Control and, at the 1918 general election, he was returned to Parliament for the Manchester Platting constituency.[5]

Clynes became leader of the party in 1921 and led it through its major breakthrough in the 1922 general election. Before that election, Labour only had fifty-two seats in Parliament but, as a result of the election, Labour's total number of seats rose to 142. He was held in considerable respect and affection in the Labour Party and, although lacking the charisma of MacDonald, was a wily operator who believed all resources available should be used to advance the material of the working classes.[6]

MacDonald had resigned as Labour leader in 1914, due to his wartime pacifism,[7] and at the 1918 general election, he lost his seat. He did not return to the House of Commons for another four years. By that stage, MacDonald's pacifism had been forgiven. When the occupant of the Labour leadership had to be decided on through a vote of Labour parliamentarians, MacDonald narrowly defeated Clynes. Clynes was a critic of government policy towards the Irish population in the years after 1918, and attacked 'a recurring system of coercion' which had left Ireland "more angry and embittered . . . than ever'[8]

Governmental office

When MacDonald became Prime Minister he made Clynes the party's leader in the Commons until the government was defeated in 1924. During the second MacDonald government of 1929–1931, Clynes served as Home Secretary.[2] In that role, Clynes gained literary prominence when he explained in the Commons his refusal to grant a visa[9] to the Russian revolutionary Leon Trotsky, then living in exile in Turkey, who had been invited by the Independent Labour Party to give a lecture in Britain. Clynes had then been immortalised by the scathing criticism of his concept of the right to asylum, voiced by Trotsky in the last chapter of his autobiography My Life, entitled "The planet without visa".[10]

In 1931, Clynes sided with Arthur Henderson and George Lansbury, against MacDonald's support for austerity measures to deal with the Great Depression. Clynes split with MacDonald when the latter left Labour to form a National Government. In the 1931 election, Clynes was one of the casualties, losing his Manchester Platting seat.[5] Nevertheless, he regained this constituency in 1935,[5] and then remained in the House of Commons until his retirement ten years later, at the 1945 general election.[5]

Retirement and death

After retiring, Clynes was living in very straitened circumstances, with no other income than trade union pension of £6 per week. This pension debarred him from the Commons Ex-Members Fund. Doctors' and nursing fees in respect of his invalid wife had hit him heavily.[11] MPs opened a fund to help and raised about £1,000.[12] Thus, after a lifetime spent in advancing the material conditions of the people, he died in relative poverty in October 1949.[6] His wife died a month later.[11]

Honours

- He was sworn in as a member of the Privy Council of the United Kingdom in 1918, giving him the honorific title "The Right Honourable" for life.

- He was awarded the Freedom of the Borough of Oldham on 9 January 1946.[13]

- He received the Honorary degree of Doctor of Civil Law (DCL) from the University of Durham and the University of Oxford.[14]

- John Clynes Court, a social housing development in Putney, south west London, is named after him.

Notes

References

- 1 2 Leigh Rayment's Historical List of MPs – Constituencies beginning with "M" (part 1)

- 1 2 3 "Mr J.R. Clynes to Leave the House". Hull Daily Mail. British Newspaper Archive. 21 May 1942. Retrieved 30 March 2016.

- ↑ Tony Judge, 'J.R. Clynes: A Political Life' (2016) Ch1

- ↑ Craig, F. W. S. (1989) [1974]. British parliamentary election results 1885–1918 (2nd ed.). Chichester: Parliamentary Research Services. p. 142. ISBN 0-900178-27-2.

- 1 2 3 4 Craig, F. W. S. (1983) [1969]. British parliamentary election results 1918–1949 (3rd ed.). Chichester: Parliamentary Research Services. p. 191. ISBN 0-900178-06-X.

- 1 2 Tony Judge, 'J.R. Clynes: A Political Life' (2016)

- ↑ Marquand, David Ramsay MacDonald, (London: Jonathan Cape 1977); ISBN 0-224-01295-9, p. 168

- ↑ Jon Lawrence 'Forging a Peaceable Kingdom: War, Violence and Fear of Brutalisation in Post-First World War Britain', JMH (2003), p.582

- ↑ "M. TROTSKY. (Hansard, 18 July 1929)". Parliamentary Debates (Hansard). 18 July 1929. Retrieved 17 August 2012.

In regard to what is called "the right of asylum," this country has the right to grant asylum to any person whom it thinks fit to admit as a political refugee. On the other hand, no alien has the right to claim admission to this country if it would be contrary to the interests of this country to receive him.

- ↑ Trotsky, Leon (1930). "Chapter 45: The Planet Without a Visa". My Life. Retrieved 17 August 2012.

The pious Mr. Clynes ought at least to have known that democracy, in a sense, inherited the right of asylum from the Christian church, which, in turn, inherited it, with much besides, from paganism. It was enough for a pursued criminal to make his way into a temple, sometimes enough even to touch only the ring of the door, to be safe from persecution. Thus the church understood the right of asylum as the right of the persecuted to an asylum, and not as an arbitrary exercise of will on the part of pagan or Christian priests.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - 1 2 "J.R. Clynes Left £9816". The Courier. Dundee: British Newspaper Archive. 7 February 1950. Retrieved 30 March 2016.

- ↑ "MR. J.R. Clynes Taken To Hospital". Hull Daily Mail. British Newspaper Archive. 31 August 1949. Retrieved 30 March 2016.

- ↑ "Honorary Freemen of the Borough".

- ↑ "John Robert Clynes".

Further reading

External links

Media related to John Robert Clynes at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to John Robert Clynes at Wikimedia Commons- Hansard 1803–2005: contributions in Parliament by J. R. Clynes

_(2022).svg.png.webp)