| V-1 and V-2 Intelligence | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of World War II technology & warfare | |||||

| |||||

| Belligerents | |||||

|

|

| ||||

| Strength | |||||

|

PR Squadrons (5 UK, 5 USA, & 4 CA)[2] agents & informants | V-1: 16 batteries of 220 men | ||||

| Part of a series on the |

Underground State |

|---|

|

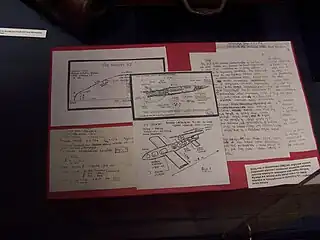

Military intelligence on the V-1 and V-2 weapons[3] developed by the Germans for attacks on the United Kingdom during the Second World War was important to countering them.: 437 Intelligence came from a number of sources and the Anglo-American intelligence agencies used it to assess the threat of the German V-weapons.

The activities included use of the Double Cross System for counter-intelligence and the British (code named) "Big Ben" project to reconstruct and evaluate German missile technology[4] for which Denmark, Poland, Luxembourg, Sweden, and the USSR provided assistance. German counter-intelligence ruses were used to mislead the Allies about V-1 launch sites and the Peenemünde Army Research Center which were targeted for attacks by the Allies.

The Polish resistance Home Army (Armia Krajowa), which conducted military operations against occupying German forces, was also heavily involved in intelligence work. This included operations investigating the German Wunderwaffe: the V-1 flying bomb and the V-2 rocket. British intelligence received their first Polish report regarding the development of these weapons at Peenemünde in 1943.[5][6]

Early reports

By the summer of 1941 Home Army intelligence began receiving reports from its field units regarding some kind of secret tests being carried out by the Germans on the island of Usedom in the Baltic Sea. A special "Bureau" was formed within intelligence group "Lombard", charged with espionage inside the 3rd Reich and the Polish areas incorporated into it after 1939, to investigate the matter and to coordinate future actions. Specialized scientific expertise was provided to the group by the engineer Antoni Kocjan, "Korona", a renowned pre-war glider constructor. Furthermore, as part of their operations the "Bureau" managed to recruit an Austrian anti-Nazi, Roman Traeger (T-As2), who was serving as an NCO in the Wehrmacht and was stationed on Usedom. Trager provided the AK with more detailed information regarding the "flying torpedoes" and pinpointed Peenemünde on Usedom as the site of the tests. The information obtained led to the first report from the AK to the British which was purportedly written by Jerzy Chmielewski, "Rafal", who was in charge of processing economic reports the "Lombard" group obtained.

Operation Most III

After V-2 flight testing began at the Blizna V-2 missile launch site (the first launch from there was on November 5, 1943), the AK had a unique opportunity to gather more information and to intercept parts of test rockets (most of which did not explode).

The AK quickly located the new testing ground at Blizna thanks to reports from local farmers and AK field units, who managed to obtain on their own pieces of the fired rockets, by arriving on the scene before German patrols. In late 1943 in cooperation with British intelligence, a plan was formed to make an attempt to capture a whole unexploded V-2 rocket and transport it to Britain.

At the time, opinion within British intelligence was divided. One group tended to believe the AK accounts and reports, while another was highly sceptical and argued that it was impossible to launch a rocket of the size reported by the AK using any known fuel. Then in early March 1944, British Intelligence Headquarters received a report of a Polish Underground worker (code name "Makary") who had crawled up to the Blizna railway line and saw on a flatcar heavily guarded by SS troops "an object which, though covered by a tarpaulin, bore every resemblance to a monstrous torpedo."[7] The Polish intelligence also informed the British about usage of liquid oxygen in a radio report from June 12, 1944. Some experts within both British and Polish intelligence communities quickly realized that learning the nature of the fuel utilized by the rockets was crucial, and hence, the need to obtain a working example.

From April 1944, numerous test rockets were falling near Sarnaki village, in the vicinity of the Bug River, south of Siemiatycze. The number of parts collected by the Polish intelligence increased. They were then analyzed by the Polish scientists in Warsaw. According to some reports, around May 20, 1944, a relatively undamaged V-2 rocket fell on the swampy bank of the Bug near Sarnaki and local Poles managed to hide it before German arrival. Subsequently, the rocket was dismantled and smuggled across Poland.[8] Operation Most III (Bridge III) secretly transported parts of the rocket out of Poland for analysis by British intelligence.

Impact on the course of the war

While the early knowledge on a rocket by AK was quite a feat in pure intelligence terms, it did not necessarily translate into significant results on the ground. On the other hand, the AK did alert the British as to the dangers posed by both missile designs, which led them to allocate more resources to bombing production and launching sites and thus lessened the eventual devastation caused by them. Also, the Operation Hydra bombing raid on Peenemünde, purportedly carried out on the basis of Home Army intelligence, did delay the V-2 by six to eight weeks.[9]

Timeline

- Key

- PR — aerial photographic reconnaissance

- exchange of early stray V2 rocket.

- exchange of early stray V2 rocket..svg.png.webp) — events regarding Nazi Germany V-weapon planning

— events regarding Nazi Germany V-weapon planning — locations in Occupied France (German: Nordfrankreich)

— locations in Occupied France (German: Nordfrankreich) — Polish reports of the Armia Krajowa

— Polish reports of the Armia Krajowa — Reports gathered by the Luxembourg Resistance

— Reports gathered by the Luxembourg Resistance ,

, .svg.png.webp) — events regarding Anglo-American intelligence

— events regarding Anglo-American intelligence ,

,  ,

,  — military operations (RAF, US, Luftwaffe)

— military operations (RAF, US, Luftwaffe)

| Date | Location/Topic | Event |

|---|---|---|

| 2 November 1939 | Oslo Report | |

| 1941 | Peenemünde | German scientist Paul Rosbaud and Norwegian XU agent Sverre Bergh submitted the first detailed description of the Peenemünde facilities and size/shape of missiles to British intelligence. Their reports were largely ignored until corroborated in 1943.[10][11] |

| 15 May 1942 | Peenemünde: P-7 | |

| 5 January 1943 | Peenemünde | |

| 19 January 1943 | Peenemünde | |

| 22 March 1943 | ||

| 22 April 1943 | Peenemünde: P-7 | |

| 1943-05 | Peenemünde | |

| 17 May 1943 | ||

| 14 May 1943 | Peenemünde: P-7 | Two sorties photographed an "unusually high level of activity" at "the Ellipse" (the Reich Director of Manpower was visiting for a V-2 test launch).: 58 |

| 4 June 1943 | Peenemünde | |

| 1943-06-12 | Peenemünde: P-7 | |

| 1943-06-22 | ||

| 1943-06-23 | Peenemünde: P-7 | |

| 1943-06-29 | Peenemünde | |

| 1943-07-26 | Peenemünde | |

| 1943-08-16 | Peenemünde | Two days prior to the Operation Hydra bombing raid on the scientists quarters, workshops, and experimental facilities, a Westland Lysander picked up French agent Lèon Faye who carried "a detailed report of the top secret V-weapon rocket development at Peenemünde" to England.[29] |

| 1943-08-22 | Denmark | An air-launched test of an overfuelled V-1 from the "G.A.F. Research Center, Karlshagen" (Peenemunde), crashed on Bornholm, and Hasager Christiansen obtained photos of the automatic pilot, compressed air cylinder, main fuselage and wings before the German recovery team arrived.[30] |

| September 1943 | Peenemünde: P-7 | PR showed P-7 bomb craters,[31] but Peenemünde personnel had fabricated post-Hydra bomb damage by creating craters in the sand, by blowing-up lightly damaged and minor buildings, and by painting "black and white lines to simulate charred beams".[32] Research and development on the V-2 continued promptly despite Operation Hydra, and the next V-2 test launch was 49 days later. |

| 1943-09-07 | ||

| 1943-09-19 | ||

| 1943-09-28 | ||

| 1943-09-30 | 133 V-weapon facilities had been photographed by the PRU[34] including V-1 flying bomb storage depots in Occupied France under construction since August.: 194 (They were not used for the modified sites.)[1] | |

| September 1943 | ||

| October 1943 | ||

| 3 October 1943 | ||

| 1943 autumn | ||

| 21 October 1943 | PR was ordered for the whole of Northern France.[40] | |

| 28 October 1943 | ||

| 3 November 1943 | ||

| 28 November 1943 | Peenemünde-West | |

| November 1943 | 72 "ski sites" had been photographed.[46]: 184 | |

| 4 December 1943 | PR was again conducted across Northern France[35]: 3 just before the December 5 start of "Crossbow Operations Against Ski Sites", which the Combined Chiefs of Staff authorized on December 2.[47] | |

| 4 December 1943 | ||

| 4 January 1944 | The Pentagon Eglin Field |

|

| February 1944 | Peenemunde: P-7 | PR showed roads north of the ellipse that matched roadways later discovered after the Normandy Invasion at the Château de Molay V-2 site. |

| 25 February 1944 | ||

| March 1944 | ||

| March 1944 | occupied Poland | |

| 22 April 1944 | ||

| 26 April 1944 | PR identified the 1st camouflaged "modified" site,[35]: 8 and 12 more were identified within days.[55] The V-1 launch site design had been modified for simplicity and to use transportable catapult sections, making them "more difficult to discover and easy to replace", bombing more difficult, and completion time relatively short when V-1 supplies were sufficient. Crossbow continued bombing the obsolete and heavily damaged "ski sites" due to a German deception that portrayed them as being repaired.[56] Additionally, espionage became more difficult as only German & prisoner/forced labor was used for "modified" sites instead of the previously-used French construction firms.[57] | |

| April 1944 | Mittelwerk | |

| 5 May 1944 | Poland | |

| 6 June 1944 | 61 modified sites had been photographed, and 83 of 96 ski sites had been destroyed (only 2 of the ski sites launched V-1s).[61] | |

| 10 June 1944 | Belgium | |

| 11 June 1944 | ||

| 11 June 1944 | 66 modified sites had been photographed. On the 13th just after midnight, the Saleux site launched the first combat V-1 (Hans Kammler visited the Saleux V-1 site on August 10).[64] | |

| 1944-06 | RAF Medmenham | |

| 13 June 1944 | Stray test V2 rocket explodes over Bäckebo Sweden, fired from Peenemünde and aimed at Baltic sea outside island of Bornholm, but overshoots the target area and lands in south Sweden. Remains are shipped to the UK . | |

| 17 June 1944 | Poland | |

| 30 June 1944 | ||

| 1944-07-16 | ||

| 1944-07-18 | ||

| July 1944 | Wright Field | |

| 21 July 1944 | ||

| 22 July 1944 | ||

| 28 July 1944 | Big Ben | |

| 31 July 1944 | ||

| 15 August 1944 | Double Cross System | |

| 25 August 1944 | ||

| 25 August 1944 | Belgium | |

| 8 September 1944 | Sound ranging | |

| 17 September 1944 | Netherlands | |

| 22 September 1944 | Poland | |

| 1944-10 | Mittelwerk | PR of Niedersachswerfen showed shadows of railcars consistent with those loaded with V-2s. |

| 25 October 1944 | Netherlands | |

| December 1944 | Royal Artillery | |

| 31 December 1944 | Netherlands | |

| 8 February 1945 | Peenemünde | |

| 20 March 1945 | Netherlands | |

| March 1945 | Operation Paperclip | A Polish laboratory technician found pieces of the Osenberg List of German scientists in a toilet at Bonn University.[95] The United States Army Ordnance Corps used the Osenberg List to compile the list of rocket scientists to be captured and interrogated (Wernher von Braun's name was at the top).[96] |

| 11 April 1945 | Mittelwerk | |

The day after Strategic Bombing Directive No. 4 ended the strategic air war in Europe, the use of radar was discontinued in the London Civil Defence Region for detecting V-2 launches. The last launches had been on March 27 (V-2) and March 29 (V-1 flying bomb).

See also

References

- Notes

- 1 2 Jones 1978, p. 423.

- ↑ Ordway & Sharpe 1979, p. 113.

- ↑ Jones 1978, p. 437.

- ↑ McGovern 1964, p. 74.

- ↑ Garliński 1978, p. 221.

- ↑ FOOTNOTE: Regarding the "widespread conviction" and Wojewódzki (pgs 18, 252) claim that :

Polish authorities in London received despatches and reports on the subject of Peenemünde as early as 1942,

the archives of the VIth Bureau that remained in Polish hands after the war and which, as of 1984, were to be found complete in the Polish Underground Movement (1939–45) Study Trust in London. Among them is "not a single document from 1942 concerning the V-1 and the V-2, nor has any been entered in the day-book of the VIth Bureau", and the lack of documentation regarding the claim was confirmed by Colonel Protasewicz and Lieutenant Colonel Bohdan Zielinski, head of the Bureau of Military Studies in the Home Army Intelligence in Warsaw 1943-44. - 1 2 McGovern 1964, p. 42.

- ↑ Wojewódzki, Michał (1984). Akcja V-1, V-2 (in Polish). Warsaw. ISBN 83-211-0521-1.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) FOOTNOTE: there are no material evidence, nor first-hand reports on capturing a whole rocket in May 1944, only several second-hand ones. An Intelligence report from June 12 mentions only parts of a rocket. - ↑ Middlebrook 1982, p. 222.

- ↑ Kramish, Arnold (1987). Griffen - den største spionhistorien. Oslo: J. W. Cappelens Forlag. ISBN 978-82-02-10743-7.

- ↑ Bergh, Sverre (2006). Spion i Hitlers Rike. Oslo: Cappelen. ISBN 978-82-04-12361-9.

- ↑ Ordway & Sharpe 1979, p. 114.

- 1 2 Aloyse Raths - Unheivolle Jahre für Luxemburg 1940-1945 p. 259-261

- ↑ Garliński 1978, p. 61.

- ↑ Jones 1978, p. 333.

- ↑ Bowman 1999, p. 16.

- ↑ Jones 1978, p. 339, 433.

- ↑ Collier 1976, p. 143.

- 1 2 Jones 1978, p. 338.

- ↑ Jones 1978, p. 337.

- ↑ Middlebrook 1982, p. 41.

- ↑ Jones 1978, p. 300c,340.

- ↑ Collier 1976, p. 18.

- ↑ Pocock, Rowland F (1967). German Guided Missiles of the Second World War. New York: Arco Publishing Company, Inc. p. 22.

- ↑ Collier, 1976

- ↑ Cooksley 1979, p. 53.

- ↑ "Constance Babington Smith". The Daily Telegraph. London. 9 August 2000. Archived from the original on 13 July 2011.

- ↑ "The V2 rocket: A romance with the future". Science in war. The Science Museum. 2004. Retrieved 2008-09-22.

- ↑ Verity, Hugh. We Landed by Moonlight. p. 118. (cited by Middlebrook p. 39)

- ↑ Jones 1978, p. 300d.

- ↑ Ordway & Sharpe 1979, p. 174e.

- ↑ Middlebrook 1982, p. 198.

- ↑ Jones 1978, p. 353.

- 1 2 3 Bowman 1999, p. 18.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "The V-Weapons". After The Battle. No. 6. 1974. pp. 3, 14, 16. Archived from the original on 2009-03-12. Retrieved 2007-12-26.

- ↑ "Michel Hollard" (in German). christianCH.ch. Retrieved 2020-01-29.

- ↑ Jones 1978, p. 300e,360.

- ↑ "Eurostar remembers Michel Hollard". 26 April 2004. Retrieved 2010-03-15.

- ↑ McKillop, January 1944

- ↑ Collier 1976, p. 36.

- ↑ Sharp, C. Martin; Bowyer, Michael J. F. (1971). Mosquito. London: Faber & Faber. p. 132. ISBN 978-0-85979-115-1.

- ↑ "Operation Crossbow - V1 Bois Carré Sites". The National Collection of Aerial Photography. Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments of Scotland. Retrieved 2011-12-26.

- ↑ Jones 1978, p. 300e.

- ↑ Jones 1978, p. 367.

- ↑ Cooksley 1979, p. 44.

- 1 2 Gurney, Gene (Major, USAF) (1962). The War in the Air: a pictorial history of World War II Air Forces in combat. New York: Bonanza Books. p. 184.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Bomber Command Campaign Diary

- ↑ Jones 1978, p. 354,374.

- 1 2 Zaloga 2008, p. 29.

- ↑ D'Olier, Franklin; Alexander; Ball; Bowman; Galbraith; Likert; McNamee; Nitze; Russell; Searls; Wright (September 30, 1945). "The Secondary Campaigns". United States Strategic Bombing Survey, Summary Report (European War). Archived from the original on 2008-05-16. Retrieved 2008-09-22. (Alternate version) (cited by Mets p. 239, which has the "three or four" numbers)

- 1 2 3 Henshall, Phillip (1985). Hitler's Rocket Sites. New York: St Martin's Press. pp. 64, 111. ISBN 978-0-312-38822-5.

- ↑ Jones 1978, p. 426.

- ↑ Dornberger, Walter (1954) [1952: V2--Der Schuss ins Weltall]. V-2. translated by James Cleugh and Geoffrey Halliday (1979 Bantam ed.). New York: Viking Press. p. 214. ISBN 978-0-553-12660-0.

- ↑ Zaloga 2008, p. 31.

- ↑ "V-Bomb Photo Search". Life Magazine: 143. October 28, 1957. Retrieved 2010-02-12.

- ↑ Zaloga 2008, p. 3.

- ↑ Zaloga

- ↑ Jones 1978, p. 454.

- ↑ Garliński 1978, pp. 52, 82.

- ↑ Jones 1978, p. 436.

- ↑ Zaloga 2008, p. 32,75.

- ↑ Jones 1978, p. 417.

- ↑ Ordway & Sharpe 1979, p. 174d.

- ↑ Ordway & Sharpe 1979, p. 258d.

- ↑ Jones 1978, p. 339.

- ↑ Collier 1976, p. 68,82,84,103.

- ↑ Cooksley 1979, p. 81.

- ↑ Mets, David R. (1997) [1988]. Master of Airpower: General Carl A. Spaatz (paperback ed.). p. 239.

- ↑ Clostermann, Pierre (2004). The Big Show. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson. ISBN 978-0-297-84619-2. Retrieved 2010-03-15.

- ↑ Jones 1978, p. 434.

- 1 2 3 4 Huzel, Dieter K (1960). Peenemünde to Canaveral. Englewood Cliffs NJ: Prentice Hall. p. 93.

- ↑ Ordway & Sharpe 1979, p. 174b.

- ↑ U.S. Air Force Tactical Missiles, (2009), George Mindling, Robert Bolton ISBN 978-0-557-00029-6

- ↑ Collier 1976, p. 103.

- ↑ Ordway & Sharpe 1979, p. 158,173.

- ↑ McGovern 1964, p. 71.

- ↑ Jones 1978, p. 444.

- ↑ Jones 1978, p. 446.

- ↑ Zaloga 2008, p. 42.

- ↑ von Braun, Wernher; Ordway III, Frederick I; Dooling, David Jr (1985) [1975]. Space Travel: A History (first ed.). New York: Harper & Row. p. 105. ISBN 978-0-06-181898-1.

- ↑ Cooksley 1979, p. 82.

- ↑ Collier, Basil (1995) [1957]. Butler, J. R. M. (ed.). The Defence of the United Kingdom. History of the Second World War. Her Majesty's Stationery Office. ISBN 978-1-870423-09-0. (cited as the "Official History" by Jones, p. 423)

- ↑ Eisenhower, David (1991) [1986]. Eisenhower: At War 1943-1945. New York: Wings Books. p. 349. ISBN 978-0-517-06501-3.

Of the 10,500 V-I's launched at England, an estimated 25 percent flew off course because of malfunction. Roughly 20 percent penetrated British defenses and hit targets, claiming 10,000 lives and 1.1 million homes

- 1 2 Gruen 1998, p. 37.

- ↑ Craven, Wesley Frank; Cate, James Lea (eds.). Volume 3 Europe: Argument to V-E Day. The Army Air Forces in World War II. p. 535. ISBN 978-1-4289-1586-2 – via Hyperwar Foundation.

- 1 2 McKillop, Combat Chronology of the US Army Air Forces August 1944

- ↑ Ordway & Sharpe 1979, p. 251.

- 1 2 Johnson, David (1982). V-1, V-2: Hitler's Vengeance on London. Stein and Day. pp. 117, 130.

- ↑ Campaign Diary September 1944

- ↑ Pocock, Rowland F (1967). German Guided Missiles of the Second World War. New York: Arco Publishing Company, Inc. p. 104.

- ↑ Zaloga 2008, p. 46.

- ↑ Cooksley 1979, p. 56, 157.

- ↑ Mikhail, Devi︠a︡taev (2015). Pobeg iz ada: Na samolete vraga iz nemet︠s︡ko-fashistskogo plena (in Russian). Moscow, Russia: Moskva : Obshchestvo sokhranenii︠a︡ literaturnogo nasledii︠a︡. ISBN 978-5-902484-72-1. LCCN 2016454013.

- ↑ Collier 1976, p. 133–6.

- ↑ McGovern 1964, p. 104.

- ↑ Ordway & Sharpe 1979, p. 314.

- ↑ Maridor, Jean. "Le site V1 de Cherbourg Brécourt". Les bombes volantes V1 (in French). Retrieved 2008-02-27.

- Bibliography

- Bowman, Martin W (1999-07-15). Mosquito Photo-Reconnaissance Units of World War 2. ISBN 978-1-85532-891-4 – via Google Books.

- Collier, Basil (1976) [1964]. The Battle of the V-Weapons, 1944-1945. Yorkshire: The Emfield Press. ISBN 978-0-7057-0070-2.

- Cooksley, Peter G (1979). Flying Bomb. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons.

- Garliński, Józef (1978). Hitler's Last Weapons: The Underground War against the V1 and V2. New York: Times Books.

- Gruen, Adam L (1998). "Preemptive Defense, Allied Air Power Versus Hitler's V-Weapons, 1943–1945". The U.S. Army Air Forces in World War II. pp. 4(Round 1), 5(Round 2). Archived from the original on 2009-07-05. Retrieved 2007-05-07.

- McGovern, James (1964). Crossbow and Overcast. New York: W. Morrow – via archive.org.

- Middlebrook, Martin (1982). The Peenemünde Raid: The Night of 17–18 August 1943. New York: Bobbs-Merrill.

- Ordway, Frederick I III; Sharpe, Mitchell R (1979). The Rocket Team. Apogee Books Space Series 36. New York: Thomas Y. Crowell. pp. 57, 114, 117, 174b–e, 251, 258d. ISBN 978-1-894959-00-1. Archived from the original (index) on 2012-03-04. Retrieved 2012-03-14.

- Jones, R. V. (1978). Most Secret War: British Scientific Intelligence 1939-1945. London: Hamish Hamilton. ISBN 978-0-241-89746-1.

- "Campaign Diary". Royal Air Force Bomber Command 60th Anniversary. UK Crown. Retrieved 2009-03-22.

- McKillop, Jack. "Combat Chronology of the USAAF". Archived from the original on 2007-06-10. Retrieved 2007-05-25.

- Zaloga, Steven J. (2008) [2007]. German V-Weapon Sites 1943-45. Fortress 72. New York: Osprey Publishing Ltd. ISBN 978-1-84603-247-9.

Further reading

- Churchill 'Memoirs of the Second World War'

- Eisenhower 'European Crusade'

- V-2 Ballistic Missile 1942 - 52