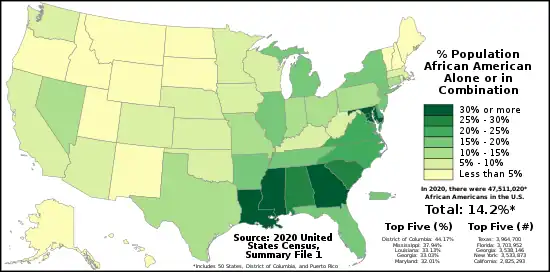

Alzheimer's disease (AD) in African Americans is becoming a rising topic of interest in AD care, support, and scientific research, as African Americans are disproportionately affected by AD. Recent research on AD has shown that there are clear disparities in the disease among racial groups,[1] with higher prevalence and incidence in African Americans than the overall average. Pathologies for Alzheimer’s also seem to manifest differently in African Americans, including with neuroinflammation markers, cognitive decline, and biomarkers. Although there are genetic risk factors for Alzheimer’s, these account for few cases in all racial groups.

There are also socioeconomic disparities—such as education, representation in clinical trials, and cost of care services—between African Americans and other racial groups that are important for the care and research of AD in African Americans.

Alzheimer's disease

Alzheimer's disease (AD) is a progressive, irreversible neurodegenerative disease and it is the leading cause of dementia.[2] According to the National Institute on Aging (NIA), AD is characterized by the intracellular aggregation of Neurofibrillary tangle (NFT), which consists of hyper-phosphorylated Tau protein, and by extracellular accumulation of amyloid beta.[3] Symptoms of AD include memory loss, cognitive decline, increased anxiety or aggression.[4] The disease can be fatal.[5]

Prevalence and incidence

In 2020, approximately 5.8 million Americans over the age of 65 (or approximately 1 in 10 people in that age group) had AD.[6] Risk for the disease increases with age, with 32% of people over the age of 85 living with AD. The number of AD patients will increase rapidly in the coming years, as the majority of the Baby Boomer generation has reached the age of 65 and the population of Americans over the age of 65 is projected to grow to 88 million by 2050.[7]

African Americans are about twice as likely to have AD as Caucasians,[8] and the prevalence of AD in African Americans is higher than that in any other racial group.[9] 21.3% of African Americans over the age of 70 have AD,[10] a much higher prevalence than the national average. The risk of dementia (not limited to AD) among relatives of African Americans who have AD is 43.7%,[8] suggesting a strong role of genetics in disease onset. The incidence of AD in African Americans is also the highest out of all racial groups. The age-adjusted incidence rate per 1,000 people per year is 26.6 for African Americans, compared to the overall average of 21.7.[11]

Neuroinflammation

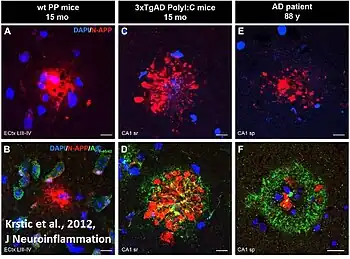

Neuroinflammation has been suggested to play a prominent role in the pathogenesis of AD due to the discovery of increased levels of inflammatory markers in AD patients and the identification of genes that are associated with innate immune functions, such as TREM2 and CD33, as AD risk genes.[12][13] The exact mechanism is still unclear, but a leading hypothesis is that neuroinflammation exacerbates amyloid beta and tau pathologies. Positron emission tomography (PET) scanning also showed increased microglia activation (inflammation) in the brains of AD patients. Microglia acts as the macrophage for the Central nervous system (CNS), and its main functions include maintenance of neuronal networks and injury repairs.[14]

There is an increased level of inflammation markers, such as IL-1β, MIG, TRAIL, and FADD, in the brains of African Americans compared to Caucasians. Furthermore, the NLPR3 inflammasome that is thought to be critically involved in AD has increased activation in African Americans.[15] Evidence also suggests a stronger association between the level of IL-8 (an inflammation marker) and cognitive performance in African Americans than Caucasians.[16]

Cognitive decline and mild cognitive impairment

Cognitive decline is a hallmark of Alzheimer's disease. Because AD involves neuropathological changes in the cortex and hippocampus, AD patients often show deficits in learning, memory, and language, and the precise nature and severity of the cognitive decline also reflects disease progression.[17]

The Alzheimer's Association defines Mild cognitive impairment (MCI) as "an early stage of memory loss or other cognitive ability loss (such as language or visual/spatial perception) in individuals who maintain the ability to independently perform most activities of daily living."[18] For AD, MCI can be an indicator of disease onset in early stages if the other hallmarks are also present. There are two types of MCI: amnestic MCI, which primarily affects the memory, and nonamnestic MCI, which affects thinking skills other than the memory.[18] The incidence of MCI is higher in African American populations compared to White populations. However, risk factors of AD, such as diabetes and cardiovascular diseases, are not associated with an increased risk of MCI in African Americans.[19] The rate of cognitive decline in MCI also appears to be faster in African Americans.[20] But the majority of African American patients with MCI are considered nonamnestic, particularly in language and executive function,[21] so diagnosis of MCI among African Americans could lead to early interventions that delay further cognitive decline.

Biomarkers

A biomarker is a measurable indicator of a disease's state and the status of the body. It is helpful in disease diagnosis, tracking progression, and monitoring the response to treatment.[22] Developing reliable biomarkers is an important part of AD research because an early, correct clinical diagnosis would allow physicians to initiate treatment with symptomatic and disease-modifying drugs.[23] Biomarkers alone cannot show if a person might have AD, as they are only part of the assessment; however, they can help physicians and researchers identify potential risk factors, detect early brain changes, and track responses to drugs and other non-pharmacological interventions.[22]

Brain imaging

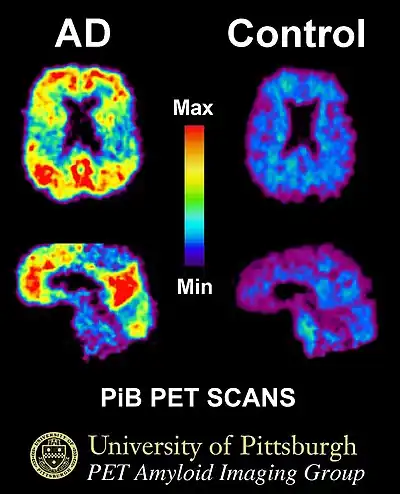

Positron emission tomography (PET) is a brain imaging technique that uses a small amount of radioactive substance, called a tracer, to measure energy use or a specific molecule in different brain regions.[22] By selecting different tracers, physicians and researchers can measure different biomarkers associated with Alzheimer's disease.

Amyloid PET measures the abnormal deposits of amyloid beta. Higher levels of amyloid beta are associated with presence of amyloid plaques, one of the hallmarks of AD.[22] The current data on amyloid PET in African Americans is inconclusive, with results suggesting that amyloid deposition could be higher or lower in African Americans compared to Whites.[24]

Tau PET detects the abnormal accumulation of tau protein, which is also a hallmark of AD. It is not commonly used in medical practice to diagnose patients,[22] but it is still useful in research settings to test potential treatments. A tau imaging study found no racial differences in tau deposition.[24]

CSF biomarkers

The cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) surrounds the brain and spinal cord to provide protection, supply nutrients, and help maintain the integrity of the blood–brain barrier.[22] Doctors can access CSF through a lumbar puncture, commonly known as the spinal tab, to diagnose AD or other types of dementia. The mostly widely used CSF biomarkers for AD are amyloid beta 42 (the major component of amyloid plaques),[22] total tau (T-tau), and phosphorylated tau (the major component of tau tangles).[22][23]

Studies have shown that although CSF amyloid beta 42 levels are similar in African American and White patients, African American patients with MCI have higher amyloid beta 40 levels than White participants with MCI. Tau CSF studies have found that tau isoforms, total-tau and p-tau181 (a form of phosphorylated tau), are lower in African American patients than White patients, suggesting lower levels of tau pathology or lower amyloid-induced tau pathology. However, CSF tau levels are not found to be associated with comorbidities such as cardiovascular diseases.[24]

Risk factors

Alzheimer's disease is a complex condition where there isn't a single cause, but some risk factors have been identified.[25] Some are unchangeable, like age and heredity, but some are environmental factors that can be modified to influence disease onset and progression.

Genetics

There are two categories of genes influencing AD: risk genes, which increase the risk of developing AD but do not guarantee that the disease will develop, and deterministic genes that actually cause AD. Fewer than 1% of AD cases are caused by deterministic genes.[25] Of the genes known to be associated with AD in non-Hispanic White patients, only a small subset of genes, including APOE and ABCA7, were implicated at a nominal significance level or stronger in African American individuals,[26] suggesting that further research on the genetics of African American AD patients is necessary to understand the disease pathologies.

APOE ε4

_(IB68).jpg.webp)

The Apolipoprotein E (APOE) is a protein involved in transportation of fats, like cholesterol, in the bloodstream. APOE comes in three different forms, or alleles: ε2, ε3, and ε4. Each person carries two APOE alleles, one from each biological parent, resulting in six possible pairs: ε2/ε2, ε2/ε3, ε2/ε4, ε3/ε3, ε3/ε4, ε4/ε4.[8] Of these, APOE ε4 is associated with increased amyloid beta accumulation[27] and early AD onset.[28][29] APOE ε4 is the strongest risk gene that has been discovered,[28] as inheriting one or two copies of the ε4 allele increases the risk of developing AD by about three times.[30]

Yet, African Americans with APOE ε4 are at a lower risk of developing AD than other racial groups,[31] even though nearly 40% of African Americans have at least one ε4 allele, compared to only 26% of European Americans.[8] Among individuals with APOE ε4 homozygosity (those that have two ε4 alleles), African Americans have significantly lower odds for developing AD, at an odds ratio (OR) of 2.2–5.7, compared to non-Hispanic Whites (OR: 14.9) and East-Asians (OR: 11.8–33.1). The same is true among individuals with APOE ε4 heterozygosity (according to a study of individuals with APOE ε3/ε4 heterozygosity): African Americans have an OR of 1.1–2.2, much lower than non-Hispanic Whites (OR: 3.2) and East-Asians (OR: 3.1–5.6).[31]

However, for individuals without the APOE ε4 allele, the cumulative risk of AD was four times higher for African Americans than Whites (risk ratio: 4.4).[32]

| Ethnic group | APOE genotype frequency (%) | APOE allele frequency (%) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ε2/ε2 | ε2/ε3 | ε3/ε3 | ε2/ε4 | ε3/ε4 | ε4/ε4 | ε2 | ε3 | ε4 | |

| Caucasians | |||||||||

| AD patients | 0.2 | 4.8 | 36.4 | 2.6 | 41.1 | 14.8 | 3.9 | 59.4 | 36.7 |

| Controls | 0.8 | 12.7 | 60.9 | 2.6 | 21.3 | 1.8 | 8.4 | 77.9 | 13.7 |

| African Americans | |||||||||

| AD patients | 1.7 | 9.8 | 36.2 | 2.1 | 37.9 | 12.3 | 7.7 | 59.1 | 32.2 |

| Controls | 0.8 | 12.9 | 50.4 | 2.1 | 31.8 | 2.1 | 8.3 | 72.7 | 19.0 |

| Ethnic group | APOE genotype | |

|---|---|---|

| ε3/ε4 | ε4/ε4 | |

| Non-Hispanic Whites | 3.2 | 14.9 |

| African Americans | 1.1-2.2 | 2.2-5.7 |

APP

The amyloid-beta precursor protein (APP) is a transmembrane protein whose proteolysis produces the amyloid beta peptides.[34] Several rare mutations on APP cause Familial Alzheimer's disease (FAD), a subset of early-onset AD (in which patients develop symptoms by their early 40s), in only a few hundred extended families worldwide. FAD accounts for fewer than 1% of all AD cases.[28]

APP is cleaved first by β-secretase and then γ-secretase to produce amyloid beta peptide. Most of the APP mutations cluster near the β-secretase and γ-secretase cleaving sites. Mutations that cluster near the β-secretase cleaving site generally increase total amyloid beta levels, while mutations that cluster near the γ-secretase cleaving sites generally increase the ratio of amyloid beta 42 to amyloid beta 40. Amyloid beta 42 is the more toxic form of amyloid beta, so an increased ratio of amyloid beta 42 to amyloid beta 40 ratio is a sign of disease progression.[35]

PS-1 and PS-2

Presenilin 1 (PS1) and Presenilin 2 (PS2) are the cleaving enzymes in the γ-secretase complex. There are close to 200 mutations on PS1 and PS2 combined that cause early-onset Alzheimer's disease, and they predominantly alter the amino acids in their transmembrane domains. These mutations increase the production of the less soluble, more toxic Aβ42.[35]

ABCA7

ABCA7 is a member of the highly conserved family of ATP-binding cassette (ABC) transporters, which use energy from ATP hydrolysis to transfer molecules from the inside to the outside of cell membranes. The ABCA7 gene is among the top ten risk genes for AD. Risk from the ABCA7 gene is the strongest for African Americans, whose risk due to the gene has an effect size approaching that of APOE.[36] Furthermore, deleterious ABCA7 alleles can cause protein loss-of-function, and these loss-of-function mutations increase risk of AD by 80% in African Americans.[37]

The mechanism of the role played by ABCA7 in AD pathogenesis remains unknown. A leading hypothesis is that ABCA7 regulates APP processing and amyloid beta clearance.[36]

Comorbidity

A wide variety of comorbid diseases are associated with AD. Cardiovascular diseases, such as stroke, atrial fibrillation, and coronary artery disease, have been seen as closely related to the development of AD at both clinical and pathological levels.[38] In addition, factors (like obesity) that increase risk for cardiovascular diseases are also associated with an increased risk for AD.[39] Rates of severe obesity are higher among African Americans (12.1%) than Hispanics (5.8%) and Whites (5.6%).[40] Cardiovascular diseases and obesity can be managed and countered through exercise, with regular exercise also reducing the risk of developing AD by 45%.[41] Exercise also has a greater positive effect in cognitive function in AD patients who are APOE ε4 carriers compared to non-carriers. Conversely, APOE ε4 carriers with a sedentary lifestyle show a greater amyloid beta deposition compared to non-carriers.[38]

Type 2 diabetes (T2D) patients have a higher risk of developing AD and Vascular dementia. Although the exact cause of this association is unclear, alterations in insulin, glucose, and amyloid metabolism may underlie the association between both diseases. Type 2 diabetes patients also have a 25%-90% increase for cognitive impairment.[38] In 2018, African Americans were twice as likely as non-Hispanic whites to die from diabetes, and African American adults are 60% more likely than non-Hispanic whites to be diagnosed with diabetes by a physician.[42] There is also a greater prevalence of risk factors related to diabetes among African Americans,[43] contributing to the higher burden of diabetes and higher risk of AD.

Treatments

There is currently no cure for AD, but there are drugs approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) to manage disease progression.[44] Treatments can be divided into either symptomatic drugs, meaning that they only affect the symptoms and not the underlying cause, or disease-modifying drugs, meaning that they could change the disease progression over time.

| Drug name | Brand name | Drug type | Drug use | Drug class and mechanism of action | Common side effects | Delivery method |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aducanumab | ADUHELM® | Disease-modifying | MCI or mild AD | Monoclonal antibody immunotherapy that removes amyloid-beta to help reduce plaques | Amyloid-related imaging abnormalities (ARIA), which could lead to fluid building up and/or bleeding in the brain. Also headache, dizziness, diarrhea, confusion.[45] | Intravenous injection |

| Donepezil | ARICEPT® | Symptomatic | Mild, moderate, and severe AD | Cholinesterase inhibitor that prevents the breakdown of acetylcholine | Nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, muscle cramps, fatigue, weight loss.[46] | Tablet |

| Memantine | NAMENDA® | Symptomatic | Moderate to severe AD | NMDA receptor antagonist that blocks the toxic effects associated with excess glutamate and regulates glutamine activation | Dizziness, headache, diarrhea, constipation, confusion.[47] | Tablet, oral solution, or extended-release capsule |

Socioeconomic disparities

Education

People with greater levels of education generally have a lower risk of developing AD, With each additional year of formal education, the odds of developing AD decrease by 12%.[8] Several factors may contribute to this. For example, continued learning allows the brain to make more flexible and efficient use of cognitive networks, or the networks of neuron-to-neuron connections known as "cognitive reserve." Building cognitive reserve also enables a person to continue carrying out day-to-day and more complex cognitive tasks despite brain damages, such as beta-amyloid and tau accumulation.[8] Additionally, a person with greater levels of education is more likely to recognize signs of AD symptoms when they first appear and consult a physician, resulting in better prevention in disease progression and better quality of life. And fewer African Americans have tertiary education degrees than the national average: the United States Census Bureau indicated that in 2021, approximately 38% of Americans held a bachelor's degree or higher, compared to 28% of African Americans.[48]

The quality of education, in addition to its quantity, could also contribute to difference in risks. In a 2012 study, the Wechsler Test of Adult Reading was used to assess the individuals' intellectual functioning and therefore estimate the quality of education. African Americans scored significantly lower than White Non-Hispanic counterparts (of similar age, sex, and years of formal education) in many different areas such as memory, attention, and language. However, when adjusted for reading level, the previously observed differences were decreased,[49] suggesting that the quality of education needs to be taken into account when assessing cognitive impairment in AD patients.

| White | Black | Asian and Pacific Islander | Hispanic | Total | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| High school graduate or more | 90.2% | 87.9% | 90.5% | 71.6% | 89.8% |

| College graduate or more | 35.2% | 25.2% | 56.5% | 18.3% | 35% |

Clinical trials

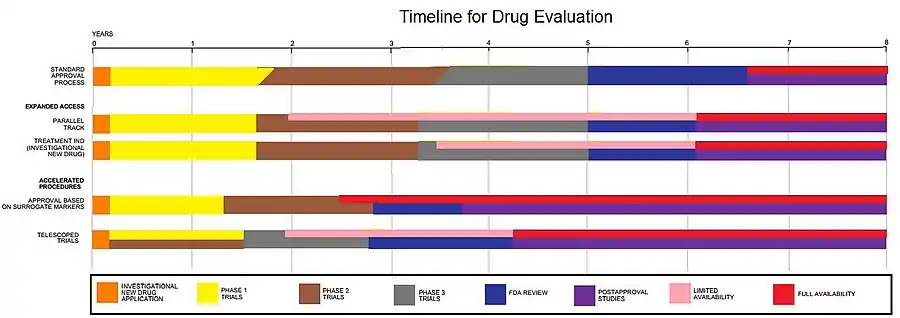

For a new drug to be approved by the Food and Drug Administration, it must first go through a clinical trial in both healthy subjects and patients. Clinical trial is important because it can determine if a new treatment is safe and efficacious enough to be distributed to patients.

African Americans are disproportionally underrepresented in clinical trials. Historically, clinical trials primarily used white males as volunteers.[50] In fact, African American patients account for only 5% of clinical trial participants in the United States.[51] This could create gaps in scientists' understanding of disease conditions, risk factors, and treatment options, especially for a disease like AD that impacts African Americans at a higher rate. More African Americans should be included in clinical trials for AD treatment so scientists and physicians could better development treatments and care plans for the African American population.

A long history of discrimination from medical professionals could be the reason why there is a high level of mistrust of clinical trials in African Americans. 62% of African Americans believe that medical research is biased against people of color.[10] Therefore, it is important to improve the diversity and inclusion of clinical trials and encourage African Americans to volunteer for clinical trials.

Cost of care services

According to 2019 data, among AD and other dementia patients, African Americans had the highest total annual payments per person, at $28,633, while White Non-Hispanics had the lowest payments, at $21,174. This difference is observed in every type of care service: the biggest difference is in hospital care, where the payments are almost $4,000 more per person annually for African Americans compared to White Non-Hispanics ($9,566 vs. $5,683).[8] The difference could be due to more co-morbidities or late-stage diagnosis, which could lead to the worsening of disease. This presents a challenge for the family and physician of African American AD patients, since the median household for African Americans is the lowest among the racial groups at $45,870.[52]

| Race/Ethnicity | Total Medicare payments per person | Hospital care | Physician care | Skilled nursing facility care | Home health care | Hospice care |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| White | $21,174 | $5,683 | $1,637 | $3,710 | $1,832 | $3,382 |

| Black/African American | $28,633 | $9,566 | $2,219 | $4,599 | $2,239 | $2,503 |

| Hispanic/Latino | $22,694 | $7,690 | $1,930 | $3,535 | $1,932 | $1,864 |

| Other | $27,548 | $8,649 | $2,171 | $3,703 | $3,969 | $2,756 |

See also

Race and health in the United States

Education of African Americans

National Institute of Aging resource page for African Americans

References

- ↑ Barnes, Lisa L. (2021-12-06). "Alzheimer disease in African American individuals: increased incidence or not enough data?". Nature Reviews Neurology. 18 (1): 56–62. doi:10.1038/s41582-021-00589-3. ISSN 1759-4766. PMC 8647782. PMID 34873310.

- ↑ "What is Alzheimer's Disease?".

- ↑ "What Happens to the Brain in Alzheimer's Disease?". National Institute on Aging. Retrieved 2022-11-18.

- ↑ "What Are the Signs of Alzheimer's Disease?". National Institute on Aging. Retrieved 2022-11-18.

- ↑ CDC (2022-09-27). "Disease of the Week - Alzheimer's Disease". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved 2022-12-05.

- ↑ Hebert, Liesi E.; Weuve, Jennifer; Scherr, Paul A.; Evans, Denis A. (2013-05-07). "Alzheimer disease in the United States (2010–2050) estimated using the 2010 census". Neurology. 80 (19): 1778–1783. doi:10.1212/WNL.0b013e31828726f5. ISSN 0028-3878. PMC 3719424. PMID 23390181.

- ↑ Bureau, US Census. "2014 National Population Projections Datasets". Census.gov. Retrieved 2022-11-17.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 "2020 Alzheimer's disease facts and figures". Alzheimer's & Dementia. 16 (3): 391–460. 2020-03-10. doi:10.1002/alz.12068. ISSN 1552-5260. PMID 32157811. S2CID 212666886.

- ↑ "CDC Newsroom". CDC. 2016-01-01. Retrieved 2022-12-05.

- 1 2 "Black Americans and Alzheimer's".

- ↑ Mayeda, Elizabeth Rose; Glymour, M Maria; Quesenberry, Charles P; Whitmer, Rachel A (2016-02-11). "Inequalities in dementia incidence between six racial and ethnic groups over 14 years". Alzheimer's & Dementia. 12 (3): 216–224. doi:10.1016/j.jalz.2015.12.007. ISSN 1552-5260. PMC 4969071. PMID 26874595.

- ↑ Leng, Fangda; Edison, Paul (2020-12-14). "Neuroinflammation and microglial activation in Alzheimer disease: where do we go from here?". Nature Reviews Neurology. 17 (3): 157–172. doi:10.1038/s41582-020-00435-y. ISSN 1759-4766. PMID 33318676. S2CID 229163795.

- ↑ Heneka, Michael T.; Carson, Monica J.; El Khoury, Joseph; Landreth, Gary E.; Brosseron, Frederik; Feinstein, Douglas L.; Jacobs, Andreas H.; Wyss-Coray, Tony; Vitorica, Javier; Ransohoff, Richard M.; Herrup, Karl; Frautschy, Sally A.; Finsen, Bente; Brown, Guy C.; Verkhratsky, Alexei (2018-04-20). "Neuroinflammation in Alzheimer's Disease". The Lancet. Neurology. 14 (4): 388–405. doi:10.1016/S1474-4422(15)70016-5. ISSN 1474-4422. PMC 5909703. PMID 25792098.

- ↑ Colonna, Marco; Butovsky, Oleg (2017-04-26). "Microglia Function in the Central Nervous System During Health and Neurodegeneration". Annual Review of Immunology. 35: 441–468. doi:10.1146/annurev-immunol-051116-052358. ISSN 0732-0582. PMC 8167938. PMID 28226226.

- ↑ Commissioner, Office of the (2020-01-06). "African Americans and Alzheimer's Disease". FDA.

- ↑ Goldstein, Felicia C.; Zhao, Liping; Steenland, Kyle; Levey, Allan I. (2015-12-17). "Inflammation and cognitive functioning in African Americans and Caucasians". International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 30 (9): 934–941. doi:10.1002/gps.4238. ISSN 0885-6230. PMC 4682666. PMID 25503371.

- ↑ Corey-Bloom, Jody (2002). "The ABC of Alzheimer's disease: cognitive changes and their management in Alzheimer's disease and related dementias". International Psychogeriatrics. 14 (Suppl 1): 51–75. doi:10.1017/s1041610203008664. ISSN 1041-6102. PMID 12636180. S2CID 1081079.

- 1 2 https://www.alz.org/alzheimers-dementia/what-is-dementia/related_conditions/mild-cognitive-impairment

- ↑ Burke, Shanna L.; Cadet, Tamara; Maddux, Marlaina (2018-07-18). "Chronic Health Illnesses as Predictors of Mild Cognitive Impairment Among African American Older Adults". Journal of the National Medical Association. 110 (4): 314–325. doi:10.1016/j.jnma.2017.06.007. ISSN 0027-9684. PMC 6108440. PMID 30126555.

- ↑ Lee, Hochang B.; Richardson, Amanda K.; Black, Betty S.; Shore, Andrew D.; Kasper, Judith D.; Rabins, Peter V. (2012). "Race and Cognitive Decline among Community-dwelling Elders with Mild Cognitive Impairment: Findings from the Memory and Medical Care Study". Aging & Mental Health. 16 (3): 372–377. doi:10.1080/13607863.2011.609533. ISSN 1360-7863. PMC 3302954. PMID 21999809.

- ↑ Gamaldo, Alyssa A.; Allaire, Jason C.; Sims, Regina C.; Whitfield, Keith E. (2010-07-01). "Assessing Mild Cognitive Impairment among Older African Americans". International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry. 25 (7): 748–755. doi:10.1002/gps.2417. ISSN 0885-6230. PMC 2889187. PMID 20069588.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 "How Biomarkers Help Diagnose Dementia". National Institute on Aging. Retrieved 2022-12-03.

- 1 2 Blennow, K.; Zetterberg, H. (2018-07-26). "Biomarkers for Alzheimer's disease: current status and prospects for the future". Journal of Internal Medicine. 284 (6): 643–663. doi:10.1111/joim.12816. PMID 30051512. S2CID 51725294.

- 1 2 3 Gleason, Carey E.; Zuelsdorff, Megan; Gooding, Diane C.; Kind, Amy J. H.; Johnson, Adrienne L.; James, Taryn T.; Lambrou, Nickolas H.; Wyman, Mary F.; Ketchum, Fred B.; Gee, Alexander; Johnson, Sterling C.; Bendlin, Barbara B.; Zetterberg, Henrik (2022). "Alzheimer's disease biomarkers in Black and non‐Hispanic White cohorts: A contextualized review of the evidence". Alzheimer's & Dementia. 18 (8): 1545–1564. doi:10.1002/alz.12511. PMC 9543531. PMID 34870885.

- 1 2 https://www.alz.org/alzheimers-dementia/what-is-alzheimers/causes-and-risk-factors

- ↑ Kunkle, Brian W.; et al. (2021). "Novel Alzheimer Disease Risk Loci and Pathways in African American Individuals Using the African Genome Resources Panel". JAMA Neurology. 78: 102. doi:10.1001/jamaneurol.2020.3536. PMC 7573798. PMID 33074286. Retrieved 2022-12-07.

- ↑ Jansen, Willemijn J.; Ossenkoppele, Rik; Knol, Dirk L.; Tijms, Betty M.; Scheltens, Philip; Verhey, Frans R. J.; Visser, Pieter Jelle (2015-05-19). "Prevalence of Cerebral Amyloid Pathology in Persons Without Dementia". JAMA. 313 (19): 1924–1938. doi:10.1001/jama.2015.4668. ISSN 0098-7484. PMC 4486209. PMID 25988462.

- 1 2 3 https://www.alz.org/alzheimers-dementia/what-is-alzheimers/causes-and-risk-factors/genetics

- ↑ "Alzheimer's Disease Genetics Fact Sheet". National Institute on Aging. Retrieved 2022-11-17.

- ↑ Holtzman, David M.; Herz, Joachim; Bu, Guojun (2012-03-02). "Apolipoprotein E and Apolipoprotein E Receptors: Normal Biology and Roles in Alzheimer Disease". Cold Spring Harbor Perspectives in Medicine. 2 (3): a006312. doi:10.1101/cshperspect.a006312. ISSN 2157-1422. PMC 3282491. PMID 22393530.

- 1 2 3 Rajabli, Farid; Feliciano, Briseida E.; Celis, Katrina; Hamilton-Nelson, Kara L.; Whitehead, Patrice L.; Adams, Larry D.; Bussies, Parker L.; Manrique, Clara P.; Rodriguez, Alejandra; Rodriguez, Vanessa; Starks, Takiyah; Byfield, Grace E.; Sierra Lopez, Carolina B.; McCauley, Jacob L.; Acosta, Heriberto (2018-12-05). "Ancestral origin of ApoE ε4 Alzheimer disease risk in Puerto Rican and African American populations". PLOS Genetics. 14 (12): e1007791. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1007791. ISSN 1553-7390. PMC 6281216. PMID 30517106.

- ↑ Tang, Ming-Xin; Stern, Yaakov; Marder, Karen; Bell, Karen; Gurland, Barry; Lantigua, Rafael; Andrews, Howard; Feng, Lin; Tycko, Benjamin; Mayeux, Richard (1998-03-11). "The APOE-∊4 Allele and the Risk of Alzheimer Disease Among African Americans, Whites, and Hispanics". JAMA. 279 (10): 751–755. doi:10.1001/jama.279.10.751. ISSN 0098-7484. PMID 9508150. S2CID 22300146.

- ↑ Farrer, Lindsay A.; Cupples, L. Adrienne; Haines, Jonathan L.; Hyman, Bradley; Kukull, Walter A.; Mayeux, Richard; Myers, Richard H.; Pericak-Vance, Margaret A.; Risch, Neil; van Duijn, Cornelia M. (1997-10-22). "Effects of Age, Sex, and Ethnicity on the Association Between Apolipoprotein E Genotype and Alzheimer Disease: A Meta-analysis". JAMA. 278 (16): 1349–1356. doi:10.1001/jama.1997.03550160069041. ISSN 0098-7484.

- ↑ "APP | ALZFORUM". www.alzforum.org. Retrieved 2022-12-04.

- 1 2 O’Brien, Richard J.; Wong, Philip C. (2011). "Amyloid Precursor Protein Processing and Alzheimer's Disease". Annual Review of Neuroscience. 34: 185–204. doi:10.1146/annurev-neuro-061010-113613. ISSN 0147-006X. PMC 3174086. PMID 21456963.

- 1 2 "ABCA7 | ALZFORUM". www.alzforum.org. Retrieved 2022-12-04.

- ↑ Dib, Shiraz; Pahnke, Jens; Gosselet, Fabien (2021-04-27). "Role of ABCA7 in Human Health and in Alzheimer's Disease". International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 22 (9): 4603. doi:10.3390/ijms22094603. ISSN 1422-0067. PMC 8124837. PMID 33925691.

- 1 2 3 Santiago, Jose A.; Potashkin, Judith A. (2021-02-12). "The Impact of Disease Comorbidities in Alzheimer's Disease". Frontiers in Aging Neuroscience. 13: 631770. doi:10.3389/fnagi.2021.631770. ISSN 1663-4365. PMC 7906983. PMID 33643025.

- ↑ "Obesity associated with a higher risk for dementia, new study finds". National Institute on Aging. 17 September 2020. Retrieved 2022-12-04.

- ↑ Carnethon, Mercedes R.; Pu, Jia; Howard, George; Albert, Michelle A.; Anderson, Cheryl A.M.; Bertoni, Alain G.; Mujahid, Mahasin S.; Palaniappan, Latha; Taylor, Herman A.; Willis, Monte; Yancy, Clyde W. (2017-11-21). "Cardiovascular Health in African Americans: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association". Circulation. 136 (21): e393–e423. doi:10.1161/CIR.0000000000000534. PMID 29061565. S2CID 22236795.

- ↑ "Physical exercise and dementia | Alzheimer's Society". www.alzheimers.org.uk. Retrieved 2022-12-04.

- ↑ "Diabetes and African Americans - The Office of Minority Health". minorityhealth.hhs.gov. Retrieved 2022-12-04.

- ↑ Barnes, Lisa L.; Bennett, David A. (2014-07-07). "Alzheimer's Disease In African Americans: Risk Factors And Challenges For The Future". Health Affairs. 33 (4): 580–586. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.2013.1353. ISSN 0278-2715. PMC 4084964. PMID 24711318.

- 1 2 "How Is Alzheimer's Disease Treated?". National Institute on Aging. Retrieved 2022-12-04.

- ↑ https://www.biogencdn.com/us/aduhelm-pi.pdf

- ↑ http://www.aricept.com/

- ↑ https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2013/021487s010s012s014,021627s008lbl.pdf

- ↑ Bureau, US Census. "Census Bureau Releases New Educational Attainment Data". Census.gov. Retrieved 2022-11-18.

- ↑ Chin, Alexander L.; Negash, Selam; Xie, Sharon; Arnold, Steven E.; Hamilton, Roy (2012-02-03). "Quality, and not just quantity, of education accounts for differences in psychometric performance between African Americans and White Non-Hispanics with Alzheimer's disease". Journal of the International Neuropsychological Society. 18 (2): 277–285. doi:10.1017/S1355617711001688. ISSN 1355-6177. PMC 3685288. PMID 22300593.

- ↑ "Diversity & Inclusion in Clinical Trials". 2022-02-07.

- ↑ "Clinical trials seek to fix their lack of racial mix". AAMC. Retrieved 2022-12-05.

- ↑ "Real Median Household Income by Race and Hispanic Origin: 1967 to 2020" (PDF).