| |||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||

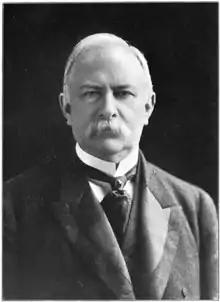

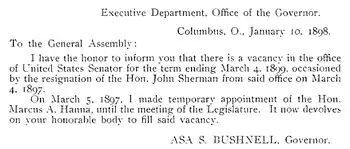

On January 12, 1898, the Ohio General Assembly met in joint convention to elect a United States Senator. The incumbent, Mark Hanna, had been appointed by Governor Asa Bushnell on March 5, 1897, to fill the vacancy caused by the resignation of John Sherman to become Secretary of State to President (and former Ohio governor) William McKinley. Hanna's appointment was only good until the legislature met and made its own choice. The legislature elected Hanna over his fellow Republican, Cleveland Mayor Robert McKisson, both for the remainder of Sherman's original term (expiring in 1899) and for a full six-year term to conclude in 1905.

Hanna, a wealthy industrialist, had successfully managed McKinley's 1896 presidential campaign. The Ohio Republican Party was bitterly divided between the faction led by McKinley, Hanna and Sherman, and one led by Ohio's other senator, Joseph B. Foraker. Bushnell was a Foraker ally, and it was only under pressure from McKinley and others that he agreed to appoint Hanna to fill Sherman's Senate seat. After Hanna gained the appointment, Republican legislators kept their majority in the November 1897 election, apparently ensuring Hanna's election once the new body met in January 1898. However, before the legislative session, the Democrats allied with a number of Republicans, mostly from the Foraker faction, hoping to take control of the legislature and defeat Hanna.

The coalition was successful in taking control of both houses of the legislature; with the Senate election to be held just over a week later, intense politicking took place. Some lawmakers went into hiding for fear they would be pressured by the other side. The coalition decided on McKisson as their candidate the day before the balloting began. Three Republican state representatives who had voted with the Democrats to organize the legislature switched sides and voted for Hanna, who triumphed with a bare majority in both the short and long term elections. Bribery was alleged; legislative leaders complained to the United States Senate, which took no action against Hanna. McKisson lost a re-election bid as mayor in 1899; Hanna remained a powerful figure in the Senate until his death in 1904.

Background and appointment of Hanna

The members of the Constitutional Convention of 1787, in drafting the Constitution, empowered state legislatures, not the people, to choose United States Senators.[1] Federal law prescribed that the senatorial election was to take place beginning on the second Tuesday after the legislature which would be in place when the senatorial term expired first met and chose officers. On the designated day, balloting for senator would take place in each of the two chambers of the legislature. If a majority of each house voted for the same candidate, then at the joint convention held the following day at noon, the candidate would be declared elected. Otherwise, there would be a roll-call vote of all legislators, with a majority of those present needed to elect. If a vacancy occurred when the legislature was not in session, the governor could make a temporary appointment to serve until lawmakers convened.[2][3]

Beginning in about 1888, there were rival factions seeking control of the Republican Party of Ohio. In 1896, one faction was led by Senator John Sherman, former governor William McKinley, and McKinley's political manager, Cleveland industrialist Mark Hanna. The other grouping was led by former governor Joseph Foraker,[4] who had the support of Ohio's current governor, Asa S. Bushnell.[5] A truce was reached for the 1896 election campaign whereby McKinley's supporters would vote for Foraker in the Ohio Legislature's January 1896 senatorial election, while Foraker would support McKinley's presidential ambitions. Foraker was elected and in June, the senator-elect placed McKinley's name in nomination at the 1896 Republican National Convention.[6] In the November election, McKinley defeated Democrat William Jennings Bryan to win the presidency; Hanna served as his campaign manager and chief fundraiser.[7] The industrialist raised millions for McKinley's campaign[8] but was bitterly attacked by Democratic newspapers for allegedly trying to buy the presidency, with McKinley as his easily dominated agent.[9] In the 1896 election, the issue of the nation's monetary standard was a major issue, with McKinley advocating the gold standard, while Bryan favored "free silver", that is, to inflate the money supply by accepting all silver presented to the government and returning the bullion to the depositor in the form of coin, even though the silver in a dollar coin was worth only about half that.[10][11]

_1896_2.jpg.webp)

After the election, McKinley offered Hanna the post of Postmaster General, which he turned down, hoping to become a senator if Sherman (whose term was to expire in 1899) was appointed to the Cabinet.[12] McKinley did not believe the rumors, which proved accurate, that the 73-year-old Sherman's mental faculties were failing, and offered him the position of Secretary of State on January 4, 1897. Sherman's acceptance meant that, once he resigned, one of Ohio's Senate seats would be in the gift of Bushnell, with the appointee to serve until the legislature reconvened in January 1898.[13][14]

Foraker was astonished when he learned that Hanna was seeking the Senate seat, not knowing that the industrialist had political ambitions. He felt that Hanna's campaign activities did not qualify him for legislative service.[15] Hanna and his allies applied considerable pressure on the governor, though initially McKinley did not participate.[16]

Bushnell did not want to appoint Hanna, and offered the seat to Congressman Theodore Burton, a member of neither faction, who turned it down. Historian Wilbur Jones speculates that the seat was refused because of Burton's unwillingness to alienate Hanna's supporters, an action which might sacrifice a career in the House of Representatives for the sake of a few months in the Senate.[17] The governor considered other options, such as arranging to get the position himself or calling a special session of the legislature and have them elect a new senator. However, Bushnell eventually decided that appointing someone else was not worth risking the wrath of the new presidential administration, and of Hanna (who was chairman of the Republican National Committee). In late February 1897, McKinley sent a personal emissary, his old friend Judge William R. Day, to Bushnell, and the governor yielded.[16][18] Hanna was given his commission by Governor Bushnell in the lobby of Washington's Arlington Hotel on the morning of March 5, 1897.[19]

Hanna's associates alleged that Bushnell had delayed the appointment of Hanna so that Foraker could be Ohio's senior senator. Herbert Croly, in his biography of Hanna, agreed,[20] and McKinley biographer H. Wayne Morgan also states that Bushnell delayed Hanna's commission for this reason.[21] Hanna biographer William Horner considers this motive possible.[19] In his memoirs, Foraker denied this, stating that Sherman had not resigned from the Senate until the afternoon of March 4, 1897 (the date on which the president and Congress were sworn in) so that Sherman could formally introduce Foraker to the Senate. Sherman, according to Foraker, was also unwilling to resign until he had been confirmed as Secretary of State, which took place on the afternoon of March 4. Foraker noted that he had been senator-elect since his selection by the legislature in January 1896 "and there was no vacancy for which Mr. Hanna could be qualified, except only that to be created by the retirement of Mr. Sherman, and Mr. Sherman refused to retire until I was sworn and in my seat".[22]

1897 state legislative campaign

Hanna obtained endorsement for election as senator by the 1897 Republican state convention during June in Toledo, and by local conventions in 84 of Ohio's 88 counties. Republicans expressed little opposition to Hanna's candidacy for senator prior to the November state elections, at which Ohioans elected a governor, other statewide officials, and a legislature.[23][24] There was much national interest in the legislative campaign, which was seen as a rematch of 1896 and a forerunner of the 1900 presidential campaign, and as a referendum on Mark Hanna. President McKinley both campaigned on Hanna's behalf in Ohio and recruited speakers for him; for the Democrats, Bryan was the leading orator.[25] Democrats hoped that by gaining a majority in the legislature and frustrating Hanna's election bid, they could claim a reversal of the voters' verdict in the 1896 presidential race, and exact revenge on the man who had helped orchestrate their defeat.[26] While the question of whether Hanna should continue in the Senate was central to the campaign, also discussed was whether McKinley's policies, including the Dingley Tariff, had brought prosperity, as well as the issue of free silver versus the gold standard.[27] The Democrats, as was their custom, did not endorse a specific candidate for Senate, but Cincinnati publisher John R. McLean was widely spoken of as the party's rival for Hanna's seat until strategists decided that his wealth and business background did not provide adequate contrast to Hanna, and McLean was forced into the background.[28]

During the campaign, William Randolph Hearst's New York Journal renewed the savage attacks on Hanna which had marked the 1896 presidential campaign; Hanna was depicted as a bloated plutocrat, frequently trampling a skull marked "Labor" and dominating a shrunken, childlike McKinley.[29] Foraker was not prominent in support of Hanna; he did endorse his junior colleague in mid-September, and made several speeches soon after the announcement, but thereafter maintained a public silence which would continue until after the vote for senator by the newly elected legislature in January 1898.[30]

Hanna made speeches across the state, much to the curiosity of Ohioans, who had heard a great deal about him for his activities on behalf of McKinley, but who did not know him well.[23] He had rarely been called upon to make public addresses. McKinley recommended his personal technique of thoroughly laying out a speech in advance, but Hanna found it did not work well for him. Instead, he preferred to compose a brief introduction and then speak extemporaneously, not always even being certain of what topics he would address. According to his biographer, Herbert Croly, the informality of Hanna's speeches won over many in his audience, and he became known as a very effective public speaker.[31] According to Philip Warken in his thesis on the 1898 Senate election, "The campaign probably worked to Hanna's advantage. The shadowy figure in the background took on shape and form, the candidate's public appearances tending to break down [Davenport's] popular but distorted image of him."[32] When Democrats attacked Hanna, who had considerable financial interests in industry, as a "labor crusher", he gave speeches inviting listeners to ask his workers whether they were well treated. Subsequently, several union leaders and workmen's committees confirmed that they had no complaint against Hanna.[33]

In the November election, 62 Republicans and 47 Democrats were elected to the Ohio House of Representatives, while in the Ohio Senate there were 18 Democrats, 17 Republicans, and 1 Independent Republican elected. This meant a majority of 15 for the Republicans on joint ballot,[34] ample, it was thought, to secure Hanna's election.[35]

Senate election

Political turmoil

The first public inkling that there might still be a serious contest for Hanna's Senate seat came the day after the November vote, when Governor Bushnell declared that the party's majority in the legislature was sufficient to elect a Republican as senator, but refrained from mentioning Hanna by name. Newspapers took note of the fact that while Bushnell had won a second term by 28,000 votes in the election, the balloting for the legislature had gone Republican by only 9,000. Soon after the election, a number of Republicans announced that they intended to ally with the Democrats and defeat Hanna.[36]

Croly lists Bushnell, Cleveland Mayor Robert McKisson, and former Republican state chairman Charles L. Kurtz as among those involved in what he called a conspiracy against Hanna.[36] Kurtz had been defeated in his re-election bid to the chairmanship by Hanna forces at the 1897 Republican state convention,[37] while McKisson had unsuccessfully sought Hanna's support in his first election run in 1895, and according to Hanna biographer William T. Horner, held a grudge as a result.[38] Hanna had also opposed his re-election in the municipal elections held in early 1897, speaking highly of McKisson's opponent to a reporter, and asking the reporter whether it was true that McKisson had secured renomination as mayor through fraud.[39] Despite poor treatment by the Hanna campaign—McKisson had been relegated to obscure rallies, except when called upon to introduce the candidate at a huge Cleveland event, and the Hanna supporters had sought to remove McKisson men from election positions—McKisson had publicly supported Hanna for senator, making several speeches on the night before election day urging Republicans to vote the straight party ticket. Nevertheless, sample ballots were sent to Cleveland voters, telling them how best to cast their ballots so as to minimize Hanna's chances, and Warken speculated that these had to come from McKisson, as the only person with motive and opportunity.[40]

Charles Dick, then Hanna's aide and later his successor as senator, recounted, "The opposition developed immediately after the election. I might say the plotting, so far as the bolters were concerned, began before the election ... The fifteen majority melted away." According to Horner, "as men elected to the Ohio legislature who were pledged to support Hanna continued to turn up opposing him ... the chances of Hanna retaining his seat began to look rather grim".[41] Kurtz disavowed the Toledo convention's endorsement of Hanna, describing the gathering as controlled by the senator's paid agents. He stated his case against Hanna: "The returns of the recent election show that he is not wanted by the party. The days of Mr. Hanna's bossism are over. The people here are against him, and that settles it."[42]

Several of the men who opposed Hanna came from Cleveland and elsewhere in Cuyahoga County, where Mayor McKisson was influential. The situation in Cincinnati's Hamilton County (home to Foraker) was complicated by the fact that the Republican legislators from there had run on a fusion ticket with the Democrats in order to defeat the local Republican bosses. These men were "Silver Republicans", as was the Independent Republican elected from Cincinnati, supporting "free silver" in opposition to McKinley, and had not pledged during the campaign to vote for Hanna if elected.[43]

Foraker was not actively involved in the controversy, and in the sole interview he gave, said he was doing his best to keep out of it. Nevertheless, most of Hanna's Republican opponents were from Foraker's wing of the party.[43] Ohio's senior senator did, however, state his belief that Hanna would have a difficult time being elected. When asked by Hanna supporters to intercede with the insurgents, Foraker responded, "I will not antagonize lifetime friends for Hanna," and that Hanna was "not honorable enough" to go to Bushnell and Kurtz and work out a solution.[44]

The new legislature convened in Columbus on Monday, January 3, 1898.[45] In the state House of Representatives, nine anti-Hanna Republicans aligned with the Democrats, electing one of the nine as Speaker. In the state Senate, an anti-Hanna Republican did not initially attend, allowing the Democrats to organize the chamber and elect one of their own as president of the body. The various legislative offices were divided between the Democrats and the insurgent Republicans.[34] Democratic forces in the Ohio Senate were boosted when the absent Republican appeared and voted with them. A margin of three in the House and two in the Senate translated into a likely margin of five against Hanna on the senatorial vote, meaning that three legislators would have to switch sides for him to retain his position.[46]

Contest in Columbus

After the combine's success in the legislature, the Hanna-controlled Republican state committee called on local activists to come to Columbus. A rally took place on the day of Governor Bushnell's second inauguration, and many in the streets booed him.[37] Much of the indignation focused on Bushnell as the only statewide official linked with the insurgents.[47] Meetings were held across the state and petitions circulated, for the most part supporting Hanna and denouncing Bushnell, Kurtz, and McKisson.[48] Croly described the scene in the days leading up to the vote for senator:

Columbus came to resemble a mediaeval city given over to an angry feud between armed partisans. Everybody was worked up to a high pitch of excitement and resentment. Blows were exchanged in the hotels and on the streets. There were threats of assassination. Timid men feared to go out after dark. Certain members of the Legislature were supplied with body-guards. Many of them never left their rooms. Detectives and spies, who were trying to track down various stories of bribery and corruption, were scattered everywhere.[49]

Hanna's forces went to great lengths to pick up the votes he needed for his election. According to Croly, they received word that state Representative John Griffith of Union County was under constant guard at the Great Southern Hotel, but was considering switching to Hanna's side. Hanna operatives aided his escape, and he was kept with his wife at Hanna headquarters at the Neil House until the vote.[50] However, Warken related that Griffith "seemed to align himself with the group that talked to him last", repeatedly changing his position and eventually supporting Hanna.[51] Hanna supporters sought to persuade other coalition Republicans to return to the fold—by one account, a Cleveland Republican tearfully refused, stating that if he voted for Hanna, McKisson would cut him off as a supplier of brick pavers to the city.[52] President McKinley did his best to help Hanna, sending a letter to one Republican whose vote was doubtful, delivered by a soldier.[41]

On January 9, newspapers printed allegations that Hanna had arranged to bribe John Otis, one of the Silver Republicans from Cincinnati. Otis alleged that he was offered $10,000 and was actually paid $1,750.[53][54] The individual said to have offered the money, a New Yorker named Henry H. Boyce, had met with Hanna adviser Estes Rathbone at least twice. Boyce denied trying to bribe Otis, though he did admit to giving a retainer payment to Otis's lawyer, and fled the state when the matter became public. Hanna denied any involvement. His opponents hoped that the incident would preface his defeat, while his supporters feared the story would prompt a public outcry. Croly and Horner agree that the allegations had little impact on public opinion.[55][56][57]

The legislative leaders had not settled on a candidate to stand against Hanna, and discussions continued until January 10, a day before the houses would vote. Democrats had tentatively agreed to vote for a Republican for senator, but were unwilling to consider a supporter of the gold standard. They considered giving a "complimentary" vote (that is, to honor the recipient) to Cincinnati publisher John R. McLean, a Democrat, before switching to a Republican. There being no requirement that the same person be elected for both the short and long Senate terms, Democrats also tried to negotiate for one of their party to be elected at least for the short term expiring in 1899. Under the latter scenario, Governor Bushnell was proposed in the long term election, but Bushnell was unwilling to support silver. At last, McKisson was decided on by the insurgents for both the short and long terms. The plan was announced on January 10, together with a statement from McKisson, which he soon disavowed: that though he would if elected remain in name a Republican, he would support the 1896 pro-silver "Chicago Platform" of Bryan and his Democrats.[58][59]

Ultimately, the contest came down to the votes of two Cincinnati Silver Republicans. The Hanna campaign at last secured the votes of both men; Croly related that one of them, Charles F. Droste, had initially sought to advance the candidacy of a free silver Republican, Col. Jeptha Garrard of Cincinnati, and when it was clear that no one else supported Garrard, agreed to give Hanna his vote.[60][61] Warken deemed the combine's failure to support Garrard "the greatest blunder of the anti-Hanna coalition. If they had pushed the Colonel's candidacy they might have secured the support of the free silver men among the Cincinnati fusionists".[61] After the vote, McKisson rejected such criticisms: the combine would never have held together to vote for a silver-supporting candidate.[61] A contemporary account calls the men's decision to support Hanna "unexplained", and that "each of these Cincinnati members had been offered the Senatorship if he would withdraw from Mr. Hanna. Whether this offer could have been made good or not is doubtful".[54]

The balloting in the separate chambers of the legislature took place on January 11, 1898. In the Ohio House, Hanna received 56 votes to 49 for McKisson, with Columbus Congressman John J. Lentz, state Representative Aquila Wiley and former congressman Adoniram J. Warner receiving one each. The vote was the same for the short and the long term.[62] Hanna's 56 votes were all from Republicans; McKisson received the ballots of 43 Democrats and six Republicans.[34] The other three votes were cast by Democrats unwilling to support a Republican.[53] One Democratic representative was absent due to illness on both days of the voting. In the Senate, there were identical votes for short and long term. McKisson received the votes of 18 Democrats and one Republican, while Hanna won the vote of 16 Republicans and the one Independent Republican. [34] The split between the two houses meant that there would be a roll-call vote of the two houses in joint convention the following day. Nevertheless, if Hanna held all 73 votes cast for him, he would be elected.[53]

According to Alfred Henry Lewis of Hearst's Journal, writing on January 12, "The opposition to Hanna was utterly disorganized by the history of yesterday, and practically speaking, went into joint session today somewhat like a routed army might take up some battle it could not avoid."[63] The 73 men pledged to Hanna went to the State House together under the protection of Hanna adherents. Croly related: "Armed guards were stationed at every important point. The State House was filled with desperate and determined men."[53] In the joint convention, held in the House Chamber, the journals of the two houses were read, detailing the tallies from the previous day. The clerks of the two houses then called the rolls. The only votes to change were those which had gone to Warner and Wiley; both were switched to McKisson.[64] Representative Aquila Wiley was the last person to vote; with Hanna having already received the 73 ballots he needed for election, Wiley maintained his vote for Lentz. The final tally, both for the short and long term was Hanna 73, McKisson 70, and Lentz 1.[54] Before the joint convention adjourned, Hanna appeared before it, thanking the legislators for his election. He stated, "I doubly thank you because under the circumstances it comes to me as an assurance of your confidence".[65]

Aftermath

Newspaper reaction to the result was generally along partisan lines. The Cincinnati Commercial Tribune, a Republican paper, stated of Hanna, "And this is the man against whom has been waged a war than which political history furnishes none more venomous, vicious, and relentlessly vituperative. It is a disgraceful story, known of all men."[66] The Blade, another Republican paper, agreed, writing, "The fight against Mr. Hanna was the most malignantly traitorous contest ever waged in the political annals of Ohio."[66] The Cincinnati Enquirer, a Silver Democratic paper, argued, "The Republican contingent which stuck to the last against Hanna has made a record which the victorious faction might well envy ... Their fight was ... against the chairman of the national committee and all its forces and resources; against the president of the United States, with his tremendous party influence and more influential patronage. Against all this they have cut down the man who a year ago was, next to the president, the leading Republican of the United States, to a pitiful majority of one in his ambition to be elected to the Senate, and that obtained under circumstances not creditable to him. They chased him so hard that he dare not stop to have the gravest charges investigated."[66] Hearst's New York Journal noted, "And so it is to be 'Senator Hanna' for seven years. Well, the senatorship can add nothing to its holder's power for evil. As long as Hanna has his money he can control senatorships, whether he occupies them or not. Perhaps it is best to have him in the open."[66]

McKisson "had recognized that to lose the fight meant political death".[67] In June 1898, McKisson and his Cuyahoga County delegation were excluded from the Republican state convention in favor of a Hanna-backed delegation. Hanna forces had lost at the county level, but, alleging irregularities, had met and sent a rival delegation.[68] McKisson ran for a third term as mayor in 1899. He survived a bitter battle in the Republican primary, but was defeated in the general election, leading to a decade of dominance by the Democrats in Cleveland.[69] McKisson returned to his career as an attorney, continuing to practice law in Cleveland until his death in 1915 at age 52.[70]

Both houses of the legislature voted to form committees to investigate alleged bribery in the result, though most Republicans abstained from voting on the resolutions. The House committee investigation ended inconclusively.[34] The Ohio Senate committee declined to allow Hanna's attorney to participate in the proceedings. Relying on legal advice, Hanna refused to testify and asked supporters not to cooperate. The state Senate committee reported that an attempt to bribe Otis had been made by an unknown agent of Hanna; three Hanna aides, including Charles Dick, were implicated.[71] The report was sent to the US Senate in May 1898, which referred it to the Committee on Privileges and Elections. The Republican majority of the committee reported in February 1899 that while it accepted that an attempt had been made to bribe Otis, the matter had been known before the vote, Otis had voted for McKisson anyway, and that there was no evidence linking Hanna to the attempt. The report did mildly admonish Hanna and his associates for not cooperating with the Ohio Senate committee. Democrats on the Privileges and Elections Committee urged further investigation, but the US Senate ordered the committee's report to be printed, and took no further action. Hanna remained a power in the Senate until his death in 1904.[72]

The extent to which money or patronage affected the outcome of the election is unclear. Congressman Burton stated, "I never saw any evidence of the use of money in Columbus and don't believe that any money was used corruptly."[73] In an interview after Hanna's death, James Rudolph Garfield, son of the late president and floor leader of the Hanna forces in the Ohio Senate, recalled that the senator "had been asked to shut his eyes to some things. But he declined to do it."[74] However, Garfield also noted, "I have never been sure as to what some of the men who called themselves Senator Hanna's friends really did do."[75] Croly believed that Hanna did not personally authorize bribes of legislators, but concedes that Hanna's supporters "may have been willing to spend money in Mr. Hanna's interest and without his knowledge."[76] The biographer suggested, "If Mr. Hanna had himself planned to purchase the vote of John C. Otis, it is reasonable to believe that the business would have been better managed."[77] Horner believes it impossible to ascertain if corruption took place, but if Hanna bribed legislators, it was because it was a common practice on both sides.[78] He notes of Hanna, "his career as a senator continued, but accusations of wrongdoing remain a part of his legacy well over a century later."[79] Public dismay at what was seen as a corrupt means of choosing federal lawmakers was a major factor in the ratification of the Seventeenth Amendment to the United States Constitution in 1913, which took the privilege of electing senators out of state legislators' hands and gave it to the people.[80]

See also

References

Citations

- ↑ Bybee, p. 510.

- ↑ Willoughby, pp. 557–559.

- ↑ Election laws.

- ↑ Horner, pp. 75–77, 82.

- ↑ Horner, p. 216.

- ↑ Stanley Jones, pp. 108–110.

- ↑ Morgan, pp. 174, 186.

- ↑ Horner, pp. 193–204.

- ↑ Horner, p. 127.

- ↑ Phillips, pp. 48–52.

- ↑ Williams, pp. 35–39.

- ↑ Leech, pp. 99–100.

- ↑ Rhodes, p. 31.

- ↑ Horner, pp. 218–221.

- ↑ Walters, pp. 132–133.

- 1 2 Morgan, p. 192.

- ↑ Wilbur Jones, pp. 10–12.

- ↑ Leech, pp. 100–101.

- 1 2 Horner, p. 219.

- ↑ Croly, pp. 240–241.

- ↑ Morgan, pp. 192–193.

- ↑ Foraker, pp. 505–506.

- 1 2 Horner, p. 221.

- ↑ Warken, pp. 18, 48.

- ↑ Horner, pp. 221–222.

- ↑ Croly, pp. 248–249.

- ↑ Warken, pp. 22–23.

- ↑ Warken, pp. 40–41.

- ↑ Horner, pp. 110–113, 220, 226.

- ↑ Walters, p. 139.

- ↑ Croly, pp. 244–247.

- ↑ Warken, p. 22.

- ↑ Wolff, pp. 146–147.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Appletons, p. 606.

- ↑ Croly, p. 250.

- 1 2 Croly, pp. 250–252.

- 1 2 Outlook 1-15-1898.

- ↑ Horner, pp. 223–224.

- ↑ Warken, pp. 12–13.

- ↑ Warken, pp. 31–34.

- 1 2 Horner, p. 230.

- ↑ Free Lance 11-13-1897.

- 1 2 Croly, pp. 252–254.

- ↑ Walters, pp. 139–140.

- ↑ Legislature, p. 3.

- ↑ Croly, p. 254.

- ↑ Warken, p. 67.

- ↑ Warken, pp. 63–64.

- ↑ Croly, p. 256.

- ↑ Croly, p. 257.

- ↑ Warken, pp. 75–76.

- ↑ Horner, pp. 225–226.

- 1 2 3 4 Croly, p. 259.

- 1 2 3 Outlook 1-22-1898.

- ↑ Croly, pp. 259–262.

- ↑ Horner, p. 227.

- ↑ Warken, p. 94.

- ↑ Croly, p. 255.

- ↑ Gould, p. 11.

- ↑ Croly, pp. 258–259.

- 1 2 3 Warken, p. 52.

- ↑ Legislature, pp. 36–37.

- ↑ Horner, p. 231, quoting Lewis 1898, p. 1.

- ↑ Legislature, pp. 37–39.

- ↑ Legislature, p. 42.

- 1 2 3 4 Public Opinion 1-20-1898.

- ↑ Warken, p. 81.

- ↑ The Public 6-25-1898.

- ↑ Croly, p. 294.

- ↑ Encyclopedia of Cleveland History.

- ↑ Croly, p. 460.

- ↑ Hanna case.

- ↑ Horner, p. 228.

- ↑ Horner, p. 229.

- ↑ Horner, pp. 229–230.

- ↑ Croly, p. 264.

- ↑ Croly, pp. 263–264.

- ↑ Horner, pp. 228–229.

- ↑ Horner, p. 233.

- ↑ Bybee, pp. 538–540.

Bibliography

Books

- Croly, Herbert (1912). Marcus Alonzo Hanna: His Life and Work. New York: The Macmillan Company. OCLC 715683.

- Foraker, Joseph Benson (1917). Notes of a Busy Life. Vol. 1. Cincinnati: Stewart & Kidd Company.

- Gould, Lewis L. (1980). The Presidency of William McKinley. American Presidency. Lawrence, Kan.: University Press of Kansas. ISBN 978-0-7006-0206-3.

- Horner, William T. (2010). Ohio's Kingmaker: Mark Hanna, Man and Myth. Athens, Ohio: Ohio University Press. ISBN 978-0-8214-1894-9.

- Jones, Stanley L. (1964). The Presidential Election of 1896. Madison, Wis.: University of Wisconsin Press. OCLC 445683.

- Leech, Margaret (1959). In the Days of McKinley. New York: Harper and Brothers. OCLC 456809.

- Morgan, H. Wayne (2003). William McKinley and His America (revised ed.). Kent, Ohio: The Kent State University Press. ISBN 978-0-87338-765-1.

- Phillips, Kevin (2003). William McKinley. New York: Times Books. ISBN 978-0-8050-6953-2.

- Rhodes, James Ford (1922). The McKinley and Roosevelt Administrations, 1897–1909. New York: The Macmillan Company. OCLC 457006.

- Walters, Everett (1948). Joseph Benson Foraker: An Uncompromising Republican. Columbus, Ohio: The Ohio History Press.

- Williams, R. Hal (2010). Realigning America: McKinley, Bryan and the Remarkable Election of 1896. Lawrence, Kan.: University Press of Kansas. ISBN 978-0-7006-1721-0.

- Willoughby, Westel Woodbury (1910). The Constitutional Law of the United States. Vol. 1. New York: Baker, Voorhis & Company.

- Appletons' Annual Cyclopaedia and Register of Important Events. Vol. 3. New York: D. Appleton and Company. 1899.

- Journal of the [Ohio] House of Representatives. Norwalk, Ohio: The Laning Printing Company. 1898.

Other sources

- Bybee, Jay S. (Winter 1997). "Ulysses at the Mast: Democracy, Federalism, and the Sirens' Song of the Seventeenth Amendment". Northwestern University Law Review. Evanston, Ill.: Northwestern University. 91 (2): 500–572. Retrieved July 24, 2012.

- Jones, Wilbur Devereux (January 1957). "Marcus A. Hanna and Theodore F. Burton". Ohio State Archaeological and Historical Quarterly. Columbus, Ohio: Ohio Historical Society. 60 (1): 10–19. Archived from the original on January 11, 2004. Retrieved July 24, 2012.

- Lewis, Alfred Henry (January 13, 1898). "Hanna senator for another seven years". New York Journal. p. 1.

- Warken, Philip W. (1960). The First Election of Marcus A. Hanna to the United States Senate (Thesis). Columbus, Ohio: The Ohio State University.

- Wolff, Gerald W. (Summer–Autumn 1970). "Mark Hanna's goal: American harmony". Ohio History. Columbus, Ohio: Ohio Historical Society. 79 (3 and 4): 138–151.

- "McKisson, Robert Erastus". Encyclopedia of Cleveland History. Cleveland: Case Western Reserve University. Retrieved July 24, 2012.

- "Is Hanna to be retired?". The Free Lance (Fredericksburg, Va.). November 13, 1897. p. 2. Retrieved July 24, 2012.

- "The Ohio Imbroglio". The Outlook. New York: The Outlook Company. 58 (3): 160–161. January 15, 1898. Retrieved July 24, 2012.

- "The Week". The Outlook. New York: The Outlook Company. 58 (4): 208–209. January 22, 1898. Retrieved July 24, 2012.

- "News". The Public. Chicago: The Public Publishing Company. 1 (12): 9–10. June 25, 1898. Retrieved July 24, 2012.

- "Mr. Hanna's election to the Senate". Public Opinion. New York: The Public Opinion Company. 24 (3): 69–71. January 20, 1898. Retrieved July 24, 2012.

- "The Election case of Marcus A. Hanna of Ohio (1899)". United States Senate. Retrieved July 24, 2012.

- "Election laws". United States Senate. Retrieved July 24, 2012.